Edwin Stanton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edwin Stanton

|

|

|---|---|

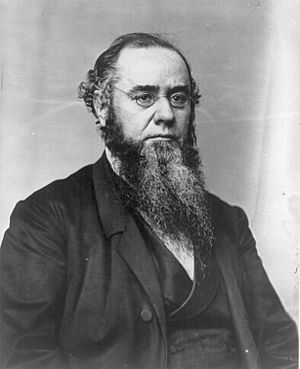

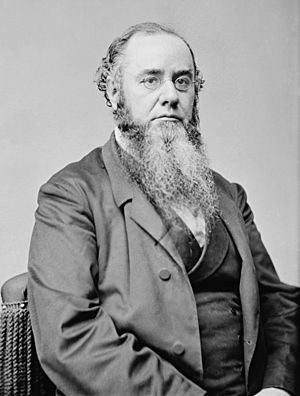

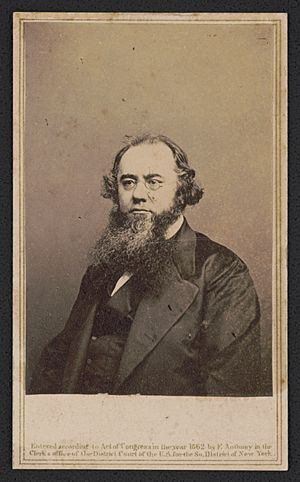

Photograph by Mathew Brady, c. 1866-1869

|

|

| 27th United States Secretary of War | |

| In office January 20, 1862 – May 28, 1868 |

|

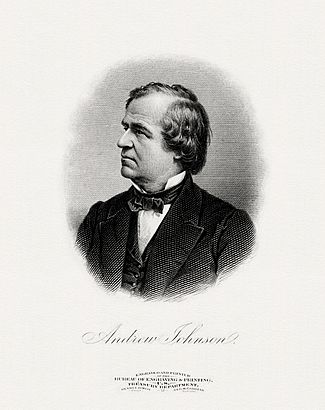

| President | Abraham Lincoln Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | Simon Cameron |

| Succeeded by | John Schofield |

| 25th United States Attorney General | |

| In office December 20, 1860 – March 4, 1861 |

|

| President | James Buchanan |

| Preceded by | Jeremiah Black |

| Succeeded by | Edward Bates |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Edwin McMasters Stanton

December 19, 1814 Steubenville, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | December 24, 1869 (aged 55) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Oak Hill Cemetery Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (before 1862) Republican (1862–1869) |

| Spouses |

Mary Lamson

(m. 1836–1844)Ellen Hutchison

(m. 1856) |

| Parents |

|

| Education | Kenyon College |

| Signature | |

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814 – December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician. He served as the U.S. Secretary of War for most of the American Civil War under President Abraham Lincoln. Stanton helped organize the huge military efforts of the North, which led the Union to victory. However, some generals thought he was too careful and tried to control too many small details. He also led the search for Lincoln's killer, John Wilkes Booth.

After Lincoln was killed, Stanton stayed on as Secretary of War for the new president, Andrew Johnson. This was during the first years of the Reconstruction Era, when the country was rebuilding. Stanton disagreed with Johnson's kind approach toward the former Confederate States. Johnson tried to fire Stanton, which eventually led to Johnson being impeached (accused of wrongdoing) by a group called the Radical Republicans in the House of Representatives. Stanton later went back to working as a lawyer. In 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant nominated him to be a Supreme Court Justice. But Stanton died just four days after the Senate approved his nomination.

Contents

Edwin Stanton's Early Life

Family Background

Before the American Revolution, Edwin Stanton's family, the Stantons and Macys, were Quakers and lived in Massachusetts. They later moved to North Carolina. In 1774, his grandfather, Benjamin Stanton, married Abigail Macy. After Benjamin died in 1800, Abigail moved to the Northwest Territory with her family. This area soon became the state of Ohio.

Abigail Macy was important in developing the new state. She bought land in Mount Pleasant, Ohio, and settled there. One of her sons, David, became a doctor in Steubenville, Ohio. He married Lucy Norman, whose father was a planter from Virginia. David's marriage to Lucy, who was a Methodist and not a Quaker, caused him to leave the Quaker community.

Childhood and School

Edwin McMasters Stanton was born on December 19, 1814, in Steubenville, Ohio. He was the first of David and Lucy Stanton's four children. Edwin first went to a private school and a seminary (a school for religious studies) near his home. When he was ten, he moved to a school taught by a Presbyterian minister.

At age ten, Edwin also had his first asthma attack. This illness bothered him his whole life, sometimes causing severe fits. Because of his asthma, he couldn't do many physical activities. Instead, he loved reading books and poetry. Edwin regularly attended Methodist church services and Sunday school. By age thirteen, he became a full member of the Methodist church.

David Stanton's medical practice provided a good life for his family. But when David suddenly died in December 1827, Edwin and his family were left without money. Edwin's mother opened a store in their home. She sold her husband's medical supplies, along with books, stationery, and groceries. Young Edwin had to leave school and work at a local bookstore.

In 1831, Stanton started college at Kenyon College, which was connected to the Episcopal Church. He joined the Philomathesian Literary Society, where he participated in debates. Stanton had to leave Kenyon at the end of his third semester because he ran out of money. While at Kenyon, he supported President Andrew Jackson's actions during the 1832 Nullification Crisis. This led him to join the Democratic Party. He also became an Episcopalian and strongly disliked slavery. After Kenyon, Stanton worked in a bookstore in Columbus, Ohio. He hoped to save enough money to finish college, but his small salary made that impossible. He soon returned to Steubenville to study law.

Early Career and First Marriage

Stanton studied law with Daniel Collier to prepare for becoming a lawyer. He was allowed to practice law in 1835. He then started working at a well-known law firm in Cadiz, Ohio, with Chauncey Dewey. Stanton often handled the firm's trial cases.

When he was 18, Stanton met Mary Ann Lamson in Columbus. They soon became engaged. After buying a home in Cadiz, Stanton went to Columbus to marry Mary. They wanted to marry at Trinity Episcopal Church, but Stanton's illness prevented it. Instead, they married at the church's rector's home on December 31, 1836. Afterward, Stanton brought his mother and sisters from Virginia to live with him and his wife in Cadiz.

After his marriage, Stanton became partners with lawyer and federal judge Benjamin Tappan. Stanton's sister also married Tappan's son. In Cadiz, Stanton became an important part of the community. He worked with the town's anti-slavery group and wrote for a local newspaper, the Sentinel. In 1837, he was elected the prosecutor for Harrison County, Ohio, as a Democrat. Stanton's growing wealth allowed him to buy a large piece of land in Washington County, Ohio, and several properties in Cadiz.

A Rising Attorney (1839–1860)

Back in Steubenville

Stanton's connection with Benjamin Tappan grew when Tappan was elected a United States Senator from Ohio in 1838. Tappan asked Stanton to manage his law practice in Steubenville. After his time as county prosecutor ended, Stanton moved back to Steubenville. His involvement in politics also increased. He was a delegate at the Democrats' 1840 national convention in Baltimore. He also played a big role in Martin Van Buren's campaign for the 1840 United States presidential election, which Van Buren lost.

