Simon Cameron facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Simon Cameron

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| United States Senator from Pennsylvania |

|

| In office March 4, 1867 – March 12, 1877 |

|

| Preceded by | Edgar Cowan |

| Succeeded by | J. Donald Cameron |

| In office March 4, 1857 – March 4, 1861 |

|

| Preceded by | Richard Brodhead |

| Succeeded by | David Wilmot |

| In office March 13, 1845 – March 3, 1849 |

|

| Preceded by | James Buchanan |

| Succeeded by | James Cooper |

| United States Minister to Russia | |

| In office June 25, 1862 – September 18, 1862 |

|

| President | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | Cassius Clay |

| Succeeded by | Cassius Clay |

| 26th United States Secretary of War | |

| In office March 5, 1861 – January 14, 1862 |

|

| President | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | Joseph Holt |

| Succeeded by | Edwin Stanton |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 8, 1799 Maytown, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | June 26, 1889 (aged 90) Maytown, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (before 1849) American (1849–1856) Republican (1856–1877) |

| Spouse |

Margaret Brua

(m. 1822) |

| Children | 10, including J. Donald |

| Signature | |

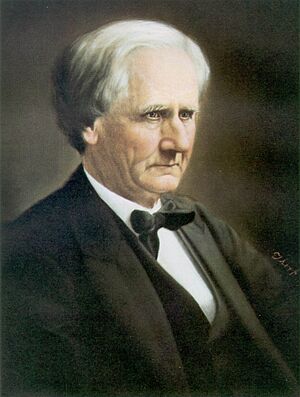

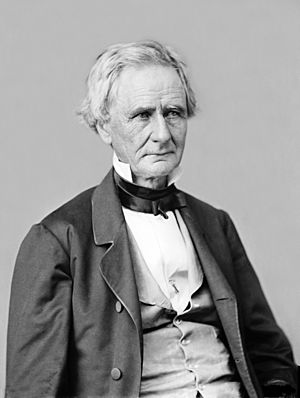

Simon Cameron (March 8, 1799 – June 26, 1889) was an American businessman and politician. He represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate three times. He also served as United States Secretary of War under President Abraham Lincoln at the start of the American Civil War.

Cameron was born in Maytown, Pennsylvania. He became very rich from railways, canals, and banking. He was first elected to the Senate in 1845 as a Democrat. Cameron was against slavery. He briefly joined the Know Nothing Party before becoming a Republican in 1856. He won another Senate term in 1857. He helped Abraham Lincoln get nominated at the 1860 Republican National Convention.

Lincoln chose Cameron as his first Secretary of War. Cameron's time in this role had problems, including claims of poor management. He was then sent to be the Ambassador to Russia in 1862. After the Civil War, Cameron returned to politics. He won a third Senate election in 1867. He built a strong political group called the Cameron machine. This group controlled Pennsylvania politics for the next 70 years.

Contents

Early Life and First Jobs

Simon Cameron was born in Maytown, Pennsylvania, on March 8, 1799. His parents were Charles and Martha Cameron. His grandfather, also named Simon, came from Scotland in 1765. He was a farmer and fought in the American Revolutionary War. Simon was the third of eight children.

His father, Charles, was a tailor and tavern keeper, but he was not very successful. When Simon was young, his father died. Simon went to live with Dr. Peter Grahl, a Jewish doctor in Sunbury. The Grahls treated him like their own son. Simon read many books in their library and learned a lot.

When he was 17, Cameron became a printer's helper. He worked for a newspaper called the Sunbury and Northumberland Gazette. Later, he moved to Harrisburg, the capital of Pennsylvania. There, he worked for the Pennsylvania Republican, a major newspaper. After two years, he became an assistant editor.

Working for a Harrisburg newspaper meant being involved in politics. Cameron said he attended almost every meeting of the Pennsylvania General Assembly (the state legislature) since 1817. He met Samuel D. Ingham, a state official. Ingham hired Cameron to edit his newspaper, the Doylestown Messenger, in 1821. This job did not last long, as the paper was not making money.

Cameron then worked as a compositor for the Congressional Globe. This paper reported on debates in Congress. This job helped him meet important national leaders like President James Monroe. In 1822, he returned to Harrisburg and became a partner in the Pennsylvania Intelligencer. He also bought another paper, the Republican, and combined them. This gave him enough money to marry Margaret Brua on October 16, 1822. They had ten children, and six lived to be adults.

Starting in Politics

Cameron's friend, John Andrew Shulze, became Pennsylvania's governor in 1823. This helped Cameron a lot. For several years, Cameron had a good job as the State Printer. In 1829, Governor Shulze made him Adjutant-General of Pennsylvania. This job gave him the title of "general," which he used for the rest of his life.

After this, Cameron stopped being a journalist. He sold his newspaper interests. He made sure his brother, James, got the state printing contracts. Governor Shulze also gave Cameron contracts to build canals in Pennsylvania.

Cameron was a delegate for the Democratic-Republican Party in 1824. He slowly began to support General Andrew Jackson for president. Jackson won the election in 1828. Cameron's support for Jackson grew during Jackson's first term. Cameron was busy with his own businesses, like founding the Bank of Middletown and building canals and railroads.

Jackson found Cameron to be a helpful person in Pennsylvania. When Jackson decided to run for president again in 1832, Cameron helped get the Pennsylvania legislature to support him. Cameron also helped Martin Van Buren become Jackson's running mate. As a reward, Cameron was appointed to the Board of Visitors for the United States Military Academy at West Point. By the mid-1830s, Cameron was well-known in the Democratic Party.

Cameron helped his friend James Buchanan get elected to the Senate in 1834. This made Cameron more important in Washington. In 1837, Cameron was appointed a commissioner for a treaty with the Winnebago Indians. This treaty involved payments to the tribe. There were some questions about how the money was handled. This led to people calling Cameron the "Great Winnebago Chief," which made him angry.

After this, Cameron continued to support Buchanan. In 1844, Cameron helped make sure that Martin Van Buren did not get the Democratic presidential nomination. Cameron was not excited about the final nominee, James K. Polk. Polk won the presidency, but Cameron did not work very hard for him.

First Term as Senator (1845–1849)

Becoming a Senator

In January 1845, Pennsylvania needed to elect a new senator. The Democratic Party was divided. Cameron worked to get support from a minority of Democrats, plus the Whigs and the Native American Party (also called Know Nothings). These groups liked Cameron because he supported high tariffs (taxes on imported goods) and improving transportation.

On March 13, 1845, Cameron was elected senator. He won with votes from Democrats who disagreed with their party, and from the Whigs and Know Nothings. Many mainstream Democrats were very angry. They said Cameron won by unfair means. This caused a growing disagreement between Cameron and James Buchanan.

Key Events as Senator

Cameron started his first Senate term without strong support from either major party. President Polk did not ask Cameron for advice on federal jobs in Pennsylvania. Cameron became angry and blocked some of Polk's choices for jobs. He also helped stop Polk's choice for the Supreme Court.

Cameron and Polk also disagreed on tariffs. Cameron spoke strongly against the Walker tariff in July 1846. He said it would hurt Pennsylvania's iron factories. The bill passed anyway, but Polk never forgave Cameron.

Cameron supported the annexation of Texas and the Mexican–American War. However, he did not want slavery to spread into new lands gained from Mexico. He supported the Wilmot Proviso, which would ban slavery in these new areas. He believed each state or territory should decide on slavery, but he wanted to limit its spread. He thought Southern states would eventually end slavery on their own.

Cameron's Senate term ended in 1849. Many Democrats still disliked how he had been elected. The Whigs won control of the state legislature. Cameron did not get any votes in the election for senator. James Cooper, a Whig, was elected instead.

Out of Office (1849–1857)

After his Senate term, Cameron focused on his businesses, like railroads and banking. He still stayed involved in politics. He hoped to return to the Senate in 1851, but he did not get enough votes. However, the new senator, Richard Brodhead, became his political friend.

Cameron and James Buchanan continued to disagree. Cameron tried to hurt Buchanan's chances for the 1852 Democratic presidential nomination. He sent an old newspaper article to a senator, showing Buchanan had signed an anti-slavery petition. Buchanan's friends in the newspapers attacked Cameron in return. The nomination went to Franklin Pierce.

In 1854, the Kansas–Nebraska Act caused many problems for the Democratic Party in the North. Cameron saw a chance to return to power. He worked with the Know Nothings, who were against immigration and the spread of slavery. In 1855, Cameron was the choice of the Know Nothing group for senator. However, the legislature was deadlocked, and no senator was chosen that year.

Second Term as Senator (1857–1861)

1857 Election

By 1856, groups against the Democrats and the Kansas-Nebraska Act started to form the Republican Party. Cameron joined this new party. He saw it as a way to get back into the Senate. He attended the 1856 Republican National Convention that nominated John C. Frémont for president. Cameron was considered as Frémont's running mate.

The Democrats had a small majority in the Pennsylvania legislature. Cameron worked secretly with some Democrats who disliked Buchanan. He also got Republicans and Know Nothings to support him. On January 13, 1857, Cameron was elected senator by just one vote. This shocked many people. The three Democrats who voted for Cameron were punished and lost their next elections. Cameron's son, Donald, was the first to tell his father the news.

Many Democrats said Cameron won by bribery. The legislature and the Senate investigated, but found no proof of wrongdoing. Still, like the Winnebago affair, this election gave Cameron a reputation for being involved in questionable deals.

Leading Up to the Civil War

Cameron quickly became an important leader for the Republicans in the Senate. The Senate was deeply divided over slavery. Cameron still kept friendships with senators from the South. He opposed the spread of slavery, believing it was bad for Pennsylvania. But he thought Congress could not stop slavery where it already existed.

Around 1859, Cameron hired an escaped slave named Tom Chester as a servant. Cameron helped him get an education. Chester later moved to Liberia and became its ambassador to Russia.

Cameron campaigned for Republicans in Pennsylvania. His influence helped them win control of the state House of Representatives in 1858. By 1859, his status in Pennsylvania politics grew even more.

1860 Election

Presidential Nomination

In 1860, Cameron wanted to be the Republican candidate for president. He thought Pennsylvania's strong support would help him win. Some people thought he might support William H. Seward, another candidate. Cameron hosted both Seward and Salmon P. Chase in 1859. This showed he wanted to stay friendly with all the main candidates.

In February 1860, Pennsylvania Republicans supported Cameron as their "favorite son" candidate. They also chose Andrew Curtin for governor. Cameron and Curtin did not like each other, but they did not want to split the party.

At the 1860 Republican National Convention in Chicago, candidates worked to stop Seward from winning right away. They chose Abraham Lincoln as the candidate with the most support. Lincoln's team made promises to get votes, including to Cameron's supporters. It is believed they promised Cameron a spot in the cabinet.

On the first vote, Pennsylvania gave most of its votes to Cameron. On the second and third votes, Pennsylvania's votes went to Lincoln, helping him win the nomination.

Campaign

The promise to Cameron became public. Some newspapers said he would be Secretary of the Treasury. Cameron strongly supported Lincoln during the campaign. He wrote to Lincoln, promising that Pennsylvania would vote for him. Cameron also sent $800 to Lincoln's campaign. Lincoln showed Cameron some of his old speeches about tariffs, which pleased Cameron.

On October 9, 1860, Pennsylvania held state elections. Curtin easily won governor, and Republicans gained more seats in the legislature. This meant a Republican would replace Senator Bigler. If Cameron took a high job, another Republican would take his Senate seat. On Election Day, November 6, 1860, Pennsylvania voted for Lincoln. Cameron sent a telegram to Lincoln saying, "Pennsylvania, 70,000 for you. New York safe, Glory enough."

Secretary of War

Appointment

At first, Lincoln did not plan to include Cameron in his cabinet. Many letters came to Lincoln, urging him to make Cameron Secretary of the Treasury. Lincoln's advisor, Leonard Swett, told Cameron that Lincoln was not bound by any promises.

Cameron met with Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois, in December 1860. Lincoln offered Cameron a place in the cabinet, either as Secretary of the Treasury or of War. Lincoln gave Cameron the offer in writing. But soon after, Lincoln received many messages against Cameron. People mentioned the Winnebago affair and claims of bribery. One person wrote, "He is corrupt beyond belief." Lincoln then wrote to withdraw the offer.

Cameron complained to Lincoln's friends but said nothing publicly. He even arranged for Lincoln and his family to use a fancy train car for their trip to Washington. Lincoln was in a difficult spot. He felt Pennsylvania deserved a cabinet spot, and many people wanted Cameron.

Lincoln decided not to offer Cameron the Treasury job, but kept open the idea of another role. Cameron kept showing the first letter where Lincoln offered him a job, without showing the letter that took it back. Lincoln was still unsure when he left for Washington. In Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, Cameron's supporters kept pushing Lincoln to appoint him.

Finally, Cameron's opponents in Pennsylvania agreed to his appointment. After much thought, Lincoln decided to appoint Cameron to the cabinet. Cameron wanted the Treasury job, but it went to Salmon P. Chase. Cameron reluctantly accepted the War Department. On March 5, 1861, Lincoln nominated Cameron to be Secretary of War.

Cameron disagreed with Lincoln and openly said that enslaved people should be freed and allowed to join the army. Lincoln was not ready to say this publicly at the time. Cameron's time as Secretary of War was known for claims of poor management.

Time in Office

Cameron became Secretary of War on March 12, 1861. At a cabinet meeting on March 15, Lincoln asked about Fort Sumter. Cameron said the fort, which was in Charleston, South Carolina (a state that had left the Union), should not be resupplied. He felt it could not be held.

On April 18, 1861, after Virginia left the Union, the Virginia militia took Harpers Ferry. This was an important railroad hub. The president of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) asked Cameron to protect his railroad. But Cameron warned him that if any Confederate troops used his line, it would be treason. Cameron agreed to protect other railroads, but not the B&O. The B&O had to pay for its own repairs and often did not get paid by the government.

In June 1861, Confederate General Stonewall Jackson seized Martinsburg, another B&O station. Jackson began taking B&O trains and tracks for the Confederacy. The B&O's main line to Washington was out of service for over six months. Other railroads, like the Pennsylvania Railroad, made money from the extra traffic.

These problems caused coal prices to rise in Washington during winter. Farmers in the West could not get their crops to market. The president of another railroad told newspapers that the War Department was treating the B&O unfairly.

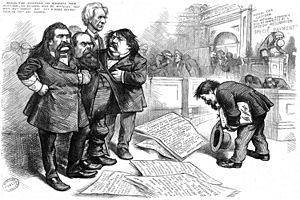

Cameron's management problems became well-known. Pennsylvania Representative Thaddeus Stevens once joked that Cameron would not even steal a "red hot stove." Cameron demanded Stevens take back the insult. Stevens then told Lincoln, "I believe I told you he would not steal a red hot stove. I will now take that back."

In January 1862, President Lincoln replaced Cameron with Edwin M. Stanton. Stanton was a Pennsylvania lawyer who had been Cameron's legal advisor. After this, Cameron became the Minister to Russia.

Later Political Career

After the American Civil War, Cameron made a political comeback. He built a very strong state Republican political machine. This group controlled Pennsylvania politics for the next 70 years. In 1866, Cameron was elected to the Senate again.

Cameron convinced his friend, President Ulysses S. Grant, to appoint his son, J. Donald Cameron, as Secretary of War in 1876. Later that year, Cameron helped Rutherford B. Hayes win the Republican nomination for President. Cameron resigned from the Senate in 1877. He made sure his son took his place as senator.

In the 1880 United States presidential election, Cameron and his son supported Ulysses S. Grant for a third presidential term. However, their group did not succeed. James A. Garfield won the Republican nomination and then the presidency.

Personal Life and Death

Cameron's brother, James, was a Colonel in the army. He was killed in action at the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861.

Simon Cameron retired to his farm near Maytown, Pennsylvania. He died there on June 26, 1889, at the age of 90. He is buried in the Harrisburg Cemetery in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Legacy

Historians say Cameron was one of the most successful political bosses in American history. He was smart, rich, and used his skills to build a powerful Republican organization. He became the clear leader of Pennsylvania politics. He was good at business and truly cared about Pennsylvania's interests. He was also skilled at managing politicians.

Cameron rewarded his friends and punished his enemies. He also kept good relationships with Democrats. His reputation for being unfair was often exaggerated by his enemies. He was in politics for power, not just for money.

Cameron County, Pennsylvania, and Cameron Parish, Louisiana, are named after him. Also named in his honor are:

- Simon Cameron House and Bank, Middletown, Pennsylvania

- Simon Cameron House, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

- Simon Cameron School, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

See also

In Spanish: Simon Cameron para niños

In Spanish: Simon Cameron para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |