Anthony Burns facts for kids

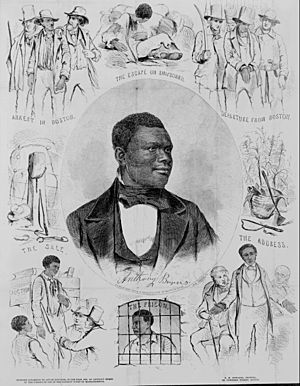

Anthony Burns (born May 31, 1834 – died July 17, 1862) was an African American man who bravely escaped slavery in Virginia in 1854. His capture and trial in Boston, Massachusetts, and his forced return to Virginia, caused huge anger in the Northern states. This event made many more Northerners strongly oppose slavery.

Anthony was born into slavery in Stafford County, Virginia. As a young man, he became a Baptist and a "slave preacher." He often worked for different people, which helped him learn to read and write. In 1853, he escaped slavery and reached Boston, Massachusetts, a free state, where he found work.

The next year, he was caught under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This law was hated in Boston. Anthony's case became famous across the country, leading to big protests and even violence. The government even used federal troops to make sure Anthony was sent back to Virginia without trouble.

Later, friends in Boston bought Anthony's freedom from slavery. After that, he studied at Oberlin Collegiate Institute. He became a Baptist preacher again. He was asked to work in Upper Canada (now Ontario). About 30,000 African Americans, both enslaved and free, had moved there to find freedom. Anthony lived and worked there until he died.

Contents

Anthony Burns' Early Life as an Enslaved Person

Anthony Burns was born into slavery in Stafford County, Virginia, on May 31, 1834. His mother was enslaved by John Suttle. Anthony was her youngest of 13 children. His father was believed to be a free man.

After John Suttle died, his wife took over. She sold some of Anthony's older siblings to avoid losing everything. Eventually, Anthony's mother was also sold. Anthony did not see her for two years. When Anthony was six, Mrs. Suttle died. Her oldest son, Charles F. Suttle, inherited Anthony.

To pay off family debts, Charles Suttle used his enslaved people as a guarantee for loans. Anthony began his first tasks as an enslaved child. He looked after his niece so his sister could work. He also stayed at the House of Horton, where his sister lived. There, children taught Anthony the alphabet in exchange for small favors.

At age seven, Anthony was hired out to three women for $15 a year. He ran errands and collected cornmeal. This was his first experience with religion. At age eight, he worked for $25 a year. Children there taught him to spell using their school worksheets. Anthony entertained them in return. He left this job after two years due to poor treatment.

Anthony was then leased to William Brent. Brent's wife was kind to Anthony. He stayed there for two years, earning Suttle $100. Under Brent, Anthony learned about a free land in the North. He began to dream of escaping. Anthony did not want to work for Brent a third year. Suttle let him find new work, knowing a willing worker was better.

Anthony found a new master through a lease. Suttle agreed to let Anthony work for Foote in his saw-mill for $75 a year. Anthony was 12 or 13 years old. He continued his education with Foote’s daughter. However, Foote and his wife were very cruel. They beat even their youngest enslaved people. After a few months, Anthony hurt his hand badly in a machine. He was sent back to Suttle to recover.

While recovering, Anthony had a strong religious experience. He became very interested in the religious excitement spreading in his county. Suttle first refused his request to be baptized. But later, Suttle gave Anthony permission. Suttle took Anthony to the Baptist Church in Falmouth. Free white people and enslaved black people were separated by a wall during services.

Two years later, Anthony was chosen to preach to church members. He became a preacher at this church. Anthony preached mainly to groups of enslaved people. This was risky because Virginia law required white ministers to supervise all-black church meetings. Anthony said that if officers found them, enslaved people who didn't escape would be caged and whipped. As a preacher, Anthony also performed marriages and funerals for enslaved people.

After his hand healed, Anthony returned to Foote's service. He finished his year and was hired by a new master in Falmouth, Virginia, where his church was. His new master loaned him to a merchant for six months. Anthony was treated badly by this merchant. He refused to stay with him after his year was done.

For the next year, Anthony worked in Fredericksburg, Virginia, for a tavern-keeper. He earned $100 for his master. A year later, Anthony worked in a pharmacy in the same city. He met a fortune teller who promised him freedom soon.

Later, Suttle hired William Brent (Anthony’s former master) to manage his enslaved people. Brent moved Anthony to Richmond, Virginia. Anthony was excited to be in a city with ships sailing North. In Richmond, Brent hired Anthony out to his brother-in-law. Anthony did not get along with him. By this time, Anthony was good at reading and writing. He secretly taught other enslaved people how to read and write.

After his time with Brent’s brother-in-law, Anthony worked for a man named Millspaugh. Millspaugh realized he didn't have enough work for Anthony. So, he sent Anthony to find small jobs and earn money for him. At first, they met daily, but then changed to every two weeks. Anthony was encouraged to escape by sailors and free men he worked with. He felt a religious duty to his owner, but found a way to justify leaving. One day, Anthony gave Millspaugh $25. After seeing such a large sum, Millspaugh demanded daily visits. Anthony refused and left without permission. This made his escape urgent. Anthony planned with a sailor friend. One morning in early February 1854, Anthony boarded a ship heading North.

Anthony Burns' Escape and Capture

We went to bed one night old-fashioned, conservative, compromise Union Whigs & waked up stark mad Abolitionists.

Anthony Burns left Richmond, Virginia, in early February 1854. His friend hid him in a small space on the ship. Anthony slept after many anxious nights. When he woke, the ship was far from the harbor. It was on its way to Norfolk, Virginia, then to Boston, Massachusetts. Anthony was stuck in the same spot for over three weeks. He suffered from thirst, hunger, and severe seasickness. His friend brought him food and water every few days, just enough to survive.

The ship reached Boston in late February or early March. Anthony immediately looked for work. First, he worked as a cook on a ship but was fired after a week. Then, Anthony found a job with Collin Pitts, a black man, at a clothing store on Brattle Street. He enjoyed only one month of freedom before being arrested.

While in Boston, Anthony sent a letter to his enslaved brother in Richmond. He told him about his new home. His brother’s owner found the letter and told Suttle about Anthony’s escape. Suttle went to a courthouse in Alexandria County. The judge ruled that Suttle had enough proof he owned Burns. A warrant was issued for Anthony’s arrest under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

The warrant was issued on May 24, 1854. It ordered Watson Freeman, the United States Marshal of Massachusetts, to arrest Anthony Burns. He was to bring him before Judge Edward G. Loring for trial. On the same day, Deputy Marshal Asa O. Butman, a known slave hunter, was given the job to arrest Anthony.

On May 24, 1854, Butman watched Burns at the clothing store before arresting him. He wanted to make a peaceful arrest to avoid a crowd trying to rescue Burns. After Burns and Pitts closed their store, they walked home separately. Butman stopped Burns at the corner of Court and Hanover streets. He arrested him, pretending it was for a jewelry store robbery. Burns, knowing he was innocent, went with Butman to the courthouse. There, Burns expected to see the jewelry store owner. Instead, he met U.S. Marshal Freeman. At that moment, Burns knew he had been caught under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

Anthony Burns' Trial in Boston

At the start of the trial, prosecutors tried to keep it secret. However, Richard Henry Dana Jr. heard about it and offered to help Burns. Burns first refused, thinking it was useless, but then agreed.

In the first hearing, Charles Suttle (the owner) had William Brent testify to confirm Burns’ identity. Dana, Burns’ lawyer, stopped Brent from talking about a conversation he had with Burns and Suttle the night of the arrest. The judge agreed to delay the trial until May 27, then again until May 29. Theodore Parker, a witness, said Burns was hesitant to accept a lawyer because he feared how much Brent and Suttle knew about him.

During the trial, Burns was held in a jury room. Armed guards watched him constantly. They tried to trick him into admitting he was a slave, but Burns avoided their traps. Suttle, angry that the public saw him as a cruel master, asked Anthony to write a letter proving otherwise. But Leonard Grimes, a Boston clergyman and abolitionist, told Burns to destroy the letter.

