William Rosecrans facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William S. Rosecrans

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from California's 1st district |

|

| In office March 4, 1881 – March 3, 1885 |

|

| Preceded by | Horace Davis |

| Succeeded by | Barclay Henley |

| U.S. Minister to Mexico | |

| In office 1868–1869 |

|

| President | Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | Marcus Otterbourg |

| Succeeded by | Thomas H. Nelson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 6, 1819 Delaware County, Ohio, US |

| Died | March 11, 1898 (aged 78) Redondo Beach, California, US |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Alma mater | United States Military Academy Class of 1842 |

| Nickname | "Old Rosy" |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Branch/service | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1842–1854, 1861–1867 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Army of the Mississippi Army of the Cumberland Department of the Missouri |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

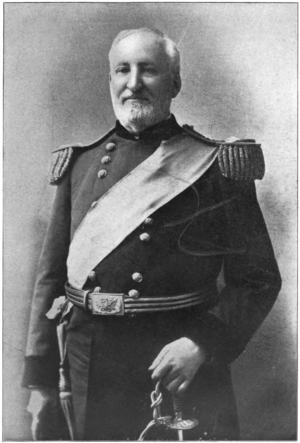

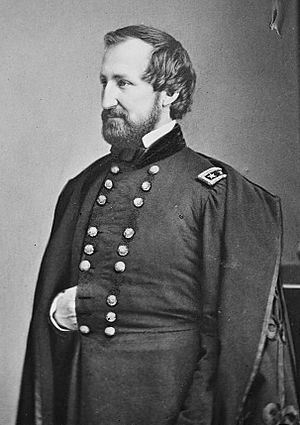

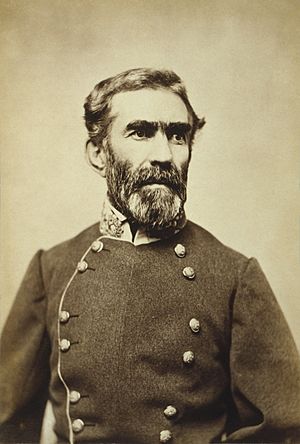

William Starke Rosecrans (September 6, 1819 – March 11, 1898) was an American inventor, business leader, diplomat, and politician. He was also a U.S. Army officer. He became famous as a Union general during the American Civil War. He won important battles in the western part of the war, but his military career ended after a big defeat at the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863.

Rosecrans graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1842. He worked as an engineer and a professor before leaving the Army. He then started a career in civil engineering. When the Civil War began, he led troops from Ohio and had early success in western Virginia. In 1862, he won the battles of Iuka and Corinth. These victories happened while he was working under Major General Ulysses S. Grant.

Rosecrans was known for being direct and sometimes arguing with his bosses. This caused problems with Grant and the Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton. These disagreements affected Rosecrans's career.

Later, he was given command of the Army of the Cumberland. He fought against Confederate General Braxton Bragg at the Battle of Stones River. He then cleverly outmaneuvered Bragg in the amazing Tullahoma Campaign. This forced the Confederates out of Middle Tennessee. His smart moves then made Bragg leave the important city of Chattanooga. However, Rosecrans's pursuit of Bragg ended badly at the bloody Battle of Chickamauga. A confusing order from Rosecrans accidentally created a gap in the Union line. Rosecrans and a large part of his army were forced to retreat. After being surrounded in Chattanooga, Grant removed Rosecrans from command.

After his defeat, Rosecrans was sent to lead the Department of Missouri. There, he stopped Price's Raid. After the war, he worked in diplomacy and politics. In 1880, he was elected to Congress for California.

Contents

Early Life and Education

William Starke Rosecrans was born on a farm in Delaware County, Ohio, on September 6, 1819. He was the second of five sons. His father, Crandall Rosecrans, was a veteran of the War of 1812. Crandall later ran a tavern and a farm. William's middle name came from one of his father's heroes, General John Stark.

William did not have much formal schooling when he was young. He learned a lot by reading books. At 13, he left home to work as a store clerk. He could not afford college, so he tried to get into the United States Military Academy at West Point. He impressed Congressman Alexander Harper, who nominated him.

Rosecrans was very good at his studies at West Point, especially in math. He also excelled in French, drawing, and English. It was there that he got his nickname, "Rosy," or "Old Rosy." He graduated in 1842, ranking fifth in his class of 56 cadets. Many of his classmates became famous generals. He became a brevet second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers. This showed his high academic success. He married Anna Elizabeth Hegeman in 1843. They had eight children together.

Career Journey

After West Point, Rosecrans worked on engineering projects. After a year, he asked to be a professor at West Point. He taught engineering there. In 1845, he changed his religion and became a Catholic. This inspired his youngest brother, Sylvester Horton Rosecrans, to also convert. Sylvester later became the first bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Columbus.

Rosecrans worked on engineering tasks in different cities from 1847 to 1853. During this time, he looked for civilian jobs to support his growing family. He applied for a teaching job at the Virginia Military Institute but lost it to Thomas J. Jackson.

While in Newport, Rhode Island, he helped build St. Mary's Roman Catholic Church. This church is famous as the place where John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Bouvier got married in 1953. There is a special window in the church to honor Rosecrans.

Rosecrans left the Army in 1854 due to health problems. He then started a successful mining business in Western Virginia (now West Virginia). He designed one of the first complete lock and dam systems on the Coal River. In Cincinnati, he and his partners built one of the first oil refineries west of the Allegheny Mountains. He also invented many things, including a better kerosene lamp and a new way to make soap. In 1859, he was badly burned when an experimental oil lamp exploded at his refinery. It took him 18 months to recover. The scars on his face made him look like he was always smirking. The Civil War began as he was recovering.

American Civil War Service

Just after Fort Sumter surrendered, Rosecrans offered to help Ohio Governor William Dennison. He became an aide to Major General George B. McClellan. Rosecrans was promoted to colonel and briefly led the 23rd Ohio Infantry regiment. Two future presidents, Rutherford B. Hayes and William McKinley, were in this regiment. He was then promoted to brigadier general in the regular army in May 1861.

His plans were very effective in the Western Virginia Campaign. His victories at Rich Mountain and Corrick's Ford in July 1861 were some of the first Union wins of the war. However, his boss, General McClellan, got the credit. Rosecrans then stopped Confederate General John B. Floyd and General Robert E. Lee from taking back the area that became West Virginia. When McClellan was called to Washington, he gave Rosecrans command of the Department of Western Virginia.

In late 1861, Rosecrans planned a winter campaign to capture Winchester, Virginia. McClellan did not approve this plan. He also moved many of Rosecrans's troops to another general, leaving Rosecrans with too few men. In March 1862, Rosecrans lost his command when his department was given to General John C. Frémont. He briefly served in Washington, where he disagreed with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton about war tactics. Stanton became one of Rosecrans's biggest critics.

Western Theater Battles

In May 1862, Rosecrans was moved to the Western Theater. He commanded two divisions in Major General John Pope's Army of the Mississippi. He helped in the siege of Corinth. On June 26, he took command of the entire army. He also became responsible for the District of Corinth. In these roles, he reported to Major General Ulysses S. Grant. Grant commanded the District of Western Tennessee.

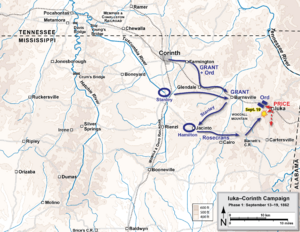

Battle of Iuka

Confederate Major General Sterling Price was ordered to move his army toward Nashville, Tennessee. He was supposed to join General Braxton Bragg's attack in Kentucky. Price's army stopped in Iuka and waited for Major General Earl Van Dorn's army. The two generals wanted to join forces and attack Grant's supply lines.

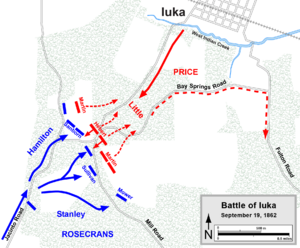

Grant decided to attack Price before Van Dorn could arrive. He sent General Edward Ord with about 8,000 men to approach Iuka from the northwest. Rosecrans's army would march from the southwest to block Price's escape route. Grant was with Ord, so he had little direct control over Rosecrans during the battle.

Rosecrans's army was late because of muddy roads. On September 19, Rosecrans was about two miles from Iuka when his lead troops were suddenly attacked by a Confederate division. The fighting was very intense and lasted until dark. A strong wind blew the sound of the battle away from Ord's position. So, Ord and Grant did not know the battle was happening. Ord's troops stood by while the fight raged nearby.

During the night, Price's forces quietly left. They used a road that the Union army had not blocked. Five days later, Price's army met up with Van Dorn's army. Grant had partly achieved his goal: Price did not join Bragg in Kentucky. But Rosecrans could not destroy Price's army or stop it from joining Van Dorn.

The Battle of Iuka started a long rivalry between Rosecrans and Grant. The newspapers praised Rosecrans more than Grant. Grant's first report praised Rosecrans, but his later reports were more negative.

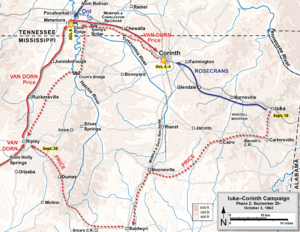

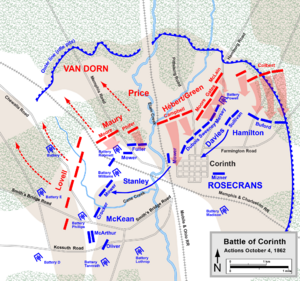

Battle of Corinth

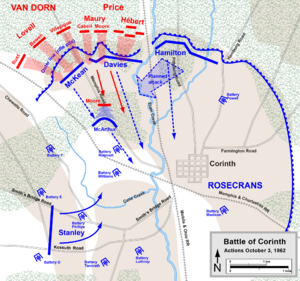

Price's army joined Van Dorn's on September 28. Van Dorn, being the higher-ranking officer, took command. Grant was sure that Corinth was their next target. The Confederates hoped to capture Corinth by surprise. This would cut off Rosecrans from help.

On the morning of October 3, Van Dorn attacked Rosecrans's divisions. The Confederates pushed through a gap in the Union line. The Union forces had to fall back close to their forts. The Confederates had the advantage so far. Rosecrans's army was pushed back at every point. By night, his entire army was inside the forts. Both sides were tired from the fighting. The weather was hot, and water was scarce.

On the second day, October 4, the Confederates attacked again. They faced heavy Union artillery fire. They stormed Battery Powell and Battery Robinett, where there was fierce hand-to-hand fighting. A brief push into Corinth was stopped. After a Union counterattack recaptured Battery Powell, Van Dorn ordered a full retreat. Reinforcements from Grant arrived later, but the battle was already over.

Rosecrans's actions right after the battle were slow. Grant had ordered him to chase Van Dorn right away. But Rosecrans did not start his march until the next morning, October 5. He said his troops needed rest and the thick woods made travel hard. At 1 p.m. on October 4, when chasing the enemy would have been most effective, Rosecrans rode along his line. He wanted to tell his soldiers that rumors of his death were false. At Battery Robinett, he took off his hat and told his soldiers, "I stand in the presence of brave men, and I take my hat off to you."

Leading the Army of the Cumberland

Rosecrans was seen as a hero in the Northern newspapers again. On October 24, he was given command of the Army of the Cumberland. He replaced Major General Don Carlos Buell. Buell had been too slow after the Battle of Perryville. Rosecrans was promoted to major general. Grant was happy that Rosecrans was leaving his command.

As an army commander, Rosecrans became very popular with his soldiers. They called him "Old Rosy" because of his last name and his large red nose. He was a devoted Catholic and carried a crucifix and a rosary. He was known for quickly changing from anger to good humor, which his men liked.

Battle of Stones River

Rosecrans stayed in Nashville for almost two months. He was resupplying his army and training his cavalry. By early December 1862, General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck was impatient. He told Rosecrans, "If you remain one more week in Nashville, I cannot prevent your removal." Rosecrans replied that he knew his duty and was not bothered by threats.

In late December, Rosecrans began his march against Bragg's Army of Tennessee. Bragg's army was camped near Murfreesboro, Tennessee. The Battle of Stones River was one of the bloodiest battles of the war. Both Rosecrans and Bragg planned to attack the other's right side. But Bragg attacked first on December 31. He pushed the Union army back into a small defensive area. Rosecrans showed his energetic style in battle. He personally encouraged his men along the line. He rode back and forth at the very front, even between his soldiers and the enemy.

The armies rested on January 1. But on January 2, Bragg attacked again. This time, he attacked a strong Union position. The Union defense was very strong, and the attack was stopped with heavy losses. Bragg then moved his army to Tullahoma. This meant the Union now controlled Middle Tennessee. This victory was important for Union morale after their defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg. President Abraham Lincoln wrote to Rosecrans, "You gave us a hard-earned victory, which had there been a defeat instead, the nation could scarcely have lived over."

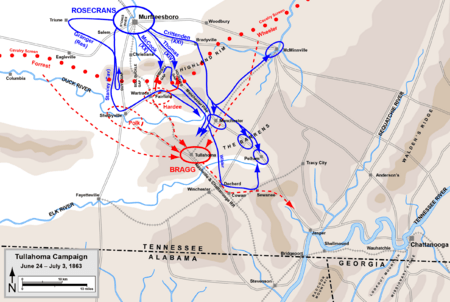

Tullahoma Campaign

Rosecrans kept his army in Murfreesboro for almost six months. He used this time to get supplies and train his troops. He was slow to advance because of the muddy winter roads. President Lincoln, Secretary Stanton, and General Halleck kept asking him to attack Bragg. Rosecrans gave excuses, saying that if he attacked, Bragg might move his army to Mississippi. This would make things harder for Grant's Vicksburg Campaign.

On June 2, Halleck threatened to send some of Rosecrans's troops to Mississippi if he did not move. Rosecrans asked his generals for their opinions. Most of them agreed that an immediate attack was not a good idea. Only his new chief of staff, General James A. Garfield, recommended an immediate advance. On June 16, Halleck sent a direct message: "Is it your intention to make an immediate movement forward? A definite answer, yes or no, is required." Rosecrans replied that he would move in about five days. Seven days later, on June 24, Rosecrans reported that his army was moving against Bragg.

The Tullahoma Campaign (June 24 – July 3, 1863) was a brilliant success. Rosecrans used clever maneuvers and had very few casualties. He forced Bragg to retreat back to Chattanooga. Many historians consider Tullahoma a "brilliant" campaign. Abraham Lincoln called it "the most splendid piece of strategy I know of."

During this campaign, Rosecrans's troops rescued Union spy Pauline Cushman. She had been captured while scouting and was about to be hanged. Her rescue happened just three days before her planned execution. Rosecrans and Cushman later helped raise over a million dollars for soldiers' aid.

Rosecrans did not get as much public praise as he might have. The campaign ended on the same day General Robert E. Lee lost the Battle of Gettysburg. The next day, Vicksburg surrendered to Grant. Secretary Stanton sent Rosecrans a telegram, urging him to "give the finishing blow to the rebellion." Rosecrans was angry. He replied that his army had already driven the Confederates from Middle Tennessee. He asked that the War Department not overlook such a great event.

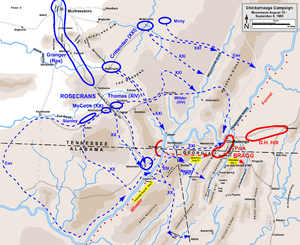

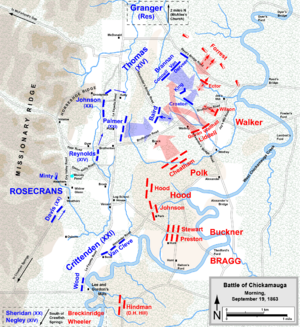

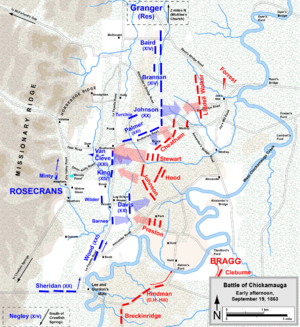

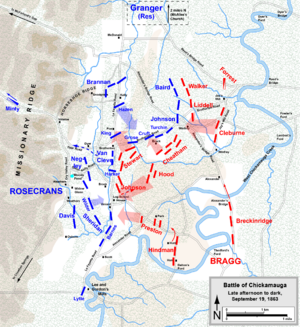

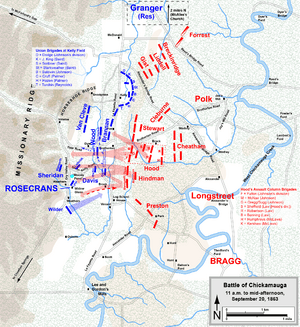

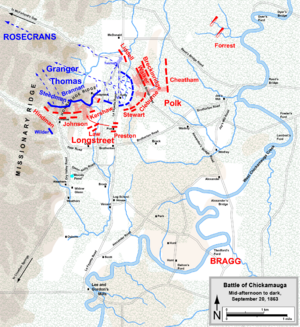

Battle of Chickamauga

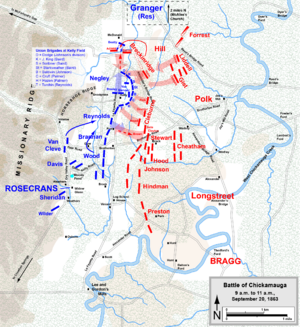

Rosecrans did not immediately chase Bragg after Tullahoma. He took time to regroup and plan how to move through the mountains. When he was ready, he again outmaneuvered Bragg. The Confederates left Chattanooga and went into the mountains of northwestern Georgia. Rosecrans then became too confident, thinking Bragg would keep retreating. He pursued Bragg with his army spread out over three routes. This left his corps commanders dangerously far apart. At the Battle of Davis's Cross Roads on September 11, Bragg almost ambushed and destroyed one of Rosecrans's isolated groups. Rosecrans realized the danger and quickly ordered his army to gather together. The two armies then faced each other across West Chickamauga Creek.

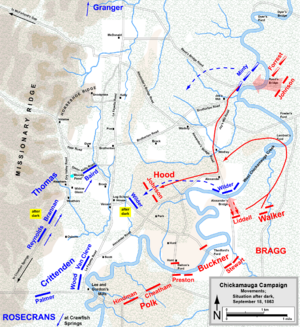

The Battle of Chickamauga began on September 19. Bragg attacked the Union army, which was not fully together yet. But he could not break through Rosecrans's defenses. On the second day, disaster struck Rosecrans. He gave a confusing order to General Thomas J. Wood. Rosecrans wanted Wood to "close up and support [General Joseph J.] Reynolds's [division]," to fill a gap he thought was there. However, Wood's movement actually created a new, large gap in the line. By chance, Confederate General James Longstreet had planned a huge attack in that exact area. The Confederates used this gap to their full advantage, shattering Rosecrans's right side.

Most of the Union units on the right side ran back in confusion toward Chattanooga. Rosecrans, Garfield, and two corps commanders tried to rally the retreating troops. But they soon joined the rush to safety. Rosecrans decided to go quickly to Chattanooga to organize his returning men and the city's defenses. He sent Garfield to Major General George H. Thomas with orders to take command of the remaining forces at Chickamauga and retreat.

The Union army avoided complete disaster because of Thomas's strong defense on Horseshoe Ridge. This heroism earned him the nickname "Rock of Chickamauga." The army retreated that night to fortified positions in Chattanooga. Bragg did not destroy the Army of the Cumberland. But the Battle of Chickamauga was still the worst Union defeat in the Western Theater. Thomas urged Rosecrans to rejoin the army and lead it. But Rosecrans was physically tired and mentally defeated. He stayed in Chattanooga. President Lincoln tried to cheer him up, saying, "Be of good cheer. ... We have unabated confidence in you." But privately, Lincoln said Rosecrans seemed "confused and stunned like a duck hit on the head."

Even though Rosecrans's men were in strong defensive positions, their supply lines into Chattanooga were weak. Confederate cavalry raids often attacked them. Bragg's army surrounded the city and laid siege to the Union forces. Rosecrans, feeling defeated, could not break the siege without more troops. Hours after the defeat, Secretary Stanton ordered Major General Joseph Hooker to go to Chattanooga with 15,000 men. Major General Ulysses S. Grant was ordered to send 20,000 men under Major General William T. Sherman. On September 29, Stanton ordered Grant to go to Chattanooga himself. Grant was given the choice to replace Rosecrans with Thomas. Grant chose Thomas to command the Army of the Cumberland. Grant arrived in Chattanooga on October 23.

Grant carried out a plan that Rosecrans and General William F. "Baldy" Smith had made. This plan opened the "Cracker Line" to resupply the army. In a series of battles for Chattanooga (November 23–25, 1863), Grant defeated Bragg's army and sent it retreating into Georgia.

Missouri Command and Retirement

Rosecrans was sent to Cincinnati to wait for new orders. He did not play a major role in the fighting after that. He commanded the Department of Missouri from January to December 1864. During this time, he helped stop Sterling Price's Missouri raid. In 1864, his former chief of staff, James Garfield, asked Rosecrans if he would consider running as Abraham Lincoln's vice president. Rosecrans replied positively, but Garfield never received the message. Friends of Rosecrans believed that Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton stopped the telegram.

Rosecrans left the U.S. volunteer service on January 15, 1866. On June 30, 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated Rosecrans to be a brevet major general in the regular army. This was to thank him for his actions at Stones River. Rosecrans resigned from the regular army on March 28, 1867. On February 27, 1889, Congress re-appointed him as a brigadier general in the regular army. He was placed on the retired list on March 1, 1889.

After the war, Rosecrans joined the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. This was a society for officers who served in the Union armed forces.

Later Life and Legacy

After the war, Rosecrans became interested in railroads. He was one of the founders of the Southern Pacific Railroad. But he lost his valuable stock in the railroad to dishonest business partners. From 1868 to 1869, Rosecrans served as the U.S. Minister to Mexico. But he was replaced after only five months when his old rival, Ulysses Grant, became president. During this short time, he believed Mexico would benefit from a narrow-gauge railway and telegraph line. But this business venture failed.

Rosecrans then became interested in government. He wrote a book called Popular Government. It suggested reforms for voter registration and voting. Various political parties asked him to run for high office. These included Governor of Ohio and governor of California. He refused all these offers because they conflicted with his business plans. This led to him being called "The Great Decliner."

In 1869, Rosecrans bought 16,000 acres (65 km2) of land in the Los Angeles area. He called it "Rosecrans Rancho." By the time he died, most of the land had been sold off to support his mining investments.

In 1880, Rosecrans was elected as a U.S. Representative from California. In the same year, James Garfield was elected President. Rosecrans was upset because Garfield's campaign highlighted his role in the war at Rosecrans's expense. Their friendship was broken. After Garfield's assassination, letters written by Garfield after Chickamauga were published. These letters may have caused Rosecrans to lose political support at the time.

Rosecrans was reelected in 1882. He became the chairman of the House Military Affairs Committee. In this role, he publicly opposed a bill that would give a pension to former President Grant. Rosecrans objected, saying some of Grant's official statements were false. The bill passed despite his objections. When a bill was introduced in 1889 to restore Rosecrans's rank, some representatives objected because of his actions against Grant. But the bill passed.

Rosecrans did not seek reelection in 1884. He served as a Regent of the University of California in 1884 and 1885.

Rosecrans was sometimes mentioned as a possible presidential candidate. But the first Democratic president elected after the war was Grover Cleveland in 1884. Rosecrans was appointed as the Register of the Treasury, serving from 1885 to 1893.

Rosecrans spoke at a large reunion of veterans (from both the North and South) at the Chickamauga battlefield on September 19, 1889. He gave a moving speech about national healing. This gathering led to Congress creating the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park the next year. This was the nation's first national battlefield park.

In 1896, he received the Laetare Medal. This is a very old and respected award for American Catholics from the University of Notre Dame.

Death and Burial

In February 1898, Rosecrans caught a cold that turned into pneumonia. He seemed to get better. But then he learned that one of his favorite grandchildren had died. He was overcome with sadness, and his health quickly got worse. He died on March 11, 1898, in Redondo Beach, California. His casket was displayed in Los Angeles City Hall. In 1908, his remains were buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Honors and Memorials

Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery, in San Diego, California, is named after him. Major streets named after William Rosecrans include Rosecrans Avenue in Los Angeles County. Rosecrans Street in San Diego runs near the cemetery. A school in Compton, California, and another in Sunbury, Ohio, are named General Rosecrans Elementary. A simple memorial was built at his birthplace in Ohio. It is a large boulder with a plaque, surrounded by a fence. An equestrian statue of him is now in Sunbury, Ohio. Rosecrans' Headquarters before the Chickamauga Campaign was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

The SS Rosecrans was a troop transport ship used in the early 20th century. Another ship, the U.S.A.T. William S. Rosecrans, was built as a Liberty Ship. It was designed to carry 504 troops.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: William S. Rosecrans para niños

In Spanish: William S. Rosecrans para niños

- List of American Civil War generals (Union)

- Fortress Rosecrans