Andrew Johnson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Andrew Johnson

|

|

|---|---|

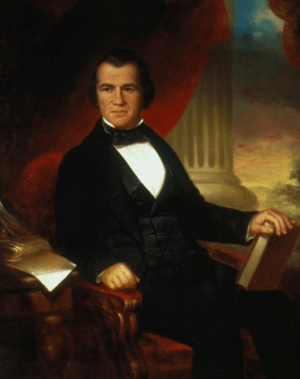

Portrait by Mathew Brady, c. 1870-1875

|

|

| 17th President of the United States | |

| In office April 15, 1865 – March 4, 1869 |

|

| Vice President | None |

| Preceded by | Abraham Lincoln |

| Succeeded by | Ulysses S. Grant |

| 16th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1865 – April 15, 1865 |

|

| President | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | Hannibal Hamlin |

| Succeeded by | Schuyler Colfax |

| United States Senator from Tennessee |

|

| In office March 4, 1875 – July 31, 1875 |

|

| Preceded by | William G. Brownlow |

| Succeeded by | David M. Key |

| In office October 8, 1857 – March 4, 1862 |

|

| Preceded by | James C. Jones |

| Succeeded by | David T. Patterson |

| Military Governor of Tennessee | |

| In office March 12, 1862 – March 4, 1865 |

|

| Appointed by | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | Isham G. Harris (as Governor) |

| Succeeded by | William G. Brownlow (as Governor) |

| 15th Governor of Tennessee | |

| In office October 17, 1853 – November 3, 1857 |

|

| Preceded by | William B. Campbell |

| Succeeded by | Isham G. Harris |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Tennessee's 1st district |

|

| In office March 4, 1843 – March 3, 1853 |

|

| Preceded by | Thomas Dickens Arnold |

| Succeeded by | Brookins Campbell |

| Mayor of Greeneville, Tennessee | |

| In office 1834–1835 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 29, 1808 Raleigh, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | July 31, 1875 (aged 66) Elizabethton, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Stroke |

| Resting place | Andrew Johnson National Cemetery Greeneville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (c. 1839–1864, 1868–1875) |

| Other political affiliations |

National Union (1864–1868) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 5, including Martha |

| Parents |

|

| Profession |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1862–1865 |

| Rank | Brigadier General (as Military Governor of Tennessee) |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808 – July 31, 1875) was the 17th President of the United States. He served from 1865 to 1869. Johnson became president after Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. He was Lincoln's vice president at the time.

Johnson was a member of the Democratic Party. But he ran with Lincoln on the National Union Party ticket. This happened as the Civil War was ending. Johnson wanted the Southern states to rejoin the Union quickly. He did not want special protections for the newly freed people. This caused big disagreements with the Republican-controlled Congress. These conflicts led to his impeachment by the House of Representatives in 1868. He was found not guilty in the Senate by just one vote.

Johnson grew up very poor and never went to school. He learned to be a tailor. He worked in different towns before settling in Greeneville, Tennessee. There, he became an alderman and then mayor. In 1835, he was elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives. After serving in the Tennessee Senate, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1843. He served five terms there. He then became governor of Tennessee for four years. In 1857, the state legislature elected him to the U.S. Senate.

While in Congress, Johnson pushed for the Homestead Bill. This law helped people get land for free if they settled on it. It passed soon after he left the Senate in 1862. When Southern states left the Union to form the Confederate States of America, Johnson stayed loyal. He was the only senator from a Confederate state who did not quit. In 1862, Lincoln made him Military Governor of Tennessee. In 1864, Lincoln chose Johnson as his running mate. This was to show national unity. They won the election.

As president, Johnson started his own plan for Reconstruction. This involved telling Southern states to hold elections and form new governments. But Southern states brought back old leaders. They also passed "Black Codes". These laws took away many rights from freed African Americans. Republicans in Congress refused to let these Southern lawmakers join. They passed laws to undo the Southern actions. Johnson vetoed these bills. But Congress often voted to pass them anyway. This became a pattern for his presidency.

Johnson opposed the Fourteenth Amendment. This amendment gave citizenship to former slaves. In 1866, he went on a national tour to promote his policies. He hoped to stop Republican opposition. As the conflict grew, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act. This law limited Johnson's power to fire Cabinet members. He tried to fire Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. This led to his impeachment by the House. He barely avoided being removed from office by the Senate. He did not win the Democratic presidential nomination in 1868. He left office the next year.

Johnson went back to Tennessee after his presidency. He was elected to the Senate in 1875. This made him the only former president to serve in the Senate. He died five months into his term. Historians often criticize Johnson's strong opposition to federal rights for black Americans. He is usually ranked as one of the worst presidents in U.S. history.

Contents

Andrew Johnson's Early Life

Growing Up Poor

Andrew Johnson was born in Raleigh, North Carolina, on December 29, 1808. His parents were Jacob Johnson and Mary ("Polly") McDonough. His father was a poor man who worked as a town constable. His mother was a laundress. Both of his parents could not read or write. Andrew never went to school and grew up in poverty.

When Andrew was three, his father died. His mother, Polly, had to support the family alone. She apprenticed Andrew to a tailor named James Selby when he was ten. Andrew was legally bound to work for Selby until he was 21. While working, one of Selby's employees taught him to read a little. People would also come to the shop to read aloud to the tailors. This made Johnson love learning. He became a skilled public speaker later in life.

Andrew was not happy working for Selby. After about five years, he and his brother ran away. Selby offered a reward for their return. Andrew worked as a tailor in different towns. He eventually returned to Raleigh, hoping to buy his freedom from his apprenticeship. But he could not agree on terms with Selby. So, he decided to move west.

Moving to Tennessee

Johnson left North Carolina and traveled to Tennessee. He walked most of the way. After a short time in Knoxville, he moved to Mooresville, Alabama. He then worked as a tailor in Columbia, Tennessee. But his mother and stepfather wanted to move west. So, Johnson went back for them.

They traveled through the Blue Ridge Mountains to Greeneville, Tennessee. Johnson loved the town right away. He later bought the land where he first camped there. He planted a tree to remember it.

In Greeneville, Johnson started a successful tailoring business. In 1827, at age 18, he married 16-year-old Eliza McCardle. She was the daughter of a local shoemaker. They were married by a justice of the peace. The Johnsons were married for almost 50 years. They had five children. Eliza was shy and often stayed in Greeneville. She taught Andrew math and helped him improve his writing.

Johnson's tailoring business did well. He hired help and invested in real estate. He was proud of his tailoring skills. He also loved to read. Books about famous speakers made him interested in politics. He would debate with customers in his shop. He also joined debates at Greeneville College.

Johnson and Slavery

In 1843, Andrew Johnson bought his first enslaved person, Dolly, who was 14. Dolly had three children. Soon after, he bought Dolly's half-brother, Sam. Sam and his wife Margaret had nine children. Sam later became a commissioner for the Freedmen's Bureau. He was known for being a proud man. He negotiated with the Johnson family about his work. He even received some money for his labor. In 1867, Andrew Johnson gave him a piece of land for free.

Johnson eventually owned at least ten enslaved people. On August 8, 1863, Andrew Johnson freed his enslaved people. They stayed with him as paid servants. A year later, as military governor, Johnson declared all enslaved people in Tennessee free. Sam and Margaret, his former enslaved people, lived in his tailor shop without paying rent while he was president. As a thank you for freeing them, newly freed people in Tennessee gave Andrew Johnson a watch. It was engraved with "for his Untiring Energy in the Cause of Freedom."

Andrew Johnson's Political Journey

Early Steps in Tennessee

Johnson helped start a "working men's" group in Greeneville in 1829. He was elected as a town alderman. In 1834, he became mayor of Greeneville.

In 1835, Johnson ran for the Tennessee House of Representatives. He won the election. During this time, he also joined the Tennessee Militia. He reached the rank of colonel. People often called him "Colonel Johnson" afterward.

In his first term, Johnson did not always vote with one party. He admired President Andrew Jackson, a Democrat. The major parties were still forming. Johnson opposed government spending and aid for railroads. He lost his re-election in 1837. But he would not lose another election for 30 years. In 1839, he ran again as a Democrat and won. He became a strong supporter of the Democratic Party. He was known for his speeches. People came from everywhere to hear him speak.

In 1840, Johnson was chosen as a presidential elector for Tennessee. This gave him more attention across the state. In 1841, he was elected to the Tennessee Senate. He served a two-year term. He sold his tailoring business to focus on politics. He also bought more land and eight or nine enslaved people.

Serving in the U.S. House of Representatives

After serving in the state legislature, Johnson wanted to be elected to the U.S. Congress. He won the election in 1843. In Washington, he joined the Democratic majority in the House. Johnson spoke for the poor. He was against abolishing slavery. He wanted limited government spending and opposed high tariffs. His wife, Eliza, stayed in Greeneville. Johnson spent his time studying in the Library of Congress instead of attending social events.

Johnson believed the Constitution protected private property, including enslaved people. He thought this meant the government could not end slavery. He won re-election in 1845. He presented himself as a defender of the poor. In his second term, Johnson supported the Mexican War. He opposed the Wilmot Proviso. This was a plan to ban slavery in any new land gained from Mexico. He also introduced his Homestead Bill. This bill would give 160 acres of land to people willing to settle it. This was important to Johnson because of his own humble beginnings.

In the 1848 presidential election, the Democrats split over slavery. Johnson supported the Democratic candidate, Lewis Cass. But the party split helped the Whig candidate, Zachary Taylor, win easily.

Johnson also supported government help for railroads. This was because of national interest in new railroads. His district also needed better transportation.

For his fourth term, Johnson focused on slavery, homesteads, and judicial elections. He won by a large margin in 1849. When Congress met, they struggled to elect a Speaker. Johnson suggested a rule to allow a Speaker to be elected by a simple majority. This idea was later used, and Democrat Howell Cobb was elected.

After the Speaker was chosen, slavery became the main issue. Northerners wanted California to join as a free state. Henry Clay introduced the Compromise of 1850. This plan allowed California to join and passed other laws for both sides. Johnson voted for most parts of the compromise. But he did not vote for ending slavery in Washington, D.C. He also proposed changes to the Constitution. He wanted senators and the president to be elected directly by the people. He also wanted to limit federal judges' terms to 12 years. These ideas were defeated.

