Franklin Pierce facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Franklin Pierce

|

|

|---|---|

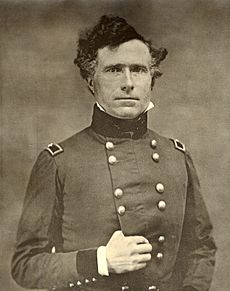

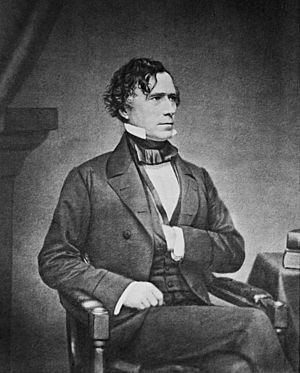

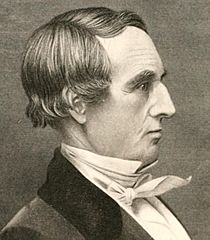

Portrait by Mathew Brady, c. 1855–1865

|

|

| 14th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1853 – March 4, 1857 |

|

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by | Millard Fillmore |

| Succeeded by | James Buchanan |

| United States Senator from New Hampshire |

|

| In office March 4, 1837 – February 28, 1842 |

|

| Preceded by | John Page |

| Succeeded by | Leonard Wilcox |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New Hampshire's at-large district |

|

| In office March 4, 1833 – March 3, 1837 |

|

| Preceded by | Joseph Hammons |

| Succeeded by | Jared W. Williams |

| Speaker of the New Hampshire House of Representatives | |

| In office January 5, 1831 – January 2, 1833 |

|

| Preceded by | Samuel C. Webster |

| Succeeded by | Charles G. Atherton |

| Member of the New Hampshire House of Representatives from Hillsborough |

|

| In office January 7, 1829 – January 2, 1833 |

|

| Preceded by | Thomas Wilson |

| Succeeded by | Hiram Monroe |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 23, 1804 Hillsborough, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Died | October 8, 1869 (aged 64) Concord, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Resting place | Old North Cemetery Concord, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives | Benjamin Kendrick Pierce (brother) |

| Education |

|

| Profession |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank |

|

| Battles/wars | |

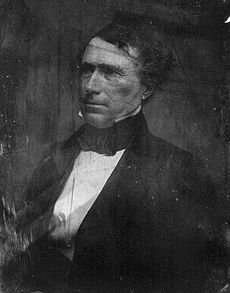

Franklin Pierce (born November 23, 1804 – died October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States. He served as president from 1853 to 1857. He was a Democrat from the Northern states. Pierce believed that the movement to end slavery was a threat to the country's unity. He upset many anti-slavery groups by signing laws like the Kansas–Nebraska Act and enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act. These actions made the conflict between the North and South worse. This conflict eventually led to the American Civil War after Abraham Lincoln became president in 1860.

Pierce was born in New Hampshire. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1833 to 1837. Then he became a Senator from 1837 to 1842. After leaving Congress, he had a successful law practice. He also served as a brigadier general in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War. The Democratic Party chose him as their presidential candidate in 1852. They hoped he could bring together different groups from the North and South. He and his running mate, William R. King, easily won the election against the Whig Party.

As president, Pierce tried to make the government more fair. He also tried to please different parts of the Democratic Party. However, these efforts mostly failed. His popularity in the North dropped sharply after he supported the Kansas–Nebraska Act. This act canceled the Missouri Compromise, which had limited where slavery could spread. The act led to terrible violence in the American West, known as Bleeding Kansas. Pierce's presidency was also hurt by the Ostend Manifesto. This was a plan by some of his diplomats to buy or take Cuba from Spain. Many people criticized this plan. Pierce hoped to be re-nominated for president in 1856, but his party chose someone else. His reputation suffered even more during the Civil War because he often criticized President Lincoln.

Pierce was known for being friendly and outgoing. However, his family life was very sad. All three of his children died young. His wife, Jane Pierce, was often sick and struggled with depression. Their last son died in a train accident just before Pierce became president. Pierce himself died in 1869. Many historians and experts often rank Pierce as one of the least effective U.S. presidents.

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

Childhood and School Days

Franklin Pierce was born on November 23, 1804. He was born in a log cabin in Hillsborough, New Hampshire. His family had lived in America for many generations. His father, Benjamin, was a lieutenant in the American Revolutionary War. After the war, his father bought land in Hillsborough. Franklin was the fifth of eight children. His father was a well-known politician and farmer. Public affairs and the military were important influences in Franklin's early life.

Franklin's father made sure his sons received a good education. Franklin went to school in Hillsborough and then in Hancock. He didn't like school much and once walked 12 miles home because he was homesick. His father made him walk back to school in a thunderstorm. Pierce later said this moment was "the turning-point in my life." He later went to Phillips Exeter Academy to get ready for college. He was known as a charming student, but sometimes got into trouble.

In 1820, Pierce started college at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. He became good friends with Nathaniel Hawthorne, who later became a famous novelist. Pierce struggled with his grades at first. But he worked hard and graduated in fifth place in his class in 1824. During college, he also led a student militia group.

After college, Pierce studied law. He worked with former New Hampshire Governor Levi Woodbury. He also attended Northampton Law School for a semester. In 1827, he became a lawyer in New Hampshire. He lost his first case, but soon became a skilled lawyer. He was good at remembering names and faces, and had a charming personality.

Starting in Politics

By 1824, New Hampshire politics were very divided. Franklin's father, Benjamin Pierce, became governor in 1827. Franklin himself got involved in politics as the 1828 election approached. In 1828, Franklin won his first election. He became the town meeting moderator for Hillsborough. He was re-elected five times.

Pierce actively campaigned for Andrew Jackson, who won the presidency in 1828. In 1829, Franklin won a seat in the New Hampshire House of Representatives. His father was also elected governor again. Franklin became Speaker of the House in 1831. At 27, he was a rising star in the New Hampshire Democratic Party. He worked to protect the state militia and support national Democrats.

Pierce was also part of the state militia. He became an aide to Governor Samuel Dinsmoor in 1831. He stayed in the militia until 1847. He reached the rank of colonel. He worked to improve the state militias. He also became a trustee for Norwich University, a military college.

In late 1832, the Democratic Party nominated Pierce for the U.S. House of Representatives. He was almost guaranteed to win because the Democrats were very strong in New Hampshire. His term began in March 1833. Around this time, he got engaged and bought his first house.

Marriage and Family Life

On November 19, 1834, Pierce married Jane Means Appleton. Jane was the daughter of a minister. Her family supported the Whig Party, which was different from Pierce's Democratic Party. Jane was a quiet and religious person. She was often sick and struggled with depression. She did not like politics, especially living in Washington, D.C. This caused some stress in their marriage as Pierce's political career grew.

Jane also disliked Hillsborough. In 1838, the Pierces moved to Concord, New Hampshire, the state capital. They had three sons, but all of them died young. Franklin Jr. died as a baby in 1836. Frank Robert died at age four in 1843 from a sickness. Their last son, Benjamin, died at age 11 in a train accident in 1853. This happened shortly before Pierce became president.

Serving in Congress

In the U.S. House of Representatives

Pierce went to Washington, D.C., in November 1833. The main goal of the House of Representatives was to prevent the Second Bank of the United States from being rechartered. Pierce and other Democrats succeeded in this. Pierce sometimes disagreed with his party. For example, he opposed using federal money for internal improvements like roads and canals. He believed these were jobs for the states, not the federal government. Pierce was easily re-elected in 1835.

In the 1830s, the movement to end slavery grew stronger. Congress received many petitions from anti-slavery groups. Pierce found these "agitations" annoying. He saw federal action against slavery as interfering with the rights of Southern states. He was personally against slavery but believed it was a "social and political evil" that should be handled by states. He worried that the abolitionist movement would break up the country.

Pierce supported the "gag rule" in the House. This rule allowed anti-slavery petitions to be received but not discussed. This meant they were basically ignored. Some newspapers criticized Pierce for this, calling him a "doughface" – a Northerner who sided with the South.

In the U.S. Senate

In December 1836, Pierce was elected to the Senate. He was 32 years old, making him one of the youngest senators ever. This was a difficult time for Pierce. His father, sister, and brother were all very sick. His wife also continued to have poor health. As a senator, Pierce helped his friend Nathaniel Hawthorne get a job.

Pierce usually voted with his party. He was a capable senator but not one of the most famous. He was overshadowed by powerful senators like John C. Calhoun, Henry Clay, and Daniel Webster. Pierce entered the Senate during an economic crisis called the Panic of 1837. He believed the crisis was caused by too much banking and speculation. He supported President Martin Van Buren's plan for an Independent Treasury. This plan would keep federal money separate from private banks.

Debates about slavery continued in Congress. Abolitionists wanted to end slavery in Washington, D.C. Pierce supported a resolution against this idea. He saw it as a dangerous step towards ending slavery everywhere. The Whig Party was also growing stronger in Congress.

Pierce was very interested in the military. He wanted to modernize and expand the Army. He focused on improving state militias and making the Army more mobile. He became chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Pensions.

In December 1841, Pierce decided to resign from Congress. New Hampshire Democrats usually limited senators to one six-year term. Also, he was frustrated being in the minority party. He wanted to spend more time with his family and his law practice. He left the Senate in February 1842.

Becoming a Party Leader

Lawyer and State Politics

Even after leaving the Senate, Pierce stayed involved in public life. Moving to Concord gave him more opportunities for legal cases. His wife, Jane, also enjoyed the community life there. Pierce became a very successful lawyer. He was known for his friendly personality, good speaking skills, and excellent memory. He often helped poor people without charging much.

Pierce remained active in the New Hampshire Democratic Party. He became chairman of the State Democratic Committee in 1842. He helped the more radical part of the party gain control of the state legislature. Pierce valued party unity very highly. He believed that opposition to slavery threatened this unity.

In 1844, James K. Polk won the presidential election. Pierce had campaigned strongly for Polk. In return, Polk appointed Pierce as the U.S. Attorney for New Hampshire. Polk wanted to annex Texas, which caused a big disagreement between Pierce and his friend, John P. Hale. Hale was against adding a new slave state. Pierce helped remove Hale's nomination for Congress. This led to a major political fight and split the Democratic Party in New Hampshire.

Military Service in the Mexican–American War

Pierce had always wanted to serve in the military. He admired his father's and brothers' service. When the U.S. declared war on Mexico in May 1846, Pierce immediately volunteered. He turned down an offer to become Polk's Attorney General because he wanted to fight. In February 1847, he was appointed colonel of the 9th Infantry Regiment.

On March 3, 1847, Pierce was promoted to brigadier general. He took command of a brigade of soldiers. He arrived in Mexico in late June and led 2,500 men with supplies to join General Winfield Scott's army. This three-week journey was dangerous, with several attacks.

During the Battle of Contreras, Pierce's horse was startled and fell, pinning him underneath. He injured his knee. He returned for the next day's battle, but re-injured his knee and passed out from the pain. Despite this, he continued to lead his brigade. He took part in the capture of Mexico City in September.

Pierce returned to New Hampshire in December 1847. He was welcomed as a hero. He resigned from the Army in March 1848. His military service made him more popular. However, his injuries and struggles in battle led to some people accusing him of cowardice.

Ulysses S. Grant, who saw Pierce during the war, later defended him. Grant wrote that Pierce was "a gentleman and a man of courage."

Back in New Hampshire

After the war, Pierce went back to his law practice in Concord. The U.S. gained a lot of land from Mexico, which was called the Mexican Cession. This new land caused a big political debate about whether slavery should be allowed there. Many Northerners wanted to stop slavery from spreading. Southerners felt it should be allowed in territories gained with their help. This disagreement split the Democratic Party.

In 1850, Senator Henry Clay proposed a set of laws called the Compromise of 1850. These laws aimed to settle the slavery question by giving something to both the North and the South. Pierce strongly supported this compromise. He gave a speech in December 1850, saying he was committed to "The Union! Eternal Union!" He believed the compromise was important to keep the country together.

The 1852 Presidential Election

As the 1852 election neared, the Democrats were still divided over slavery. Many expected the 1852 Democratic National Convention to be stuck, with no main candidate getting enough votes. Pierce's supporters in New Hampshire saw an opportunity for him to be a "dark horse" candidate, meaning someone not expected to win. Pierce publicly said he didn't want the nomination, but he quietly allowed his supporters to work for him. He made sure to state his support for the Compromise of 1850, including the controversial Fugitive Slave Act.

The convention met in Baltimore in June. As expected, no candidate could win. After many votes, Pierce started to gain support. On the 49th vote, he received almost all the votes and became the Democratic nominee for president. The delegates chose Senator William R. King as his running mate. The party platform said they would not argue about slavery anymore and supported the Compromise of 1850.

When Pierce heard the news, he found it hard to believe. His wife fainted. Their son Benjamin wrote to his mother, hoping his father wouldn't win, because he knew she wouldn't like living in Washington.

The Whig Party chose General Scott, Pierce's former commander, as their candidate. The Whigs were also divided and their platform was very similar to the Democrats'. This made the election mostly about the candidates' personalities. Pierce stayed quiet during the campaign, as was the custom for candidates then. His opponents tried to make him look like a coward. Scott struggled to get support from his own party.

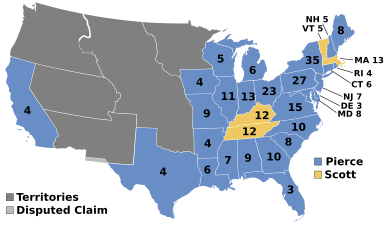

Pierce won the election easily. He received 254 electoral votes compared to Scott's 42. He also won the popular vote with 50.9 percent. The Democrats also won large majorities in Congress.

Presidential Term (1853–1857)

A Sad Start to the Presidency

Pierce's presidency began with great sadness. Just weeks after he was elected, on January 6, 1853, Pierce and his family were in a train accident. Their car went off the tracks near Andover, Massachusetts. Franklin and Jane Pierce survived, but their only remaining son, 11-year-old Benjamin, died. Both parents suffered from severe depression after this tragedy. This likely affected Pierce's work as president. Jane Pierce wondered if the accident was a punishment from God for her husband becoming president. She avoided social events for most of her first two years as First Lady.

When Franklin Pierce left New Hampshire for his inauguration, Jane Pierce did not go with him. Pierce was the youngest man elected president at that time. He chose to affirm his oath on a law book instead of a Bible. He was the first president to give his inaugural speech from memory. In his speech, he talked about peace and prosperity at home. He also spoke about expanding U.S. territory. He avoided using the word "slavery" but said he wanted to settle the "important subject" and keep the country peaceful. He also mentioned his personal tragedy, asking the crowd to support him in his weakness.

Cabinet and Government Changes

| The Pierce Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Franklin Pierce | 1853–1857 |

| Vice President | William R. King | 1853 |

| None | 1853–1857 | |

| Secretary of State | William L. Marcy | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of Treasury | James Guthrie | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of War | Jefferson Davis | 1853–1857 |

| Attorney General | Caleb Cushing | 1853–1857 |

| Postmaster General | James Campbell | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of the Navy | James C. Dobbin | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Robert McClelland | 1853–1857 |

Pierce tried to unite his party by giving different groups some positions in his Cabinet. All of his cabinet choices were quickly approved by the Senate. Pierce spent weeks filling hundreds of lower-level government jobs. This was difficult because he tried to please all parts of the party, but ended up satisfying no one completely. Soon, Northern newspapers accused him of favoring pro-slavery people. Southern newspapers accused him of supporting abolitionists.

Disagreements grew quickly within the Democratic Party. Vice President-elect William R. King was very sick with tuberculosis. He went to Cuba to recover and was sworn in there. He died on April 18, 1853, just over a month into his term. The office of vice president remained empty for the rest of Pierce's presidency.

Pierce wanted a more efficient government. His cabinet members started an early system of civil service exams. This was a step towards hiring people based on skill, not political connections. The Interior Department was reorganized to be more efficient. Pierce also expanded the role of the U.S. attorney general in appointing federal judges. This helped create the Justice Department. Pierce appointed only one Supreme Court Justice, John Archibald Campbell.

Economy and Infrastructure

Pierce asked Treasury Secretary James Guthrie to improve the Treasury. Guthrie increased oversight of employees and tax collectors. He also brought federal money back from private banks into the Treasury.

Secretary of War Jefferson Davis led surveys for possible transcontinental railroad routes. This was a big project to connect the country by rail. Davis also used the Army Corps of Engineers for construction projects in Washington, D.C. This included expanding the United States Capitol building.

Foreign Relations and Expansion

The Pierce administration supported the Young America movement, which wanted the U.S. to expand its influence. Secretary of State William L. Marcy wanted American diplomats to wear "the simple dress of an American citizen" instead of fancy European uniforms. He also said they should only hire American citizens.

Davis, the Secretary of War, wanted a southern route for a transcontinental railroad. He convinced Pierce to send James Gadsden to Mexico to buy land. Gadsden negotiated the Gadsden Purchase in December 1853. This purchase added a large area of land to the American Southwest. It brought the contiguous United States to its current borders.

Pierce's administration also worked to improve relations with Great Britain. Marcy completed a trade agreement with Britain. This agreement helped reduce conflicts over fishing rights near Canada. Pierce saw this as a step towards the U.S. possibly annexing Canada.

Pierce's administration also caused controversy with the Ostend Manifesto. Three U.S. diplomats in Europe wrote a proposal to buy Cuba from Spain. They even suggested taking it by force if Spain refused. When this plan became public, Northerners were angry. They saw it as an attempt to add another slave state to help Southern interests. This document hurt the idea of Manifest Destiny, which was the belief that the U.S. was meant to expand across North America.

Under Pierce, Commodore Matthew C. Perry visited Japan. This trip, planned earlier, aimed to open trade with Japan. Perry signed a trade treaty with the Japanese government, which was approved.

The "Bleeding Kansas" Conflict

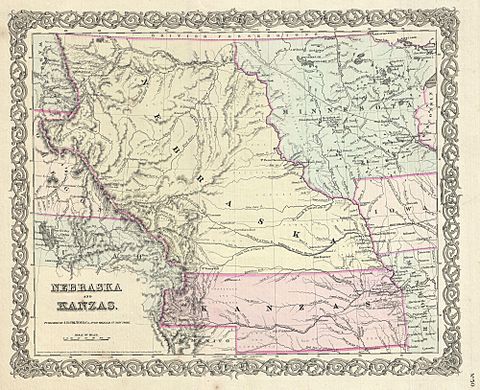

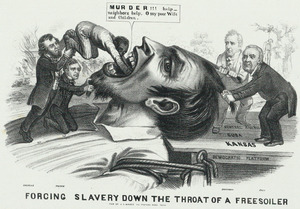

The biggest challenge during Pierce's presidency was the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Senator Stephen A. Douglas wanted to organize the large, unsettled Nebraska Territory for western expansion. He wanted a transcontinental railroad to go through it. To get Southern support, Douglas proposed letting settlers in the new territories decide for themselves whether to allow slavery. This idea was called popular sovereignty. This would cancel the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had banned slavery north of a certain line. The territory would be split into Nebraska (North) and Kansas (South). The expectation was that Kansas would allow slavery.

Pierce was unsure about the bill, knowing it would cause strong opposition in the North. But Douglas and Secretary of War Davis convinced him to support it. Northerners strongly opposed the bill. They saw it as part of a plan to expand slavery. The act caused a huge political uproar and greatly damaged Pierce's presidency.

The Kansas–Nebraska Act passed in May 1854. It led to so much violence between pro-slavery and anti-slavery groups that the territory became known as Bleeding Kansas. Thousands of pro-slavery people from Missouri, called Border Ruffians, illegally voted in Kansas elections. This gave the pro-slavery side the victory. Pierce supported this outcome, even with the problems. When anti-slavery settlers formed their own government, Pierce called it a rebellion. He sent federal troops to break up their meetings.

At the same time, an escaped slave named Anthony Burns was captured in Boston. Northerners protested, but Pierce was determined to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. He sent federal troops to return Burns to his owner in Virginia, despite angry crowds.

The elections of 1854 and 1855 were disastrous for the Democrats. They lost many states outside the South. A new anti-immigrant party, the Know Nothings, gained power. The Republican Party was also founded around this time. In Pierce's home state of New Hampshire, the Know-Nothings won many elections.

The 1856 Election

Pierce expected to be nominated again by the Democrats. However, his chances were slim because he was so unpopular in the North due to the Kansas–Nebraska Act. When the Democratic convention met in June 1856, Pierce did not get enough votes to win. After many votes, Pierce told his supporters to vote for Stephen A. Douglas. But Douglas also withdrew his name. Finally, James Buchanan became the clear winner. This was the only time an elected president seeking re-election was not nominated by his party.

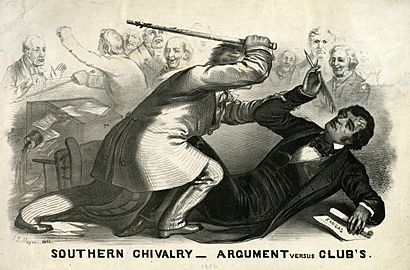

Pierce supported Buchanan, even though they were not close. He hoped to fix the Kansas situation before the general election. He appointed John W. Geary as governor of Kansas. Geary helped restore order, but the political damage was already done. Republicans used "Bleeding Kansas" and "Bleeding Sumner" (referring to a violent attack on Senator Charles Sumner in Congress) as campaign slogans.

Buchanan won the election, but the Democratic Party lost a lot of support in the North. Pierce did not change his strong opinions after losing the nomination. In his final message to Congress, he strongly criticized Republicans and abolitionists. He also defended his economic policies and foreign relations. Pierce and his cabinet left office on March 4, 1857. This was the only time in U.S. history that all original cabinet members stayed for a full four-year term.

Life After the Presidency (1857–1869)

After leaving the White House, the Pierces traveled for three years. They visited Madeira, Europe, and the Bahamas. In Rome, he visited his friend Nathaniel Hawthorne. Pierce continued to follow politics. He believed Northern abolitionists should stop their actions to prevent the Southern states from leaving the Union. He warned that a civil war would cause bloodshed everywhere. He also criticized New England ministers who supported abolition.

As the 1860 Democratic Convention approached, some people asked Pierce to run again. They hoped he could unite the divided party. But Pierce refused. The split Democrats lost the presidency to the Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln. After Lincoln's election, several Southern states began to plan to secede. Pierce tried to appeal to the people of Alabama to stay in the Union.

During the Civil War

When the American Civil War began, Pierce wanted to avoid war at all costs. He suggested that former U.S. presidents meet to solve the problem, but this didn't happen. Pierce openly opposed President Lincoln's order to suspend habeas corpus. This meant people could be arrested without being told why. Pierce argued that even during war, civil liberties should be protected. This view made him popular with some Northern Democrats who wanted peace. However, others saw it as a sign that Pierce favored the South.

In September 1861, Pierce was falsely accused of meeting with disloyal people and plotting against the government. A newspaper called him a "prowling traitor spy." Pierce denied these charges. He later made his letters with Secretary of State William H. Seward public to clear his name.

Pierce was also angered by the draft and the arrest of a Democrat who criticized Lincoln. In July 1863, he gave a speech criticizing Lincoln. He asked, "Who... has clothed the President with power to dictate to any one of us when we must or when we may speak...?" These comments were not well received in the North, especially after the Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. Pierce's reputation was further damaged when his pre-war letters with Confederate president Jefferson Davis were published. These letters showed their friendship and Pierce's predictions of civil war.

Jane Pierce died in December 1863. Pierce was also saddened by the death of his close friend Nathaniel Hawthorne in May 1864. Some Democrats tried to consider Pierce for the 1864 election, but he stayed away. Lincoln easily won a second term. After Lincoln's assassination in April 1865, a crowd gathered outside Pierce's home. They wanted to know why he hadn't raised a flag to mourn Lincoln. Pierce was angry but expressed sadness. He told them his military and public service proved his patriotism.

Later Years and Death

Pierce's health declined in his later years. He became more spiritual. He used his influence to help improve the treatment of Jefferson Davis, who was a prisoner. He also offered financial help to Hawthorne's son and his own nephews. He spent most of his time in Concord and at his cottage by the coast.

Pierce died on October 8, 1869, at age 64. President Ulysses S. Grant declared a day of national mourning. Newspapers across the country wrote about Pierce's life. Pierce was buried next to his wife and two sons in Concord's Old North Cemetery.

In his will, Pierce left many personal items to friends and family. Much of his money went to his brother's family and Hawthorne's children.

Places and Honors Named After Pierce

Pierce received honorary degrees from Bowdoin College and Dartmouth College.

Several places in New Hampshire are connected to Pierce:

- The Franklin Pierce Homestead in Hillsborough is a state park and a National Historic Landmark. You can visit it.

- The Franklin Pierce House in Concord, where he died, burned down in 1981.

- The Pierce Manse, his home in Concord from 1842 to 1848, is also open to visitors.

Other places named after him include:

- Franklin Pierce University in Rindge, New Hampshire.

- The University of New Hampshire School of Law was once called the Franklin Pierce Law Center.

- Mt. Pierce in New Hampshire's White Mountains.

- The town of Pierceton, Indiana.

- Pierce County, Washington.

- Pierce County, Georgia.

Pierce's Legacy

After his death, Franklin Pierce was mostly forgotten by the public. He is often seen as one of the least successful presidents in American history. His presidency is widely considered a failure. One reason was that he allowed a divided Congress to take the lead, especially with the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Although Senator Douglas led that effort, Pierce's reputation suffered greatly. His failure to bring the country together helped end the Democratic Party's power. This led to over seventy years where Republicans mostly controlled national politics.

Historian Eric Foner said, "His administration turned out to be one of the most disastrous in American history."

Pierce was known as a good politician and a likable person. However, during his presidency, he mostly tried to be a mediator between the angry groups that were pushing the nation towards civil war. Pierce believed the Union was sacred. He saw the actions of abolitionists as a threat to the rights of Southerners. While he criticized those who wanted to limit slavery, he rarely spoke out against Southern politicians who took extreme views.

Historians often point to the Ostend Manifesto and the Kansas–Nebraska Act as the two biggest problems of his time in office. These events brought a lot of public criticism. They also made the ideas of Manifest Destiny and "popular sovereignty" less popular. Some historians, however, view Pierce's foreign policy more positively. They say his ideas about expansion were similar to later presidents like William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Franklin Pierce para niños

In Spanish: Franklin Pierce para niños

- New Hampshire Historical Marker No. 80: Franklin Pierce 1804–1869

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |