P. G. T. Beauregard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

P. G. T. Beauregard

|

|

|---|---|

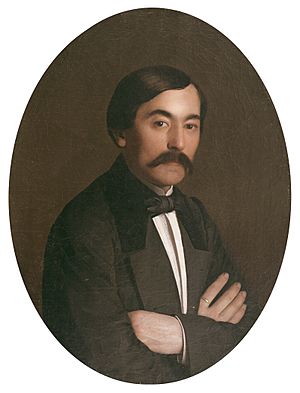

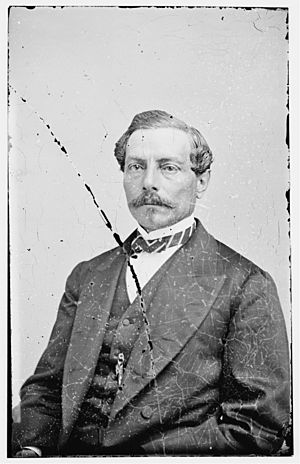

Portrait by Mathew Brady, c. 1860-1865

|

|

| Nickname(s) |

|

| Born | May 28, 1818 St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | February 20, 1893 (aged 74) New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Buried |

Tomb of the Army of Tennessee, Metairie Cemetery, New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S.

|

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank |

|

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Children | Henry Beauregard

Laure Beauregard René Beauregard |

| Signature | |

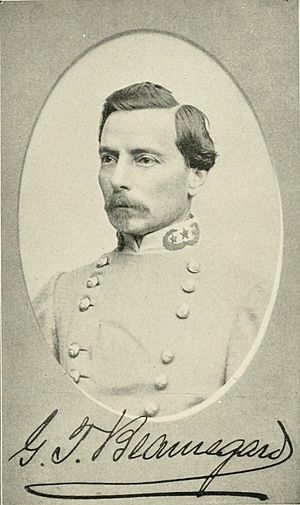

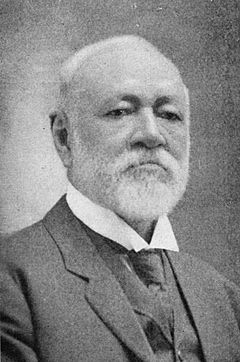

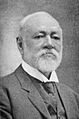

Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard (born May 28, 1818 – died February 20, 1893) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War. He was from a Louisiana Creole family. He is famous for starting the Civil War by leading the attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. People today often call him P. G. T. Beauregard. But he usually signed his letters as G. T. Beauregard.

Beauregard studied military and civil engineering at West Point. He was a skilled engineer officer in the Mexican–American War. After a short time as superintendent of West Point in 1861, he left the United States Army. This happened when Louisiana left the Union. He then became the first brigadier general in the Confederate States Army. He commanded the defenses of Charleston, South Carolina, at the start of the Civil War. Three months later, he won the First Battle of Bull Run near Manassas, Virginia.

Beauregard led important armies in the Western part of the war. This included battles like Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee and the Siege of Corinth in Mississippi in 1862. He later returned to Charleston and defended it in 1863 from Union attacks. He is best known for defending Petersburg, Virginia, in June 1864. This delayed the fall of the Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia, until April 1865.

His ideas for Confederate strategy were sometimes ignored. This was because he often disagreed with President Jefferson Davis and other generals. In April 1865, Beauregard and General Joseph E. Johnston convinced Davis that the war had to end. Johnston surrendered most of the remaining Confederate armies, including Beauregard's men, to Major General William Tecumseh Sherman.

After the war, Beauregard went back to Louisiana. He supported civil rights for black people, including their right to vote. He also worked as a railroad executive and became rich as a promoter of the Louisiana Lottery.

Contents

Growing Up and School

Beauregard was born on a sugar-cane farm called "Contreras". This farm was in St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, about 20 miles (32 km) from New Orleans. His family was Louisiana Creole. His mother, Hélène Judith de Reggio, had French and Italian ancestors. His father, Jacques Toutant-Beauregard, had French and Welsh ancestors. Pierre was the third of seven children. Like many Louisiana Creoles, his family spoke French and were Roman Catholic.

As a child, Beauregard played with enslaved boys his age. He grew up in a large, fancy one-story house. He loved to hunt and ride horses in the woods around his family's farm. He also paddled his boat in the local waterways. Beauregard went to private schools in New Orleans. Then, at age 12, he went to a "French school" in New York City. During his four years there, he learned to speak English. French had been his only language before this.

He then attended the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. One of his teachers was Robert Anderson. Anderson later became the commander of Fort Sumter and surrendered to Beauregard at the start of the Civil War. When Beauregard joined West Point, he dropped the hyphen from his last name. He used "Toutant" as a middle name to fit in with his classmates. From then on, he rarely used his first name, preferring "G. T. Beauregard." He graduated second in his class in 1838. He was very good at artillery and military engineering. His Army friends gave him many nicknames. These included "Little Creole," "Bory," "Little Frenchman," "Felix," and "Little Napoleon."

Early Military Career

During the Mexican–American War, Beauregard worked as an engineer. He served under General Winfield Scott. He was made a temporary captain for his actions at Contreras and Churubusco. He became a temporary major at Chapultepec, where he was wounded. He was praised for convincing General Scott to change the plan for attacking Chapultepec. He was one of the first officers to enter Mexico City. Beauregard felt he deserved more recognition than other engineers, like Captain Robert E. Lee.

After the war, Beauregard returned in 1848. For the next 12 years, he worked on defenses along the Mississippi River and lakes in Louisiana. He also repaired old forts and built new ones in Florida and Alabama. He improved the defenses of Forts St. Philip and Jackson near New Orleans. He also helped improve shipping channels at the mouth of the Mississippi. He even invented a device to help ships cross sandbars.

Beauregard became unhappy as a peacetime officer. He briefly entered politics in 1858. He ran for mayor of New Orleans but lost. In 1861, he became superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy. But when Louisiana left the Union, the government quickly removed him. He left his post after only five days.

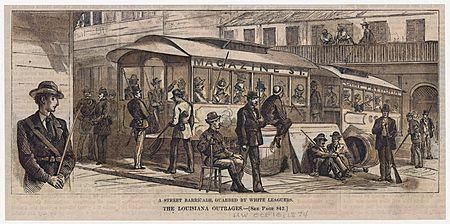

American Civil War

Charleston: The War Begins

Beauregard traveled from New York to New Orleans. He immediately gave military advice to Louisiana leaders. He hoped to lead Louisiana's state army. But he was disappointed when Braxton Bragg was chosen instead. Beauregard then joined a group of French Creole aristocrats as a private. He also talked with President Davis to get a high position in the new Confederate Army.

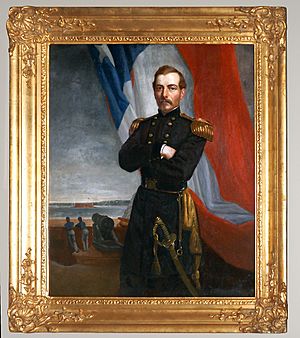

Davis chose Beauregard to command Charleston's defenses. Beauregard was seen as a good military engineer and a strong Southern leader. He became the first Confederate general officer on March 1, 1861. Later, on July 21, he was promoted to full general. He was one of only seven men to reach this rank.

Beauregard arrived in Charleston on March 3, 1861. He checked the harbor defenses, which were messy. Major Robert Anderson, his former teacher, commanded Fort Sumter. Anderson believed Beauregard would act with "skill and sound judgment." Beauregard sent gifts to Anderson, but they were returned.

By early April, tensions were high. Beauregard demanded that Fort Sumter surrender. On April 12, 1861, negotiations failed. Beauregard ordered the first shots of the Civil War to be fired. The attack on Fort Sumter lasted 34 hours. Anderson surrendered the fort on April 14. Beauregard was praised as "The Hero of Fort Sumter."

First Bull Run: A Big Victory

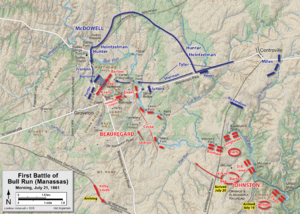

Beauregard was called to Richmond, Virginia, the new Confederate capital. He was given a hero's welcome. He took command of the "Alexandria Line" defenses. This was to stop a Union attack led by Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell. Beauregard planned to combine his forces with General Joseph E. Johnston's army. He wanted to defend his position and attack Washington.

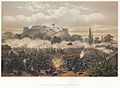

The First Battle of Bull Run (also called First Manassas) began on July 21, 1861. Both armies planned surprise attacks. McDowell attacked first, threatening Beauregard's left side. Beauregard wanted to attack on his right. But Johnston told him to go to the threatened area at Henry House Hill. Beauregard rallied his troops, riding among them and giving speeches. The Confederate line held strong.

As Johnston's last troops arrived, the Confederates counterattacked. The Union Army was defeated and fled back to Washington. Beauregard received much praise for this victory. On July 23, Johnston suggested Beauregard be promoted to full general. Davis agreed, making Beauregard a full general on July 21, the day of his victory.

After Bull Run, Beauregard wanted a new battle flag. The original Confederate flag looked too much like the U.S. flag. He worked with Johnston to create the Confederate Battle Flag. Women helped make the first flags from their dresses. This flag became a very popular symbol of the Confederacy.

During the winter, Beauregard had disagreements with Confederate leaders. He wanted to invade Maryland, but his plan was rejected. He also complained about supplies for his army. He angered President Davis by publishing a report about Bull Run. The report suggested Davis's actions stopped a full Confederate victory.

Shiloh and Corinth: Challenges in the West

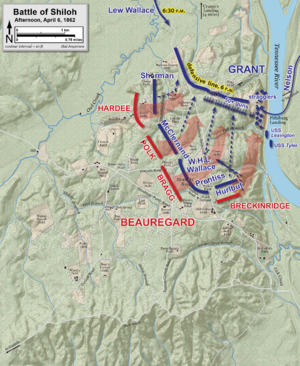

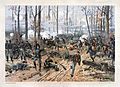

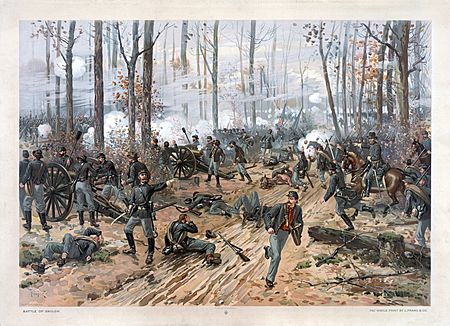

Because of his disagreements in Virginia, Beauregard was sent to Tennessee. He became second-in-command to General Albert Sidney Johnston on March 14, 1862. They planned to stop Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant from joining another Union army. The march was slow due to bad weather. Beauregard thought their surprise was lost and wanted to cancel the attack. But Johnston decided to continue.

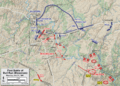

The Battle of Shiloh began on April 6, 1862. The Confederates launched a surprise attack on Grant's army. Beauregard's plan for the attack caused confusion among units. In the afternoon, Johnston was badly wounded and died. Beauregard took command of the army. As night fell, he stopped the attack. He believed his men could finish off Grant in the morning.

Beauregard's decision to stop the attack was very controversial. Many wondered what would have happened if they had continued fighting. Unknown to Beauregard, another Union army arrived that afternoon. On April 7, Grant and the new army launched a huge counterattack. The Confederates were overwhelmed and retreated to Corinth.

Grant was blamed for the surprise attack. His superior, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, took command. Halleck slowly approached Beauregard's defenses at Corinth. This became known as the Siege of Corinth. Beauregard tricked Halleck into thinking he was about to attack. He ran empty trains back and forth to make noise. Beauregard then withdrew from Corinth on May 29 to Tupelo, Mississippi. He left because of the large Union force and bad water supplies. Many Confederate soldiers died from disease in Corinth. When Beauregard took medical leave without permission, President Davis removed him from command. Gen. Braxton Bragg replaced him.

Defending Charleston Again

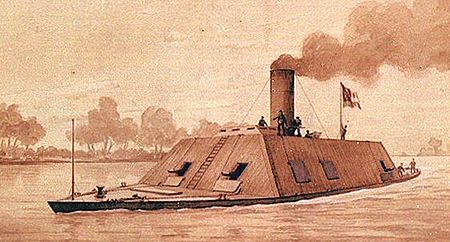

Beauregard was ordered to Charleston. He took command of coastal defenses in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. He was unhappy, wanting to lead a larger army. However, he successfully defended Charleston from Union attacks in 1863. On April 7, 1863, Union ironclad ships attacked Fort Sumter. Beauregard's forces used accurate artillery fire to push them back.

From July to September 1863, Union land forces attacked Fort Wagner and other forts. Union ships also tried to destroy Fort Sumter. These attacks failed to capture Charleston.

During this time, Beauregard developed new naval defense ideas. He experimented with early submarines and naval mines (called "torpedoes"). He also worked on a small vessel called a torpedo-ram. This boat had a torpedo on a pole to surprise enemy ships underwater. He also suggested peace talks between Union and Confederate governors. The Davis administration rejected this idea.

Beauregard also proposed a grand strategy. He wanted to send more troops to the Western armies. This would defeat the Federal army in Tennessee. It would also force Grant to leave Vicksburg. Then, the Confederate army could move into Ohio. He hoped this would make Western states join the Confederacy. He also wanted to use British-built torpedo-rams to retake New Orleans. There is no record that his plan was officially presented.

While visiting his forces in Florida, Beauregard learned his wife had died on March 2, 1864. She had been ill for two years in Union-occupied New Orleans. A local newspaper suggested her condition worsened due to her husband's actions. This made many people attend her funeral. Beauregard wished he could rescue "her hallowed grave" with an army.

Defending Richmond and Petersburg

In April 1864, Beauregard felt there was little chance for glory in Charleston. He asked for a break due to fatigue. Instead, he was ordered to Virginia. His new job was to defend Virginia south of the James River. He renamed his command the Department of North Carolina and Southern Virginia. The Confederates were preparing for Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's spring attack. They worried about attacks south of Richmond that could cut off supply lines.

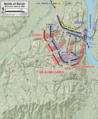

As Grant moved south, Union Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler launched a surprise attack. This was the Bermuda Hundred Campaign. Beauregard successfully argued against sending his small force north to help Lee. His quick actions, combined with Butler's mistakes, trapped the Union army. This removed their threat to Petersburg and Lee's supply line. Beauregard did send one division to Lee for the Battle of Cold Harbor. Lee wanted more troops and offered Beauregard command of his army's right side. Beauregard replied that he would do anything for success but needed orders to leave his department.

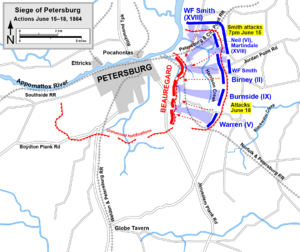

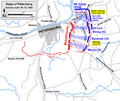

After Cold Harbor, Lee and his generals did not know Grant's next move. But Beauregard correctly predicted it. Grant crossed the James River to capture Petersburg. Petersburg was lightly defended but had key rail lines for Richmond and Lee. Beauregard pleaded for reinforcements but could not convince others of the danger. On June 15, his small force of 5,400 men defended against 16,000 Union soldiers. This was the Second Battle of Petersburg. He took a risk by moving his Bermuda Hundred defenses to Petersburg. He correctly guessed that Butler would not attack the empty defenses. His gamble worked. He held Petersburg long enough for Lee's army to arrive. This was one of his best performances in the war.

Beauregard continued to command Petersburg's defenses during the early siege. But after losing the Weldon Railroad, he was criticized. He also became unhappy with how he was commanded under Lee. He wanted an independent command. However, Lee chose Jubal Early to lead an expedition north. Davis chose John Bell Hood to replace Joseph E. Johnston in the Atlanta campaign.

Final Days in the West

After Atlanta fell in September 1864, President Davis thought about replacing John Bell Hood. He asked Robert E. Lee if Beauregard was interested. Beauregard was interested, but Davis kept Hood. Davis met Beauregard on October 2 and offered him command of the new Department of the West. This department covered five Southern states. Hood's and Richard Taylor's armies were under his command. However, it was mostly a job for logistics and advice. He only had real control if he joined the armies in person during an emergency. Still, he accepted the job.

Hood's main operation that fall was the Franklin-Nashville Campaign into Tennessee. Beauregard stayed in touch with Hood. They became friends, and Beauregard later helped publish Hood's memoirs.

While Hood was in Tennessee, Union Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman began his March to the Sea. This march went from Atlanta to Savannah. Beauregard could not stop Sherman's advance. He had too few local forces. He also did not want to remove defenses from other areas. Sherman also did a good job of hiding his true targets. Savannah fell on December 21. Sherman's army then marched north into South Carolina in January. Beauregard also learned that Hood's army was badly defeated at the Battle of Nashville. There were few men left to stop Sherman.

Beauregard tried to gather his small forces before Sherman reached Columbia, South Carolina. His urgent messages to Richmond were not believed. Davis and Robert E. Lee did not think Sherman could advance so quickly without supplies. Lee also worried about Beauregard's "feeble health." Lee suggested that Joseph E. Johnston replace Beauregard. The change happened on February 22. Beauregard was disappointed but worked with Johnston. For the rest of the war, Beauregard was Johnston's subordinate.

Johnston and Beauregard met with President Davis on April 13. Their assessment helped convince Davis that Johnston should meet Sherman to surrender his army. They surrendered to Sherman near Durham, North Carolina, on April 26, 1865. Beauregard then traveled to New Orleans. In August, his house was surrounded by troops looking for a Confederate fugitive. Beauregard and his family were held overnight. He complained to General Philip Sheridan, who was annoyed by the treatment of his former enemy.

Life After the War

Later Years and New Careers

After the war, Beauregard was hesitant to swear loyalty to the U.S. government. But Lee and Johnston advised him to do so. He took the oath in New Orleans on September 16, 1865. He received a pardon from President Andrew Johnson in 1868. His right to run for public office was restored in 1876 by President Grant.

Beauregard was offered a position in the Brazilian Army in 1865 but declined. He said he preferred to live in the U.S., even if poor. He also turned down offers to command armies in Romania and Egypt.

Beauregard worked to end harsh penalties on Louisiana during Reconstruction. He was angry about high property taxes. This made him consider leaving the U.S. until 1875. He was active in the Reform Party. This group of New Orleans businessmen supported black civil rights and voting. They tried to unite black and white Louisianians to remove the Radical Republicans from power.

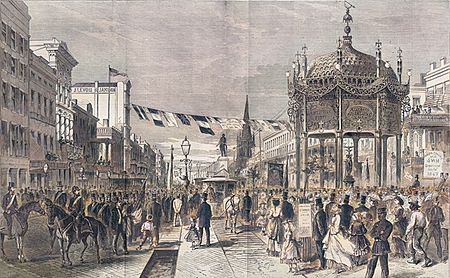

Beauregard's first job after the war was in October 1865. He became chief engineer and general superintendent of the New Orleans, Jackson and Great Northern Railroad. In 1866, he became president until 1870. He also served as president of the New Orleans and Carrollton Street Railway (1866–1876). Here, he invented a system of cable-powered street railway cars. He made the company successful but was fired by stockholders.

In 1869, he showed off his cable car invention and received a patent for it.

After losing his railway jobs, Beauregard worked for various companies. His personal wealth came from being a supervisor for the Louisiana State Lottery Company in 1877. He and former general Jubal Early oversaw lottery drawings. They made many public appearances, which gave the lottery some respect. They worked there for 15 years. But people became against government-sponsored gambling, and the lottery was closed.

Beauregard wrote military books, including Principles and Maxims of the Art of War (1863). He also co-authored a book about his military operations. He wrote an article about the Battle of Bull Run for a magazine. During these years, Beauregard and Davis often blamed each other for the Confederate defeat.

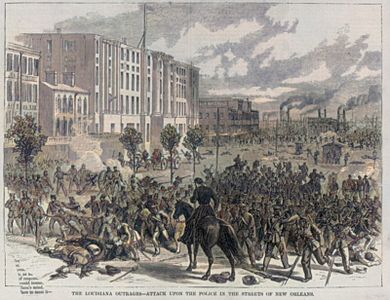

Beauregard served as adjutant general for the Louisiana state militia from 1879–88. In 1887, the militia was called to protect strikebreakers and stop sugar worker strikes. This led to violence, including the Thibodaux Massacre.

In 1888, he was elected as commissioner of public works in New Orleans. When John Bell Hood and his wife died in 1879, leaving ten orphans, Beauregard helped publish Hood's memoirs. All money from the book went to the children. He was asked to lead the ceremony for Robert E. Lee's statue in Richmond. But when Jefferson Davis died in 1889, Beauregard refused to lead the funeral. He said, "We have always been enemies. I cannot pretend I am sorry he is gone."

Beauregard died in his sleep in New Orleans. He was buried in the vault of the Army of Tennessee in Metairie Cemetery.

Personal Life

In 1841, Beauregard married Marie Antoinette Laure Villeré (1823-1850). She was the daughter of a Louisiana sugar planter. They had three children: Rene (1843-1910), Henri (1845-1915), and Laure (1850-1884). Marie died while giving birth to Laure. In 1860, Beauregard married Caroline Deslonde (1831-1864). She died in New Orleans after a long illness.

Supporting Civil Rights

His Creole Background and How Others Saw Him

In his younger years, Beauregard lived and served mostly with Anglo-Americans in the U.S. Army. This was unusual for Louisiana Creoles. During the Civil War, he fought almost only with Anglo-American Confederates. Many of his peers were against Catholics and foreigners. They often ignored his ideas during the war. For example, they didn't listen to his advice about defending New Orleans. Because he was a Creole Frenchman and seemed different, many rumors spread about him in the Confederacy.

One rumor after the Battle of Shiloh said he was crying in a tent. Another rumor from the Confederate media said he was insane.

People who were not Creole often thought he was immoral. This was partly because ladies liked him and sent him many gifts. During the war, he had a black man named Frederick Maginnis as a close friend. Beauregard talked freely with him about his war plans. He also had a young Spanish man who was his barber and valet. Beauregard always tried to act more "American" to fit in. For example, he refused to use his first name, 'Pierre'. He always signed his name 'G.T. Beauregard' so he wouldn't seem foreign.

When the Civil War ended, Beauregard returned to Louisiana. It had been under Union control and had adopted many Anglo-American racial policies.

Changing Political Views After the War

Reconstruction was a time of great change and tension. Racial tension and political disagreements grew. Two main parties, Republican and Democrat, now held power. Also, all men, not just the wealthy, could now vote.

In Louisiana, before the war, only the rich planters could vote. Now, all men could vote. Republicans mostly supported Northern interests like industry. Democrats mostly supported Southern interests like rebuilding farms. In the South, poor white people often voted Democrat. Newly freed black people often voted Republican. Voting and racial tensions led to protests, fights, and riots. New Orleans was divided.

Beauregard was insulted and even ridiculed in New Orleans. He feared being arrested or exiled for joining the Confederacy. Federal troops once surrounded his home looking for Confederate fugitives. They held Beauregard and his family in a cotton press overnight while searching his house.

In 1865, Beauregard was in a very difficult place. As Reconstruction began, Southern Democrats blamed newly freed black people for the poverty and destruction after the war. Beauregard wrote a letter echoing these ideas. He said freed black people were inferior and lazy. At this time, he was a Democrat.

Beauregard's Views During Reconstruction

In the years after Reconstruction began, Beauregard's opinions changed. Unlike other former Confederates, his financial situation improved. His home state of Louisiana seemed to be recovering. Beauregard became a strong voice in Louisiana during Reconstruction. He wrote many letters, gave interviews, and made speeches about various issues.

In March 1867, Radical Republicans gave black people the right to vote. Many Southerners were angry. But Beauregard wrote a widely published letter advising Southerners to accept this. He said they could either submit or resist, and resistance was pointless.

Beauregard wanted to end the fighting between Democrats and Republicans. He believed that cooperation between races through voting could create a better future for the South. He argued that freed black people were from the South. He said they only needed education and property to take part in Southern politics.

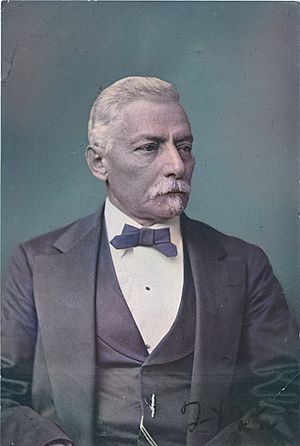

In 1868, Beauregard met with Robert E. Lee and other famous Confederates. They also met with William Rosecrans, a former Union general. The goal was to show that Southerners could treat freed black people fairly. They signed a document stating the South accepted the war's results and emancipation. They said they felt kindly towards freed black people, even if they opposed their political power.

Rosecrans later said that Lee's efforts were weak but sincere. When asked about Beauregard, Rosecrans said, "By the side of Lee, certainly. Take him alone, however, and he strikes you as quick, ready and incisive—well, a man of the world, a good business character, a smart active Frenchman. But with Lee he dwindles." When asked if Southern generals would let freed black people vote, Rosecrans replied, "Lee will not, probably, but Beauregard will. He is in favor of it."

Beauregard greatly admired Abraham Lincoln. In 1889, he was invited to ceremonies honoring Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois. Beauregard wanted to go but could not. He sent a message saying he would be there in spirit to pay his respects.

Political Activism for Unity

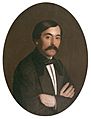

| Dernier Tribut (English: Last Tribute) by Victor E. Rillieux (1893)

French: Oh! chez lui l'on peut dire avec toute franchise, English: Oh! Of him we can say with all frankness, |

Beauregard continued to vote Republican. But Radical Republicans kept high taxes on the South. He looked for ways to improve his state's economy. In a public letter, he supported Horace Greeley, the 1872 Liberal Republican candidate. He called for peace, reconciliation, and unity. He wanted to remove corruption and high spending from the government.

In 1872, Beauregard became active in politics again. He helped form the Reform Party of Louisiana. This Southern party was made of Louisiana businessmen. They wanted an efficient state government. They also recognized black civil and political rights. The Reform Party demanded that the South accept black political power. They tried to replace the Democratic party. They also wanted to end Radical Republican taxes.

In 1873, the Reform Party created a plan for cooperation between races. This plan led to the Louisiana Unification Movement. Newspapers received many letters and interviews supporting the movement. Most were from New Orleans businessmen. They said they would work with black people and accept their political equality. In return, they wanted help to lower taxes and end racial tension. The Unification movement's slogan was "Equal Rights! One Flag! One Country! One People!"

The Louisiana Unification Movement

Beauregard spoke with Lieutenant Governor Caesar Antoine, a Creole Republican. He invited fifty leading white and fifty black New Orleans families to a meeting on June 16, 1873. The white sponsors were business, legal, and journalism leaders. Presidents of almost every city corporation and bank attended. The black sponsors were wealthy, educated Creoles of color. They had been free before the war. Beauregard led the committee that wrote the resolutions.

The meeting produced a report. It called for full political equality for black people. It also suggested an equal division of state offices between races. It had a plan for black people to become landowners. The report spoke against discrimination based on color in hiring or selecting company directors. It also called for ending segregation in public transport, public places, and schools. Beauregard argued that black people "already had equality and the whites had to accept that hard fact."

His Civil Rights Legacy

Beauregard lived a life of contrasts. Unlike many former Confederates, he did not dwell on the past. He looked to the future of Louisiana, its industry, and a better tomorrow.

Many admired Beauregard for his work after the war. In 1889, he attended a meeting in Waukesha, Wisconsin. A reporter called him "Sir Galahad of Southern Chivalry." A Northerner welcomed Beauregard. He said that 25 years ago, the North "did not feel very kindly toward him." But now, they admired him. Beauregard replied, "As to my past life, I have always endeavored to do my duty under all circumstances." He received loud applause.

After Beauregard died in 1893, Victor E. Rillieux wrote a poem. Rillieux was a Creole of color and a poet. He wrote poems for civil rights activists like Ida B. Wells. His poem, "Dernier Tribut" (meaning "Last Tribute"), honored Beauregard.

Legacy

Beauregard's home at 1113 Chartres Street in New Orleans is now a museum. It is called the Beauregard-Keyes House.

Beauregard Parish in western Louisiana is named after him. So is Camp Beauregard, a former U.S. Army base near Pineville. The town of Beauregard, Alabama, and Beauregard, Mississippi, are also named for him. Four camps of the Sons of Confederate Veterans are named after Beauregard.

An equestrian monument of him by Alexander Doyle was in New Orleans. The monument was removed on May 17, 2017.

Beauregard was played by Donald Sutherland in the 1999 TV movie The Hunley.

Beauregard Hall is an instructional building at Nicholls State University.

Dates of Rank

| Insignia | Rank | Date | Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| No insignia | Cadet, USMA | July 1, 1834 | Regular Army |

| Second Lieutenant | July 1, 1838 | Regular Army | |

| First Lieutenant | June 16, 1839 | Regular Army | |

| Captain | August 20, 1847 (temporary) March 3, 1853 (permanent) |

Regular Army | |

| Major | September 13, 1847 (temporary) | Regular Army | |

| Brigadier General | March 1, 1861 | Provisional Army of the Confederate States | |

| General | July 21, 1861 | Confederate States Army |

Images for kids

In Spanish: P. G. T. Beauregard para niños

In Spanish: P. G. T. Beauregard para niños