Mathew Brady facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mathew Brady

|

|

|---|---|

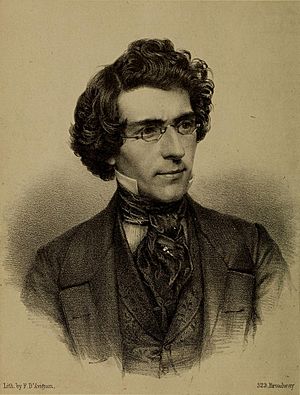

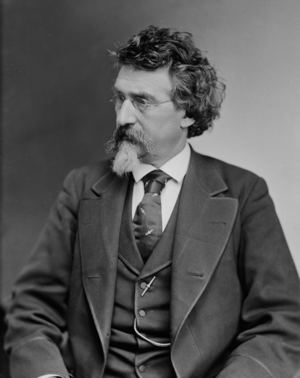

Brady c. 1875

|

|

| Born | c. 1822–1824 Warren County, New York, U.S.

|

| Died | January 15, 1896 (aged 71–74) New York City, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Congressional Cemetery |

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Juliet Handy

(m. 1850; died 1887) |

| Signature | |

Mathew B. Brady (born around 1822–1824 – died January 15, 1896) was one of the very first photographers in American history. He is most famous for his pictures of the Civil War. Brady learned photography from Samuel Morse, who helped bring the daguerreotype (an early type of photo) to America.

Brady opened his own photo studio in New York City in 1844. He took pictures of important people like John Quincy Adams and Abraham Lincoln. When the Civil War began, Brady used a special mobile studio. This allowed him to take amazing photos right on the battlefields. These pictures showed people at home what war was really like.

Thousands of war scenes were photographed. He also captured portraits of generals and politicians from both sides of the war. However, most of these photos were taken by his assistants, not by Brady himself. After the war, people lost interest in these war photos. The government also did not buy his collection as he had hoped. Brady's money problems grew, and he sadly died in debt.

Contents

Early Life and Photography Beginnings

Mathew Brady did not write much about his early life. He told reporters later in life that he was born between 1822 and 1824. His birthplace was near Lake George, New York in Warren County, New York. He was the youngest of three children. His parents, Andrew and Samantha Julia Brady, were immigrants from Ireland.

When he was about 16, Brady moved to Saratoga, New York. There, he met a portrait painter named William Page and became his student. In 1839, Brady traveled to Albany, New York, and then to New York City. He continued to study painting with Page and also with Page's former teacher, Samuel F. B. Morse.

Morse had just met Louis Jacques Daguerre in France in 1839. Daguerre had invented a new way to capture images called the daguerreotype. Morse was very excited about this new invention. At first, Brady helped by making leather cases for daguerreotypes. But soon, he became very interested in photography himself. Morse opened a studio and taught classes, and Brady was one of his first students.

Brady's Photography Career

In 1844, Brady opened his first photography studio in New York City. By 1845, he started showing off his portraits of famous Americans. These included Senator Daniel Webster and the writer Edgar Allan Poe. In 1849, he opened another studio in Washington, D.C. There, he met Juliet Handy, who everyone called 'Julia'. They got married in 1850 and lived on Staten Island.

Brady's first photos were daguerreotypes, and he won many awards for them. In the 1850s, a new type of photo called an ambrotype became popular. After that came the albumen print. This was a paper photograph made from large glass negatives. Albumen prints were most often used for photos during the American Civil War.

In 1850, Brady created The Gallery of Illustrious Americans. This was a collection of portraits of important people of his time. The collection included a famous picture of an older Andrew Jackson. While it didn't make him rich, it brought more attention to Brady's artistic work. In 1854, a photographer from Paris, André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, made carte de visite photos popular. These were small pictures, about the size of a visiting card. They quickly became a popular new item, and thousands were made and sold in the U.S. and Europe.

In 1856, Brady placed an advertisement in the New York Herald newspaper. He offered to make "photographs, ambrotypes and daguerreotypes." This ad was special because it used different styles of letters (called typeface and fonts). This was a new and creative way to advertise in the U.S.

Documenting the Civil War

When the Civil War began, Brady's business first saw a rise in sales. Soldiers leaving for war bought cartes de visite to send to their families. Brady even ran an ad telling parents to get their young soldiers' pictures before it was "too late." However, Brady soon had a bigger idea: he wanted to photograph the war itself.

He first asked his old friend, General Winfield Scott, for permission to send his photographers to battle sites. Eventually, he asked President Lincoln himself. Lincoln agreed in 1861, but Brady had to pay for the whole project himself.

Brady's efforts to photograph the American Civil War on a large scale made him famous. He brought his photo studio right onto the battlefields. Even though it was dangerous and expensive, Brady said, "I had to go. A spirit in my feet said 'Go,' and I went." His first popular war photos were from the First Battle of Bull Run. He got so close to the fighting that he almost got captured. While most photos were taken after battles, Brady was under fire at Bull Run, Petersburg, and Fredericksburg.

Brady hired many assistants, including Alexander Gardner and Timothy H. O'Sullivan. Each assistant was given a traveling darkroom. They went out to photograph scenes from the Civil War. Brady usually stayed in Washington, D.C. He organized his assistants and rarely visited battlefields himself. However, he was the main director of the project. He chose the scenes to be photographed, which was very important.

Brady's eyesight started to get worse in the 1850s. Because of this, many photos in Brady's collection were actually taken by his assistants. Brady was sometimes criticized for not saying who took each picture. It's hard to know who took a specific photo, or exactly when or where it was taken.

In October 1862, Brady opened an exhibit of photos from the Battle of Antietam in his New York gallery. It was called The Dead of Antietam. Many of these pictures showed dead bodies, which was new and shocking for Americans to see. This was the first time many Americans saw the true horrors of war in photographs. Before this, they only saw artists' drawings.

Mathew Brady and his many assistants took thousands of photos of the Civil War. Much of what we know about the Civil War comes from these pictures. Thousands of photos by Brady and his team are kept in the U.S. National Archives and the Library of Congress. These photos include Lincoln, Grant, and soldiers in camps and on battlefields. They help us understand the history of the American Civil War. Brady could not photograph actual battle scenes. The camera equipment back then needed subjects to be still for a clear photo.

After the war, people were tired of seeing war photos. Brady's popularity and business dropped sharply.

Later Years and Legacy

During the war, Brady spent over $100,000 (which is like $1.8 million today) to create more than 10,000 photo plates. He thought the U.S. government would buy his photos after the war. But the government refused, so he had to sell his New York City studio and went bankrupt. In 1875, Congress gave Brady $25,000, but he was still deeply in debt. People didn't want to remember the terrible war, so few private collectors bought his photos.

Brady became sad because of his money problems and losing his eyesight. He was also very sad when his wife died in 1887. He died without money in a hospital in New York City on January 15, 1896. He had problems after a streetcar accident. Veterans from the 7th New York Infantry paid for Brady's funeral. He was buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

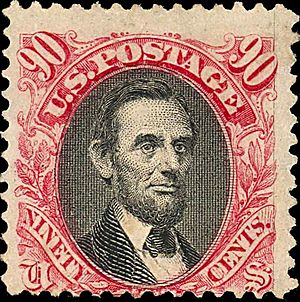

Brady photographed 18 of the 19 American presidents from John Quincy Adams to William McKinley. The only president he didn't photograph was William Henry Harrison. Harrison died in office three years before Brady started his photo collection. Brady took many pictures of Abraham Lincoln. His Lincoln photos have been used on the $5 bill and the Lincoln penny. One of his Lincoln photos was even used for a 90-cent postage stamp in 1869.

The thousands of photos taken by Mathew Brady's photographers, like Alexander Gardner and Timothy O'Sullivan, are very important. They are the most important visual record of the Civil War. They have helped historians and people today understand that time much better.

Brady photographed many important officers from the Union side of the war. These included:

- Ulysses S. Grant

- Nathaniel Banks

- Don Carlos Buell

- Ambrose Burnside

- Benjamin Butler

- Joshua Chamberlain

- George Custer

- David Farragut

- John Gibbon

- Winfield Hancock

- Samuel P. Heintzelman

- Joseph Hooker

- Oliver Otis Howard

- David Hunter

- John A. Logan

- Irvin McDowell

- George McClellan

- Freeman McGilvery

- James McPherson

- George Meade

- Montgomery C. Meigs

- David Dixon Porter

- William Rosecrans

- John Schofield

- William Sherman

- Daniel Sickles

- Henry Warner Slocum

- George Stoneman

- Edwin V. Sumner

- George Thomas

- Emory Upton

- James Wadsworth

- Lew Wallace

From the Confederate side, Brady photographed leaders like Jefferson Davis, P. G. T. Beauregard, Stonewall Jackson, and Robert E. Lee. He also photographed Lord Lyons, who was the British ambassador to Washington during the Civil War.