Johnson won his fifth term in 1851. His main issue was passing the Homestead Bill. His opponent argued it would help end slavery. Johnson won by over 1600 votes. In 1852, the House passed his Homestead Bill, but it failed in the Senate. The Whigs gained control of the Tennessee legislature. They changed the boundaries of Johnson's district. This made it harder for him to win future elections there.

Governor of Tennessee

Johnson decided to run for governor of Tennessee. The Democratic Party chose him. The Whigs had won the last two governor elections. Johnson debated the Whig candidate, Henry. Johnson won the election in August 1853.

The governor of Tennessee had little power. Johnson could suggest laws but not veto them. Most appointments were made by the Whig legislature. But the office allowed him to share his political views. He helped establish the state's public library. He also started the first public school system. He began regular state fairs to help craftsmen and farmers.

The Whig Party was declining nationally. But it was still strong in Tennessee. Johnson ran for re-election in 1855. He won again, but by a smaller margin.

As the 1856 presidential election neared, Johnson hoped to be nominated. He was seen as a possible compromise candidate. But the nomination went to James Buchanan. Johnson campaigned for Buchanan, who won.

Johnson decided not to run for a third term as governor. He wanted to be elected to the U.S. Senate. In 1857, he was in a train accident. His right arm was seriously injured. This injury bothered him for years.

Becoming a U.S. Senator

The Tennessee legislature would elect a U.S. Senator in October 1857. Johnson campaigned widely. His party won control of the legislature. Two days after his final speech as governor, the legislature elected him to the Senate. His opponents were very upset.

Johnson was popular among small farmers and tradesmen. He called them "plebeians." He was less popular with wealthy planters and lawyers. But no one could get as many votes as he could. He always dressed well. He had the energy for long campaigns. He relied on friends and advisors for support.

Johnson took his Senate seat in December 1857. His wife and family did not come with him. Eliza visited Washington only once during his first time as senator. Johnson immediately introduced the Homestead Bill. But many senators who supported it were from the North. This made it tied to the issue of slavery. Southern senators worried that new settlers would be non-slaveholders from the North. The Supreme Court's ruling in Dred Scott v. Sandford also complicated things. This ruling said slavery could not be banned in territories.

Johnson, a slaveholding senator from the South, tried to convince his colleagues. He argued that the Homestead Bill and slavery could exist together. But Southern opposition helped defeat the bill. In 1859, it failed again. In 1860, a weaker version passed both houses. But President Buchanan vetoed it. Johnson continued to oppose government spending. He chaired a committee to control it.

He argued against funding for building in Washington, D.C. He said it was unfair for state citizens to pay for the city's streets. He also opposed spending money on troops to stop the Mormon revolt in Utah. He argued for temporary volunteers instead of a standing army.

The Secession Crisis

In October 1859, John Brown raided a federal arsenal. This increased tensions between pro-slavery and anti-slavery groups. Johnson gave a speech in the Senate in December. He criticized Northerners who wanted to outlaw slavery. He said the Declaration of Independence's "all men are created equal" did not apply to African Americans. By this time, Johnson was a wealthy man who owned 14 enslaved people.

Johnson hoped to be a compromise candidate for president in 1860. But the Democratic Party split over slavery. Northerners supported Stephen Douglas. Southerners, including Johnson, supported John C. Breckinridge. With a fourth candidate, John Bell, also running, the Republican Party elected its first president, Abraham Lincoln. Many Southerners found Lincoln's election unacceptable. They began talking about leaving the Union.

Johnson spoke in the Senate after the election. He said he would not give up on the government. He invited all patriots to stand by the Constitution and preserve the Union. He reminded Southern senators that if they stayed, Democrats would control the Senate. They could protect the South's interests. But Johnson had upset Southern leaders, including Jefferson Davis. Davis would soon be the president of the Confederate States of America.

Johnson returned home when Tennessee considered secession. The governor and legislature held a vote on leaving the Union. Johnson campaigned against it, even with threats to his life. His part of Tennessee was mostly against secession. But the state voted to join the Confederacy in June 1861. Johnson believed he would be killed if he stayed. He fled through the Cumberland Gap. His wife and family stayed in Greeneville.

Johnson was the only senator from a seceded state to remain in Congress. He was a key advisor to Lincoln in the early war months. He tried to convince Union commanders to invade East Tennessee.

Military Governor of Tennessee

Johnson's time in the Senate ended in March 1862. Lincoln appointed him military governor of Tennessee. Much of the state had been retaken by the Union. The Senate quickly confirmed Johnson's appointment. He was given the rank of brigadier general. In response, the Confederates took his land and enslaved people. They turned his home into a military hospital. Later in 1862, the Homestead Bill finally became law. This bill, along with others, helped open the Western United States for settlement.

As military governor, Johnson worked to remove rebel influence. He demanded loyalty oaths from officials. He closed newspapers that supported the Confederacy. Johnson defended Nashville from Confederate raids. His wife and family were allowed to join him.

When Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, it freed enslaved people in Confederate areas. But Tennessee was exempted at Johnson's request. Johnson eventually decided slavery had to end. He said if slavery tried to overthrow the government, the government had a right to destroy it. He helped recruit 20,000 black soldiers for the Union Army.

Vice President and President

Becoming Vice President

In 1864, Lincoln chose Johnson as his running mate for re-election. Lincoln wanted to show national unity. Johnson was a Democrat from the South who supported the Union. This sent a message about the country's ability to stay together.

Lincoln ran under the name National Union Party. This was instead of the Republican Party. At the party's convention in Baltimore in June, Lincoln was easily nominated. Johnson was nominated for vice president on the second ballot. Lincoln was happy with the choice. When Johnson heard the news, he gave a speech. He said his selection as a Southerner meant the rebel states had not truly left the Union.

Johnson actively campaigned, which was unusual then. He gave speeches in Tennessee, Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana. He also made the loyalty oath for voters in Tennessee stricter. This helped his chances there. Lincoln and Johnson won the election easily.

As Vice President-elect, Johnson wanted to finish setting up civilian government in Tennessee. But Lincoln's advisors told him he had to be sworn in with Lincoln. On March 4, 1865, Johnson was unwell. He gave a difficult speech at the Capitol. He was then sworn in as vice president. Lincoln then gave his famous Second Inaugural Address.

In the weeks after, Johnson mostly stayed out of public view. He planned to return to Tennessee. But then news came that Union General Ulysses S. Grant had captured the Confederate capital. This meant the war was ending.

Taking Office as President

On April 14, 1865, Lincoln and Johnson met. Johnson wanted Lincoln to be tough on former rebels. That night, President Lincoln was shot and killed at Ford's Theatre. This was part of a plot to kill Lincoln, Johnson, and Secretary of State Seward. Seward was badly hurt, but Johnson was not attacked.

Lincoln died the next morning. Johnson was sworn in as president between 10 and 11 AM. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase led the ceremony. Johnson's mood was described as "solemn and dignified." He held his first Cabinet meeting and asked all members to stay.

There was some talk about the plot against Johnson. On the day of the assassination, John Wilkes Booth left a card for Johnson. It said, "Don't wish to disturb you. Are you at home? J. Wilkes Booth."

Johnson led Lincoln's funeral ceremonies in Washington. He then sent Lincoln's body home to Illinois. Soon after Lincoln's death, General William T. Sherman made a deal with Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston. This deal would have allowed the Confederate government to stay in power. It also would have respected property rights, including enslaved people. Johnson and his Cabinet rejected this. They told Sherman to get a surrender without political deals. Johnson also offered a $100,000 reward for Confederate President Davis. This made Johnson seem tough on the South. He also allowed the execution of Mary Surratt for her role in Lincoln's assassination.

Reconstruction Efforts

When Johnson became president, he faced the big question: what to do with the former Confederate states? President Lincoln had allowed loyal governments in some states. His plan would let states hold elections after 10% of voters swore loyalty. But Congress thought this was too easy. Their plan needed a majority of voters to swear loyalty. Lincoln had stopped their plan.

Johnson had three main goals for Reconstruction. First, he wanted states to rejoin the Union quickly. He believed they had never truly left. Second, he wanted political power in the South to shift from wealthy planters to common people. He worried that freed African Americans might vote as their former masters told them. Third, Johnson wanted to be elected president in 1868. He hoped to build a group of Democrats and others who opposed Congress's Reconstruction plans.

Republicans in Congress had different ideas. Radical Republicans wanted voting and other civil rights for African Americans. They thought freedmen would vote Republican. This would keep Republicans in power and former rebels out. They also wanted to punish top Confederates. Moderate Republicans wanted to keep Democrats out of power. They also wanted to prevent former rebels from regaining power. They were less enthusiastic about black suffrage. Northern Democrats wanted the Southern states to rejoin without conditions. They did not support black suffrage.

Johnson's Plan for Reconstruction

Johnson started his Reconstruction policy while Congress was not meeting. Radical Republicans urged him to demand rights for freedmen. But Johnson insisted that voting was a state matter, not a federal one. His Cabinet was divided.

Johnson's first actions were two announcements on May 29. One recognized the government in Virginia. The second offered forgiveness to most former rebels. But it excluded those with property worth $20,000 or more. It also appointed a temporary governor for North Carolina and allowed elections. These announcements did not include anything about black voting rights. The President ordered other former rebel states to hold constitutional conventions.

Southern states began forming governments. Johnson's policies were popular in the North at first. He thought this meant full support for quickly bringing the South back. White Southerners supported him. But he did not realize how determined Northerners were. They wanted to make sure the war had not been fought for nothing. Northerners wanted the South to admit defeat. They wanted slavery ended. And they wanted African Americans' lives to improve. Voting rights were less important to many Northerners. Only a few Northern states allowed black men to vote on the same terms as whites.

Instead, white Southerners felt encouraged. Many Southern states passed "Black Codes". These laws forced African American workers to sign yearly contracts. They could not quit. Law enforcement could arrest them for not having a job. Then they could rent out their labor. Most Southerners elected to Congress were former Confederates. This included Alexander Stephens, the former Confederate vice president. Congress met in December 1865. Johnson's message to them was well received. But Congress refused to seat the Southern lawmakers. They created a committee to suggest new Reconstruction laws.

Northerners were angry that unrepentant Confederate leaders might rejoin the government. They saw the Black Codes as making African Americans almost enslaved again. Republicans also feared that restoring the Southern states would bring Democrats back to power. Violence and poverty in the South also fueled opposition to Johnson.

Disagreement with Republicans

Congress was hesitant to challenge the President at first. They only wanted to adjust Johnson's policies. Johnson was unhappy about the Southern states' actions. He did not like that the old elite was still in control. But he did not say so publicly. He believed Southerners had the right to act as they wished. By early 1866, he thought he needed to win a fight with the Radical Republicans. He wanted this for his political plans and for re-election.

Senator Lyman Trumbull, a Moderate Republican, wanted to work with Johnson. He helped pass a bill to extend the Freedmen's Bureau. This agency helped former slaves. He also passed the first Civil Rights Bill. This bill would grant citizenship to freedmen. Trumbull met with Johnson several times. He thought Johnson would sign the bills. But Johnson opposed both bills. He saw them as interfering with state power. He also knew these bills were unpopular with white Southerners. Johnson hoped to include them in his new political party.

Johnson vetoed the Freedmen's Bureau bill on February 18, 1866. White Southerners were happy. Republican lawmakers were confused and angry. Johnson thought this would isolate the Radicals. He believed Moderate Republicans would support him. But he did not understand that Moderates also wanted fair treatment for African Americans.

On February 22, Johnson gave an unplanned speech. He spoke for an hour. He mentioned himself over 200 times. He also named Congressmen Thaddeus Stevens and Senator Charles Sumner. He accused them of plotting against him. Republicans saw this as a declaration of war. One Democrat said Johnson's speech cost the party 200,000 votes in the 1866 elections.

Moderates urged Johnson to sign the Civil Rights Act of 1866. But Johnson vetoed it on March 27. He said it gave citizenship to freedmen when many states were not represented in Congress. He also said it favored African Americans over whites. Within three weeks, Congress overrode his veto. This was the first time a major bill was passed over a presidential veto in U.S. history. This veto convinced moderates that they could not work with Johnson. Historians see it as a major mistake.

Congress also proposed the Fourteenth Amendment. Johnson opposed it. But the president plays no part in states ratifying amendments. This amendment would put parts of the Civil Rights Act into the Constitution. It also gave citizenship to everyone born in the U.S. (except Native Americans on reservations). It punished states that did not let freedmen vote. It also created new federal civil rights. It guaranteed federal debt would be paid. It also said Confederate war debts would not be repaid. Many former Confederates were disqualified from holding office. Congress, not the president, could remove this disqualification.

Congress passed the Freedmen's Bureau Act a second time. Johnson vetoed it again. This time, his veto was overridden. By summer 1866, Johnson's way of restoring states was in trouble. His home state of Tennessee ratified the Fourteenth Amendment despite his opposition. When Tennessee did so, Congress immediately seated its lawmakers. This embarrassed Johnson.

Efforts to compromise failed. A political war began between Republicans and Johnson. Johnson tried to unite his supporters under the National Union Party. He hoped to win a full term in 1868. The battle was the election of 1866. Southern states were not allowed to vote. Johnson campaigned hard. He went on a public speaking tour called the "Swing Around the Circle". This trip was a disaster. He made controversial comparisons and argued with hecklers. Republicans won by a landslide. They increased their majority in Congress. They planned to control Reconstruction.

Radical Reconstruction

Even after the Republican victory, Johnson felt strong. The Fourteenth Amendment had not been ratified by most Southern or border states. He thought this deadlock would help him win in 1868. When Congress met in December 1866, they passed many laws over his veto. This included a voting bill for Washington, D.C. Congress also admitted Nebraska to the Union over a veto. Nebraska quickly ratified the Fourteenth Amendment.

In January 1867, Congressman Stevens proposed a law. It would divide the South into five military districts. These states would be under martial law. They would hold new constitutional conventions. African Americans could vote and become delegates. Former Confederates could not. Congress added that states would rejoin the Union after ratifying the Fourteenth Amendment. Johnson and Southerners tried to compromise. But Republicans insisted on the full amendment.

Johnson vetoed the First Reconstruction Act on March 2, 1867. Congress overrode his veto the same day. Also on March 2, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act over his veto. This law required Senate approval to fire Cabinet members. It was passed because Johnson had said he would fire Cabinet members who disagreed with him. This law was controversial. Some senators doubted if it was constitutional. They also wondered if it applied to Johnson. His main Cabinet officers were appointed by Lincoln.

Impeachment Trial

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton was a skilled but difficult person. Johnson admired him but was also frustrated by him. Stanton and General Ulysses S. Grant worked against the president's Southern policies. Johnson thought about firing Stanton. But he respected Stanton's service during the war. Stanton refused to resign. He feared Johnson would appoint someone else.

Congress met briefly in March 1867. The House Committee on the Judiciary was tasked with investigating Johnson for impeachment. They looked at his bank accounts. They called Cabinet members to testify. When former Confederate president Davis was released on bail, they checked if Johnson had stopped his trial. They found Johnson wanted Davis tried. A majority of the committee voted against impeachment.

Later, Johnson and Stanton argued. This was about whether military officers in the South could overrule civilian leaders. Johnson's Attorney General said they could not. Johnson wanted Stanton to take a side. Stanton avoided the issue. When Congress met again in July, they passed a Reconstruction Act against Johnson's position. They overrode his veto and went home. This law clarified the generals' powers. It also took away the President's control over the Army in the South.

With Congress away, Johnson decided to fire Stanton. He also wanted to remove General Philip Sheridan. Sheridan had angered Johnson by following Congress's plan. Johnson was at first stopped by Grant. But on August 5, Johnson demanded Stanton's resignation. Stanton refused. Johnson then suspended him. He appointed Grant as temporary replacement.

Grant followed Johnson's orders to move Sheridan. Johnson also issued a pardon for most Confederates. But it excluded those who held office under the Confederacy. It also excluded those who broke their oaths after serving in federal office before the war. Republicans were angry. But the 1867 elections generally favored Democrats. Voters in Ohio, Connecticut, and Minnesota rejected proposals to give African Americans the right to vote.

These results temporarily stopped Republican calls to impeach Johnson. Johnson was happy about the elections. But when Congress met in November, the Judiciary Committee changed its mind. They passed a resolution to impeach Johnson. After much debate, the House of Representatives voted against impeachment on December 7, 1867. The vote was 57 in favor to 108 opposed.

Johnson told Congress about Stanton's suspension and Grant's temporary appointment. In January 1868, the Senate disagreed. They reinstated Stanton. They said Johnson had violated the Tenure of Office Act. Grant stepped aside. This caused a complete break between Johnson and Grant. Johnson then fired Stanton and appointed Lorenzo Thomas. Stanton refused to leave his office. On February 24, 1868, the House impeached the President. They said he intentionally violated the Tenure of Office Act. The vote was 128 to 47. The House then adopted eleven articles of impeachment. Most said he violated the Tenure of Office Act. They also said he questioned Congress's power.

The impeachment trial began in the Senate on March 5, 1868. It lasted almost three months. Congressmen George S. Boutwell, Benjamin Butler, and Thaddeus Stevens were the prosecutors. William M. Evarts, Benjamin R. Curtis, and former Attorney General Henry Stanbery were Johnson's lawyers. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase was the judge.

The defense argued that the Tenure of Office Act only applied to people appointed by the current president. Since Lincoln appointed Stanton, they said Johnson did not violate the law. They also argued that the President had the right to test if a law was constitutional. Johnson's lawyers told him not to appear at the trial. They also told him not to comment publicly. He mostly followed this advice.

Johnson worked to get acquitted. He promised Senator James W. Grimes he would not interfere with Congress's Reconstruction plans. Grimes told other Moderates, many of whom voted for acquittal, that he believed Johnson. Johnson also promised to appoint John Schofield as War Secretary. Senator Edmund G. Ross received promises that new state constitutions would be sent to Congress quickly. This would give him and other senators a reason to vote for acquittal.

Some senators did not want to remove Johnson. His successor would have been Senator Benjamin Wade. Wade was a Radical who supported women's suffrage. This made him unpopular in much of the country. Also, a President Wade was seen as a problem for Grant's presidential hopes.

Johnson was confident of the outcome. On May 16, the Senate voted on the 11th article of impeachment. This article accused Johnson of firing Stanton illegally. Thirty-five senators voted "guilty" and 19 "not guilty." This was one vote short of the two-thirds needed to convict. Ten Republicans voted to acquit the President. The Senate then took a break for the 1868 Republican National Convention. Grant was nominated for president. The Senate returned on May 26. They voted on two more articles, with the same results. Johnson's opponents gave up. Stanton left his office. The Senate then confirmed Schofield.

There were claims that bribery affected the trial's outcome. Representative Butler investigated this. He focused on a group that supposedly raised money to bribe senators. Butler even imprisoned a lawyer named Charles Woolley. But he failed to prove bribery.

Foreign Policy

Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward agreed to keep the same foreign policy. Seward would continue to manage foreign affairs. At the time, France had sent troops to Mexico. Seward preferred quiet talks. He warned France that their presence in Mexico was not acceptable. Johnson wanted a tougher approach. But Seward convinced him to follow his lead. In April 1866, France said its troops would leave Mexico by November 1867.

Seward wanted to gain more land for the United States. Russia saw its North American colony (now Alaska) as a financial burden. They feared losing it to Britain. Talks between Russia and the U.S. about selling Alaska had stopped during the Civil War. But they started again after the war. Russia told its minister in Washington to negotiate a sale. He got Seward to raise his offer to $7 million. Then he got another $200,000 added. This totaled $7.2 million. On March 30, 1867, they signed the treaty. Johnson and Seward took the document to the Capitol. But they were told there was no time to deal with it before Congress ended its session. The President called the Senate to meet on April 1. The Senate approved the treaty, 37-2.

Encouraged by this success, Seward looked for other acquisitions. He only succeeded in claiming uninhabited Wake Island in the Pacific. He almost bought the Danish West Indies. Denmark agreed to sell them. The local people approved. But the Senate never voted on the treaty.

Another treaty that failed was the Johnson-Clarendon convention. This was to settle the Alabama Claims. These were for damages to American ships from British-built Confederate ships. The Senate ignored this treaty. It was rejected after Johnson left office. The Grant administration later got much better terms from Britain.

Cabinet and Judges

| The Andrew Johnson Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Andrew Johnson | 1865–1869 |

| Vice President | none | 1865–1869 |

| Secretary of State | William H. Seward | 1865–1869 |

| Secretary of Treasury | Hugh McCulloch | 1865–1869 |

| Secretary of War | Edwin Stanton | 1865–1868 |

| John Schofield | 1868–1869 | |

| Attorney General | James Speed | 1865–1866 |

| Henry Stanbery | 1866–1868 | |

| William M. Evarts | 1868–1869 | |

| Postmaster General | William Dennison Jr. | 1865–1866 |

| Alexander Randall | 1866–1869 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Gideon Welles | 1865–1869 |

| Secretary of the Interior | John Palmer Usher | 1865 |

| James Harlan | 1865–1866 | |

| Orville Hickman Browning | 1866–1869 | |

Johnson appointed nine federal judges during his presidency. All of them were for United States district courts. He did not appoint any judges to the Supreme Court. In 1866, Congress removed a Supreme Court seat. This was to prevent Johnson from making an appointment.

Reforms and End of Term

In June 1866, Johnson signed the Southern Homestead Act. He believed it would help poor white people. About 28,000 land claims were successful. But few former slaves benefited. Much of the best land was reserved for veterans or railroads. In June 1868, Johnson signed a law for an eight-hour workday. This was for federal government workers. However, wages were cut by 20%.

Johnson sought the Democratic nomination for president in 1868. He was very popular among Southern whites. He increased this popularity by pardoning most Confederates before the convention. On the first vote, Johnson was second. But his support dropped. Former New York governor Horatio Seymour was nominated. Johnson received only four votes.

His conflict with Congress continued. Johnson proposed amendments to limit the president to one six-year term. He also wanted direct election of the president and Senate. He wanted term limits for judges. Congress did not act on these. When Johnson was slow to report the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, Congress passed a bill. It required him to report ratifications within ten days. He still delayed. But in July 1868, he had to report the ratifications. This made the amendment part of the Constitution.

Seymour's campaign wanted Johnson's support. But Johnson stayed quiet for a long time. He did not mention Seymour until October. He never officially endorsed him. Johnson regretted Grant's victory. In his annual message to Congress in December, Johnson urged repealing the Tenure of Office Act. He said if Southern lawmakers had been admitted in 1865, everything would have been fine. He celebrated his 60th birthday with a party for children. But President-elect Grant's children did not attend.

On Christmas Day 1868, Johnson issued a final pardon. This covered everyone, including Davis. In his last months, he also pardoned people for crimes. This included Samuel Mudd, who was convicted in the Lincoln assassination.

On March 3, Johnson hosted a large public reception at the White House. Grant did not want to ride in the same carriage as Johnson for the inauguration. Johnson refused to go to the inauguration at all. He spent the morning of March 4 finishing business. Then he left the White House for a friend's home.

After the Presidency

After leaving the presidency, Johnson stayed in Washington for a few weeks. Then he returned to Greeneville for the first time in eight years. People celebrated his return, especially in Tennessee. He had bought a large farm near Greeneville.

Some thought Johnson would run for governor or senator again. Johnson found Greeneville boring. He decided to run for the Senate to get back at his political enemies. Tennessee had become Republican. But court rulings and violence from the Ku Klux Klan suppressed African American votes. This led to a Democratic victory in 1869. Johnson was seen as likely to win the Senate election. But Republicans elected Henry Cooper instead. In 1872, Johnson ran for a congressional seat as an independent. He lost, finishing third.

In 1873, Johnson got cholera but recovered. He also lost about $73,000 when a bank failed. But he eventually got most of the money back.

Return to the Senate

Johnson looked toward the next Senate election in early 1875. He gained support from the farmers' Grange movement. He spoke across the state. Few African Americans could vote in Tennessee by this time. This pattern would spread to other Southern states. In the Tennessee elections in August, Democrats won many seats. Johnson went to Nashville for the legislative session.

When the Senate vote began on January 20, 1875, Johnson led. But he did not have enough votes. His opponents tried to agree on one candidate to defeat him. But they failed. Johnson was elected on January 26 on the 54th vote. He won by just one vote. Nashville celebrated. Johnson said, "Thank God for the vindication."

Johnson's comeback gained national attention. He was sworn into the Senate on March 5, 1875. He was greeted with flowers. Many Republicans ignored him. But some shook his hand. Johnson is still the only former president to serve in the Senate. He spoke only once in that short session. On March 22, he criticized President Grant. He spoke against Grant's use of federal troops in Louisiana. He asked, "How far off is military despotism?" He ended his speech saying, "may God bless this people and God save the Constitution."

Death

Johnson returned home after the special session. In late July 1875, he decided to travel to Ohio to give speeches. He believed some opponents were slandering him there. He started his trip on July 28. He stopped at his daughter Mary's farm near Elizabethton. His daughter Martha was also there. That evening, he had a stroke. He refused medical help until the next day. He seemed to get better. But he had another stroke on July 30. He died early the next morning at age 66.

President Grant announced Johnson's death. Northern newspapers focused on Johnson's loyalty during the war. Southern papers praised his actions as president. Johnson's funeral was on August 3 in Greeneville. He was buried wrapped in an American flag. A copy of the U.S. Constitution was placed under his head, as he wished. The burial ground became the Andrew Johnson National Cemetery in 1906. It is part of the Andrew Johnson National Historic Site, along with his home and tailor's shop.

Andrew Johnson's Place in History

Historians often focus on Johnson's role in Reconstruction. For the rest of the 1800s, there were few historical reviews of Johnson. Memoirs from Northerners who knew him described him as stubborn. They said he tried to favor the South but was stopped by Congress. Historians at the time often wrote to justify their own views.

In the early 1900s, the first major historical reviews of Johnson appeared. Some historians believed Johnson had flaws. They thought he was politically clumsy. But they concluded he tried to carry out Lincoln's plans for the South. Some writers said Reconstruction was a harsh program. They claimed it hurt Southerners and benefited Northerners who took advantage of the situation.

Later, historians started to look at Johnson more favorably. They used his personal papers and diaries. These works presented him much better than those who tried to remove him from office. Historians still saw Johnson as having deep flaws. But they thought his Reconstruction policies were mostly correct.

In the 1950s, historians began to focus on the African American experience in Reconstruction. They rejected ideas of black inferiority. They saw the growing civil rights movement as a second Reconstruction. These authors supported the Radical Republicans. They liked their desire to help African Americans. They saw Johnson as uncaring towards freed people. Many books from this time showed Johnson as someone who stopped efforts to improve the lives of freedmen. Reconstruction was increasingly seen as a good effort to include former slaves in society.

Today, Johnson is often listed among the worst presidents in U.S. history. Historians say this is because of his impeachment. They also point to his poor handling of Reconstruction. His difficult personality and strong sense of self-importance are also mentioned. Some historians note that Johnson, along with other presidents of his time, faced huge problems. They say it would have taken many leaders like Lincoln to handle them well.

Images for kids

-

Johnson's birthplace and childhood home, located at the Mordecai Historic Park in Raleigh, North Carolina

-

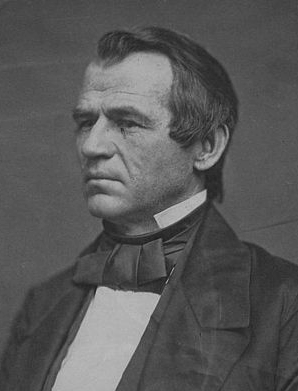

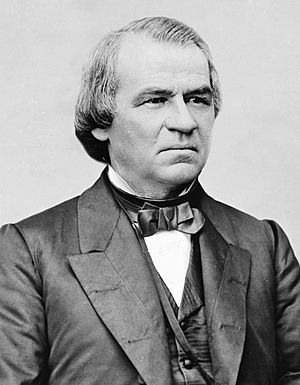

Poster for the Lincoln and Johnson ticket by Currier and Ives

-

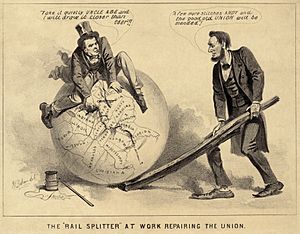

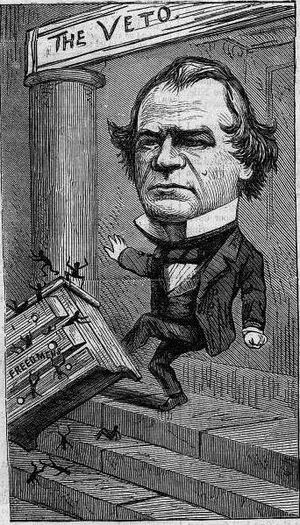

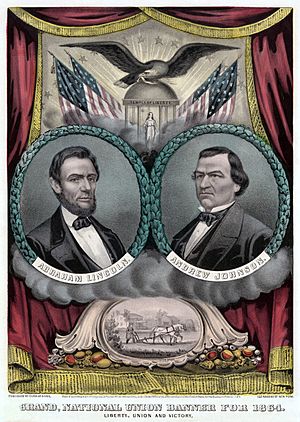

Thomas Nast cartoon of Johnson disposing of the Freedmen's Bureau as African Americans go flying

-

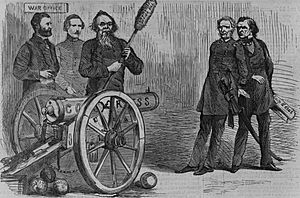

"The Situation", a Harper's Weekly editorial cartoon, shows Secretary of War Stanton aiming a cannon labeled "Congress" to defeat Johnson. The rammer is "Tenure of Office Bill" and cannonballs on the floor are "Justice".

-

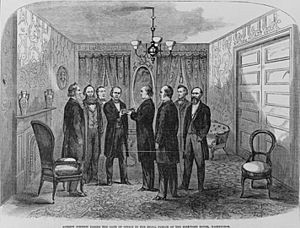

Illustration of Johnson's impeachment trial in the United States Senate, by Theodore R. Davis, published in Harper's Weekly

See Also

In Spanish: Andrew Johnson para niños

In Spanish: Andrew Johnson para niños