First Battle of Bull Run facts for kids

Quick facts for kids First Battle of Bull RunBattle of First Manassas |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

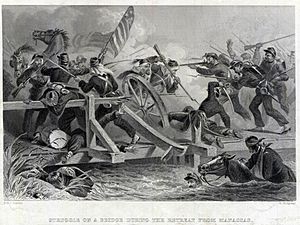

Struggle on a Manassas, Virginia bridge during the Union Army's retreat in 1861 depicted in an engraving by William Ridgway based on a drawing by F. O. C. Darley |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Irvin McDowell | Joseph E. Johnston P. G. T. Beauregard |

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Department of Northeastern Virginia:

|

Army of the Shenandoah | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Army of Northeastern Virginia:

Patterson's Command:

|

32,000–34,000 (c. 18,000 engaged) |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,708 481 killed 1,011 wounded 1,216 missing |

1,982 387 killed 1,582 wounded 13 missing |

||||||

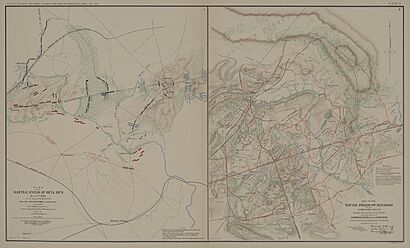

The First Battle of Bull Run, also known as the Battle of First Manassas by the Confederates, was the first big battle of the American Civil War. It happened on July 21, 1861, in Prince William County, Virginia. This area is just north of what is now the city of Manassas. It's also about 30 miles (48 km) west-southwest of Washington, D.C..

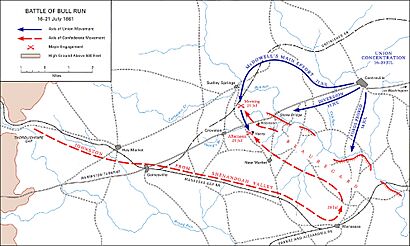

The Union Army was slow to get into position. This gave Confederate soldiers time to arrive by train. Both sides had about 18,000 soldiers. Many of these troops were not well-trained or well-led. The battle ended in a Confederate victory. After the battle, the Union forces had a very messy retreat.

Just a few months after the war began at Fort Sumter, people in the North wanted to march on Richmond, Virginia. Richmond was the Confederate capital. Many thought this would quickly end the war. Because of this public pressure, Brigadier General Irvin McDowell led his new Union Army. They marched across Bull Run to face the equally new Confederate Army. This army was led by Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard. His forces were camped near Manassas Junction.

McDowell had a plan for a surprise attack on the Confederate left side. But his plan was not carried out well. The Confederates had also planned to attack the Union's left. They found themselves at a disadvantage at first. However, Confederate reinforcements arrived. These troops were led by Brigadier General Joseph E. Johnston. They came from the Shenandoah Valley by railroad. The battle quickly changed. A group of Virginians, known as the Stonewall Brigade, stood firm. They were led by a lesser-known general, Thomas J. Jackson, from the Virginia Military Institute. This is how Jackson got his famous nickname, "Stonewall".

The Confederates then launched a strong counterattack. Union troops started to pull back under fire. Many panicked, and their retreat turned into a full-blown run. McDowell's soldiers ran without order toward Washington, D.C. Both armies were shocked by the fierce fighting and the many soldiers lost. They realized the war would be much longer and bloodier than anyone expected. The First Battle of Bull Run showed many problems common in the first year of the war. Units were sent into battle in small groups. Attacks were often head-on. Infantry failed to protect their cannons. Commanders had little information about the enemy. Neither side could use all their soldiers effectively. McDowell had 35,000 men but only used about 18,000. The Confederates had about 32,000 men but also only used 18,000.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The Start of the War

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina was the first Southern state to leave the United States. By February 1861, six more states followed. These states formed the Confederate States of America. On April 12, 1861, the war officially began. Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. This fort was held by the United States Army.

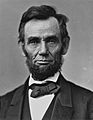

After Fort Sumter, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers. These soldiers would serve for 90 days. He later accepted more volunteers for three years. This made the U.S. Army much larger. Lincoln's actions caused four more Southern states, including Virginia, to join the Confederacy. On May 29, 1861, the Confederate capital moved from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond, Virginia.

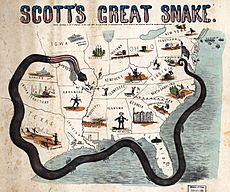

In Washington, D.C., many new volunteer regiments arrived to defend the capital. General Winfield Scott, the top U.S. general, suggested a plan. He wanted an army of 80,000 men to go down the Mississippi River and capture New Orleans. At the same time, the U.S. Navy would block Southern ports. Newspapers made fun of this plan, calling it the "Anaconda Plan". Instead, many people thought capturing Richmond, only 100 miles (160 km) south of Washington, would quickly end the war. By July 1861, thousands of Union volunteers were camped around Washington. General Scott was 75 and too old to lead the army in the field. So, the government looked for a new commander.

Choosing a Commander: Irvin McDowell

President Abraham Lincoln chose 42-year-old Major Irvin McDowell. McDowell had graduated from West Point. But he had little experience leading troops in battle. He had mostly worked in office jobs. Through political connections, McDowell was promoted to brigadier general. On May 27, he was given command of the Department of Northeastern Virginia. This included the troops around Washington, known as the Army of Northeastern Virginia.

McDowell quickly organized his army of 35,000 men into five divisions. People and politicians pressured him to start fighting. He had very little time to train his new soldiers. Units learned how to move together, but they didn't practice as larger groups. President Lincoln told him, "You are green, it is true, but they are green also; you are all green alike." Despite his doubts, McDowell began the campaign.

Secret Information

Before the battle, a U.S. Army captain named Thomas Jordan set up a spy network for the South in Washington, D.C.. He recruited Rose O'Neal Greenhow, a well-known socialite. She had many important contacts. Jordan gave her a secret code for messages. After he joined the Confederate Army, she took over his spy network. On July 9 and 16, Greenhow sent secret messages to Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard. These messages gave important details about Union troop movements. They even included Union General McDowell's battle plans.

McDowell's Plan and First Moves

On July 16, McDowell left Washington with the largest army ever seen in North America at that time. He had about 35,000 men. McDowell's plan was to move west in three groups. Two groups would make a fake attack on the Confederate line at Bull Run. The third group would go around the Confederates' right side to the south. This would cut off the railroad to Richmond and threaten the Confederate army from behind. He thought the Confederates would have to leave Manassas Junction and fall back. This would ease the pressure on Washington.

McDowell hoped his army would reach Centreville by July 17. But the soldiers were not used to long marches. They moved slowly, stopping often. Along the way, soldiers would leave their ranks to pick fruit or get water, even against orders.

The Confederate Army of the Potomac had about 22,000 men. They were led by Beauregard. They were camped near Manassas Junction. Beauregard set up defenses along the south bank of the Bull Run river. His left side protected a stone bridge. This was about 25 miles (40 km) from Washington. McDowell planned to attack this smaller enemy army. Meanwhile, Union Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson and his 18,000 men were supposed to keep Johnston's Confederate force busy in the Shenandoah Valley. This would stop Johnston from sending help to Beauregard.

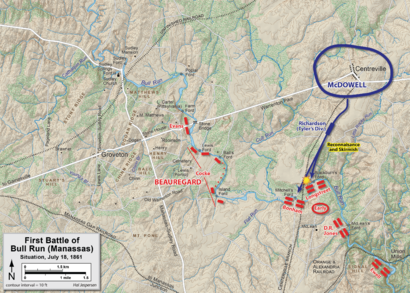

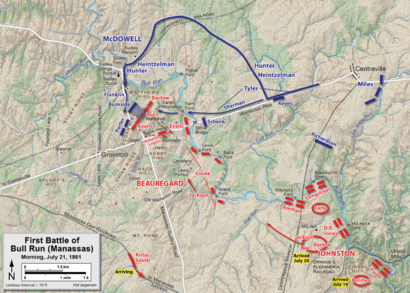

After two days of slow marching in the hot weather, the Union army rested in Centreville. McDowell sent about 5,000 troops to guard the army's rear. This reduced his main force to about 31,000. McDowell looked for a way to go around Beauregard's defenses along Bull Run. On July 18, he sent a division under Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler to attack the Confederate right side. Tyler got into a small fight at Blackburn's Ford but couldn't advance. Also on July 18, Johnston received a message. It suggested he help Beauregard if he could. Johnston marched out of Winchester around noon. His cavalry hid his movements from Patterson. Patterson was completely fooled. An hour after Johnston left, Patterson sent a telegram to Washington. He said he had successfully kept Johnston's force in Winchester.

McDowell felt he needed to act fast for his plan to work. He had heard rumors that Johnston had left the valley and was heading to Manassas Junction. If true, McDowell might soon face 34,000 Confederates instead of 22,000. Another concern was that the 90-day enlistments of many of his soldiers were about to end. "In a few days I will lose many thousands of the best of this force," he wrote to Washington. In fact, the next morning, two Union units whose enlistments expired that day refused to stay longer. They marched back to Washington, even as the battle sounds began.

Becoming more frustrated, McDowell decided to attack the Confederate left side instead. He planned for Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler's division to attack the Stone Bridge. This was on the Warrenton Turnpike. He would send the divisions of Brig. Gens. David Hunter and Samuel P. Heintzelman over Sudley Springs Ford. From there, these divisions could go around the Confederate line. They would march into the Confederate rear. A brigade led by Col. Israel B. Richardson would keep the enemy busy at Blackburn's Ford. This would stop them from interfering with the main attack. Patterson was supposed to keep Johnston busy in the Shenandoah Valley. This would prevent reinforcements from reaching the battle.

McDowell's plan sounded good on paper. But it had problems. It needed perfect timing for troop movements and attacks. His new army didn't have these skills. It also relied on Patterson's actions, which he had already failed to do. Finally, McDowell had waited too long. Johnston's troops, who had trained under Stonewall Jackson, were able to board trains. They rushed to Manassas Junction to help Beauregard's men.

Before the Battle

On July 19–20, many more Confederate soldiers arrived. Johnston came with almost all his army. Most of these new arrivals were placed near Blackburn's Ford. Beauregard's plan was to attack from there, heading north toward Centreville. Johnston, who was the higher-ranking officer, approved the plan. If both armies had attacked at the same time, they would have moved in opposite circles, each attacking the other's left side.

McDowell was getting confusing information from his spies. So, he called for the balloon Enterprise. Professor Thaddeus S. C. Lowe was showing it in Washington. McDowell wanted it to fly over the area and see what the Confederates were doing.

The Armies Involved

Union Forces

McDowell's Army of Northeastern Virginia had about 35,000 soldiers. They were organized into five infantry divisions. Each division had three to five brigades. Each brigade had three to five infantry regiments. An artillery battery (cannons) was usually with each brigade. Only about 18,000 Union troops actually fought in the battle.

Here are the main Union commanders:

- Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler led the 1st Division.

- Col. David Hunter led the 2nd Division.

- Col. Samuel P. Heintzelman led the 3rd Division.

- Brig. Gen. Theodore Runyon led the 4th Division, but his troops were not involved in the fighting.

- Col. Dixon S. Miles led the 5th Division.

Another Union force, led by Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson, had about 18,000 men. They were stationed near Harper's Ferry. Their job was to stop Confederate troops from the Shenandoah Valley.

Confederate Forces

The Army of the Potomac was led by Brig. Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard. It had about 22,000 soldiers. It was organized into seven infantry brigades. Each brigade had three to six infantry regiments. Cannon batteries were with different brigades. Beauregard's army also had 39 field cannons and a regiment of Virginia cavalry.

The Army of the Shenandoah was led by Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston. It had about 12,000 men. It had four brigades, each with three to five infantry regiments. Each brigade had one cannon battery. There were also 20 cannons and about 300 cavalrymen led by Col. J. E. B. Stuart.

Even though the two Confederate armies together had about 34,000 men, only about 18,000 actually fought at Bull Run.

Here are the main Confederate commanders:

- Brig. Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard commanded the Army of the Potomac.

- Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston commanded the Army of the Shenandoah.

- Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson led the 1st Brigade of the Army of the Shenandoah.

The Battle Begins

Morning Fighting

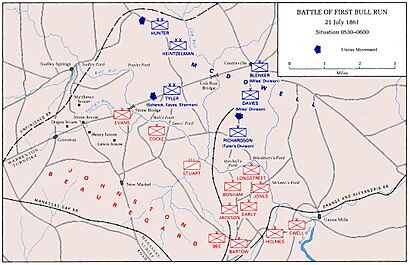

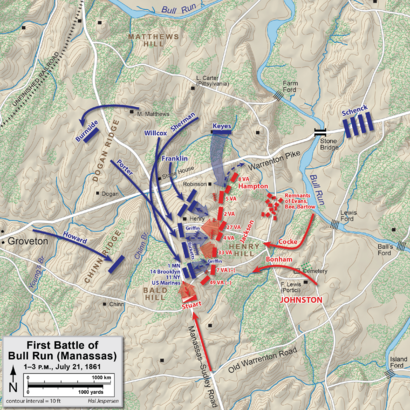

On the morning of July 21, McDowell sent Hunter's and Heintzelman's divisions (about 12,000 men) from Centreville. They started marching at 2:30 a.m. They went southwest on the Warrenton Turnpike, then turned northwest toward Sudley Springs. Their goal was to get around the Confederate left side. Tyler's division (about 8,000 men) marched straight toward the Stone Bridge.

The new Union units quickly had problems. Tyler's division blocked the main flanking column on the turnpike. The roads to Sudley Springs were bad, sometimes just cart paths. The later units didn't start crossing Bull Run until 9:30 a.m. Tyler's men reached the Stone Bridge around 6 a.m.

At 5:15 a.m., Richardson's brigade fired some cannon rounds across Mitchell's Ford. Some of these hit Beauregard's headquarters while he was eating breakfast. This told him that the Union had attacked first. Still, he ordered fake attacks toward the Union left at Centreville. But confused orders and bad communication stopped these attacks.

Only about 1,100 Confederate soldiers, led by Col. Nathan "Shanks" Evans, stood in the way of 20,000 Union soldiers. Evans had moved some of his men to stop Tyler at the bridge. But he started to think Tyler's attacks were just a trick. He learned about the main Union flanking movement through Sudley Springs from Captain Edward Porter Alexander. Alexander was Beauregard's signal officer. He was watching from 8 miles (13 km) away on Signal Hill. In the first use of wig-wag semaphore signaling in battle, Alexander sent the message: "Look out for your left, your position is turned." Evans quickly led 900 of his men from the Stone Bridge to Matthews Hill. This was a small rise northwest of his old spot.

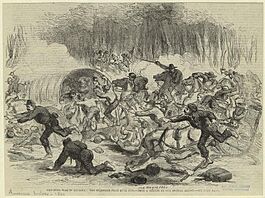

The Confederates tried to slow down the Union on Matthews Hill. Major Roberdeau Wheat's 1st Louisiana Special Battalion, "Wheat's Tigers", launched an attack. After Wheat's group was pushed back and Wheat was badly hurt, Evans got help. Two more brigades arrived, led by Brig. Gen. Barnard Bee and Col. Francis S. Bartow. This brought their force to 2,800 men. They successfully slowed down Hunter's lead brigade (Brig. Gen. Ambrose Burnside). This was happening as the Union tried to cross Bull Run and move across Young's Branch. One of Tyler's brigade commanders, Col. William Tecumseh Sherman, moved from the stone bridge around 10:00 a.m. He crossed at an unguarded spot and hit the right side of the Confederate defenders. This surprise attack, along with pressure from Burnside and Maj. George Sykes, broke the Confederate line. This happened shortly after 11:30 a.m. The Confederates retreated in a rush to Henry House Hill.

Noon Fighting: Henry House Hill

As they retreated from Matthews Hill, Evans's, Bee's, and Bartow's men got some cover. Capt. John D. Imboden and his four cannons held off the Union advance. This gave the Confederates time to regroup on Henry House Hill. Generals Johnston and Beauregard arrived there. Luckily for the Confederates, McDowell didn't immediately attack the hill. Instead, he chose to fire cannons at it.

Brig. Gen Thomas J. Jackson's Virginia Brigade arrived around noon to help the disorganized Confederates. Col. Wade Hampton and his Hampton's Legion, and Col. J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry also arrived with cannons. Hampton's Legion, about 600 men, helped Jackson set up a defense on Henry House Hill. They fired many shots at Sherman's advancing brigade. The 79th New York Union regiment was badly hit and started to break apart. Wade Hampton pointed to their colonel, James Cameron, and said, "Look at that brave officer trying to lead his men and they won't follow him." Soon after, Cameron, who was the brother of the U.S. Secretary of War, was killed.

Jackson placed his five regiments on the back slope of the hill. This protected them from direct fire. He also set up 13 cannons on the top of the hill. When the cannons fired, their kickback moved them down the slope, where they could be safely reloaded. Meanwhile, McDowell ordered his cannons to move closer to the hill for support. Their 11 cannons had a fierce fight against Jackson's 13 cannons from about 300 yards (274 m) away. Unlike many Civil War battles, the Confederate cannons had an advantage here. The Union cannons were now in range of the Confederate smoothbore cannons. The Union's rifled cannons were not good at such close range. Many of their shots went over their targets.

One person hurt by the cannon fire was Judith Carter Henry. She was an 85-year-old widow who was sick and couldn't leave her bedroom in the Henry House. When Union cannons started getting rifle fire, they thought it came from her house. They fired at the building. A shell crashed through her bedroom wall, badly injuring her. She died later that day.

As his men were pushed back, Bee called out to Jackson, "The Enemy are driving us." Jackson, a former U.S. Army officer and professor, is said to have replied, "Then, Sir, we will give them the bayonet." Bee then reportedly told his own troops to regroup by shouting, "There is Jackson standing like a stone wall. Let us determine to die here, and we will conquer. Rally behind the Virginians." This is often said to be how Jackson got his famous nickname, "Stonewall". Bee was shot soon after and died the next day. So, it's not fully clear what he said or meant.

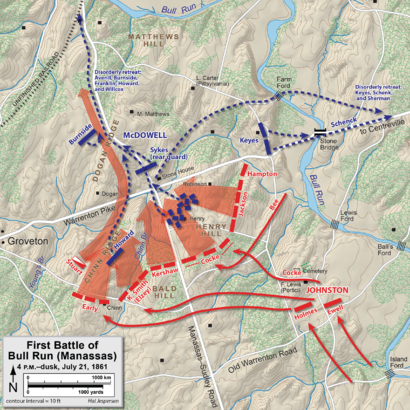

A Union artillery commander decided to move two of his cannons to the end of his line. He hoped to fire along the Confederate line. Around 3 p.m., these cannons were taken over by the 33rd Virginia regiment. These soldiers wore blue uniforms. This made the Union commander think they were his own troops. He ordered his men not to fire at them. Close-range shots from the 33rd Virginia followed. Then Stuart's cavalry attacked the side of the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment. This unit was supporting the cannons. Many Union gunners were killed, and the infantry scattered. Jackson used this success. He ordered two regiments to charge the Union cannons, and they were captured. As more Union infantry joined the fight, the Confederates were pushed back. But they regrouped, and the cannons changed hands several times.

The capture of the Union cannons changed the battle. McDowell had brought 15 regiments to the hill. This outnumbered the Confederates two to one. But no more than two Union regiments fought at the same time. Jackson kept pushing his attacks. He told soldiers, "Reserve your fire until they come within 50 yards! Then fire and give them the bayonet! And when you charge, yell like furies!" For the first time, Union troops heard the loud and scary "Rebel yell". Around 4 p.m., the last Union troops were pushed off Henry House Hill. This was by a charge of two regiments from Col. Philip St. George Cocke's brigade.

To the west, Chinn Ridge was held by Col. Oliver Otis Howard's brigade. But at 4 p.m., two Confederate brigades moved forward. These were Col. Jubal Early's, which had moved from the Confederate right, and Brig. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith's. Smith's brigade (led by Col. Arnold Elzey after Smith was wounded) had just arrived from the Shenandoah Valley. They crushed Howard's brigade. Beauregard ordered his whole line to advance. The Union troops began to panic and retreat. By 5 p.m., McDowell's army was falling apart everywhere. Thousands of soldiers, in groups or alone, left the battlefield and headed for Centreville. They were running away. McDowell rode around trying to rally his regiments, but most had had enough. He couldn't stop the mass exit. McDowell ordered a regular infantry battalion to act as a rear guard. This unit briefly held a crossroads, then retreated with the rest of the army. McDowell's force broke down and ran.

The Union Retreat

The retreat was somewhat orderly until the Bull Run crossings. But Union officers managed it poorly. A Union wagon was overturned by cannon fire on a bridge over Cub Run Creek. This caused panic among McDowell's troops. Soldiers ran wildly toward Centreville, throwing away their weapons and gear. McDowell ordered Col. Dixon S. Miles's division to guard the rear. But it was impossible to stop the army before Washington. In the chaos, hundreds of Union soldiers were captured. Wagons and cannons were left behind. This included a large 30-pounder Parrott rifle, which had started the battle with a bang.

Wealthy people from Washington, including politicians, had come to picnic and watch the battle. They expected an easy Union victory. When the Union army ran back in disorder, the roads to Washington were blocked. Panicked civilians tried to flee in their carriages. This messy retreat became known in the South as "The Great Skedaddle".

The Confederate army was also very disorganized after the battle. So, Beauregard and Johnston didn't fully push their advantage. This was despite Confederate President Jefferson Davis urging them to. Davis had arrived on the battlefield to see the Union soldiers retreating. Johnston tried to cut off the Union troops from his right side. He used the brigades of Brig. Gens. Milledge L. Bonham and James Longstreet. But this failed. The two commanders argued. When Bonham's men received some cannon fire from the Union rear guard, and found that Richardson's brigade blocked the road to Centreville, he called off the chase.

In Washington, President Lincoln and his cabinet waited for news of a Union victory. Instead, a telegram arrived saying, "General McDowell's army in full retreat through Centreville. The day is lost. Save Washington and the remnants of this army." The news was happier in the Confederate capital. From the battlefield, President Davis telegraphed Richmond, "We have won a glorious but dear-bought victory. Night closed on the enemy in full flight and closely pursued."

Aftermath of the Battle

What We Learned

The battle was a fight between large groups of new soldiers. They were led by officers who didn't have much experience. Neither army commander could use his forces well. Almost 60,000 men were at the battle, but only 36,000 actually fought. McDowell was active on the battlefield. But he spent most of his energy moving small groups of soldiers. He didn't control and coordinate his whole army.

Other things led to McDowell's defeat. Patterson failed to keep Johnston in the valley. McDowell delayed for two days at Centreville. He let Tyler's division lead the march on July 21. This slowed down the flanking divisions. There was also a 2.5-hour delay after the Union won on Matthews' Hill. This allowed the Confederates to bring in more soldiers and set up defenses on Henry Hill. On Henry Hill, Beauregard also only controlled small groups. He generally let the battle happen on its own. Johnston's choice to send his infantry to the battlefield by train was very important for the Confederate victory. Even though the trains were slow, most of his army arrived in time. After reaching Manassas Junction, Johnston gave command of the battlefield to Beauregard. But his sending of reinforcements was key. Jackson's and Bee's brigades did most of the fighting. Jackson's brigade fought almost alone for four hours and lost more than half its men.

Soldiers Lost

Bull Run was the biggest and bloodiest battle in U.S. history up to that point. The Union lost 460 killed, 1,124 wounded, and 1,312 missing or captured. The Confederates lost 387 killed, 1,582 wounded, and 13 missing. This was a high casualty rate for the soldiers who fought.

Among the Union dead was Col. James Cameron. He was the brother of President Lincoln's first Secretary of War. Among the Confederate casualties was Col. Francis S. Bartow. He was the first Confederate brigade commander killed in the Civil War. General Bee was badly wounded and died the next day.

Compared to later battles, the number of soldiers lost at First Bull Run wasn't extremely high. Both Union and Confederate forces lost a little over 1,700 soldiers each (killed, wounded, or missing). Two Confederate brigade commanders, Jackson and Edmund Kirby-Smith, were wounded. Jackson was shot in the hand but stayed on the battlefield. No Union officers above the regimental level were killed. Two division commanders and one brigade commander were wounded.

What Happened Next for the Union

People in the North were shocked by the defeat. They had expected an easy victory. Some Northerners had even gone to watch the battle and picnic. Both sides quickly realized the war would be longer and more brutal than they thought. On July 22, President Lincoln signed a bill. It allowed for 500,000 more men to join the army for up to three years.

The defeat at Bull Run, and another smaller defeat later, led to the creation of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. This group in Congress investigated how the Northern military was doing. They decided that Patterson's failure to stop Johnston was the main reason for the defeat. But Patterson's enlistment had ended, so he was no longer in the army. The public wanted someone to blame, and McDowell took most of it. On July 25, he was removed from army command. Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan replaced him. McDowell was also blamed for another defeat later, at the Second Battle of Bull Run.

What Happened Next for the Confederacy

The reaction in the Confederacy was quieter. There wasn't much public celebration. Southerners realized that even with their victory, future battles would mean more losses. After the excitement of victory faded, Jefferson Davis asked for 400,000 more volunteers.

Beauregard was seen as the Confederate hero. President Davis promoted him to full general that day. Stonewall Jackson, who was very important to the victory, didn't get special recognition right away. But he would later become famous for his 1862 Valley Campaign. Davis privately thanked Greenhow, the spy, for helping the Confederates win.

The battle also had long-term effects on how people thought. The clear victory made Confederate forces a bit too confident. It also made the Union more determined to organize their army better. Looking back, people on both sides agreed that the victory "proved the greatest misfortune that would have befallen the Confederacy."

Why the Name "Bull Run" or "Manassas"?

The name of the battle has been debated since 1861. The Union Army often named battles after important rivers or creeks nearby. The Confederates usually used the names of nearby towns or farms. The U.S. National Park Service uses the Confederate name for its park, Manassas National Battlefield Park. But the Union name (Bull Run) is also widely used.

Confusing Flags

During the battle, it was hard to tell the flags apart. The Confederacy's "Stars and Bars" looked a lot like the Union's "Stars and Stripes" when they were waving. This led to the Confederates creating a new flag, the Confederate Battle Flag. This flag later became a very popular symbol of the Confederacy and the South.

Key Takeaways

The First Battle of Bull Run showed that the war wouldn't be won in one big fight. Both sides started getting ready for a long and bloody conflict. The battle also showed how important it was to have well-trained and experienced officers and soldiers. One year later, many of the same soldiers, now experienced fighters, would return to the same battlefield for the Second Battle of Bull Run/Manassas.

Images for kids

-

Pres.

Abraham Lincoln,

USA -

Pres.

Jefferson Davis,

CSA -

Brig. Gen.

Irvin McDowell, (Commanding) -

Brig. Gen.

Daniel Tyler -

Brig. Gen.

David Hunter -

Brig. Gen.

Samuel P. Heintzelman -

Col.

Dixon S. Miles -

Maj. Gen.

Robert Patterson -

Brig. Gen.

P. G. T. Beauregard, Army of the Potomac -

Brig. Gen.

Joseph E. Johnston, Army of the Shenandoah

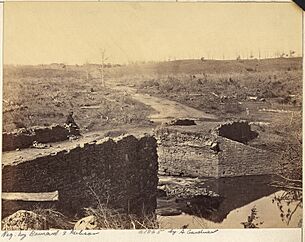

Visiting the Battlefield

Today, part of the battle site is the Manassas National Battlefield Park. It's a National Battlefield Park. Over 900,000 people visit it each year. The park is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The American Battlefield Trust and its partners have helped save over 385 acres (1.56 km²) of the Manassas battlefields since 2010.

See also

In Spanish: Primera batalla de Bull Run para niños

In Spanish: Primera batalla de Bull Run para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |