James A. Garfield facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

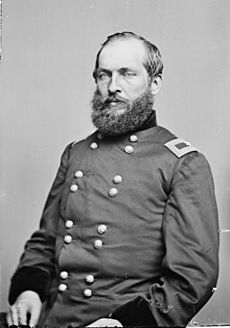

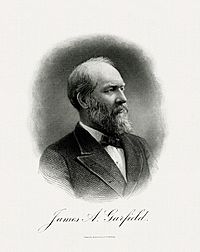

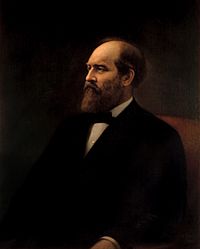

James A. Garfield

|

|

|---|---|

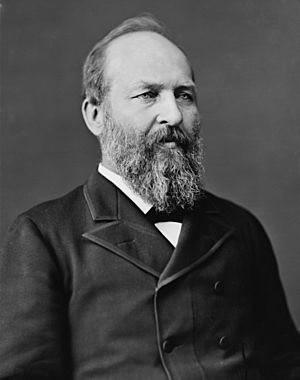

Garfield in 1881

|

|

| 20th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1881 – September 19, 1881 |

|

| Vice President | Chester A. Arthur |

| Preceded by | Rutherford B. Hayes |

| Succeeded by | Chester A. Arthur |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 19th district |

|

| In office March 4, 1863 – November 8, 1880 |

|

| Preceded by | Albert G. Riddle |

| Succeeded by | Ezra B. Taylor |

| Chair of the House Appropriations Committee | |

| In office March 4, 1871 – March 4, 1875 |

|

| Preceded by | Henry L. Dawes |

| Succeeded by | Samuel J. Randall |

| Member of the Ohio Senate from the 26th district |

|

| In office January 2, 1860 – August 21, 1861 |

|

| Preceded by | George P. Ashmun |

| Succeeded by | Lucius V. Bierce |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

James Abram Garfield

November 19, 1831 Moreland Hills, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | September 19, 1881 (aged 49) Elberon, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | James A. Garfield Memorial |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 7, including Hal, James, and Abram |

| Education |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1863 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | |

James Abram Garfield (born November 19, 1831 – died September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States. He served as president for only six months, from March 4, 1881, until his death. He was shot by an assassin named Charles J. Guiteau and passed away two months later.

Before becoming president, Garfield was a lawyer and a general in the American Civil War. He also served nine terms in the United States House of Representatives. He is the only person to be elected president while still serving in the House of Representatives.

Contents

James A. Garfield: From Log Cabin to White House

Early Life and Family

James Abram Garfield was born on November 19, 1831. He was the youngest of five children. His parents were Abram Garfield and Eliza Ballou. His family was very poor and lived in a simple log cabin in Orange Township, Cuyahoga County, Ohio. This area is now known as Moreland Hills, Ohio.

James's father died in 1833, when James was very young. His strong mother raised him and his siblings in poverty. James was his mother's favorite child, and they stayed close throughout his life. He loved hearing her stories about his family history, especially about his Welsh ancestors.

Garfield later shared that he wished he hadn't been born into poverty. He felt that his first 17 years were a "chaos of childhood." He believed that a boy with a father and more money might have learned "manly ways" earlier.

Education and Marriage

From 1848 to 1850, Garfield attended Geauga Seminary. Here, he finally had time to study academic subjects he had missed. Geauga was a school for both boys and girls. James met Lucretia Rudolph there, and they later married in 1858. They had seven children together, but only five lived past infancy.

After Geauga, Garfield worked for a year, including teaching jobs. From 1851 to 1854, he went to the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute in Hiram, Ohio. This school was run by the Disciples religious group. He loved studying Greek and Latin, but he was eager to learn about anything new. He even worked as a janitor and then became a teacher while still a student.

By 1854, Garfield had learned everything the Institute could teach him. He became a full-time teacher there. Then, he enrolled at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. He started as a third-year student because of his studies at the Institute.

Garfield graduated with honors from Williams College in August 1856. He was named the second-best student in his class and gave a speech at the graduation ceremony.

Early Career in Politics

After returning to Ohio, Garfield studied law and became an attorney. In 1859, he was elected as a Republican to the Ohio State Senate. He served there until 1861.

Serving in the Civil War

When Abraham Lincoln became president, several Southern states left the Union. They formed a new government called the Confederate States of America. Garfield read many military books, waiting for the war to begin. He saw the war as a fight against slavery. In April 1861, the rebels attacked Fort Sumter, starting the American Civil War. Even though Garfield had no military training, he felt he needed to join the Union Army.

He quickly rose through the ranks and became a major general. He fought in important battles like Middle Creek, Shiloh, and Chickamauga.

Life in Congress

In 1862, Garfield was elected to Congress to represent Ohio's 19th district. During his time in Congress, he strongly supported the gold standard. He also became known as a very skilled speaker. Garfield was a strong supporter of black suffrage, which meant giving African Americans the right to vote.

He celebrated when the 15th Amendment was approved in 1870. This amendment gave African Americans the right to vote. Garfield believed this amendment gave the "African race the care of its own destiny." He also wanted Georgia to rejoin the Union quickly.

In 1871, Congress discussed the Ku Klux Klan Act. This law was meant to stop attacks on African Americans' voting rights. Garfield found this law difficult to decide on. He was angry at the Klan, calling them "terrorists."

During the Civil War, taxes on imported goods (tariffs) were very high. After the war, Garfield studied money matters closely. He wanted to move towards free trade, which means fewer taxes on goods from other countries.

In 1870, Garfield became the head of the House Banking Committee. He led an investigation into the "Black Friday" Gold Panic scandal. His investigation showed that paper money (greenbacks) had helped cause the problem.

Presidency (1881)

In the 1880 presidential election, Garfield ran a quiet campaign from his home. He won the election by a small margin against Winfield Scott Hancock.

Financial and Government Changes

Garfield told his Secretary of the Treasury, William Windom, to refinance the national debt. This meant calling back old U.S. bonds that paid 6% interest. People who owned these bonds could get cash or new bonds that paid 3% interest. This saved taxpayers about $10 million. To compare, the government spent less than $261 million in 1881.

Presidents Grant and Hayes had both wanted to reform the civil service. By 1881, groups pushing for these reforms were very active. Garfield agreed with them. He believed the "spoils system" (giving jobs to friends or supporters) hurt the presidency. It often made people ignore more important issues. Some reformers were disappointed when Garfield only made small changes. He also gave jobs to some of his old friends.

There was also a lot of corruption in the post office. In 1880, Congress investigated the Post Office Department. There were reports that groups were stealing millions of dollars. They would get mail contracts for a low price, then raise the costs and share the extra money. Soon after becoming president, Garfield heard about this corruption. He learned that Assistant Postmaster General Thomas J. Brady was involved.

Garfield demanded Brady's resignation and ordered that he be charged. He wanted the corruption "rooted out to the bone," no matter who was involved. Brady resigned and was charged with conspiracy. However, juries found Brady not guilty in 1882 and 1883.

Civil Rights and Education

Garfield believed that government-supported education was key to improving civil rights for African Americans. After the Civil War, formerly enslaved people (freedmen) gained citizenship and the right to vote. This allowed them to take part in government. But Garfield worried that their rights were being taken away by white people in the South. He also worried about illiteracy (not being able to read or write). He feared that Black Americans would become a permanent "peasantry" (poor farmers).

He suggested a "universal" education system paid for by the federal government. In 1866, Garfield helped write a bill for a National Department of Education. They hoped that facts and figures would convince Congress to create a federal agency for school reform. But Congress and many white people in the North lost interest in African-American rights. So, Congress did not pass federal funding for universal education during Garfield's time as president.

Garfield did work to appoint several African Americans to important government jobs. These included Frederick Douglass and John Mercer Langston. Garfield believed that Southern support for the Republican Party could come from business interests, not just race issues. He started to change President Hayes's policy of trying to please Southern Democrats.

Garfield didn't have much experience with foreign policy. So, he relied a lot on his Secretary of State, James G. Blaine. They both wanted to promote freer trade, especially in the Western Hemisphere. Garfield and Blaine thought that increasing trade with Latin America would stop the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from controlling the region. They also believed that more exports would make America more prosperous.

Garfield allowed Blaine to plan a Pan-American conference for 1882. This meeting would help settle disagreements among Latin American nations. It would also be a place to discuss increasing trade.

They also hoped to help end the War of the Pacific. This war was being fought by Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. Blaine wanted a solution where Peru would not lose any land. But by 1881, Chile had taken over Peru's capital, Lima. Chile refused any agreement that would return things to how they were before.

Garfield also wanted to expand America's influence in other areas. He wanted to change the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty. This would allow the United States to build a canal through Panama without British involvement. He also tried to reduce British influence in the important Kingdom of Hawaii. Garfield and Blaine even had plans for the U.S. to be involved beyond the Western Hemisphere. They wanted trade agreements with Korea and Madagascar.

Garfield also thought about making the U.S. military stronger overseas. He asked Navy Secretary Hunt to look into the navy's condition. He wanted to expand and modernize it. In the end, these big plans didn't happen because Garfield was assassinated. Nine countries had agreed to come to the Pan-American conference. But the invitations were canceled in April 1882 after Blaine left the cabinet. Arthur, Garfield's successor, also canceled the conference. Naval improvements continued under Arthur, but on a smaller scale than Garfield and Hunt had planned.

Assassination

The Shooting

Charles J. Guiteau had tried many different jobs. In 1880, he decided to get a government job by supporting the Republican Party. He wrote a speech called "Garfield vs. Hancock." The Republican National Committee printed it. At that time, people would give speeches to convince voters. But Guiteau was not a famous speaker, so he didn't get many chances to speak. One time, he couldn't even finish his speech because he was too nervous.

Guiteau believed his small contribution helped Garfield win. He thought he deserved to be appointed as a consul in Paris. This was despite the fact that he didn't speak French or any other foreign language. One medical expert later described Guiteau as possibly having narcissistic schizophrenia. Another expert called him a clinical psychopath.

One of Garfield's tiring duties was meeting people who wanted jobs. He met Guiteau at least once. White House officials told Guiteau to talk to Secretary Blaine, as the consul job was in the State Department. Blaine also met with the public often, and Guiteau became a regular visitor. Blaine had no plans to give Guiteau a job he wasn't qualified for. He simply said that a delay in the Senate made it impossible to consider the Paris consulship.

Guiteau started to believe he didn't get the job because of political disagreements within the Republican Party. He decided that the only way to end these disagreements was for Garfield to die. He had nothing personal against the president. He thought that if Arthur became president, it would bring peace and reward people like him.

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln was seen as a rare event during the Civil War. Garfield, like most people, didn't think the president needed guards. His plans were often printed in newspapers. Guiteau knew Garfield would leave Washington for a cooler place on July 2, 1881. He planned to kill him before then. He bought a gun that he thought would look good in a museum. He followed Garfield several times, but each time his plans failed, or he lost his courage. He had only one chance left: Garfield's train departure on the morning of July 2.

Guiteau hid near the ladies' waiting room at the Sixth Street Station. Garfield was scheduled to leave from there. Most of Garfield's cabinet planned to go with him for part of the trip. Blaine, who was staying in Washington, came to see him off. The two men were talking deeply and didn't see Guiteau. He pulled out his gun and shot Garfield. Guiteau tried to leave the station but was quickly caught. As Blaine recognized him, Guiteau was led away. He said, "I did it. I will go to jail for it. I am a Stalwart and Arthur will be President." News of his reason for the shooting made many people angry at his political group.

Guiteau was charged with the president's murder on October 14, 1881. During his trial, Guiteau said he wasn't responsible for Garfield's death. He admitted to shooting him but not to killing him. The trial was chaotic, with Guiteau often interrupting. His lawyers tried to use an insanity defense. The jury found him guilty on January 25, 1882. He was sentenced to death by hanging and was executed on June 30, 1882.

Funeral and Memorials

Garfield's funeral train left Long Branch on the same special track that brought him there. The tracks were covered with flowers, and houses had flags. His body was taken to the Capitol and then to Cleveland for burial. The Marine Band leader, John Philip Sousa, wrote a march called "In Memoriam" for Garfield. It was played when Garfield's body arrived in Washington, D.C.

More than 70,000 people waited for hours to see Garfield's coffin. His body was displayed from September 21 to 23, 1881, at the United States Capitol rotunda. On September 25, in Cleveland, Garfield's casket was paraded down Euclid Avenue. Former presidents Grant and Hayes, and Generals William Sherman and Sheridan were there. More than 150,000 people paid their respects. Sousa's march was played again. Garfield's body was first placed in the Schofield family vault in Cleveland's Lake View Cemetery. This was until his permanent memorial was built.

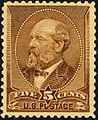

Memorials to Garfield were built across the country. On April 10, 1882, the U.S. Post Office Department issued a postage stamp in his honor. In 1884, a sculptor named Frank Happersberger finished a monument in San Francisco. In 1887, the James A. Garfield Monument was dedicated in Washington. Another monument was put up in Philadelphia's Fairmount Park in 1896.

On May 19, 1890, Garfield's body was permanently placed in a mausoleum at Lake View Cemetery. Former President Hayes, President Benjamin Harrison, and future president William McKinley attended the ceremony. Harrison said Garfield was always a "student and instructor." He believed Garfield's life and death would "continue to be instructive and inspiring." The monument shows Garfield as a teacher, a Union major general, and a speaker. It also shows him taking the presidential oath and his body lying in state.

Garfield's murder by a disturbed person made the public realize the need for civil service reform. Senator George H. Pendleton started an effort that led to the Pendleton Act in January 1883. This act changed the "spoils system." Before, people paid or gave political help to get government jobs. Under the new act, jobs were given based on merit and competitive exams. Congress and President Arthur created the Civil Service Commission to make sure the reform happened. The Pendleton Act, however, only covered 10% of federal workers. For Arthur, who was known for the "spoils system," this reform became his most important achievement.

A marble statue of Garfield by Charles Niehaus was added to the National Statuary Hall Collection in the Capitol in Washington D.C. This was a gift from the State of Ohio in 1886.

Garfield is also honored with a bronze sculpture inside the Cuyahoga County Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument in Cleveland, Ohio.

On March 2, 2019, the National Park Service put up exhibit panels in Washington. These panels mark the spot where he was assassinated.

Legacy and Historical View

For some years after his assassination, Garfield's life story was seen as a great example of the American dream. It showed that even the poorest boy could become President of the United States.

Garfield's presidency started with great promise before it ended too soon. Historian Justus D. Doenecke notes his achievements. He says Garfield "enhanced both the power and prestige of his office." As a person, he was "intelligent, sensitive, and alert." His knowledge of how government worked was "unmatched."

Interesting Facts About James A. Garfield

- James was named after his older brother, who died as a baby.

- Because he was poor and had no father, other kids sometimes made fun of Garfield. He found comfort in reading many books.

- Garfield left home at age 16 in 1847. He found work on a canal boat, managing the mules that pulled it.

- Garfield was an excellent student. He was especially interested in languages and public speaking.

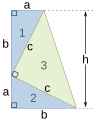

- Garfield was very good at mathematics. He even created a famous proof of the Pythagorean theorem. He published it in 1876. A math historian called his work "really a very clever proof."

- Garfield strongly supported the abolition of slavery. He even thought about taking away Southern plantations. He also considered exiling or executing rebel leaders to make sure slavery ended forever.

- Garfield didn't think Lincoln was very worthy of being reelected at first. He thought, "He will probably be the man, though I think we could do better." In later years, Garfield praised Lincoln more. A year after Lincoln's death, Garfield called him "Greatest among all these developments." In 1878, he called Lincoln "one of the few great rulers whose wisdom increased with his power."

James A. Garfield Quotes

- “Things don’t turn up in this world until somebody turns them up.”

- “The men who succeed best in public life are those who take the risk of standing by their own convictions.”

- “Next in importance to freedom and justice is popular education, without which neither freedom nor justice can be permanently maintained.”

- “I mean to make myself a man, and if I succeed in that, I shall succeed in everything else.”

- “Be fit for more than the thing you are now doing. Let everyone know that you have a reserve in yourself,— that you have more power than you are now using. If you are not too large for the place you occupy, you are too small for it.”

- “The chief duty of government is to keep the peace and stand out of the sunshine of the people.”

- “I would rather be beaten in Right than succeed in Wrong.”

Images for kids

-

General William S. Rosecrans

-

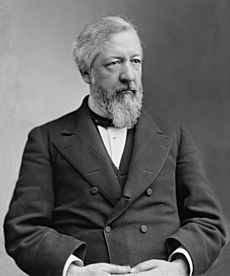

Salmon P. Chase was Garfield's ally until Andrew Johnson's impeachment trial.

-

Garfield Monument, by the Capitol, where he served almost twenty years

-

President U.S. GrantMathew Brady 1870

-

Editorial cartoon: Uncle Sam directs U.S. Senators and Representatives implicated in the Crédit Mobilier scheme to commit Hara-Kiri.

-

Garfield (second from right in the row of commissioners just below the gallery) served on the Electoral Commission that decided the disputed 1876 presidential election. Painting by Cornelia Adele Strong Fassett.

-

Following Grant's defeat for the nomination Puck magazine satirized Robert E. Lee's surrender to him at Appomattox by depicting Grant giving up his sword to Garfield.

-

Lawnfield, Garfield National Historic Site, location of the "front porch campaign"

-

Garfield Memorial at Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio

-

James A. Garfield Monument in Washington, D.C.

See also

In Spanish: James A. Garfield para niños

In Spanish: James A. Garfield para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |