James G. Blaine facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James G. Blaine

|

|

|---|---|

Blaine c. 1870s

|

|

| 28th and 31st United States Secretary of State | |

| In office March 9, 1889 – June 4, 1892 |

|

| President | Benjamin Harrison |

| Preceded by | Thomas F. Bayard |

| Succeeded by | John W. Foster |

| In office March 7, 1881 – December 19, 1881 |

|

| President | James A. Garfield Chester A. Arthur |

| Preceded by | William M. Evarts |

| Succeeded by | Frederick T. Frelinghuysen |

| United States Senator from Maine |

|

| In office July 10, 1876 – March 5, 1881 |

|

| Preceded by | Lot M. Morrill |

| Succeeded by | William P. Frye |

| 27th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 3, 1875 |

|

| Preceded by | Theodore Pomeroy |

| Succeeded by | Michael C. Kerr |

| Leader of the House Republican Conference | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 3, 1875 |

|

| Preceded by | Theodore M. Pomeroy |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Brackett Reed |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Maine's 3rd district |

|

| In office March 4, 1863 – July 10, 1876 |

|

| Preceded by | Samuel C. Fessenden |

| Succeeded by | Edwin Flye |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

James Gillespie Blaine

January 31, 1830 West Brownsville, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | January 27, 1893 (aged 62) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Blaine Memorial Park, Augusta, Maine |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Harriet Stanwood |

| Children | 7, including Walker |

| Education | Washington and Jefferson College (BA) |

| Signature | |

James Gillespie Blaine (born January 31, 1830 – died January 27, 1893) was an important American politician. He was a member of the Republican Party. Blaine represented the state of Maine in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876. During this time, he served as the Speaker of the House from 1869 to 1875. Later, he was a U.S. Senator from 1876 to 1881.

Contents

Early Life and Education

James Gillespie Blaine was born on January 31, 1830, in West Brownsville, Pennsylvania. He was the third child of Ephraim Lyon Blaine and Maria Gillespie Blaine. His father was a successful businessman and landowner. The family lived a comfortable life. James's mother's family were Irish Catholics who came to Pennsylvania in the 1780s.

People who wrote about Blaine say he had a happy childhood. He loved history and books from a young age. When he was thirteen, Blaine went to Washington College (now Washington & Jefferson College). He was a good student and graduated near the top of his class in 1847. After college, he thought about studying law, but decided to look for a job instead.

Teacher and Newspaper Editor

In 1848, Blaine became a math and language teacher at the Western Military Institute in Georgetown, Kentucky. He was only 18, but he did well in his new job. There, he met Harriet Stanwood, a teacher from Maine. They got married on June 30, 1850.

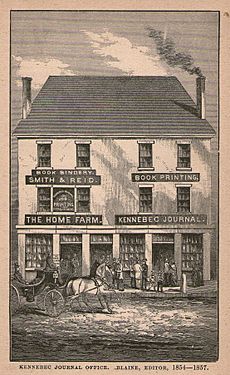

After teaching, Blaine and his wife moved to Philadelphia. In 1853, he got an exciting offer to become an editor and part-owner of the Kennebec Journal newspaper in Maine. He borrowed money from his wife's brothers and took the job. This decision was a big step towards his long career in politics. The newspaper was very successful, and Blaine used his earnings to invest in coal mines, which helped him become wealthy.

Political Career

Blaine's work as a Republican newspaper editor naturally led him into politics. He strongly supported Abraham Lincoln and the Union during the American Civil War. In 1858, Blaine was elected to the Maine House of Representatives. He was re-elected several times. Because of his new political duties, he stopped working as an editor in 1860.

Blaine was known as "the Magnetic Man" because he was a very good speaker. In March 1869, he was chosen to be the Speaker of the House. He easily won the election for Speaker. He was re-elected Speaker for two more terms. His time as Speaker ended in 1875 when the Democratic Party gained control of the House.

As Speaker, Blaine was very effective and popular. President Ulysses S. Grant valued his leadership. Blaine enjoyed his job and bought a large home in Washington, D.C. His family also moved to a mansion in Augusta, Maine.

Blaine's popularity grew during his six years as Speaker. Some Republicans even thought he should run for president in 1872. However, Blaine supported President Grant's re-election instead. As he became more famous, he also faced more criticism. In 1872, he was accused of taking bribes in a scandal. Blaine denied any wrongdoing, and no clear proof of corruption was ever found. However, these accusations caused problems for his presidential campaign later on.

Serving in the Senate

Blaine became a U.S. Senator for Maine on July 10, 1876. He served on important committees, but he did not have the same leadership role he had in the House.

During his time in the Senate, Blaine developed his ideas about foreign policy. He wanted to make the American navy and merchant marine stronger. These had become weaker since the Civil War. He also disagreed with a decision that gave Great Britain money related to American fishing rights in Canadian waters. Blaine supported high tariffs (taxes on imported goods). He later changed his mind about a trade agreement with Canada, believing that increasing American exports was more important.

Secretary of State

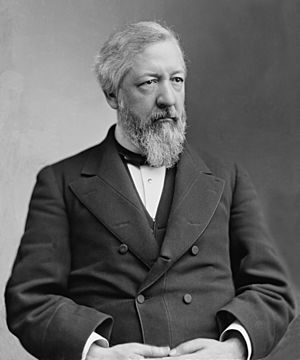

Blaine served as Secretary of State twice. This is the top diplomat for the country. First, he served in 1881 under Presidents James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur. Then, he served again from 1889 to 1892 under President Benjamin Harrison. He is one of only two people to hold this job under three different presidents.

Diplomacy in the Pacific

Blaine wanted to expand American trade and influence across the Pacific Ocean. He was especially interested in getting rights to harbors in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and Pago Pago, Samoa.

When Blaine became Secretary of State, the United States, Great Britain, and Germany were arguing over their rights in Samoa. Blaine helped arrange a meeting in Berlin to solve the problem. The countries agreed to share access to the harbor.

In Hawaii, Blaine worked to bring the kingdom closer to the United States. He wanted to prevent it from becoming a British territory. Blaine suggested that Hawaii become an American protectorate, which means the U.S. would protect it. The Hawaiian king, Kalākaua, did not want to give up his country's independence. Blaine then appointed his friend, John L. Stevens, as minister to Hawaii. Stevens believed the U.S. should take over Hawaii. He worked with Americans living there to make this happen. These efforts later led to a revolt against Hawaii's queen in 1893. Blaine was no longer in office when this happened.

Latin America and Trade

Blaine also wanted to bring together countries in the Western Hemisphere. He organized the First International Conference of American States in Washington in 1890. Blaine hoped for closer trade and political ties, including a common market and a way to settle disputes. He publicly said he only wanted to "annex trade," not land. However, he privately mentioned wanting to gain Hawaii, Cuba, and Puerto Rico.

Congress was not as excited about a common market. But, new tariff rules were added that lowered taxes on some trade between American countries. The conference did not achieve all of Blaine's goals right away. However, it led to more communication and eventually the Organization of American States.

In 1891, a problem arose with Chile. The American minister in Chile, Patrick Egan, gave safety to Chileans seeking refuge during a civil war. This made Chile suspicious of Blaine. Later, American sailors from the Baltimore ship got into a fight in Chile, and two sailors died. President Harrison demanded payment from Chile. Blaine tried to calm things down and offered to settle the dispute peacefully. Chile eventually apologized, and the threat of war ended.

Retirement and Death

Blaine often felt his health was not strong. By the time he joined President Harrison's team, he was truly unwell. He also faced personal sadness. Two of his children died in 1890, and another son died in 1892.

Because of his health and family losses, Blaine decided to retire. He announced he would leave his job on June 4, 1892. This was just before the Republican Party meeting to choose a presidential candidate. President Harrison thought Blaine might be planning to run against him.

Harrison was not very popular. Many of Blaine's old supporters encouraged him to run for president. Blaine had said he was not interested months before. But some friends thought he was just being modest and worked to get him nominated. When Blaine resigned, his supporters were sure he would run. However, the party mostly supported Harrison. Harrison was chosen again, but Blaine still received many votes.

Blaine spent the summer of 1892 resting. He did not get involved much in the presidential campaign. Harrison lost the election. Blaine's health quickly got worse in late 1892. He died at his home in Washington on January 27, 1893, just before his 63rd birthday. He was buried in Washington, D.C., and later re-buried in Augusta, Maine.

Legacy

James G. Blaine was a very important figure in the Republican Party during his time. However, he became less well-known after his death. He is the only one of the nine Republican presidential candidates from 1860 to 1912 who never became president.

Historians have studied Blaine's foreign policy work. While he was a powerful politician, his place in history is not as widely remembered as some other figures.

Images for kids

-

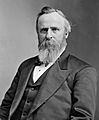

Exposition Hall of Cincinnati during the announcement of Rutherford B. Hayes as the Republican nominee.

-

Blaine worked with President Hayes (pictured) at times.

-

The Interstate Exposition Building (known as the "Glass Palace") during the convention; James A. Garfield is on the podium.

-

Blaine, Benjamin Harrison, and Henry Cabot Lodge with their families on vacation.

-

1890 political cartoon showing Blaine "outplaying" British Prime Minister Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury.

See Also

In Spanish: James G. Blaine para niños

In Spanish: James G. Blaine para niños