The final hearing began on May 29, 1854. Armed soldiers guarded the courthouse windows. They stopped officials and citizens from entering. Even Dana, Burns’ main lawyer, couldn’t get in until later. Charles Ellis, Burns’ other lawyer, argued that the trial shouldn't continue while Suttle’s lawyer carried guns, but the judge disagreed. The judge allowed Suttle to use the conversation between Suttle and Burns from the night of the arrest as evidence. They also showed a book with the Virginia court’s ruling in Suttle’s favor.

Burns’ lawyers argued that Suttle’s timeline was wrong. They said Suttle didn't have enough proof that Burns was the runaway slave. They brought in William Jones, a black man, who said he met Anthony in Boston on March 1. They also called seven other witnesses to support his story. James Whittemore, a Boston city council member, testified that he saw Burns in Boston around March 8. He identified Burns by his scars.

In his final decision, Judge Loring said he disliked the Fugitive Slave Act. However, he said his job was to follow the law. Loring stated that Suttle had enough evidence to prove the runaway slave matched Anthony’s appearance. So, he ruled in favor of Suttle.

It is estimated that the government spent over $40,000 (about $1.5 million today) to capture and try Burns.

Riot at the Courthouse

Many citizens were interested in Burns’ trial, especially the Committee of Vigilance. This group was formed after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Their goal was to stop the law from being used for people like Burns. The committee included people from all walks of life and races. They discussed two plans: attacking the courthouse to free Anthony, or forming a large crowd to block his removal. They chose the more peaceful plan of creating a crowd. They also placed men at the courthouse to watch for any attempts to move Burns secretly.

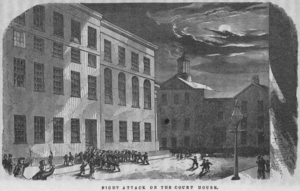

Even though the committee chose a peaceful plan, some men decided to rescue Burns themselves. On Friday evening, May 26, the committee left their meeting at Faneuil Hall around 9 p.m. At that time, at least 25 men, armed with revolvers and axes, gathered. More people joined them on the way to the courthouse. They attacked by breaking down the doors with axes and wooden beams. A fight broke out between guards and rioters. One guard, James Batchelder, was killed.

The riot did not last long after police arrived. Many abolitionists were arrested. It is unlikely the attack would have freed Anthony, as he was held in a very secure room on the top floor.

A grand jury charged three people involved in the attack. One man was found not guilty. For others, juries could not agree. So, the federal government dropped the charges.

After the riot, President Franklin Pierce sent the United States Marines to Boston. They helped the police prevent more violence. The city of Boston was very tense, waiting for the next part of the trial. When Loring ruled in Suttle’s favor, abolitionists began preparing for Burns’ transfer.

Aftermath of the Trial

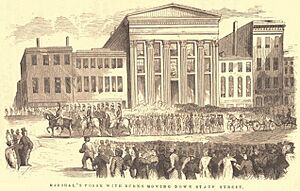

After the trial, Marshal Freeman had to move Burns from the courthouse without trouble from the Boston crowd. Jerome V. C. Smith, the mayor of Boston, was in charge of keeping the peace. Citizens tried to convince the mayor to help free Burns. At first, they convinced him to use only one military company to guard the courthouse on the day Burns was moved. Like Loring, Mayor Smith disliked the Fugitive Slave Act. However, Marshal Freeman felt one company was not enough. He pushed the mayor to call in more troops. Mayor Smith ended up using an entire brigade of state militia to clear the streets for Burns’ transfer.

While the mayor planned for crowd control, Freeman gathered 125 Boston citizens to help move Burns. The Marshal swore these men in and armed them with pistols and cutlasses. From the day Loring made his decision until June 2, Burns stayed in the same jury room. During this time, Burns’ friends tried to buy his freedom. But Suttle refused to negotiate as long as Burns was in his service.

At 2 p.m. on June 2, 1854, Burns was escorted from the courthouse. Marshal Freeman and his men, along with 140 U.S. Marines and soldiers, led the way. State militia brigades lined the streets to control the crowd. Along their route, citizens showed symbols of Burns’ lost freedom. One man hung a black coffin. Others draped their windows in black. At one point, the guards turned into a street full of spectators. Officers charged them with bayonets. One man, William Ela, was beaten and arrested. Finally, the officers and Burns reached the wharf. The ship to Virginia was waiting there. At 3:20 p.m., Suttle, Brent, and Burns left Boston for Virginia.

Because of Burns’ trial, Massachusetts passed a strong liberty law. This law said slave claimants could not be on state property. It also required fugitive slaves to have a trial by jury. Slave claimants had to bring two reliable witnesses. Burns’ trial was the last time a fugitive slave was returned from Massachusetts. Judge Loring faced serious consequences. Harvard University refused to re-hire him. The Massachusetts legislature voted to remove him from his state judge position. The governor at the time did not approve it. However, in 1857, a new governor signed Loring’s removal. This angered politicians in Washington, D.C.. President James Buchanan then appointed Loring to a federal court position.

Freedom and Later Life

After leaving Massachusetts, Burns spent four months in a Richmond jail. He was kept separate from other enslaved people. In November, Suttle sold Burns to David McDaniel for $905. McDaniel took Burns to his plantation in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. McDaniel was a strict businessman who often bought and sold enslaved people. He had between 75 and 150 enslaved people on his plantation. Burns worked as McDaniel’s coachman and stable-keeper. This was a lighter workload than other enslaved people had. Instead of staying with other enslaved people, Burns had an office and ate meals in his master’s house. Because of this good treatment, Burns promised not to run away from McDaniel.

Burns also attended church twice while with McDaniel. He even held secret religious meetings for other enslaved people. McDaniel found out but did not punish Burns as he would others. The overseer on the plantation disliked Burns getting special treatment. He once threatened Burns with a pistol. Burns only reported to McDaniel. During these months, Burns did not tell his Northern friends where he was.

One afternoon, Burns drove his mistress to a neighbor’s house. A neighbor recognized Burns as the slave from the Boston trial. A young lady overheard this story. She wrote about it to her sister in Massachusetts. Her sister told her friends, including Reverend Stockwell. Stockwell then told Leonard Grimes. Grimes was a known abolitionist who helped runaway slaves. He had even built the Church of Fugitive Slaves in Boston.

Stockwell wrote to McDaniel to buy Burns’ freedom. McDaniel replied he would sell Burns for $1300. In two weeks, Grimes collected enough money. Stockwell paid for their trip to Baltimore to meet McDaniel and Burns. Grimes went alone after Stockwell couldn't make it.

McDaniel knew selling Burns to Northerners was unpopular in North Carolina. So, he made Anthony promise to keep it a secret. On their train to Norfolk, someone spread a rumor that the famous runaway slave from Boston was on board. Many passengers and even the conductor were angry. The conductor said he would not have let Burns on if he had known. McDaniel stood firm and kept the crowd away. When they arrived in Norfolk, Burns boarded their ship to Baltimore before McDaniel. There, another curious crowd gathered. When McDaniel arrived, their anger turned to him. Some men tried to buy Burns for more money than Grimes was paying. McDaniel refused but agreed to sell Burns if Grimes didn't show up.

In Baltimore, Burns and McDaniel met Grimes at Barnum’s Hotel. They arrived two hours after Grimes. Negotiations began right away. The payment was delayed because McDaniel wanted cash instead of Grimes’ check. Eventually, the cash was exchanged, and Anthony’s freedom was bought. As they left the hotel, Grimes and Burns met Stockwell. He went with them to the train station. Burns spent his first night as a free man in Philadelphia.

Anthony Burns reached Boston in early March. He was met with a public celebration of his freedom. Eventually, Burns enrolled at Oberlin College with a scholarship. He then went to a seminary in Cincinnati to continue his religious studies.

After preaching briefly in Indianapolis, Burns moved to St. Catharine's, Ontario, Canada, in 1860. He accepted a position at Zion Baptist Church. Thousands of African Americans had moved to Canada as refugees from slavery before the Civil War, creating communities in Ontario.

Anthony Burns died from tuberculosis on July 17, 1862.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |