Battle of Liberty Place facts for kids

The Battle of Liberty Place, also known as the Battle of Canal Street, was a big fight that happened in New Orleans, Louisiana, on September 14, 1874. It was an attempt by a group called the White League to take over the state government. At this time, the United States was going through a period called Reconstruction Era, after the Civil War. The White League was a powerful group made up mostly of former Confederate soldiers. They used violence to try and scare people and get their way.

About 5,000 members of the White League fought against the smaller group of 3,500 police officers and state militia members. The White League managed to take control of the statehouse, the armory (where weapons are kept), and the downtown area for three days. They left only when the United States Army arrived to help restore the elected government. No one from the White League was charged for their actions. This battle was the last major violent event connected to a very close and argued election for governor in Louisiana in 1872. In that election, both the Democrat John McEnery and the Republican William Pitt Kellogg said they had won.

Quick facts for kids Battle of Liberty Place |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Reconstruction Era | |||||||

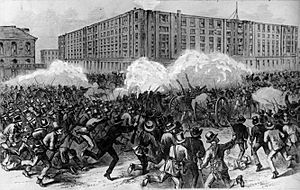

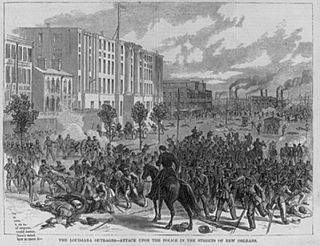

The "Louisiana Outrages", as illustrated in Harper's Weekly, 1874 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| White League |

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Frederick Nash Ogden | James Longstreet (WIA) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,000 | 3,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 21+ killed 19 wounded |

11 killed 60 wounded |

||||||

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

Political Tensions in Louisiana

The "Battle of Liberty Place" was the name given to this event by its supporters. They were Democrats who wanted to remove the Republican government that was in charge during Reconstruction. This government had brought more fairness and chances for African Americans. However, some white people, who believed white people were superior, saw this as unfair control.

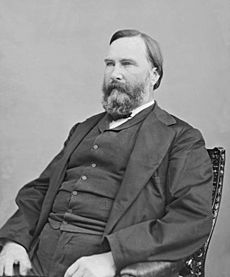

In the 1872 election for governor, Democrat John McEnery was supported by a mix of Democrats and some Republicans. The other Republican candidate, William Pitt Kellogg, was supported by President Ulysses S. Grant.

Disputed Election of 1872

The governor at the time, Henry C. Warmoth, was a Republican. He had a board that managed elections, and this board said McEnery won. But another board said Kellogg won. Kellogg claimed there was cheating and violence during the election. This violence was used to stop Black citizens from voting.

Governor Warmoth was later removed from office because of the election issues. Lieutenant Governor P. B. S. Pinchback then became governor for a short time. Both McEnery and Kellogg held their own inauguration parties. The United States government eventually said Kellogg was the official governor.

Earlier Violence: Colfax Massacre

Before the Battle of Liberty Place, there was another violent event in April 1873. This was called the Colfax massacre. It happened in Grant Parish. A white group attacked freed slaves who were protecting Republican officials. This event also showed the strong tensions between white and Black people. In Colfax, three white people and about 150 Black people were killed. Many of the Black people were killed after they had already been captured.

In 1874, McEnery and his supporters formed their own unofficial government in New Orleans. The White League, with 5,000 members, came into the city to help McEnery take power. They fought against 3,500 police and state militia members. The White League won this fight, causing about 100 injuries. They took over the state house and armory for three days. They also forced Governor Kellogg out.

When former Confederate general James Longstreet tried to stop the fighting, he was pulled from his horse and captured by the White League. Governor Kellogg quickly asked for help from the federal government. Within three days, President Ulysses S. Grant sent federal troops. The White League left New Orleans before the troops arrived, and no one was punished for their actions.

The Battle Begins

Gathering on Canal Street

People gathered on Canal Street on Monday morning to protest. They were upset because private citizens' weapons had been taken away. A group of leaders went to meet the governor, but he refused to see them. The governor believed the crowd was armed and dangerous. The leaders said the crowd was not armed, but the governor said armed groups were gathering nearby.

Around 4:00 in the afternoon, D. B. Penn, who claimed to be the lieutenant governor, called for the state militia to gather. He wanted them to "drive the people in power out." Frederick Nash Ogden was made the temporary general of this "Louisiana State Militia," which was really the White League. A message was sent to Black citizens, promising their rights and property would be safe.

Clash on Canal Street

By 3 PM, armed men were positioned on streets south of Canal Street. At 4 PM, a group of police with cavalry and cannons, led by Longstreet, arrived at Canal Street. They told the armed citizens to leave. But fighting started, and the police broke apart. The White League captured one of their cannons.

The White League then took over City Hall and the fire alarm system. They built blockades using streetcars along Poydras Street. A small group of federal troops protected the Custom House but did not join the fight at first. The White League controlled the part of the city above the canal. They gathered around Jackson Square and the St. Louis Hotel.

Casualties

Several police officers were killed in the battle. Some of the White League members were also killed, including E. A. Toledano and Frederick Moreman. Many more people were injured. Algernon Sidney Badger, the head of the New Orleans Metropolitan Police, was badly hurt. His leg was crushed when his horse was killed, and he had to have his leg removed.

After the Battle: The Siege

Governor Kellogg, Longstreet, and others found safety in the Custom House on September 14 and 15. By September 17, federal troops began to arrive. The situation changed, and the federal general, William H. Emory, met with the White League leaders. He promised they would not be arrested if they gave back control of the state government. They also had to return the weapons they took from the state arsenal.

The White League leaders agreed. They said no force was needed to make them surrender. However, they also said they no longer saw Louisiana as a state, but as a "province" without a true democratic government. Later that day, a rumor spread that a large group of Black citizens planned to take over a train station. But this disturbance was quickly stopped. More federal troops and naval ships were sent to New Orleans. By September 21, the surrender was complete. The temporary police force in the city was replaced by the regular forces.

What Happened Next

Continued Political Struggle

President Grant ordered General Philippe Régis de Trobriand and his soldiers to stay in New Orleans. Their job was to protect the state government from more violence. On January 4, 1875, Governor Kellogg asked for their help. He wanted to remove some men from the legislature who had not been officially approved. General Trobriand entered the state house with his soldiers. He escorted the eight men out after they had given speeches protesting.

The Democrats never returned to that legislature. They set up their own separate legislature in another building. They supported their candidate, Francis T. Nicholls, as governor for the next two years. During this time, the Republican governor, Stephen B. Packard, and his lawmakers only controlled a small part of New Orleans. White Democrats outside the city supported Nicholls. General Trobriand and his soldiers stayed in the city until January 1877. This was when federal troops were removed from the South as part of the Compromise of 1877.

The Monument

In 1891, the city of New Orleans built the Battle of Liberty Place Monument. It was made to remember and praise the White League's actions. At that time, the Democratic Party was in strong control of the city and state. They were also taking away voting rights from most Black citizens. The white marble monument was placed in a very noticeable spot on Canal Street.

In 1932, the city added words to the monument that showed a view of white people being superior. In 1974, after the Civil Rights Movement, people started to think differently about race. The city then added another marker near the monument. This marker explained that the original words did not show what people believed anymore.

After some major construction on Canal Street in 1989, the monument was moved temporarily. It was then put in a less noticeable place. The words on it were changed to say "in honor of those Americans on both sides of the conflict." In July 2015, New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu suggested removing the monument completely. In December 2015, the New Orleans City Council voted to remove it. They also voted to remove three other statues that were seen as causing problems. The monument was finally removed on April 24, 2017. Workers removed it with police protection because of threats from people who supported the monument.