In Steubenville, the Stantons had two children: a daughter, Lucy Lamson, born in March 1840, and a son, Edwin Lamson, born in August 1842. Lucy became ill within months of her birth. Stanton stopped working and spent the summer by her side. She died in late 1841. Edwin, however, was healthy and active. His birth brought joy back to the Stanton home after Lucy's death. But sadness returned in 1844 when Mary Stanton became sick and died in March 1844. Stanton was deeply saddened.

By summer, Stanton focused on his law cases again. One important case was defending Caleb J. McNulty. McNulty, a Democrat, was fired from his job as a clerk of the United States House of Representatives and accused of embezzlement (misusing money) when thousands of dollars went missing. Democrats wanted McNulty punished to protect their party's reputation. Stanton, asked by Tappan, became McNulty's lawyer. Stanton successfully argued to dismiss the charges, surprising the courtroom. Newspapers across the country covered the case, making Stanton's name well-known.

After the McNulty case, Stanton and Tappan ended their professional partnership. Stanton then partnered with one of his former students, George Wythe McCook. When the Mexican–American War began, many men joined the United States Army, including McCook. Stanton wanted to join too, but his doctor worried about his asthma. So, he focused on law. Stanton's law practice grew beyond Ohio to Virginia and Pennsylvania. He decided Steubenville was no longer a good base and moved his main office to Pittsburgh. He was allowed to practice law there by late 1847.

Lawyer in Pittsburgh

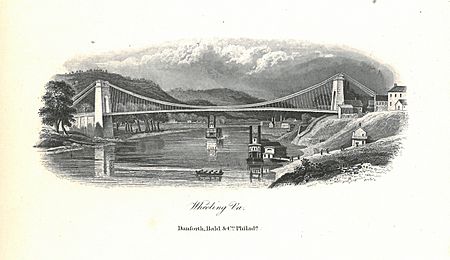

In Pittsburgh, Stanton partnered with a well-known retired judge, Charles Shaler. He also continued working with McCook, who stayed in Steubenville after returning from the Mexican–American War. Stanton handled several important cases. One was State of Pennsylvania v. Wheeling and Belmont Bridge Company and others in the United States Supreme Court. This case was about the Wheeling Suspension Bridge, which was the largest suspension bridge in the world at the time. It was an important connection for the National Road.

The bridge's center was about 90 feet high, but it caused problems for ships with tall smokestacks. If ships couldn't pass, a lot of trade would go to Wheeling, West Virginia. On August 16, 1849, Stanton asked the Supreme Court to stop Wheeling and Belmont from using the bridge because it blocked traffic into Pennsylvania and hurt trade. The Supreme Court eventually ruled that the bridge was an illegal obstruction and ordered its height to be increased to 111 feet. However, Wheeling and Belmont asked Congress to act. To Stanton's dismay, Congress passed a law on August 31, allowing the Wheeling bridge to stay as it was. This effectively overturned the Supreme Court's decision. Stanton was upset that Congress had weakened the court's power to settle disputes between states.

McCormick v. Manny

Stanton's work in the Wheeling Bridge case led him to other important cases, like the McCormick Reaper patent case. This involved inventor Cyrus McCormick and his machine for harvesting crops. McCormick's invention was very popular, especially in the growing wheat fields of the Western United States. This led to strong competition, especially from another inventor, John Henry Manny. In 1854, McCormick and his lawyers sued Manny, saying he had copied McCormick's patents.

The case was first supposed to be heard in Chicago. Manny's lawyers, George Harding and Peter H. Watson, wanted a local lawyer to join their team. They considered Abraham Lincoln. Watson met Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois, and at first wasn't impressed. But after talking, he thought Lincoln might be a good choice. However, the trial was moved to Cincinnati, so Lincoln wasn't needed as a local lawyer. Harding and Watson chose Edwin Stanton instead. Lincoln wasn't told he'd been replaced, but he still showed up in Cincinnati with his arguments ready. Stanton immediately disliked Lincoln and made it clear he wanted Lincoln to leave the case. Lincoln didn't actively participate but stayed to watch.

Stanton's job in Manny's legal team was to research. He admitted that George Harding, a patent lawyer, was better at the scientific parts of the case. But Stanton worked to summarize the relevant laws and past cases. To win for Manny, Stanton and his team had to show the court that McCormick didn't have exclusive rights to a part of his reaper called a "divider." This part separated the grain and was essential for the machine to work.

Watson decided to use a trick. He hired a model maker named William P. Wood to find an older version of McCormick's reaper and change it for court. Wood found a reaper from 1844, a year before McCormick's patent. He had a blacksmith straighten the curved divider, knowing that Manny's curved divider wouldn't conflict with a straight one. Wood then added rust to make it look old and sent it to Cincinnati. Stanton was happy when he saw the changed reaper, knowing they would win. The arguments began in September 1855. In March 1856, the judges ruled in favor of John Manny. McCormick appealed to the Supreme Court, and the case became a political issue. Stanton later appointed Wood to manage military prisons during the Civil War.

Second Marriage and Move to Washington

In February 1856, Stanton became engaged to Ellen Hutchinson, who was sixteen years younger than him. Her family was important in the city; her father, Lewis Hutchinson, was a rich merchant. They married on June 25, 1856, at her father's home. Stanton then moved to Washington, D.C., where he expected to do important work with the Supreme Court.

In Pennsylvania, Stanton had become good friends with Jeremiah S. Black, the chief judge of the state's supreme court. This friendship helped Stanton when, in March 1857, the new President, James Buchanan, made Black his Attorney General. Black soon faced a problem with land claims in California. After the Mexican–American War, the U.S. agreed to recognize land grants made by Mexican authorities. The California Land Claims Act of 1851 set up a board to review these claims.

One claim was made by Joseph Yves Limantour, a French merchant, who said he owned large parts of California, including a big section of San Francisco. When the land commissioners approved his claims, the U.S. government appealed. Meanwhile, Black heard from a person named Auguste Jouan, who said Limantour's claims were fake. Jouan claimed he had forged the date on one of the approved grants for Limantour. Black needed someone loyal to the Democratic Party and President Buchanan to represent the government in California. He chose Stanton.

Ellen Stanton didn't like the idea. Edwin would be thousands of miles away for months, leaving her lonely in Washington. Also, on May 9, 1857, Ellen had a daughter they named Eleanor Adams. After the baby's birth, Ellen became sick, which worried Edwin and delayed his decision to go to California. In October 1857, Stanton finally agreed to represent the Buchanan administration in California. He agreed to be paid $25,000.

Stanton left New York City on February 19, 1858, on the ship Star of the West. His son Eddie, President Buchanan's nephew James Buchanan, Jr., and Lieutenant H. N. Harrison (assigned to Stanton by the Navy) traveled with him. After a rough journey, they docked in Kingston, Jamaica, where slavery was not allowed. Stanton enjoyed the climate there and was surprised to see Black and white people sitting together in church. They then landed in Panama and took a much larger ship, the Sonora. On March 19, they finally arrived in San Francisco and stayed at the International Hotel.

Stanton quickly started his work. To help his case, Stanton and his team organized messy records from California's time under Mexico. He found the "Jemino Index," which had information on land grants up to 1844. With help from Congress, Stanton found records from all over the state related to Mexican grants. Stanton and his team worked for months sorting the land documents. Meanwhile, Stanton's arrival caused gossip and anger among locals, especially those whose land claims might be lost if Stanton won. Also, President Buchanan and Senator Douglas were fighting for control of California, and Stanton was caught in the middle, leading to false accusations against him by Douglas's supporters. This upset Stanton, but it didn't stop his work.

Limantour had built a strong-looking case with lots of evidence, like witness statements, grants signed by Manuel Micheltorena (the Mexican governor of California), and paper with a special Mexican government stamp. However, Auguste Jouan's information was key to Stanton's case. Jouan said Limantour had received many blank documents signed by Governor Micheltorena, which Limantour could fill in as he wished. Jouan also said he had made a hole in one paper to erase something, and that hole was still there. Stanton also found letters that clearly showed the fraud, and fake stamps used by customs officials. The fake stamp had been used eleven times, all on Limantour's documents. When Stanton checked with the Minister of the Exterior in Mexico City, they couldn't find records to support Limantour's grants. In late 1858, Limantour's claims were denied, and he was arrested for lying under oath. He paid $35,000 bail and left the country.

As 1858 ended, Stanton prepared to go home, but Eddie became sick. Whenever Stanton planned to leave California, his son's condition worsened. Edwin wrote to Ellen as often as he could, as her worry and loneliness grew in Washington. She criticized him for leaving her alone with young "Ellie." On January 3, 1859, Stanton and his group left San Francisco. He was home in early February. In Washington, Stanton advised President Buchanan on patronage (giving jobs to supporters) and helped Attorney General Black a lot. Stanton's work in Washington seemed less exciting than his time in California, until he found himself defending a man who was the talk of the country.

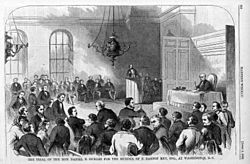

The Daniel Sickles Trial

Daniel Sickles was a member of the United States House of Representatives from New York. He was married to Teresa Bagioli Sickles. His wife had started a secret relationship with Philip Barton Key II, the U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia and son of Francis Scott Key, who wrote The Star-Spangled Banner. On February 27, 1859, Sickles confronted Key in Lafayette Square, Washington, D.C., and shot him. Sickles then went to Attorney General Black's home and admitted what he had done. A few days later, he was charged with murder. The Sickles case got national media attention because it was scandalous and happened near the White House. The press even suggested a secret relationship between Sickles' wife and President Buchanan. Famous criminal lawyer James T. Brady and his partner, John Graham, defended Sickles and asked Stanton to join their team.

The trial began on April 4. The prosecution wanted to argue that Sickles had also been unfaithful and didn't care much about his wife. When the judge didn't allow this, the prosecution focused on how terrible the shooting was, rather than Sickles' reasons. Sickles' defense argued that he had suffered a temporary moment of insanity. This was the first time such a defense was used in American law. The courtroom events were very dramatic. When Stanton gave his final arguments, saying that marriage is sacred and a man has the right to defend his marriage, the courtroom cheered. A law student called Stanton's argument "a typical piece of Victorian rhetoric, an ingenious thesaurus of aphorisms on the sanctity of the family." The jury thought for just over an hour before finding Sickles not guilty. The judge ordered Sickles to be released. Outside the courthouse, Sickles, Stanton, and their team were met by a cheering crowd celebrating the victory.

Early Political Work (1860–1862)

During the 1860 United States presidential election, Stanton supported Vice President John C. Breckinridge. He believed that only Breckinridge's victory would keep the country together. However, he privately predicted that Lincoln would win.

In Buchanan's Cabinet

In late 1860, President Buchanan was preparing his yearly State of the Union address. He asked Attorney General Black for advice on whether states could legally leave the Union. Black then asked Stanton for his opinion. Stanton approved Black's strong response to Buchanan, which said that leaving the Union was illegal. Buchanan gave his address to Congress on December 3.

Meanwhile, Buchanan's cabinet members were growing unhappy with how he handled the idea of states leaving the Union. Several thought he was too weak. On December 5, his Secretary of the Treasury, Howell Cobb, resigned. On December 9, Secretary of State Lewis Cass resigned because he was upset that Buchanan didn't defend the government's interests in the South. Black was nominated to replace Cass on December 12. About a week later, Stanton, who was in Cincinnati, was told to come to Washington right away. The Senate had approved him as Buchanan's new Attorney General. He was sworn in on December 20.

Stanton found a cabinet that was very divided over states leaving the Union. Buchanan didn't want to upset the South further and sympathized with their reasons. On December 9, Buchanan had agreed with congressmen from South Carolina that military bases in the state would not be strengthened unless they were attacked. However, on the day Stanton started his job, Maj. Robert Anderson moved his unit to Fort Sumter, South Carolina. Southerners saw this as Buchanan breaking his promise. South Carolina soon issued an ordinance of secession, declaring itself independent. Southerners demanded that federal forces leave Charleston Harbor completely, threatening violence if they didn't.

The next day, Buchanan showed his cabinet a draft of his response to South Carolina. Secretaries Thompson and Philip Francis Thomas thought the President's response was too aggressive. Stanton, Black, and Postmaster General Joseph Holt thought it was too soft. Only Isaac Toucey, Secretary of the Navy, supported the response.

Stanton was worried by Buchanan's uncertainty about the South Carolina crisis. He wanted to make the President stronger against giving in to the South's demands. On December 30, Black came to Stanton's home, and they agreed to write down their objections to Buchanan ordering a withdrawal from Fort Sumter. If he did, the two men, along with Postmaster General Holt, agreed they would resign. This would be a huge blow to the administration. Buchanan agreed with them. The South Carolina delegates received Buchanan's response on New Year's Eve 1860: the President would not withdraw forces from Charleston Harbor.

By February 1, six Southern states had followed South Carolina and declared themselves no longer part of the United States. On February 18, Jefferson Davis was sworn in as the President of the Confederate States. Meanwhile, Washington was full of rumors about plots and conspiracies. Stanton thought there would be chaos on February 13, when electoral votes were counted, but nothing happened. Again, Stanton thought there would be violence when Lincoln was sworn in on March 4, but this also didn't happen. Lincoln's inauguration gave Stanton a small hope that his efforts to defend Fort Sumter would not be wasted, and that Southern aggression would be met with force from the North. In his speech, Lincoln didn't say he would outlaw slavery everywhere, but he did say he wouldn't support states leaving the Union, and that any attempt to do so was illegal. Stanton felt cautious hope from Lincoln's words. The new President announced his cabinet choices on March 5, and by the end of that day, Stanton was no longer the attorney general. He stayed in his office for a while to help his replacement, Edward Bates, settle in.

Cameron's Advisor

On July 21, the North and South had their first major battle at Manassas Junction in Virginia, known as the First Battle of Bull Run. Northerners thought this battle would end the war and defeat the Confederacy. However, the bloody fight ended with the Union Army retreating to Washington. Lincoln wanted more soldiers afterward, as many in the North realized the war would be harder than they expected. But when over 250,000 men signed up, the federal government didn't have enough supplies for them. The War Department had states buy supplies, promising to pay them back. This led to states selling the government often damaged or worthless items at very high prices. Still, the government bought them.

Soon, Simon Cameron, Lincoln's Secretary of War, was accused of managing his department poorly. Some wanted him to resign. Cameron asked Stanton to advise him on legal matters concerning the War Department's purchases. Calls for Cameron to resign grew louder when he supported a strong speech in November 1861 by Col. John Cochrane. Cochrane said, "we should take the slave by the hand, placing a musket in it, and bid him in God's name strike for the liberty of the human race." Cameron agreed that enslaved people should be armed, but Lincoln's cabinet disagreed. Caleb B. Smith, the Secretary of the Interior, criticized Cameron for supporting Cochrane.

Cameron included a call to arm enslaved people in his report to Congress, which would be sent with Lincoln's message. Cameron gave the report to Stanton, who added a part that went even further, saying that those who rebel against the government lose their right to any property, including enslaved people. He wrote that it was "clearly the right of the Government to arm slaves when it may become necessary as it is to use gunpowder or guns taken from the enemy." Cameron gave the report to Lincoln and sent copies to Congress and the press. Lincoln wanted the parts about arming enslaved people removed. He ordered the transmission of Cameron's report to be stopped and replaced with a changed version. Congress received the version without the call to arm enslaved people, while the press received the version with it. When newspapers published the full document, Republicans criticized Lincoln, thinking he was weak on slavery and disliked that he wanted the call to arm enslaved people removed.

The President decided to fire Cameron when abolitionists in the North became upset about the controversy. Cameron would not resign until he was sure of his replacement and could leave without harming his reputation. When a job as Minister to Russia became open, Cameron and Lincoln agreed he would take it after resigning. For a replacement, Lincoln thought Joseph Holt was best, but his Secretary of State, William H. Seward, wanted Stanton to replace Cameron. Salmon Chase, Stanton's friend and Lincoln's Treasury Secretary, agreed. Stanton had been planning a business partnership in New York, but he stopped those plans when he heard about his possible nomination. Lincoln nominated Stanton for Secretary of War on January 13. He was approved two days later.

Lincoln's Secretary of War (1862–1865)

First Days in Office

Under Cameron, the War Department was often called "the lunatic asylum" because it was so disorganized. Soldiers and government officials barely respected it, and its power was often ignored. The army's generals held most of the military power, with the President and War Department only stepping in for special cases. The department also had bad relations with Congress, especially Representative John Fox Potter, who led a committee looking for Confederate supporters in the government. Potter had asked Cameron to remove about fifty people he suspected, but Cameron ignored him.

Stanton was sworn in on January 20. Right away, he worked to fix the bad relationship between Congress and the War Department. On his first day, Stanton met with Potter and fired four people Potter considered suspicious. This was fewer than the fifty Potter wanted gone, but he was still pleased. Stanton also met with Senator Benjamin Wade and his Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. This committee was a helpful ally because it could subpoena (demand) information Stanton couldn't get, and it could help Stanton remove War Department staff. Wade and his committee were happy to find an ally in the executive branch and met with Stanton often.

Stanton made many organizational changes in the department. He appointed John Tucker, an executive from the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, and Peter H. Watson, his partner from the reaper case, as his assistant secretaries. He also increased the department's staff by over sixty employees. Furthermore, Stanton asked the Senate to stop appointing military officials until he could review the more than 1,400 people up for promotion. Before Stanton, military promotions were often given to people favorable to the administration, regardless of their skills. This stopped under Stanton.

On January 29, Stanton ordered that all contracts for military materials and supplies with foreign manufacturers be canceled and replaced with contracts within the United States. No new contracts were to be made with foreign companies. This order worried Lincoln's cabinet. The United Kingdom and France were looking for reasons to recognize and support the Confederates, and Stanton's order might give them one. Secretary of State Seward thought the order would "complicate the foreign situation." But Stanton insisted, and his January 29 order remained.

Meanwhile, Stanton worked to create an effective transportation and communication network across the North. He focused on the railroad system and telegraph lines. Stanton worked with Senator Wade to pass a bill that would allow the President and his administration to take control of railroad and telegraph lines when needed. Railroad companies in the North generally cooperated with the government, so the law was rarely used. Stanton also secured the government's use of the telegraph. He moved the military's telegraph operations from McClellan's army headquarters to his department, a decision the general didn't like. This move gave Stanton more control over military communications, and he used it. Stanton made all members of the press work through Assistant Secretary Watson, where unwanted journalists were not allowed to see official government messages. If a journalist went elsewhere in the department, they would be charged with espionage (spying).

Before Stanton became War Secretary, President Lincoln gave responsibility for government security against betrayal to several cabinet members, mostly Secretary Seward, as he didn't trust Attorney General Bates or Secretary Cameron. Under Secretary Stanton, the War Department took over responsibility for internal security. A key part of Seward's strategy was using arbitrary arrests and detentions (arresting people without a clear reason), and Stanton continued this. Democrats strongly criticized these arrests, but Lincoln argued that his main job was to keep the government safe, and waiting for possible traitors to act would harm the government. At Stanton's request, Seward continued to detain only the most dangerous prisoners and released all others.

General-in-Chief

Lincoln eventually grew tired of McClellan's lack of action, especially after his order on January 27, 1862, to attack the Confederates in the East had little response from McClellan. On March 11, Lincoln removed McClellan from his position as general-in-chief of the entire Union army. McClellan was left in charge only of the Army of the Potomac, and Stanton replaced him. This created a bitter split between Stanton and McClellan. McClellan's supporters claimed Stanton "usurped" (took over illegally) the role of general-in-chief, saying a Secretary of War should be below military commanders. Lincoln ignored these calls, keeping military power with himself and Stanton.

Meanwhile, McClellan was preparing for the first major military operation in the East, the Peninsula Campaign. The Army of the Potomac began moving to the Virginia Peninsula on March 17. The first action was at Yorktown. Lincoln wanted McClellan to attack the town directly, but McClellan decided to lay siege to it instead after seeing the Confederate defenses. Politicians in Washington were angry about McClellan's delay. McClellan asked for more troops for his siege: the 11,000 men in Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin's division. Stanton wanted Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell's corps to stay together and march on Richmond, but McClellan insisted, and Stanton eventually gave in.

McClellan's campaign lasted several months. However, after Gen. Robert E. Lee became the commander of local Confederate forces on June 1, he launched attacks against the Army of the Potomac. By late June 1862, the Union army was only a few miles from the Confederate capital, Richmond. In addition, Stanton ordered McClellan to move one of his corps east to defend Washington. McClellan and the Army of the Potomac were pushed back to Harrison's Landing in Virginia, where Union gunboats protected them. In Washington, the press and public blamed Stanton for McClellan's defeat. On April 3, Stanton had stopped military recruiting because he mistakenly thought McClellan's campaign would end the war. With McClellan retreating and many casualties, the need for more men grew greatly. Stanton restarted recruiting on July 6, when McClellan's defeat was clear, but the damage was done. The press, angry about Stanton's strict rules for journalists, heavily criticized him, saying he was the only obstacle to McClellan's victory.

The attacks hurt Stanton, and he thought about resigning, but he stayed at Lincoln's request. As defeats continued, Lincoln tried to bring order to the scattered Union forces in Virginia. He decided to combine the commands of Maj. Gens. McDowell, John C. Frémont, and Nathaniel P. Banks into the Army of Virginia. This new army would be commanded by Maj. Gen. John Pope, who was brought east after success in the West. Lincoln also believed the North's army needed changes at the top. He and Stanton being the main commanders had proven too much, so Lincoln needed a skilled commander. He chose Gen. Henry W. Halleck. Halleck arrived in Washington on July 22 and was confirmed as the general-in-chief of Union forces the next day.

The War Continues

In late August 1862, Gen. Lee defeated Union forces at Manassas Junction in the Second Battle of Bull Run. This time, it was against Maj. Gen. Pope and his Army of Virginia. Many people, including Maj. Gen. Halleck and Secretary Stanton, thought Lee would then attack Washington. Instead, Lee began the Maryland Campaign. The campaign started with a small fight at Mile Hill on September 4, followed by a major battle at Harpers Ferry. Lincoln, without asking Stanton (perhaps knowing Stanton would object), combined Pope's Army of Virginia into McClellan's Army of the Potomac. With 90,000 men, McClellan led his army into the bloody Battle of Antietam and won, pushing Lee's Army of Northern Virginia back into Virginia. This effectively ended Lee's Maryland offensive.

McClellan's success at Antietam Creek made him bolder. He demanded that Lincoln and his government stop interfering with his plans, that Halleck and Stanton be removed, and that he be made general-in-chief of the Union Army. Meanwhile, he refused to aggressively pursue Lee's army, which was retreating. McClellan's unreasonable demands and delays continued, and Lincoln's patience wore thin. Lincoln removed him from leadership of the Army of the Potomac on November 5. Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside replaced McClellan a few days later.

Burnside, at Halleck's request, proposed a plan to create a diversion at Culpeper and Gordonsville, while his main force took Fredericksburg and then moved on to Richmond. Halleck's response on November 14 was: "The President has just assented to your plan. He thinks that it will succeed, if you move rapidly; otherwise not." The following Battle of Fredericksburg was a disaster, and the Army of the Potomac was easily defeated.

Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker replaced Burnside on January 26, 1863. Stanton didn't like Hooker much, as Hooker had openly criticized Lincoln's administration and had been disobedient while serving under Burnside. Stanton would have preferred Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans to lead the army, but Lincoln ignored Stanton's opinion. Lincoln chose Hooker because he had a reputation as a fighter and was popular at the time. Hooker spent a lot of time strengthening the Army of the Potomac, especially its morale. Hooker's only major battle with Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was the Battle of Chancellorsville in early May 1863. Lee had Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson attack Hooker's rearguard in a quick flanking move. Jackson's move was very skillful, leading to a Confederate victory on May 6, with 17,000 Union casualties.

Stanton tried to boost Northern spirits after the defeat, but news spread that under Hooker, the Army of the Potomac had become very undisciplined. Stanton asked for alcohol and women to be banned from Hooker's camps. Meanwhile, Lee was again moving into the North. Lee's movements worried Washington by mid-June, especially with disturbing reports from Hooker's officers. Like McClellan, Hooker kept overestimating Lee's numbers and said Lincoln's administration didn't fully trust him. Hooker resigned on June 27. Stanton and Lincoln decided that Maj. Gen. George Meade would replace him, and he was appointed the next day.

Lee and Meade first fought at the Battle of Gettysburg on July 1. News of a victory at Gettysburg and a great Confederate retreat came on July 4. Soon after, word came of Maj. Gen. Grant's victory at Vicksburg. Northerners were overjoyed. Stanton even gave a rare speech to a large crowd outside the War Department. However, the celebrations ended when Maj. Gen. Meade refused to attack Lee while the Army of Northern Virginia was stuck by the Potomac river. When Lee crossed the river untouched on July 14, Lincoln and Stanton were upset. Stanton wrote to a friend that Meade had "missed so great an opportunity of serving his country." Stanton knew, though, that Meade's hesitation came from his corps commanders, who used to outrank him.

While fighting in the East slowed down, it heated up in the West. After the two-day Battle of Chickamauga in late September, Maj. Gen. Rosecrans, commander of the Army of the Cumberland, was trapped in Chattanooga, Tennessee and surrounded by Gen. Braxton Bragg's forces. Rosecrans telegraphed Washington: "We have met a serious disaster." The situation in Chattanooga was desperate. The North needed to control the town. According to journalist Charles Anderson Dana, Stanton's assistant secretary since March 1863, Rosecrans might only last 15–20 more days, and without at least 20,000 to 25,000 more men, Chattanooga would be lost. Stanton organized the secret transportation of thousands of Union troops west by rail. Lincoln and Stanton agreed to make Maj. Gen. Grant the commander of almost all forces in the West. Grant could also fire Rosecrans and replace him with Maj. Gen. George Henry Thomas. Grant did this. In late November, Grant, with help from Thomas and Hooker, broke Gen. Bragg's siege at Chattanooga. Confederate Lt. Gen. James Longstreet tried to besiege Maj. Gen. Burnside's army at Knoxville, but Sherman moved east from Chattanooga, forcing the Confederates to retreat.

End of the War

Grant, now a lieutenant general and general-in-chief of the Union Army, crossed the Rapidan River on May 4, 1864. The next day, his and Lee's armies fought in the Battle of the Wilderness. The result was unclear, but Grant, unlike earlier commanders, refused to stop his advance. "There will be no turning back," he told Lincoln. Grant again fought Lee at Spotsylvania Court House, and again Union losses were much higher than Confederate losses. Several days later, Grant and Lee battled at Battle of Cold Harbor, where Grant launched many attacks in an open field, suffering heavy losses.

Nevertheless, Grant pushed on, secretly moving his army across the James River in a brilliant engineering feat. But he failed to take Petersburg, an important rail junction south of Richmond. The Union army had to stop attacking and began digging trenches. This started the Siege of Petersburg. "Long lines of parallel trenches curled south and east of Richmond as both armies dug in," historians Thomas and Hyman say. "Grant stabbed at Lee's fortifications, always keeping the pressure on, and at the same time probed westward, feeling for the railroads that brought Lee's supplies."

In the 1864 United States presidential election, Lincoln and his new Vice President, Andrew Johnson, won against their Democratic opponents, George B. McClellan and George H. Pendleton. Republicans also won many seats in Congress and governorships in Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and New York. Stanton played a big part in this victory. Several days before the election, he ordered soldiers from key states like Illinois, Lincoln's home state, to return home to vote. Stanton also used his powers at the War Department to make sure Republican voters were not bothered at the polls. Historians Thomas and Hyman credit Stanton's troop furlough (leave) and other actions for much of the Republican success in the 1864 elections.

On March 3, 1865, the day before Lincoln's second inauguration, Grant wired Washington that Lee had sent representatives to discuss peace. Lincoln initially told Grant to get peace with the South by any means necessary. Stanton, however, said it was the president's job to seek peace; otherwise, the president would be useless. This immediately changed Lincoln's tone. Stanton, at Lincoln's urging, told Grant that he was to "have no conference with General Lee unless it be for the surrender of Gen. Lee's army, or on some minor, and purely, military matter." Furthermore, Grant was not to "decide, discuss, or confer upon any political questions. Such matters the President holds in his own hands." Grant agreed.

Days later, Lincoln visited Grant at his siege headquarters (the Siege of Petersburg was still ongoing). Once Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan rejoined his army, Grant prepared his final push into Richmond. On April 1, 1865, Sheridan defeated Lee's army in the Battle of Five Forks, forcing a retreat from Petersburg. Stanton, who had stayed close to his telegraph for days, told his wife that evening: "Petersburg is evacuated and probably Richmond. Put out your flags." Stanton worried that President Lincoln, who had stayed to watch Grant's push into Richmond, was in danger of being captured, and warned him. Lincoln disagreed but was happy for Stanton's concern. The President wrote Stanton: "It is certain now that Richmond is in our hands, and I think I will go there to-morrow."

News of Richmond's fall, which came on April 3, caused huge excitement across the North. "The news spread fast, and people streaming from stores and offices speedily filled the thoroughfares. Cannons began firing, whistles tooted, horns blew, horsecars were forced to a standstill, the crowd yelled and cheered," say Thomas and Hyman. Stanton was overjoyed. At his command, candles were placed in the windows of each War Department building, while bands played "The Star-Spangled Banner." The department's headquarters were decorated with American flags and an image of a bald eagle holding a scroll with "Richmond" written on it. The night Richmond fell, Stanton tearfully gave a spontaneous speech to the crowd outside the War Department.

Lee and his army had slipped out of Richmond before it fell. Grant marched west to stop Lee's retreat, while Lincoln remained in Richmond. News of Grant's victories over the retreating Confederates filled Washington's telegraph lines. The Union Army was close behind Lee, capturing thousands of Confederate prisoners. On April 9, Lee finally surrendered, ending the war. On April 13, Stanton stopped conscription (drafting soldiers) and recruiting, as well as the army's purchasing efforts.

Lincoln Assassinated

On April 14, Lincoln invited Stanton, Grant, and their wives to join him at Ford's Theatre the next evening. Lincoln had invited Stanton to the theater several times, but Stanton always declined. Also, neither Stanton's nor Grant's wives would go unless the other went. The Grants used a visit to their children in New Jersey as their excuse. Finally, Lincoln decided to go to the theater with Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée. Stanton went home that night after visiting a sick Secretary Seward. He went to bed around 10 pm. Soon after, he heard Ellen yell from downstairs: "Mr. Seward is murdered!" Stanton rushed downstairs. Hearing that Lincoln might also be dead, Stanton became very agitated. He wanted to leave immediately. He was warned: "You mustn't go out ... As I came up to the house I saw a man behind the tree-box, but he ran away, and I did not follow him." Stanton paid little attention to the man; he found a taxi and went to Seward's home.

When he arrived, Stanton was told that Lincoln had indeed been attacked. Stanton ordered that the homes of all cabinet members and the Vice President be guarded. Stanton pushed through a crowd at Seward's home to find an unconscious Seward being treated by a doctor in a bloody third-floor room. Seward's son, Frederick, was left paralyzed by the attack. Stanton and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, who had arrived moments before, decided to go to Ford's Theatre to see the President. The two secretaries went by carriage, with Quartermaster General Meigs and David K. Cartter, a judge.

Stanton found Lincoln at the Petersen House across from the theater. Lincoln lay diagonally on a bed because of his height. When he saw the dying President, some accounts say Stanton began to cry. However, William Marvel states in his book, Lincoln's Autocrat: The Life of Edwin Stanton, that "Stanton's emotional detachment and his domineering persona made him valuable that night, as others wallowed in anguish." Historians Thomas and Hyman also state: "Always before, death close at hand had unsettled him close to the point of imbalance. Now he seemed calm, grim, decisive, in complete outward control of himself." Andrew Johnson, about whom Stanton and the country knew little, was sworn in as President at 11 am on April 15, at the Kirkwood Hotel. However, Stanton, who had planned to retire after the war, "was indeed in virtual control of the government," say Thomas and Hyman. "He had charge of the Army, Johnson was barely sworn in and vastly unsure of himself, and Congress was not in session."

Stanton ordered statements taken from those who saw the attack. Witnesses blamed actor John Wilkes Booth for the assassination. Stanton put all soldiers in Washington on alert and ordered a lockdown of the city. Rail traffic to the south was to be stopped, and fishing boats on the Potomac were not to come ashore. Stanton also called Grant back to the capital from New Jersey.

On April 15, Washington was, as journalist George A. Townsend said, "full of Detective Police." At Stanton's request, the New York Police Department joined the War Department's detectives in their tireless search for Booth and any helpers. Stanton had the lower deck of the monitor USS Montauk, near the Washington Navy Yard, hold several of the conspirators: Lewis Powell, Michael O'Laughlen, Edmund Spangler, and George Atzerodt. The other plotters, except Booth and Mary Surratt, were held aboard the USS Saugus. The prisoners on both boats were bound with ball and chain, with handcuffs attached to an iron rod. Stanton also ordered bags placed over the captives' heads, with a hole for eating and breathing. Surratt was kept at Old Capitol Prison. Booth, the main culprit, was shot in a barn in Virginia by Boston Corbett and died soon after. Booth's body was put aboard the Montauk. After an autopsy confirmed Booth's identity, he was buried in a "secret, unmarked" grave, on Stanton's orders. Stanton knew Booth would be praised in the South and wanted to prevent that. The conspirators were later tried and found guilty. Most of them faced severe consequences.

Johnson Administration (1865–1868)

Sherman's Truce

Lt. Gen. Grant, unable to find Stanton at the War Department, sent a note to his home on the evening of April 21. The matter was urgent. Maj. Gen. Sherman, whose army headquarters were in Raleigh, North Carolina, had negotiated a peace deal with Confederate commander Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, with the approval of Confederate States Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge. Sherman had only been allowed to negotiate with Southerners on military matters, just as Grant had been with Lee. Sherman knew his talks were supposed to be strictly military, but he ignored these limits.

Sherman's deal included ending fighting with the South. But it also said that Southern governments that had rebelled against the U.S. would be recognized by the federal government once they swore loyalty. The deal also allowed federal courts to be restarted in rebellious states, restored property and voting rights to Southerners, and gave a general pardon to Southerners who had rebelled. The deal even allowed Southern troops to give their weapons to their state governments, which would effectively rearm the Southern states. Sherman's truce also gave power to the Supreme Court to settle disagreements between state and local governments in the South. This was a political issue, not a legal one, so the court didn't constitutionally have that power.

The messenger arrived at Stanton's home, out of breath, interrupting his dinner. When he heard the news, Stanton, "in a state of high excitement," rushed to the War Department. He sent for all cabinet members in the President's name. Johnson's cabinet, along with Grant and Preston King, Johnson's advisor, met at 8 pm that night. Everyone present strongly condemned Sherman's actions. President Johnson told Stanton to inform Sherman that his deal was rejected. He also said that "hostilities should be immediately resumed after giving the Confederates the forty-eight hours' notice required to terminate the truce." Grant would go to Raleigh at once to tell Sherman about Stanton's order and to take command of troops in the South.

Stanton shared the matter with the press. Besides revealing the details of Sherman's deal, Stanton said Sherman had intentionally ignored direct orders from both Lincoln and Johnson. He listed nine reasons why Sherman's deal was completely rejected. Stanton also accused Sherman of carelessly allowing Jefferson Davis to flee the country with gold that Davis supposedly took after leaving Richmond. This last claim was based on Sherman moving Maj. Gen. George Stoneman's forces away from the Greensboro railway, which was where Davis and other Confederate officials had fled. Stanton's words were very harsh. "It amounted to a strong criticism of Sherman and practically accused him of disloyalty," say Thomas and Hyman. Also, since Sherman was one of the most respected generals, Stanton's public statement put his position in the administration at risk.

Not having seen Stanton's message to the press, Sherman wrote Stanton a friendly letter, calling his agreement "folly." He said that even though he still felt his deal with Johnston and Breckinridge was good, it wasn't his place to argue with his superior's decision, and he would follow orders. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Halleck, at Grant's request, told several of Sherman's officers to move their forces to North Carolina, no matter what Sherman said. Halleck sent another message telling Sherman's generals not to listen to Sherman's orders at all. After Halleck's order and reading Stanton's message to the press in a newspaper, Sherman became extremely angry. Sherman felt Stanton had unfairly called him disloyal. "I respect [Stanton's] office but I cannot him personally, till he undoes the injustice of the past," Sherman told Grant. Sherman's brother, Senator John Sherman, wanted the general criticized for his actions but still treated fairly. Sherman himself, and his wife's powerful family, the Ewings, wanted Stanton to publicly take back his statements. Stanton, as usual, refused.

In late May, there was a Grand Review of the Armies, where the Union Army paraded through Washington. Halleck offered Sherman a place to stay at his home, but the general flatly refused. He told Grant that he would only listen to orders from Stanton if they were clearly approved by the President. Sherman also stated that "retraction or cowardly excusing" would no longer be enough. The only thing acceptable to Sherman would be for Stanton to declare himself a "common libeller" (someone who spreads false, damaging statements). "I will treat Mr. Stanton with similar scorn and contempt, unless you have reasons otherwise, for I regard my military career as ended, except as needed to put my army into your hands."

Sherman kept his promise. At the Grand Review, Sherman saluted the President and Grant, but he ignored the Secretary of War by walking past him without a handshake, in full view of the public. Stanton showed no immediate reaction. Journalist Noah Brooks wrote, "Stanton's face, never very expressive, remained immobile." This insult led to rumors that Stanton was about to resign. Stanton also thought about leaving his job, but at the request of the President and many others, including people in the military, he stayed. To make amends, Sherman's wife brought the Stantons flowers and spent time at their home, but Sherman continued to hold a grudge against Stanton.

Reconstruction Era

The war was over, and Stanton now had the big job of changing the American military so it could work well in peacetime, just as it had during the war. In the North, Stanton reorganized the army into two parts: one for "training and ceremonial duties," and another to deal with the American Indians in the west, who were restless after the war. In the South, a high priority was filling the power vacuum left after the rebellion. Stanton presented his plan for military occupation, which Lincoln had supported, to the President. It involved setting up two military governments in Virginia and North Carolina, with military police to enforce laws and keep order.

President Johnson had promised his Cabinet in their first meeting on April 15 that he would follow Lincoln's plans for Reconstruction. Lincoln had discussed these plans in detail with Stanton. On May 29, 1865, Johnson issued two announcements. One appointed William Woods Holden as the temporary governor of North Carolina. The other pardoned individuals involved in the rebellion, with a few exceptions, if they agreed to be loyal and accept all laws about slavery. Johnson also recognized Francis Harrison Pierpont's government in Virginia, as well as the governments in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Tennessee, which were formed under Lincoln's "ten percent plan" (a plan for states to rejoin the Union). Johnson also offered the ten percent plan to several other Southern states.

In his 1865 message to Congress, the Democratic Johnson argued that the only proof of loyalty a state needed to show was ratifying the Thirteenth Amendment (which abolished slavery). Republicans in Congress disagreed. Senator Charles Sumner and Representative Thaddeus Stevens thought black suffrage (the right for Black men to vote) was very important for the nation's security and for the Republican Party to stay strong. Republicans used parliamentary rules to make sure none of the Southern delegates, who were mostly former Confederate leaders, could take seats in Congress. They also set up a mostly Republican committee to decide on Reconstruction matters.

On Reconstruction, the President and Congress were very divided. Johnson, even when his pardon policy was heavily criticized, stubbornly supported and continued it. However, Radical Republicans in Congress preferred Stanton's military occupation plan. The President's support from moderate Republicans decreased after the terrible anti-Black riots in Memphis and New Orleans. The public also seemed to be against Johnson. In the 1866 congressional elections, Republicans gained many seats from their Democratic rivals. In both the House and Senate elections, Republicans won more than two-thirds of the seats.

In the new year, some Republicans wanted to use their majority to remove Johnson. They introduced the Tenure of Office Bill, written with Stanton in mind. The President had long thought about firing Stanton and replacing him with Maj. Gen. Sherman. The Tenure of Office Bill would have made this illegal without the approval of Congress, which was unlikely for Stanton, who was strongly supported by and working with Radical Republicans. When the bill reached the President's desk, he vetoed it. His veto was overridden the same day.

With the protection of the Tenure of Office Act, Stanton's opposition to Johnson became more open. In the following months, Johnson grew more and more frustrated with his War Secretary. Johnson told Grant he planned to remove Stanton and give him the War Secretary job. Grant opposed the idea. He argued for Stanton to stay and said the Tenure of Office Act protected Stanton. Grant also said that if the law proved ineffective, public opinion would turn even more against the administration. Seward, who still greatly respected Stanton, also disagreed with his removal. The words of Grant and Seward made Johnson hesitate. However, his resolve was strengthened by support from Secretary Welles and Salmon Chase, now the Supreme Court's Chief Justice. On August 12, 1867, Johnson sent a note to Stanton saying he was suspended from his position and was to hand over the department's files and power to Grant. As required by the Tenure of Office Act, he also notified the Senate. Stanton reluctantly, but with little resistance, complied.

Impeachment Trial

On January 13, 1868, the Senate voted strongly to put Stanton back as Secretary of War. Grant, fearing the law's penalty of $10,000 in fines and five years in prison, and especially because he was likely to be the Republican presidential candidate, immediately handed the office back. Stanton returned to the War Department soon after, in "unusually fine spirits and chatting casually," as newspapers reported. His return brought many congratulatory messages, thanking him for opposing the unpopular Johnson. The President, meanwhile, again looked for someone suitable to lead the War Department. But after a few weeks, he seemed to accept Stanton's return. However, he tried to reduce the power of Stanton's office, often ignoring it. Still, with his ability to sign treasury warrants and his support from Congress, Stanton held significant power.

Johnson became focused on bringing about Stanton's downfall. "No longer able to bear the congressional insult of an enemy imposed on his Official family," Marvel says, "Johnson began to ponder removing Stanton outright and replacing him with someone acceptable enough to win Senate approval." Johnson sought Lorenzo Thomas, the army's adjutant general, to replace Stanton, and Thomas agreed. On February 21, Johnson told Congress he was firing Stanton and appointing Thomas as temporary secretary. Stanton, urged by Republican senators, refused to leave his post. That night, Republicans in the Senate, despite Democratic resistance, passed a resolution declaring Stanton's removal illegal. In the House, a motion was presented to impeach Johnson. On February 24, the motion was agreed to, and Johnson was impeached by a party-line vote of 126 to 47.

Johnson's trial began in late March. With a mostly Republican Senate, many thought Johnson's conviction was a sure thing. However, during the process, several senators began to hesitate about removing the President. Stanton, meanwhile, had stayed locked in the War Department's headquarters for weeks, only sneaking out occasionally to visit his home. When it seemed to Stanton that Johnson would not forcefully remove him, he started spending more time at home. Stanton watched closely as the trial, which he was sure would end with Johnson's conviction, continued for several months. When it was time to vote, 35 senators voted to convict, and 19 to acquit. This was one vote short of the 36-vote supermajority needed for a conviction. The remaining proceedings were delayed for several days for the Republican National Convention. On May 26, after Johnson had been found not guilty on all ten other charges, Stanton submitted his resignation to the President.

Later Years and Death

Campaigning in 1868

After Johnson was found not guilty and Stanton resigned, Johnson's administration spread the idea that those who wanted his impeachment were bad, especially Stanton. However, Stanton left office with strong public and Republican support. In other ways, though, Stanton was in trouble. His health was very poor due to his hard work during and after the war, and he didn't have much money. After resigning, Stanton only had the rest of his salary and a $500 loan. Stanton refused requests from fellow Republicans to run for the Senate, choosing instead to go back to his law practice.

Stanton's law efforts paused when Robert C. Schenck, the Republican candidate for one of Ohio's House of Representatives seats, asked for his help in August 1868. Schenck's opponent, Democrat Clement Vallandigham, was known among Republicans for his anti-war views and disliked by Stanton. Believing that a Democratic victory at any level would harm the results of the war and undo Republican efforts, Stanton toured Ohio to campaign for Schenck, other Ohio Republicans, and Grant, the Republican presidential candidate. Meanwhile, Stanton's health continued to get worse. His doctor warned him against making long speeches because his asthma severely bothered him. Stanton's illness forced him to return to Washington in early November. His weak state was replaced by excitement when Republicans won the Schenck–Vallandingham race and the presidential election.

Health Worsens

Afterward, Stanton took on a case in Pennsylvania federal court involving disputed lands in West Virginia, worth millions of dollars because of their coal and timber. By this time, Stanton's illness was very clear. He became so sick that papers for the case had to be delivered to him at his home. The court ruled against Stanton's client, but Stanton won an appeal at the U.S. Supreme Court to have the case sent back to the lower court. At Christmas, Stanton couldn't go downstairs, so the family celebrated in his room.

Many people thought at the time that Grant, who had largely ignored Stanton for several months, would reward him for his campaigning efforts. Stanton, however, said that if a position in Grant's administration were offered, he would refuse it. Ohio congressman Samuel Shellabarger wrote: "[Stanton] says he has not a great while to live & must devote that to his family..." Early in the new year, Stanton was preparing for his death. However, when spring arrived, Stanton's condition improved. When the healthier Stanton appeared at a congressional inquiry, talks of Grant rewarding Stanton resumed. Some thought Stanton would be a good ambassador to England; instead, Grant offered Stanton a diplomatic mission to Mexico, which he declined.

Stanton's health changed throughout 1869. In the latter half of the year, after hearing that Congress had created a new associate justice seat on the Supreme Court, Stanton decided he would try to convince Grant to name him to that position. Stanton used Grant's close friend, Bishop Matthew Simpson, to persuade Grant of his suitability for a place on the Supreme Court. However, Grant chose Attorney General Ebenezer R. Hoar for the seat on December 14, 1869. The next day, Associate Justice Robert Cooper Grier announced his resignation, effective February 1, 1870, creating another vacancy for Grant to fill.

Petitions supporting Stanton for the Supreme Court vacancy were circulated in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. They were delivered to the president on December 18, 1869. Grant and Vice President Colfax went to Stanton's home to personally offer the nomination on December 19, Stanton's 55th birthday. Grant officially submitted the nomination to the Senate on December 20, and Stanton was confirmed that same day by a vote of 46–11. Stanton wrote a letter accepting the confirmation the next day, but he died before he could start his job as an associate justice.

Death and Funeral

On the night of December 23, Stanton complained of pains in his head, neck, and spine. His doctor, Surgeon General Joseph Barnes, was called. As on many nights before, Stanton's asthma made breathing difficult. Stanton's lungs and heart felt tight, which kept his wife and children, as well as Barnes, by his bedside. Stanton's condition began to improve at midnight, but then he started "gasping so strenuously for air that someone ran for the pastor of the Church of the Epiphany, and soon after he arrived Stanton lost consciousness." Around 3 am, Barnes checked Stanton's pulse and breathing but felt nothing. Stanton died on December 24, 1869, at the age of 55.

Stanton's body was placed in a black, linen-lined coffin in his second-story bedroom. President Grant had wanted a state funeral, but Ellen Stanton wanted a simpler ceremony. Nevertheless, Grant ordered all public offices closed, and federal buildings draped in "raiments of sorrow" (black cloth). Flags in several major cities were lowered to half-staff, and gun salutes sounded at army bases around the country. On December 27, his body was carried by artillerymen to his home's parlor. President Grant, Vice President Schuyler Colfax, the Cabinet, the entire Supreme Court, senators, representatives, army officers, and other important officials all attended Stanton's funeral. After the eulogy (a speech praising the deceased), Stanton's casket was placed on a caisson (a two-wheeled cart) and pulled by four horses to Washington D.C.'s Oak Hill Cemetery at the head of a mile-long procession.

Stanton was buried next to his son James Hutchinson Stanton, who had died as a baby several years earlier. Various Cabinet officials, generals, justices, and senators carried Stanton's coffin to its final resting place. One of Stanton's professors from Kenyon College performed a service at the graveyard, and a three-volley salute was fired, ending the ceremony.

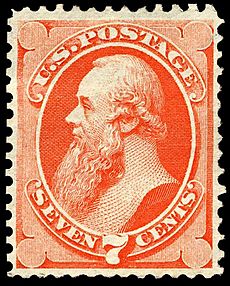

Stanton on U.S. Postage

Edwin Stanton was only the second American, other than a U.S. President, to appear on a U.S. postage stamp. The first was Benjamin Franklin in 1847. The only Stanton stamp was released on March 6, 1871. This was also the only stamp issued by the post office that year. The 7-cent Stanton stamp paid the postage for letters sent from the U.S. to various countries in Europe.

Legacy

A special engraved picture of Stanton appeared on U.S. paper money in 1890 and 1891. These bills are called "treasury notes" or "coin notes" and are highly sought after by collectors today. Many people consider these rare notes to be some of the best examples of detailed engraving ever seen on banknotes. The $1 Stanton "fancyback" note from 1890 is ranked number 83 in the "100 Greatest American Currency Notes." Stanton also appears on the fourth issue of Fractional currency, on the 50-cent note. Stanton Park, located four blocks from the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C., is named after him, as is Stanton College Preparatory School in Jacksonville, Florida.

A steam engine built in 1862 was named the "E. M. Stanton" in honor of the new Secretary of War. Stanton County, Nebraska, is named for him. Stanton Middle School in Hammondsville, Ohio, is named after him. A neighborhood in Pittsburgh is named for him (Stanton Heights), as well as its main road (Stanton Avenue). Stanton Park and Fort Stanton in Washington, D.C., were named for him, as was Edwin Stanton Elementary School in Philadelphia. Edwin L. Stanton Elementary School in Washington, DC, was named for his son, who served as the Secretary of the District of Columbia.

Images for kids

-

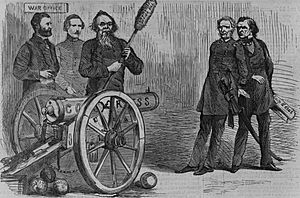

"The Situation", a Harper's Weekly cartoon gives a humorous breakdown of "the situation". Stanton aims a cannon labeled "Congress" on the side at President Andrew Johnson and Lorenzo Thomas to show how he was using Congress to defeat the president and his unsuccessful replacement. He also holds a ramrod marked "Tenure of Office Bill" and cannonballs on the floor are marked "Justice". Ulysses S. Grant and an unidentified man stand to Stanton's left.

See also

In Spanish: Edwin M. Stanton para niños

In Spanish: Edwin M. Stanton para niños

- List of United States political appointments that crossed party lines