Plantation complexes in the Southern United States facts for kids

A plantation complex in the Southern United States was a large farm with many buildings, common in the American South from the 1600s to the 1900s. These complexes included everything from the main house where the owner lived to the animal pens. Southern plantations were usually like small towns, producing most of what they needed. They relied on the forced work of enslaved people.

Plantations are a very important part of the history of the Southern United States, especially the time before the American Civil War (called the Antebellum era). The warm weather, lots of rain, and rich soil in the southeastern United States helped large plantations grow. On these plantations, many African Americans were held captive and forced to grow crops. This work created a lot of wealth for the white owners.

Today, people have different ideas about what made a plantation different from a regular farm. Farms usually grew food just for the family. Plantations, however, mainly grew "cash crops" like cotton or tobacco to sell. They also grew enough food to feed the people and animals on the estate. A common idea is that a plantation had 500 to 1000 acres (about 2 to 4 square kilometers) or more land and grew one or two main crops for sale. Some experts also define plantations by the number of enslaved people who worked there.

Contents

What was a Plantation Complex?

Most plantations were not huge estates with grand mansions. While these large places did exist, they were only a small part of all the plantations in the South. Many Southern farmers held enslaved people before they were freed in 1862, but most owned fewer than five. These farmers often worked in the fields alongside the people they enslaved. In 1860, there were about 46,200 plantations. About 20,700 of them had 20 to 30 enslaved people, and 2,300 had 100 or more. The rest were somewhere in between.

Many plantations were run by owners who didn't live there and never had a main house on the property. Other buildings were just as important, or even more so. These included structures for processing and storing crops, preparing and storing food, sheltering tools and animals, and other daily tasks. The value of a plantation came from its land and the enslaved people who worked hard to produce crops for sale. These same people also built the homes for the owners, the cabins for enslaved people, barns, and all the other buildings.

Most building materials for a plantation came from the land itself. Wood was cut from the forests on the property. Depending on what it was used for, it was split, shaped, or sawn. Bricks were usually made on-site from sand and clay. The clay was shaped, dried, and then baked in a special oven called a kiln. If good stone was available, it was used. A material called tabby (made from oyster shells, sand, and lime) was often used on the southern Sea Islands.

Few plantation buildings have survived to today. Most were destroyed over time by natural disasters, neglect, or fire. When the plantation economy ended and the South changed from farming to industry, plantations and their buildings became less important. Even though most are gone, the main plantation houses are the most common buildings that still exist. Stronger, more interesting buildings tended to last longer and are better recorded than smaller, simpler ones. Several homes of important people, like Mount Vernon, Monticello, and The Hermitage, have been saved. Intact examples of slave housing are less common. The rarest survivors are the farm buildings and smaller household structures from before the Civil War.

Slave Quarters: Homes for Enslaved People

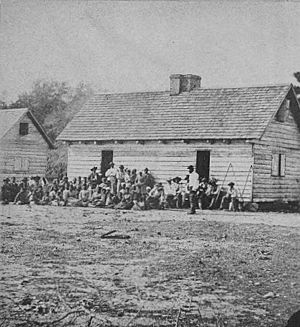

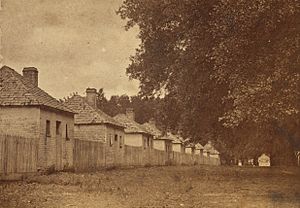

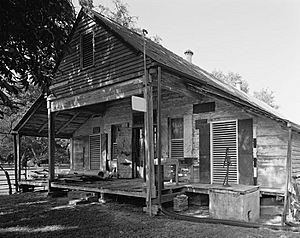

Homes for enslaved people were once very common on plantations, but most have disappeared. Many were not built to last. Only the stronger ones survived, usually if they were used for other purposes after slavery ended. Slave quarters could be close to the main house, far away, or both. On large plantations, they were often grouped like a small village along a road away from the main house. Sometimes, they were spread out around the plantation near the fields where the enslaved people worked.

Slave houses were often very simple. They were mostly for sleeping and were usually rough cabins made of logs or wood frames, with one room. Early ones often had chimneys made of clay and sticks. Some had two rooms, offering a separate space for eating and sleeping. Sometimes, dormitories or two-story buildings were also used. Most of these were for enslaved people who worked in the fields. Rarely, like at the former Hermitage Plantation in Georgia or Boone Hall in South Carolina, even field workers had brick cabins.

Enslaved people who worked in the main house or had special skills often had better living spaces. They usually lived in a part of the main house or in their own homes, which were more comfortable than those for field workers. A few owners went even further. When Waldwic in Alabama was updated in 1852, the house servants were given large homes that matched the main house's style. However, this was very unusual.

The famous landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted visited plantations along the Georgia coast in 1855. He wrote about seeing "little villages of slave-cabins" about a quarter of a mile from the main road. He described them as "framed buildings, boarded on the outside, with shingle roofs and brick chimneys." They were "fifty feet apart, with gardens and pig-yards." At the end of the village, there was an overseer's house.

Other Homes on the Plantation

On larger plantations, an important building was the overseer's house. The overseer was in charge of making sure the plantation ran smoothly and that crop goals were met. They also oversaw the health of the enslaved people and inspected their homes. The overseer kept records of crops and held keys to storage buildings.

The overseer's house was usually a simple home, not far from the cabins of the enslaved workers. Overseers and their families, even if they were white, did not socialize with the plantation owner's family. They were in a different social class. In slave villages, the overseer's house was usually at the head of the village, not near the main house. This was partly due to their social position and also to help keep the enslaved people under control.

Studies show that fewer than 30 percent of plantation owners hired white overseers. Some owners chose a trusted enslaved person to be the overseer. In Louisiana, free Black overseers were also sometimes used.

Another type of home found mostly on plantations was the garçonnière, or bachelors' quarters. These were built mainly by Louisiana Creole people, but sometimes in other parts of the Deep South that were once part of New France. They were buildings that housed the teenage or unmarried sons of plantation owners. At some plantations, it was a separate building, and at others, it was connected to the main house. This tradition came from the Acadians, who used the attic of their homes as a bedroom for young men.

The Kitchen Yard: Daily Life Buildings

Many smaller buildings for household and farm tasks surrounded the main house. Most plantations had some or all of these outbuildings, often called "dependencies." They were usually arranged around a yard behind the main house, known as the kitchen yard. These buildings included a separate kitchen, a pantry, a washhouse (laundry), a smokehouse, a chicken house, a spring house or ice house, a milkhouse (for dairy), a covered well, and a cistern. The outhouses would have been located some distance away from the main house and kitchen yard.

The kitchen was almost always in a separate building in the South until modern times. Sometimes it was connected to the main house by a covered walkway. This separation helped keep the main house cooler in the hot climate, as cooking fires generated a lot of heat all day. It also reduced the risk of fire. In fact, many kitchens were built of brick, even if the main house was made of wood. Another reason for separating the kitchen was to keep the noise and smells of cooking away from the main house. Sometimes the kitchen building had two rooms: one for cooking and one for the cook to live in. Other times, it had a kitchen, a laundry room, and servant quarters upstairs. The pantry could be its own building or a cool part of the kitchen or a storehouse. It would hold items like barrels of salt, sugar, flour, and cornmeal.

The washhouse was where clothes, tablecloths, and bed covers were cleaned and ironed. It sometimes had living quarters for the laundrywoman. Washing clothes during this time was very hard work for the enslaved people who did it. It required special tools. A wash boiler was a large iron or copper pot where clothes and soapy water were heated over an open fire. A wash-stick was used to stir and aerate the water to loosen dirt. Items were then rubbed hard on a washboard until clean. By the 1850s, clothes were put through a mangle to squeeze out water. Before that, everything was wrung out by hand. Then, items were hung to dry or placed on a drying rack if the weather was bad. Ironing was done with a metal flat iron, often heated in the fireplace.

The milkhouse was used by enslaved people to turn milk into cream, butter, and buttermilk. First, the milk was separated into skim milk and cream. This was done by pouring whole milk into a container and letting the cream rise to the top. The cream was collected daily until there was enough. During this time, the cream would get slightly sour from natural bacteria, which helped with the churning process. Churning was hard work done with a butter churn. Once the butter was firm enough, it was taken out, washed in cold water, and salted. The churning also produced buttermilk, which was the liquid left after the butter was removed. All these products were stored in the spring house or ice house.

The smokehouse was used to preserve meat, usually pork, beef, and mutton. It was often built of logs or brick. After animals were butchered in the fall or early winter, salt and sugar were put on the meat to start the curing process. Then, the meat was slowly dried and smoked in the smokehouse by a fire that did not heat the smokehouse itself. If it was cool enough, the meat could also be stored there until it was eaten.

The chicken house was a building where chickens were kept. Its design depended on whether the chickens were for eggs, meat, or both. For eggs, there were often nest boxes for laying and perches for sleeping. Eggs were collected every day. Some plantations also had pigeonniers (dovecotes), which in Louisiana sometimes looked like tall towers near the main house. Pigeons were raised to be eaten as a special food, and their droppings were used as fertilizer.

A reliable water supply was essential for any plantation. Every plantation had at least one, and sometimes several, wells. These usually had roofs and were often partly enclosed to keep animals out. In many areas, well water tasted bad because of minerals. So, the drinking water on many plantations came from cisterns. These were supplied with rainwater collected from rooftops through pipes. Cisterns could be huge above-ground wooden barrels with metal domes, common in Louisiana and coastal Mississippi. Or they could be underground brick domes or vaults, common in other areas.

Other Important Buildings

Some buildings on plantations served extra purposes. These are also called "dependencies." A few were common, like the carriage house and blacksmith shop. But most varied a lot between plantations, depending on what the owner wanted, needed, or could afford. These buildings might include schoolhouses, offices, churches, commissary stores, gristmills (for grinding grain), and sawmills (for cutting wood).

Plantation schoolhouses were found on some plantations in every Southern state. They were places where a hired tutor or governess taught the owner's children, and sometimes children from other nearby plantations. However, on most plantations, a room in the main house was enough for schooling, rather than a separate building. Paper was expensive, so children often repeated their lessons until they memorized them. Early textbooks included the Bible, a primer, and a hornbook. As children grew older, their education prepared them for their adult roles. Boys studied school subjects, proper manners, and how to manage a plantation. Girls learned art, music, French, and the household skills needed to be the mistress of a plantation.

Most plantation owners had an office for keeping records, doing business, and writing letters. Although it was often inside the main house or another building, it was not rare for a plantation to have a separate office. John C. Calhoun used his plantation office at his Fort Hill plantation in Clemson, South Carolina, as a private space. He used it as both a study and a library during his twenty-five years there.

Another building found on some estates was a plantation chapel or church. These were built for different reasons. In many cases, the owner built a church or chapel for the enslaved people on the plantation, though they usually hired a white minister to lead the services. Some were built only for the plantation family, but many more served the family and others in the area who shared the same faith. This was especially true for owners who belonged to the Episcopal church. Early records show that at Faunsdale Plantation, the owner's wife, Louisa Harrison, regularly taught her enslaved people by reading church services and teaching the Episcopal catechism to their children. After her first husband died, she had a large Carpenter Gothic church built, called St. Michael's Church.

Most plantation churches were made of wood, though some were built of brick, often covered with stucco. Early ones were simple or in a classical style, but later ones were almost always in the Gothic Revival style. A few were as grand as churches in Southern towns. Two of the most detailed examples still existing in the Deep South are the Chapel of the Cross at Annandale Plantation and St. Mary's Chapel at Laurel Hill Plantation, both Episcopal churches in Mississippi. In both cases, the original plantation houses are gone, but the quality and design of the churches show how elaborate some plantation complexes could be. St. Mary Chapel, in Natchez, dates to 1839. It is made of stuccoed brick with large Gothic and Tudor arch windows, decorative moldings over doors and windows, buttresses, a crenelated roof-line, and a small Gothic spire.

Another building on many plantations during the sharecropping era was the plantation store or commissary. While some plantations before the Civil War had a commissary that gave food and supplies to enslaved people, the plantation store mostly appeared after the war. In addition to the part of their crop they owed the owner for using the land, tenants and sharecroppers bought food and equipment. They usually bought these on credit, promising to pay after their next crop.

This system, where people were tied to debt, affected both Black and poor white farmers. It led to a movement in the late 1800s that tried to bring Black and white people together for a common cause. This early movement is believed to have caused state governments in the South, mostly controlled by wealthy landowners, to pass laws that made it harder for poor white and Black people to vote. These laws included grandfather clauses, literacy tests, and poll taxes.

Farm Buildings

Plantations had some common farm buildings and others that varied greatly. These depended on what crops and animals were raised. Common crops included corn, upland cotton, sea island cotton, rice, sugarcane, and tobacco. Besides those mentioned, cattle, ducks, goats, hogs, and sheep were raised for their products or meat. All plantations would have had different types of animal pens, stables, and various barns. Many plantations used special buildings just for certain crops.

Plantation barns can be grouped by what they were used for, depending on the crops and animals. In the upper South, barns needed to provide shelter for animals and storage for their food, similar to barns in the North. However, most plantations in the lower South did not need to provide much shelter for animals in winter. Animals were often kept in pens with a simple shed for shelter, and the main barns were used only for storing or processing crops. Stables were an important type of barn, used to house both horses and mules. These were usually separate for each animal. The mule stable was the most important on most plantations, as mules did most of the work, pulling plows and carts.

Barns not used for animals were most commonly crib barns (for corn cribs or other types of grain storage), storage barns, or processing barns. Crib barns were typically built of logs with gaps, though sometimes they were covered with wood siding. Storage barns held unprocessed crops or those waiting to be eaten or sent to market. Processing barns were special buildings needed to prepare the crops.

Tobacco plantations were most common in parts of Georgia, Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee, South Carolina, and Virginia. The first farms in Virginia were founded on growing tobacco. Tobacco farming was very labor-intensive. It took all year to gather seeds, start them in special frames, and then plant them in the fields once the soil was warm. Then, enslaved people had to weed the fields all summer and remove the flowers from the tobacco plants to make the leaves grow bigger. Harvesting was done by picking individual leaves over several weeks as they ripened, or by cutting whole tobacco plants and hanging them in vented tobacco barns to dry, a process called curing.

Rice plantations were common in the South Carolina Lowcountry. Until the 1800s, rice was separated from its stalks and the husk was removed from the grain by hand, which was very hard work. By the 1830s, steam-powered rice pounding mills became common. They were used to separate the grain from the inedible outer layer (chaff). A separate chimney, needed for the fires powering the steam engine, was next to the pounding mill and often connected by an underground system. The winnowing barn, a building raised about one story off the ground on posts, was used to separate the lighter chaff and dust from the rice.

Sugar plantations were most commonly found in Louisiana. In fact, Louisiana produced almost all the sugar grown in the United States before the Civil War. About one-quarter to one-half of all sugar eaten in the United States came from Louisiana sugar plantations. Plantations grew sugarcane from Louisiana's early days, but large-scale production didn't start until the 1810s and 1820s. A successful sugar plantation needed skilled hired workers and enslaved people.

The most specialized building on a sugar plantation was the sugar mill (sugar house). By the 1830s, a steam-powered mill crushed the sugarcane stalks between rollers. This squeezed the juice from the stalks, and the juice flowed out the bottom through a strainer into a tank. From there, the juice went through a process to remove impurities and thicken it by evaporating water. It was heated with steam in large vats, where more impurities were removed by adding lime. Then the mixture was strained. At this point, the liquid had become molasses. It was then put into a closed container called a vacuum pan, where it was boiled until the sugar in the syrup turned into crystals. The crystallized sugar was then cooled and separated from any remaining molasses in a process called purging. The final step was packing the sugar into large barrels called hogsheads for transport to market.

Cotton plantations were the most common type of plantation in the South before the Civil War. They were also the last type of plantation to fully develop. Cotton production was very labor-intensive to harvest, as the fibers had to be picked by hand from the bolls. This was combined with the equally hard work of removing seeds from the fiber by hand.

After the invention of the cotton gin, cotton plantations grew rapidly across the South. Cotton production soared, and so did the expansion of slavery. Cotton also caused plantations to grow in size. During financial problems in 1819 and 1837, when British mills needed less cotton, many small plantation owners went bankrupt. Their land and enslaved people were bought by larger plantations. As cotton-producing estates grew, so did the number of people who owned enslaved people and the average number of enslaved people they held.

A cotton plantation usually had a cotton gin house, where the cotton gin was used to remove seeds from raw cotton. After ginning, the cotton had to be baled before it could be stored and sent to market. This was done with a cotton press, an early type of baler. It was usually powered by two mules walking in a circle, each attached to an overhead arm that turned a huge wooden screw. This screw pressed the processed cotton into a uniform bale shape inside a wooden enclosure, where the bale was tied with twine.

Plantation Complexes Today

Many main plantation houses still exist. In some cases, former homes for enslaved people have been rebuilt or fixed up. To help pay for their upkeep, some, like the Monmouth Plantation in Natchez, Mississippi and the Lipscomb Plantation in Durham, North Carolina, have become small luxury hotels or bed and breakfasts. Not only Monticello and Mount Vernon, but about 375 former plantation houses are now museums that people can visit. There are examples in every Southern state. Places like Natchez offer tours of plantations.

Traditionally, these museum houses showed a romantic, idealized view of the time before the Civil War. More recently, and to different degrees, some have started to acknowledge the difficult history of slavery that made that life possible.

In late 2019, after discussions started by Color of Change, "five major websites often used for wedding planning promised to reduce promoting and romanticizing weddings at former slave plantations." The New York Times, earlier in 2019, "decided...to not include couples who were getting married on plantations in wedding announcements and other wedding coverage."

People on the Plantation

The Plantation Owner

A person who owned a plantation was known as a planter. Historians of the Southern United States before the Civil War usually define a "planter" as someone who owned land and 20 or more enslaved people. In some areas, like the "Black Belt" counties of Alabama and Mississippi, the words "planter" and "farmer" often meant the same thing.

Historians Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman define large planters as those owning over 50 enslaved people, and medium planters as those owning between 16 and 50 enslaved people. Historian David Williams suggests that owning at least twenty enslaved people was the minimum for planter status. This was partly because a Southern planter could avoid fighting in the Confederate army for every twenty enslaved people they owned.

Many older books about plantation life were published after the Civil War. For example, James Battle Avirett, who grew up on the Avirett-Stephens Plantation in Onslow County, North Carolina, wrote The Old Plantation: How We Lived in Great House and Cabin before the War in 1901. Such books often described Christmas as a perfect example of the old way of life, centered around the "great house" and extended family.

Novels, often made into films, presented a romantic and simplified view of plantation life. The most popular of these were The Birth of a Nation (1916) and Gone with the Wind (1939).

The Overseer

On larger plantations, an overseer managed things day-to-day for the owner. Overseers were often seen as rough and not well-educated. Their job was to enforce rules and give out punishments to keep discipline and ensure the plantation made money for the owner.

Slavery on Plantations

Southern plantations relied on enslaved people to do all the farm work. As an employee of the Whitney Plantation said in 2019, "Honestly, 'plantation' and 'slavery' is one and the same."

Many plantations, including George Washington's Mount Vernon and Thomas Jefferson's Monticello, are now working to show a more accurate picture of what life was like for both enslaved people and owners. These changes have started to attract people who felt disconnected by the old, simplified stories. Staff say there is a desire for real history. Plantations are now adding tours that focus on slavery, rebuilding cabins, and recreating the lives of enslaved people with help from their descendants.

McLeod Plantation mainly focuses on the history of slavery. "McLeod focuses on forced labor, speaking openly about 'slave labor camps' and highlighting the fields rather than just the big white house." One review posted to Twitter said, "I was sad by the time I left and wondered why anyone would want to live in South Carolina."

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |