James Longstreet facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Longstreet

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| United States Minister to the Ottoman Empire | |

| In office December 14, 1880 – April 29, 1881 |

|

| President | |

| Preceded by | Horace Maynard |

| Succeeded by | Lew Wallace |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 8, 1821 Edgefield District, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | January 2, 1904 (aged 82) Gainesville, Georgia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Alta Vista Cemetery, Gainesville, Georgia, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses |

Maria Louisa Garland

(m. 1848–1889)Helen Dortch

(m. 1897) |

| Alma mater | United States Military Academy Class of 1842 |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank |

|

| Unit |

|

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

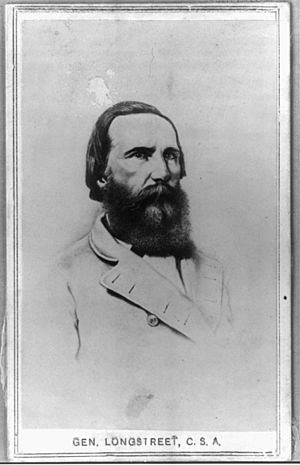

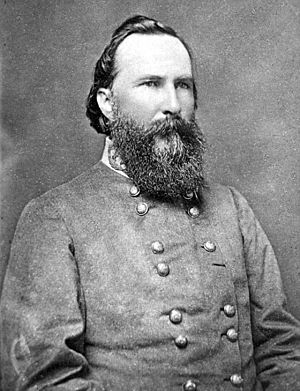

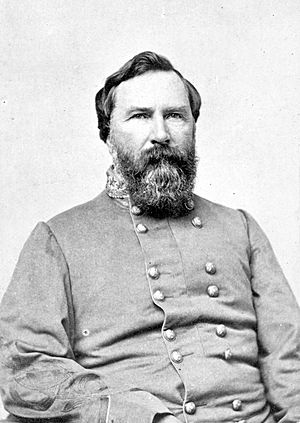

James Longstreet (born January 8, 1821 – died January 2, 1904) was a very important Confederate general during the American Civil War. He was the main helper to General Robert E. Lee, who even called him his "Old War Horse". Longstreet led a large group of soldiers, called a corps, for most of the battles fought by Lee's army. He also fought for a short time in the Western part of the war.

After finishing school at West Point, Longstreet served in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War. He was hurt in a battle and later married his first wife, Louise Garland. In 1861, Longstreet left the U.S. Army to join the Confederate Army. He led Confederate troops to an early win at Blackburn's Ford. He also played a small part in the First Battle of Bull Run.

Longstreet helped a lot in many big Confederate victories. He was one of Robert E. Lee's main helpers. He made a mistake at Seven Pines by marching his men the wrong way. But he was very important in the Seven Days Battles in 1862. Here, he helped lead attacks that pushed the Union army away from Richmond, the Confederate capital. Longstreet led a strong counterattack that made the Union army retreat at Second Bull Run. His soldiers held their ground well in battles like Antietam and Fredericksburg. He was not at the big Confederate win at Chancellorsville. This was because he and his soldiers were busy with a smaller fight called the Siege of Suffolk.

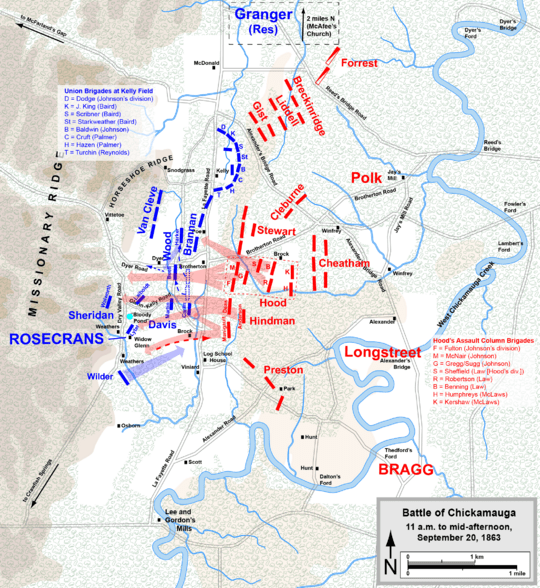

Longstreet's most talked-about service was at the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863. He did not agree with General Lee's plans for how to fight. He sadly led several attacks that did not work. After this, Longstreet went to the Western part of the war to fight under General Braxton Bragg. His troops made a fierce attack at Chickamauga and won the day. But his leadership during the Knoxville campaign led to a Confederate loss. Longstreet had many disagreements with other Confederate generals. He and his men then went back to Lee. He led troops well at the Battle of the Wilderness in 1864. Here, he was badly hurt by friendly fire (meaning his own side accidentally shot him). He later came back to fight, serving under Lee during the Siege of Petersburg and the Appomattox campaign.

After the war, Longstreet had a good career working for the U.S. government. He was a diplomat and a public servant. He supported the Republican Party and worked with his old friend, President Ulysses S. Grant. He also wrote some critical comments about Lee's performance during the war. This made many of his old Confederate friends dislike him. His standing in the South got even worse when he led African-American soldiers against a group called the White League in 1874. This group was against the Reconstruction efforts. Some writers blamed Longstreet for the South losing the Civil War, especially for his actions at Gettysburg. When he was an old man, he married Helen Dortch Longstreet, who was much younger than him. She worked hard to improve his image after he died. Since the late 1900s, many historians have started to see Longstreet in a better light. Many now think he was one of the war's most skilled commanders.

Contents

- Early Life and Military Beginnings

- Mexican-American War Experience

- Life After the Mexican-American War

- American Civil War Service

- Post-War Life and Legacy

- Later Years and Passing

- Historical View and Memorials

- See also

Early Life and Military Beginnings

Boyhood and Family

James Longstreet was born on January 8, 1821. This was in the Edgefield District, South Carolina. This area is now part of North Augusta. He was the fifth child of James Longstreet and Mary Ann Dent. His parents owned a cotton farm near where Gainesville is today. James's family came from Dutch and English backgrounds. His father called him "Peter" because he was strong and steady. People called him Pete or Old Pete for the rest of his life.

James's father wanted him to have a military career. He sent James to live with his aunt and uncle, Frances Eliza and Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, in Augusta, Georgia. James stayed on his uncle's farm, Westover, for eight years. He went to the Academy of Richmond County. His father died in 1833 from a sickness. James stayed with his uncle, even though his mother moved to Somerville, Alabama.

As a boy, James loved swimming, hunting, fishing, and riding horses. He became very good at shooting. Northern Georgia was a wild place when he was young. This meant James sometimes had rough manners. He dressed simply and used strong language, but not around women. Longstreet later said his aunt and uncle were very kind. He didn't seem interested in politics before the war. But his uncle Augustus was a lawyer and supported states' rights. James probably heard these ideas. His uncle also taught him to play cards.

West Point and Early Army Service

In 1837, James's uncle tried to get him into the United States Military Academy. But there was no spot for him. The next year, a relative helped him get in. Longstreet was not a good student. He said he cared more about soldier training and sports than school.

He was in the bottom third of his class in every subject. He almost failed a mechanics exam. He also got many demerits for things like messy rooms and long hair. One of his teachers was Dennis Hart Mahan. Mahan taught about quick movements and smart troop placement. Longstreet used these ideas later in the Civil War.

Longstreet was popular with his classmates. He became friends with many future Civil War leaders. These included Ulysses S. Grant, who would become a U.S. President. Longstreet finished 54th out of 56 cadets in 1842. He became a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army.

After school, Longstreet was stationed in Missouri. He met his future wife, Maria Louisa Garland, there. His friend Grant also met Longstreet's cousin, Julia Dent, and they married. Longstreet attended Grant's wedding. Later, Longstreet was sent to Louisiana and Florida. He was promoted to first lieutenant in 1845. He then moved to Corpus Christi, Texas.

Mexican-American War Experience

Longstreet fought well in the Mexican–American War. He was a lieutenant in the 8th U.S. Infantry. He fought in battles like Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma in 1846. He led a counterattack at the Battle of Monterrey, pushing back Mexican soldiers.

In 1847, he was promoted to first lieutenant. He then joined General Winfield Scott's army to attack Mexico City. Longstreet fought in the Battle of Churubusco. He carried the army flag under heavy fire. He was promoted to captain for his bravery. He was also promoted to major for the Battle of Molino del Rey. At the Battle of Chapultepec on September 12, he was shot in the leg while carrying the flag. He gave the flag to his friend, Lt. Pickett, who reached the top of the hill. The capture of Chapultepec led to Mexico City falling. Longstreet slowly got better from his wound.

Life After the Mexican-American War

After the war, James Longstreet married Maria Louisa Garland on March 8, 1848. They had 10 children, but only five lived to be adults. Longstreet rarely wrote about his family life. He was a very devoted family man.

Longstreet worked in New York and Pennsylvania. In 1850, he became the Chief Commissary for the Department of Texas. This job meant he bought and gave out food to soldiers and animals. It was a lot of paperwork. He wanted a higher-paying job to support his family. He asked to join the cavalry, but his request was denied.

He then served in Texas, protecting towns from Native Americans. He often went on scouting trips. His family lived in San Antonio. In 1854, he moved to Fort Bliss in El Paso, and his family joined him. He fought against the Mescalero people in 1855.

In 1858, Longstreet asked to be moved to the East. He wanted his children to get a better education. He was made a major and paymaster in Kansas. He left his son Garland at a school in New York. He later moved to New Mexico as a paymaster. His wife and children joined him there.

Not much is known about Longstreet's life before the Civil War. He didn't keep a diary. His memoirs mostly talk about his war service. A fire in 1889 destroyed many of his personal papers.

American Civil War Service

Joining the Confederacy

When the American Civil War started, Longstreet was still in the U.S. Army. He was stationed in New Mexico. After hearing about the Battle of Fort Sumter, he decided to join the South. He said it was a "sad day" to leave the U.S. Army. He felt he had to follow his home state.

Longstreet was not excited about the South leaving the Union. But he believed in states' rights. He felt he had to support his homeland. He was born in South Carolina and grew up in Georgia. But he offered his service to Alabama, which had helped him get into West Point. He was the highest-ranking West Point graduate from Alabama. This meant he could lead Alabama soldiers.

He officially left the U.S. Army on May 9, 1861. He had already joined the Confederate States Army on May 1. His U.S. Army resignation was accepted on June 1.

Longstreet went to Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital. On June 22, 1861, he met with Confederate President Jefferson Davis. He was made a brigadier general on June 17. He was sent to Manassas. There, he took command of a group of three Virginia regiments.

Longstreet trained his soldiers very hard. His group first fought at Blackburn's Ford on July 18. They fought against Union troops. Longstreet's men were pushed back at first. He rode forward to stop them from breaking. Other Confederate soldiers arrived and helped. The Union troops then pulled back.

This battle happened before the First Battle of Bull Run. In the main battle on July 21, Longstreet's group was under artillery fire for nine hours. But they played a small part in the actual fighting. After the Union army was defeated, Longstreet wanted to chase them. But his commanders told him to retreat. He was very angry. He said, "Retreat! Hell, the Federal army has broken to pieces."

On October 7, Longstreet was promoted to major general. He took command of a larger group of soldiers. This group was part of the new Army of Northern Virginia.

Personal Tragedy

On January 10, 1862, Longstreet went to Richmond. He talked about creating a draft for soldiers. He spent time with his wife, Louise, and their children. He went back to the army on January 20. But then he got a telegram. It said all four of his children were very sick with scarlet fever. Longstreet rushed back to Richmond.

He arrived before his one-year-old daughter, Mary Anne, died on January 25. His four-year-old son, James, died the next day. Eleven-year-old Augustus Baldwin died on February 1. His 13-year-old son, Garland, was still sick but got better. Longstreet and his wife did not go to the funerals. Longstreet went back to the army on February 5. He rushed back again when Garland got worse, but Garland recovered. These losses deeply affected Longstreet. He became quiet and less social. Before this, his headquarters were known for parties. Afterward, it became much more serious. He rarely drank and became more religious.

Peninsula Campaign Battles

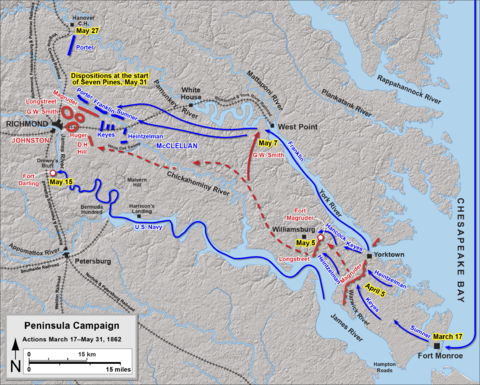

In the spring of 1862, Union General George B. McClellan launched the Peninsula campaign. He wanted to capture Richmond. Longstreet's group helped protect the army's retreat. They fought hard at the Battle of Williamsburg on May 5. Longstreet launched a counterattack that pushed Union soldiers back. This battle helped protect Confederate supply wagons. It also slowed down McClellan's army.

On May 31, during the Battle of Seven Pines, Longstreet made a mistake. He marched his men the wrong way. This caused confusion and delays. Only a small part of his soldiers reached the battle. General Johnston was wounded. Robert E. Lee then took command of the Army of Northern Virginia. Longstreet later said he wasn't sure Lee was ready to lead.

In late June, Lee planned to push McClellan away from Richmond. This led to the Seven Days Battles. On June 27, at Gaines's Mill, Longstreet's fresh soldiers joined the fight. They charged the Union lines and made them retreat. Longstreet fought again on June 30 at Glendale. He spread his troops out, which some historians think cost him the battle. Other Confederate leaders were too slow to help. McClellan was able to move his army to Malvern Hill.

At the Battle of Malvern Hill the next day, Longstreet's men were attacked from the sides. They had to pull back. Longstreet was in charge of almost half of Lee's army during these battles. He fought aggressively and well. Lee's army had problems with maps and organization. Other generals, even Stonewall Jackson, didn't do their best. But they pushed the Union army back. Longstreet's chief of staff said he was "like a rock in steadiness" in battle. General Lee called him "the staff in my right hand." Longstreet became Lee's main helper. Lee then made Longstreet's command much bigger. Longstreet became good friends with Lee.

After the campaign, a newspaper article gave all the credit for Glendale to another general. Longstreet wrote a letter to correct it. The other general, A.P. Hill, got angry. He asked to be moved out of Longstreet's command. Longstreet agreed. Hill then refused to give Longstreet information and was arrested. He even challenged Longstreet to a duel. Lee stepped in and moved Hill's soldiers to Jackson's command.

Second Bull Run Success

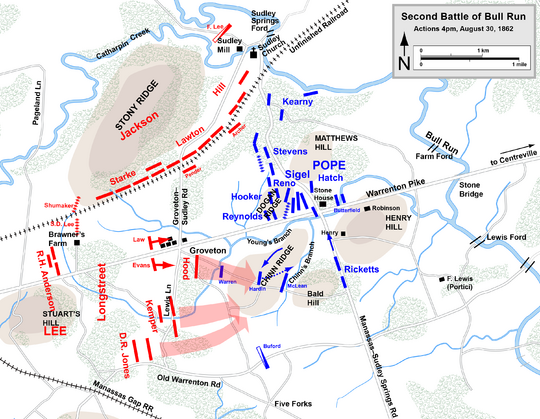

Stonewall Jackson was known for daring attacks. Longstreet was known for strong defense. But in the Northern Virginia campaign of August 1862, this changed. The U.S. government created a new army. General John Pope was in charge. Pope moved south to attack Lee. Lee sent Jackson to stop Pope. Jackson won a big battle at Battle of Cedar Mountain. Lee then ordered Longstreet north too.

Longstreet's men started marching on August 17. On August 23, Longstreet had a small fight with Pope's army. Meanwhile, Confederate cavalry rode around Pope's army. They captured soldiers and supplies.

Jackson made a wide move and captured Pope's main supply base. He then took a strong defensive spot. Pope attacked Jackson. Longstreet and the rest of the army marched to join the battle. On August 28, Longstreet fought a Union group at the Battle of Thoroughfare Gap. Longstreet's men marched about 30 miles in a little over 24 hours. This allowed him to join Lee's army. Some people later said Longstreet marched too slowly. But he covered the distance quickly.

When Longstreet arrived on August 29, Lee wanted him to attack the Union army's side. Longstreet suggested waiting. He wanted to check the ground first. This was done, and it showed Union soldiers were in front of them. Longstreet's soldiers moved forward and pushed back Union troops. But they had to pull back at night. Some people criticized Longstreet for being slow and not wanting to attack. But a Union general later said that if Longstreet had attacked then, his side would have lost many men.

The next day, August 30, was one of Longstreet's best days. Pope thought Jackson was retreating. He ordered his soldiers to chase Jackson. But they ran into Jackson's men and suffered many losses. This left the Union army's left side open. Longstreet saw this chance. He launched a huge attack with over 25,000 men. For over four hours, they hit the Union side like a "giant hammer." Longstreet directed the artillery fire himself.

The Union troops fought hard. But Pope's army had to retreat, just like at the First Bull Run. Longstreet gave all the credit to Lee. He called the campaign "clever and brilliant." This battle showed Longstreet's idea of using strong defense with a smart attack. On September 1, Jackson's men tried to cut off the Union retreat. Longstreet's men stayed behind to make Pope think Lee's whole army was still there.

Antietam Defense

After the win at Second Manassas, Lee decided to take the war into Maryland. He hoped this would help Virginia and get foreign countries to help the Confederacy. Longstreet supported this plan. His men crossed into Maryland on September 6.

At the Battle of Antietam on September 17, the Union general, McClellan, attacked in small parts. He didn't use all his soldiers at once. In the morning, fighting was heavy on the Confederate left. Longstreet's men held their ground in the center. They defended a sunken road. This spot was very strong. Longstreet sent more soldiers to help. Union troops tried to break through, but the Confederate lines held.

Later in the afternoon, Union soldiers tried to cross a creek. Confederate soldiers defended the heights. For hours, Union troops tried and failed to cross. Finally, they managed to cross. But then, more Confederate soldiers arrived. Fighting continued until dark. This was the bloodiest single day of the Civil War. At the end of the day, Lee called Longstreet his "old war-horse!" Lee's army stayed at Antietam until September 18. Then they went back into Virginia.

On October 9, Longstreet was promoted to lieutenant general. Lee made sure Longstreet's promotion was dated one day before Jackson's. This made Longstreet the highest-ranking lieutenant general in Lee's army. In November, Longstreet's command was named the First Corps. It had about 41,000 men.

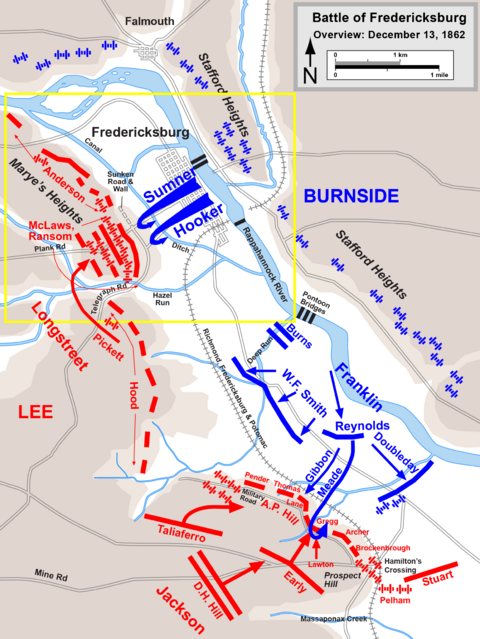

Fredericksburg Victory

After a quiet time, Union General Burnside moved his army towards Fredericksburg, Virginia. Longstreet marched his men there to meet him. Longstreet arrived early. This allowed him to build strong defenses. He ordered trenches and barriers to be built along a stone wall at the base of Marye's Heights.

Burnside tried to cross the river on December 11. Confederate soldiers fought hard from inside Fredericksburg. Burnside then bombed the town. By the next day, his army had crossed and taken Fredericksburg.

Longstreet's men were strongly dug in along Marye's Heights. On December 13, Union troops attacked Longstreet's position. The first attack was a huge failure. It caused about 1,000 losses in 30 minutes. Longstreet told Lee that as long as he had enough bullets, he would "kill them all." He was right. His soldiers easily pushed back several more attacks. In some places, Confederate soldiers were four or five deep behind the stone wall. They loaded rifles for each other. This made their firing almost constant.

One Union general said the scene was like "a great slaughter pen." He said his men "might as well have tried to take Hell." Longstreet's troops had about 1,900 losses. Burnside's army lost over 12,000 men. Most of these were in front of Marye's Heights. An artillery officer called Fredericksburg "the easiest battle we ever fought."

Suffolk Campaign

In October 1862, Longstreet had suggested going to fight in the Western part of the war. After Fredericksburg, he suggested it again. He wanted his soldiers to go help the Army of Tennessee. The Confederate army was low on food. Southern Virginia had a lot of food. Lee sent two of Longstreet's groups to Richmond. Then Longstreet himself was told to take command of these groups. He was also in charge of North Carolina and Southern Virginia.

In March, Longstreet's men mainly looked for food in Virginia and North Carolina. Longstreet sent some soldiers to help capture a town in North Carolina. This failed, but they got a lot of supplies. In April, Longstreet surrounded Union forces in Suffolk, Virginia. There was little fighting.

At the end of April, Longstreet was ordered to join Lee's army. Lee was facing an attack at the Battle of Chancellorsville. Longstreet moved his groups north, but he couldn't get there in time. Longstreet's food-gathering trips got enough food for Lee's whole army for two months. But his absence meant 15,000 soldiers were not at Chancellorsville. Some people later said he could have gotten back in time. But his staff said it was "humanly impossible" to move faster.

Gettysburg Challenges

Planning the Campaign

After Chancellorsville, Longstreet and Lee met in May. They talked about plans for the summer. Longstreet again wanted to send his soldiers to Tennessee. He thought this would help stop the Union army from taking Vicksburg. He believed a stronger army in Tennessee could push back the Union. Lee disagreed. He wanted to invade Pennsylvania. This would take pressure off Virginia. It would also threaten a U.S. city and make people in the North less supportive of the war.

Longstreet's own writings about this meeting were written years later. They might be affected by what happened and by later criticisms. But in his report after the battle, Lee wrote that they "had not been intended to fight a general battle... unless attacked."

After Jackson died, Lee reorganized his army. Longstreet's First Corps lost one group of soldiers. He was left with three groups. Longstreet sent a scout to gather information. The scout told Longstreet that the Union army was moving faster than expected. They were already near Frederick, Maryland. This made Lee order his army to gather near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The scout also said that a new general, Meade, was in charge of the Union army.

July 1–2 at Gettysburg

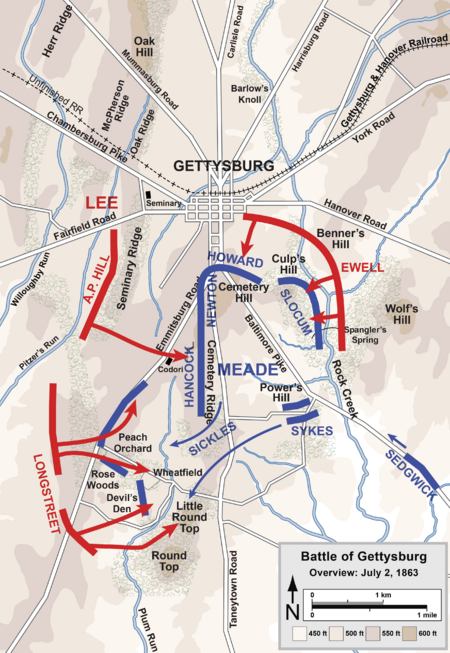

Longstreet arrived at Gettysburg on the afternoon of July 1. His soldiers were still hours away. Lee had not planned to fight until his whole army was there. But fighting started anyway. The first day was a big Confederate win. Union soldiers were pushed back through the town to high ground.

Longstreet met with Lee. He was worried about how strong the Union position was on the high ground. He suggested moving around the Union army's left side. This would make the Union attack them. But Lee said, "If the enemy is there tomorrow, I will attack him." Longstreet replied, "If he is there tomorrow it is because he wants you to attack." Lee was excited by his army's success. He refused Longstreet's idea. Longstreet then suggested an immediate attack. But Lee wanted to wait for more soldiers to arrive.

Lee's plan for July 2 was for Longstreet to attack the Union's left side. Then other generals would attack the center and right. Longstreet again argued for moving around the Union side. But Lee said no. Longstreet was not ready to attack as early as Lee wanted. He waited for more of his soldiers to arrive. They had marched 28 miles in eleven hours. But they didn't get there until noon.

Longstreet's soldiers had to take a long detour to reach their positions. This was because of bad scouting. Some people later said Longstreet was ordered to attack early in the morning. They said his delays caused the loss. But Lee's staff said this was not true. Lee agreed to the delays. He didn't give his formal attack order until 11 AM. Longstreet did not rush to follow Lee's orders. His staff said he seemed slow. While Lee expected an attack around noon, Longstreet was not ready until 4 PM. This gave the Union more time to bring in soldiers.

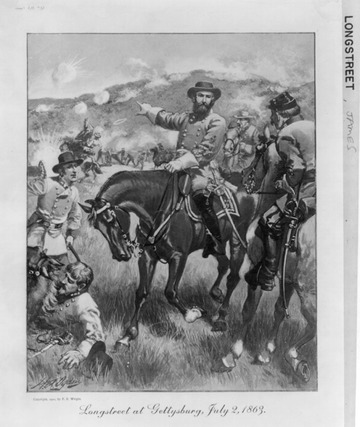

When the attack started around 4 PM, Longstreet pushed his men hard. He personally led the attack on horseback. A Union general, Daniel Sickles, had moved his men forward to an exposed spot. Longstreet's soldiers attacked Sickles's men. After very heavy fighting, they pushed them back. But Union reinforcements stopped the Confederates. General Hood was wounded. Two other generals were badly hurt. One of Longstreet's groups tried to take Little Round Top, a hill on the Union left. But Union soldiers had already fortified it. The attacks failed. Longstreet's soldiers lost over 4,000 men. His attacks did not happen at the same time as other Confederate attacks. This allowed the Union to move soldiers to stop him.

July 3 and Pickett's Charge

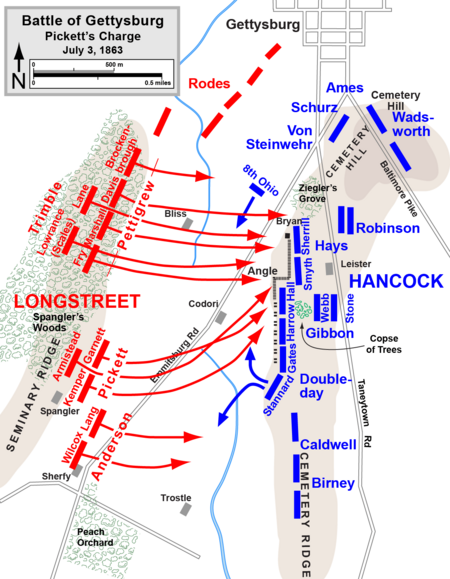

On the night of July 2, Longstreet did not meet Lee. He said he was too tired. He spent the night planning to move around a hill to attack the Union from behind. But he didn't know that many Union soldiers were there to block this move. Lee joined Longstreet at sunrise. Lee was upset. No one had ordered Longstreet's soldiers forward. Longstreet had been planning his own attack without talking to Lee. Lee wrote later that Longstreet's plans were "not completed as early as was expected."

Lee's plans for an early attack were now impossible. Instead, Lee ordered Longstreet to lead a huge attack on the center of the Union line. This was at Cemetery Ridge. Longstreet strongly felt this attack would fail. He told Lee his worries. The Confederates would have to march almost a mile across open ground. They would also have to cross fences under fire. Longstreet urged Lee not to use all his soldiers. He said they were tired from the day before. Lee agreed. He decided to use about 14,000 or 15,000 men. Longstreet again told Lee he thought the attack would fail.

Lee did not change his mind. Longstreet then agreed. The plan was to have a huge artillery attack first. Then, soldiers would lead the attack. Longstreet oversaw the positioning of his men. But he did not check on another general's soldiers carefully enough. This other general had never led so many men. His soldiers had also lost many men the day before. This left Longstreet's men vulnerable. Longstreet and this general had a difficult relationship.

Longstreet was very worried about the attack. He tried to give the order to another officer. The artillery attack began around 1 PM. Both sides fired cannons for almost two hours. When it was time to order the soldiers forward, Longstreet could only nod. He couldn't speak the order. This began the attack known as Pickett's Charge.

The attack started around 3 PM. Confederate soldiers marched towards the Union lines. As Longstreet had thought, the attack was a disaster. The Confederates were easily shot down. They suffered huge losses. Many generals were wounded or killed. One group briefly broke through the Union lines. But they were pushed back. Lee told his men, "It is all my fault." Longstreet's staff said Lee later regretted not taking Longstreet's advice. On July 4, the Confederate army began to retreat from Gettysburg.

Chickamauga and Tennessee Campaigns

In August 1863, Longstreet again tried to move to the Western part of the war. He wrote to a Confederate official. He wanted to serve under his old friend Joseph Johnston. Lee and President Davis agreed on September 5. Longstreet's soldiers traveled over 16 railroads to reach General Bragg in northern Georgia. The trip took over three weeks.

On September 19, at the Battle of Chickamauga, Bragg tried to get his army between the Union army and a city. Longstreet's soldiers fought well. When Longstreet arrived on the field that evening, he had trouble finding Bragg's headquarters. He and his staff almost got captured.

When they finally met, Bragg put Longstreet in charge of the left side of his army. Bragg planned an attack for September 20. Longstreet lined up his men in two lines. He put one group of soldiers in a column to act as shock troops. The attack was supposed to start early. But confusion caused delays. Longstreet's attack didn't start until after 11 AM.

A mistake by the Union general caused a gap in their line. Longstreet took advantage of this. His soldiers poured through the gap. They pushed the Union forces back. The Union right side completely fell apart. The Union general fled. Another Union general, George Henry Thomas, managed to rally the retreating soldiers. He set up a strong defense on a hill. He held this position against Longstreet's attacks. Bragg did not fully support Longstreet. This kept the Union army from being completely defeated. Thomas managed to get his soldiers to Chattanooga, Tennessee. Bragg did not chase them. He said he lacked transportation. But Chickamauga was the biggest Confederate win in the West. Longstreet got a lot of credit for it.

Conflicts in Tennessee

After Chickamauga, Longstreet argued with Bragg. He became a leader of generals who wanted Bragg removed. Longstreet wrote that Bragg "was incompetent to manage an army." President Davis came to settle the arguments. Bragg stayed in command.

Bragg then punished the generals who spoke against him. He reduced Longstreet's command. Longstreet learned he had a new son, named Robert Lee. A new Union general, Grant, arrived in Chattanooga.

Longstreet's relationships with his own officers also got worse. He had been friends with one general, McLaws. But McLaws criticized Longstreet's actions at Gettysburg. Longstreet also accused McLaws of being slow after Chickamauga. Longstreet favored another general, Jenkins, to lead a division. But the soldiers preferred another general, Law.

Union troops managed to open a supply line. Longstreet's soldiers failed to take it back. Longstreet blamed some of his officers. Longstreet then planned to move most of Bragg's army to attack a Union railhead. President Davis approved. But Bragg disagreed. Bragg then sent Longstreet and his men to East Tennessee. They were to fight Union General Burnside. This started the Knoxville campaign.

Longstreet was criticized for moving slowly towards Knoxville. Some soldiers called him "Peter the Slow." At the Battle of Campbell's Station, Union soldiers escaped Longstreet's troops. This was partly due to one of Longstreet's officers. The Confederates also had bad roads and few supplies.

Burnside dug in around Knoxville. Longstreet surrounded the city. Longstreet learned that Bragg had been defeated at Chattanooga. He decided to attack Burnside's defenses before Union reinforcements arrived. On November 29, he attacked at the Battle of Fort Sanders. The attack failed. Longstreet had to retreat. When Bragg was defeated, Longstreet was ordered to join him. But Longstreet refused. He started moving back to Virginia. He fought a battle at Bean's Station on December 14. Then the armies settled for winter. Longstreet's second independent command was a failure. He blamed others. He removed McLaws from command. He also asked to resign, but his request was denied.

The Confederate soldiers suffered greatly that winter. Longstreet's men had little shelter or food. Many had no shoes. In February 1864, Longstreet's men returned to Lee's army in Virginia.

Wilderness to Appomattox

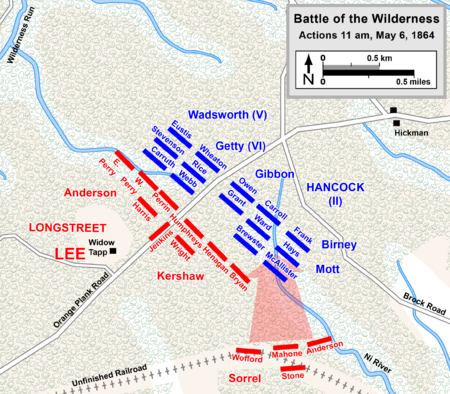

In March, Longstreet rejoined Lee's army. He learned that his old friend Ulysses S. Grant was now the main Union general. Longstreet told his officers that Grant "will fight us every day and every hour until the end of the war."

Longstreet helped save the Confederate Army at the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864. Grant attacked Lee on May 5. The fighting was not clear. The next morning, Union soldiers attacked hard. They pushed back Confederate troops. Just then, Longstreet's men arrived. They used an old railroad bed to move unseen. Then they launched a powerful attack from the side.

Longstreet's men pushed back the Union soldiers. He used smart tactics for the difficult land. He ordered his men to advance in lines that fired constantly. A historian said Longstreet showed "tactical genius." After the war, a Union general told Longstreet, "You rolled me up like a wet blanket."

During this attack, Longstreet was accidentally shot by his own side. This happened near where Stonewall Jackson was also accidentally shot a year earlier. The bullet went through his shoulder and neck. Another general riding with Longstreet was also shot and died. The attack slowed down. As he was carried off, Longstreet urged Lee to keep attacking. But Lee delayed, giving the Union time to regroup. The next attack failed. Some believe that if Longstreet hadn't been hurt, the Union army would have retreated.

Longstreet missed the rest of the 1864 campaigns. Lee missed his skill. Without him, the Confederate army fought Grant. They were then surrounded by Union forces at Petersburg. Longstreet returned in October 1864. His right arm was paralyzed. He had to learn to write with his left hand. He slowly got the use of his right hand back. For the rest of the Siege of Petersburg, Longstreet commanded the defenses near Richmond. He retreated with Lee in the Appomattox campaign. He commanded two corps after another general died.

As Lee's army tried to escape, Longstreet fought at Battle of Sailor's Creek on April 6. The Confederates lost many men. By April 7, Lee's army was much smaller. Some Confederate officers wanted Lee to surrender. They asked Longstreet to talk to Lee. But he refused. He said, "If General Lee doesn't know when to surrender until I tell him, he will never know." Lee was already talking to Grant about surrender.

Lee held his last war meeting on April 8. They decided Longstreet would hold back Union troops. Another general would lead an escape. At the Battle of Appomattox Court House that morning, Longstreet fought hard. But the other general's troops were surrounded. Longstreet could not send help. Lee had no choice but to meet Grant to surrender.

Lee worried that Grant would demand harsh terms. Longstreet told him he believed Grant would be fair. As Lee rode to surrender, Longstreet told him to break off the meeting if Grant was too demanding. After Lee surrendered, Longstreet met Grant. Grant greeted him warmly. He offered Longstreet a cigar. Longstreet said Grant's greeting was "as though nothing had ever happened to mar our pleasant relations."

Post-War Life and Legacy

On June 7, 1865, Longstreet and other former Confederate officers were accused of treason. This was a serious crime. But Grant objected. He told President Andrew Johnson that the men were protected by the surrender terms. Grant threatened to resign. Johnson backed down. The legal challenges against Longstreet were dropped.

After the war, Longstreet and his family moved to New Orleans. He started a cotton business. He also became president of an insurance company. He tried to get other business jobs but was not always successful. With Grant's help, he asked for a pardon from President Johnson. But Johnson refused. He told Longstreet that he, Jefferson Davis, and Robert E. Lee could never get a pardon. He said Longstreet had caused too much trouble for the Union.

Longstreet publicly asked Southerners to accept Reconstruction. He wanted them to follow federal laws. This included laws ending slavery and giving citizenship to black people. He told white Southerners to join the Republican Party. He argued that if they didn't, black people would control the party in the South. In June 1868, a law gave pardons to many former Confederate officers, including Longstreet.

Longstreet joined the Republicans. He supported Grant for president in 1868. Grant then appointed him as a customs officer in New Orleans. This job paid well. Many white Southerners disliked him for this. They called him a "traitor." One old friend called him a "scalawag." Longstreet did not back down. He supported the Republican governor of Louisiana. In 1870, he was made a general in the Louisiana State Militia. In 1872, he was put in charge of all militia and police in New Orleans. He then resigned his other jobs.

Writers who supported the "Lost Cause" movement attacked Longstreet. This movement praised the South and criticized Reconstruction. They blamed Longstreet for the loss at Gettysburg. These attacks started in 1872. One general said Longstreet attacked late at Gettysburg. Another said Longstreet disobeyed an order to attack at sunrise. This "sunrise order" was not true.

In 1873, Longstreet sent police to a town in Louisiana. They were to help the local government against white supremacists. But they arrived after a terrible event where many black people were killed. In 1874, there were protests in New Orleans about election problems. A group of white supremacists attacked the State House. Longstreet led a force of police and African-American soldiers. He rode to meet the protesters but was pulled from his horse and captured. The white supremacists charged, and many of Longstreet's men fled. Federal troops had to be sent in to restore order. Longstreet's use of armed black soldiers made anti-Reconstructionists even angrier.

In 1875, Longstreet started to defend his war record. He asked for proof from his critics. But the accusations had already ruined his reputation in the South. Longstreet wrote articles defending himself. At the same time, he became popular in the North. They liked his support for Reconstruction and his praise for Grant. He often gave speeches in the North. He was well received by Union veterans. In 1886, he went to a ceremony in Atlanta. He was greeted warmly by Jefferson Davis and the crowd.

In 1875, the Longstreet family moved back to Gainesville, Georgia. Louise had given birth to ten children, five of whom lived. Longstreet continued to work for the city school board. In 1877, he became a Catholic. He remained a strong believer.

Later Years and Passing

Longstreet worked for the U.S. government under President Rutherford B. Hayes. He was briefly a deputy tax collector and postmaster. In 1880, President Hayes made Longstreet the U.S. ambassador to the Ottoman Empire (modern-day Turkey). He served from December 1880 to April 1881. Living in Constantinople was expensive. He couldn't bring his family. His only known success was convincing the Sultan to let American archaeologists do research.

Longstreet served as a U.S. Marshal in Georgia from 1881 to 1884. But when a new president was elected, his political career ended. He retired to a farm near Gainesville. He raised turkeys and grew crops. A fire in 1889 destroyed his house and many personal items. That December, his first wife, Louise, died.

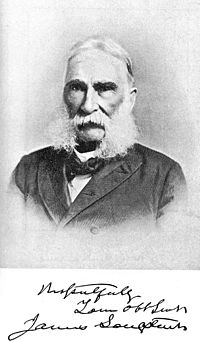

After Louise's death, Longstreet wrote his memoirs, From Manassas to Appomattox. It took him five years to write. It was published in 1896. In the book, Longstreet praised some Civil War officers. But he often criticized others, especially those who attacked him after the war. He showed affection for Robert E. Lee but sometimes criticized his strategy. The book did not change the minds of his critics.

Longstreet served as U.S. Commissioner of Railroads from 1897 to 1904. In 1897, at age 76, he married Helen Dortch. She was 34. Longstreet's children did not like the marriage. But Helen became a very devoted wife. She worked hard to improve his image after he died. She lived 58 years longer than him. In 1898, Longstreet, then 77, wanted to lead U.S. troops in Cuba.

Longstreet's last years were marked by poor health. He was partly deaf. He had severe pain in 1902. His weight dropped a lot. He had cancer in his right eye. He died in Gainesville on January 2, 1904, six days before his 83rd birthday. He was buried in Alta Vista Cemetery in Gainesville. He lived longer than most of his critics. He was one of the few Civil War generals to live into the 1900s.

Historical View and Memorials

Longstreet was strongly criticized for his war record. This started in the 1870s and continued after his death. His widow, Helen, wrote a book defending him. She said people were wrongly taught that Longstreet's actions caused the Confederate loss. His reputation was badly damaged for many years.

In the early 1900s, a famous historian, Douglas Southall Freeman, kept the criticism of Longstreet alive. He said Longstreet was slow at Gettysburg. He even wondered why Lee didn't arrest him. But later, Freeman changed his views a bit. He said Longstreet's "attitude was wrong but his instinct was correct."

In 1974, a novel called The Killer Angels was published. It was about Gettysburg and based on Longstreet's memoirs. In 1993, it was made into a movie, Gettysburg. Longstreet was shown in a very good way in both. This greatly improved how people saw him.

Many modern historians now think Longstreet was a very skilled commander. One historian called him "the finest corps commander" in Lee's army. He said Longstreet was "arguably the best corps commander in the conflict on either side." Another historian noted that Longstreet had the best staff of any commander.

People today praise Longstreet for his actions after the war. He was willing to work with the North. He supported voting rights for black people. He was brave in leading a mixed-race militia to stop white supremacists.

Longstreet is remembered in his hometown of Gainesville, Georgia. There is a bridge named after him. There is also a local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

In 1998, a statue of Longstreet was put up at Gettysburg National Military Park. It shows him riding his horse, Hero. It is at ground level, unlike most generals' statues.

Longstreet's Billet is a house in Russellville, Tennessee. Longstreet stayed there in the winter of 1863–64. It is now The Longstreet Museum and is open to the public.

-

Painting of Longstreet at Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park

See also

In Spanish: James Longstreet para niños

In Spanish: James Longstreet para niños