Photojournalism and Special Recognition

Mathew Brady is often called the father of photojournalism. This means he was a pioneer in using photos to tell news stories. He also started the idea of a "corporate credit line." This meant every photo from his studio was labeled "Photo by Brady." However, Brady only worked directly with the most important people. Most of the photo sessions were done by his assistants.

Brady was perhaps the most famous U.S. photographer in the 1800s. His name became linked to special tables used by portrait photographers. These "Brady stands" were heavy tables with an adjustable pole. They were used as armrests for people posing. They could also be extended with a neck rest to help people stay still during the long exposure times of early photography. While the name "Brady stand" is common, there's no proof that Brady himself invented it.

In 2013, a street in Tulsa, Oklahoma, called Brady Street, was officially renamed "Mathew Brady Street." The street was originally named after W. Tate Brady, a businessman who had ties to racist groups. After much discussion, the City Council of Tulsa decided to keep the name Brady for the street. But they changed it to honor Mathew B. Brady instead. Mathew Brady himself never visited Tulsa.

In 1968, Brady was added to the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum.

Books and Documentaries

Brady and his studio created over 7,000 pictures. Most of these had two negatives each. One set of these negatives eventually ended up with the U.S. government. Brady's own negatives went to a company called E. & H. T. Anthony & Company in New York in the 1870s. This happened because Brady couldn't pay for his photography supplies.

These negatives were moved around for 10 years until John C. Taylor found them in an attic and bought them. They became a key part of the Ordway–Rand collection. In 1895, Brady himself didn't know what had happened to them. Many were broken, lost, or destroyed by fire. After being owned by different people, they were found and valued by Edward Bailey Eaton. This led to them becoming the main part of a collection of Civil War photos published in 1912. This collection was called The Photographic History of the Civil War.

Some lost images are mentioned in the last episode of Ken Burns' 1990 documentary about the Civil War. Burns said that glass plate negatives were often sold to gardeners. They didn't want the images, but the glass itself to use in greenhouses. Over the years, the sun slowly faded the images, and they were lost.

However, the idea that many Civil War negatives were lost in greenhouses is likely a myth. Civil War photo historian Bob Zeller has also said this is not true. Most histories of Civil War photography don't mention that many photos were taken in 3-D. Many were published as side-by-side 3D images. Zeller's book, The Civil War in Depth, shows many of these images as they were meant to be seen, in 3-D. Mathew Brady's photographers created many Civil War images, and most were in 3-D.

Exhibitions

On September 19, 1862, two days after the Battle of Antietam, Mathew Brady sent photographer Alexander Gardner and his assistant James Gibson to take photos. The Battle of Antietam was the bloodiest single day of fighting on U.S. soil. More than 23,000 people were killed, wounded, or missing.

In October 1862, Brady showed Gardner's photos at his New York gallery. The exhibit was called "The Dead of Antietam." The New York Times newspaper wrote a review about it.

In October 2012, the National Museum of Civil War Medicine displayed 21 original Mathew Brady photographs from 1862. These photos documented the Civil War's Battle of Antietam.

Images for kids

-

Thomas Nast cartoon of Mathew Brady at "work"

-

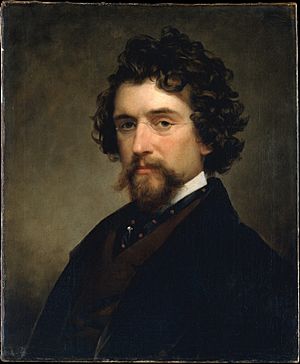

General William J. Worth; a related picture also by Brady can be found on the George Eastman House Collection website.

-

Photo of John Quincy Adams between 1843 and 1848 by Brady

-

Photo of Abraham Lincoln by Brady on the day of Lincoln's Cooper Union speech 1860

-

Photo of William McKinley by Brady 1865

-

Brady (center, wearing straw hat), with General Ambrose Burnside (reading newspaper), taken in May 1864 (See Frassanito "Grant and Lee The Virginia Campaigns")

See also

In Spanish: Mathew B. Brady para niños

In Spanish: Mathew B. Brady para niños

- 359 Broadway – Brady's studio in New York city (1853–1859)

- Photographers of the American Civil War

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |