Thomas Jefferson and slavery facts for kids

Thomas Jefferson, who was the third president of the United States, owned over 600 enslaved people during his life. He freed two enslaved people while he was alive. Five more were freed after his death. This included two of his children from his relationship with Sally Hemings, who was also enslaved. His other two children with Hemings were allowed to leave without being chased. After Jefferson died, most of the enslaved people were sold to pay off his debts.

One reason Jefferson did not free more enslaved people was his large debt. He also publicly said he feared that freeing enslaved people into American society would cause problems between white people and formerly enslaved people.

Jefferson always spoke out against the international slave trade. He made it illegal when he was president. He believed in a slow freeing of all enslaved people in the U.S. He also supported the idea of sending freed African Americans to Africa. However, he often opposed rules that would limit slavery within the U.S. He also criticized people who chose to free their own enslaved people.

Contents

- Early Life and Slavery (1743–1774)

- Revolutionary Times and Slavery (1775–1783)

- After the Revolution (1784–1800)

- Jefferson as President (1801–1809)

- Retirement Years (1810–1826)

- After Jefferson's Death (1827–1830)

- Sally Hemings and Her Children

- Life for Enslaved People at Monticello

- Historians' Views on Jefferson and Slavery

- See also

Early Life and Slavery (1743–1774)

Thomas Jefferson was born in 1743 into a wealthy family that owned plantations. In his time, slavery was the main way people worked on farms. His father, Peter Jefferson, was a well-known slave owner and land investor in Virginia. His mother, Jane Randolph, came from a respected English and Scottish family.

In 1757, when Jefferson was 14, his father died. Jefferson inherited about 5,000 acres of land, 52 enslaved people, animals, his father's large library, and a mill. He took full control of these properties when he was 21. In 1768, Jefferson started building his famous home, Monticello. It was a large house built in a classical style, overlooking his childhood home.

As a lawyer, Jefferson represented both white and Black people. In 1770, he defended a young mixed-race enslaved man. Jefferson argued that the man's mother was white and free, so the man should also be free. This was based on a law that said a child's status followed the mother's. Jefferson lost this case. In 1772, he helped George Manly, a free Black man. Manly sued for his freedom after being forced to work for three years longer than he should have been. After being freed, Manly worked for Jefferson at Monticello for pay.

In 1773, Jefferson married Martha Wayles Skelton. Her father died that same year. Jefferson and Martha inherited his estate, which included 11,000 acres, 135 enslaved people, and £4,000 in debt. This inheritance made Jefferson one of the biggest slave owners in Albemarle County. He also owned nearly 16,000 acres of land in Virginia. He sold some enslaved people to help pay off his father-in-law's debt. From then on, Jefferson managed his large plantations, mostly at Monticello. Slavery was key to the lifestyle of wealthy landowners in Virginia.

The National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., had an exhibit called Slavery at Jefferson's Monticello: The Paradox of Liberty in 2012. It focused on Jefferson as a slave owner and the roughly 600 enslaved people who lived at Monticello. It highlighted six enslaved families and their descendants. Monticello also opened an outdoor exhibit, Landscape of Slavery: Mulberry Row at Monticello. This exhibit shares the stories of the many enslaved and free people who lived and worked on Jefferson's plantation.

In 1774, Jefferson wrote A Summary View of the Rights of British America. He argued that Americans should have all the rights of British citizens. He criticized King George III for unfairly taking power in the colonies. About slavery, Jefferson wrote that ending it was a big goal for the colonies. He said that stopping new enslaved people from Africa was needed before freeing those already there. He blamed the King for blocking efforts to stop the slave trade.

Revolutionary Times and Slavery (1775–1783)

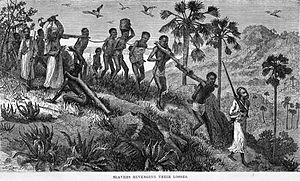

In 1775, Thomas Jefferson joined the Continental Congress. This was when people in Virginia began to fight against the British governor, Lord Dunmore. In November 1775, Dunmore offered freedom to enslaved people who left their American owners and joined the British. This led to thousands of enslaved people escaping from plantations in the South during the war. Some of the people Jefferson enslaved also ran away.

The colonists saw Dunmore's action as an attempt to start a huge slave rebellion. In 1776, when Jefferson helped write the Declaration of Independence, he mentioned Dunmore. He wrote, "He has excited domestic insurrections among us." However, the document never directly named slavery. In an early version, Jefferson included a part that condemned King George III for forcing the slave trade on the colonies. It also accused the King of encouraging enslaved African Americans to fight against their owners.

However, Southern colonies opposed this part. So, the Continental Congress made Jefferson remove it from the final Declaration. Jefferson did manage to include a general statement against slavery by keeping "all men are created equal." Jefferson himself owned enslaved people, so he did not directly condemn slavery in the Declaration.

That same year, Jefferson suggested a new Virginia Constitution. It included the phrase, "No person hereafter coming into this country shall be held within the same in slavery under any pretext whatever." His idea was not accepted.

In 1778, with Jefferson's leadership, Virginia banned importing enslaved people. It was one of the first places in the world to ban the international slave trade. All other states except South Carolina eventually followed before Congress banned the trade in 1807.

As governor of Virginia during the Revolution, Jefferson signed a bill. It offered land or money to white men who joined the military. He also brought some enslaved household workers, including Mary Hemings, to serve in the governor's mansion. In January 1781, facing a British invasion, Jefferson and the government fled. They left the enslaved workers behind. The British took Hemings and other enslaved people as prisoners. They were later freed in exchange for British soldiers. In 2009, the Daughters of the American Revolution honored Mary Hemings as a Patriot.

In June 1781, the British arrived at Monticello. Jefferson had already escaped with his family to another plantation. Most of the enslaved people stayed at Monticello to help protect his belongings. The British did not loot or take prisoners there. However, Lord Cornwallis and his troops looted another of Jefferson's plantations. Of the 30 enslaved people they took as prisoners, Jefferson later said at least 27 died from disease.

Jefferson said he supported freeing enslaved people slowly since the 1770s. But as a member of the Virginia General Assembly, he did not support a law to do this. He said people were not ready. After the U.S. became independent, Virginia made it easier for slave owners to free enslaved people in 1782. Unlike some other slave owners, Jefferson formally freed only two people during his life. Virginia did not require freed people to leave the state until 1806. From 1782 to 1810, the number of free Black people in Virginia grew a lot.

After the Revolution (1784–1800)

Some historians have said that Jefferson tried to abolish slavery as a Representative to the Continental Congress. However, according to historian Paul Finkelman, Jefferson "never did propose this plan." He also "refused to propose either a gradual emancipation scheme or a bill to allow individual masters to free their slaves." He said it was "better that this should be kept back." In 1785, Jefferson wrote that Black people were not as smart as white people. He claimed the entire race could not produce a single poet.

On March 1, 1784, Jefferson proposed a plan for governing the western territories. This plan would have banned slavery in *all* new states formed from these lands. This included areas that would become Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee. His plan would have completely banned slavery by 1800 in all territories. But it was rejected by Congress by just one vote. Jefferson said Southern representatives defeated his idea. The Library of Congress notes that this plan was the strongest Jefferson's opposition to slavery ever was.

In 1785, Jefferson published his first book, Notes on the State of Virginia. In it, he wrote that Black people were not as good as white people. He also said that these ideas were not certain. Jefferson believed that freeing enslaved people and sending them away from America was the best plan. He also warned about possible slave rebellions in the future. He wrote, "I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just."

From the 1770s on, Jefferson wrote about supporting gradual emancipation. He thought enslaved people should be educated and freed after a certain age. Then they should be sent to Africa. He supported the idea of colonizing Africa with American freedmen his whole life. Some historians suggest that after having children with Sally Hemings, Jefferson might have supported colonization because he worried about his unacknowledged family.

Historian David Brion Davis says that after 1785, Jefferson became very quiet about slavery. Davis believes Jefferson had inner conflicts about slavery. He also wanted to keep his personal situation private. Because of this, he stopped working to end slavery.

As U.S. Secretary of State, Jefferson helped French slave owners in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) in 1795. He sent them money and weapons to stop a slave rebellion. This was approved by President Washington.

In September 1800, Virginia governor James Monroe told Jefferson about a slave rebellion led by Gabriel Prosser that was stopped. Ten of the rebels had already been executed. Monroe asked Jefferson for advice on what to do with the rest. Jefferson replied, urging Monroe to send the remaining rebels away instead of executing them. Jefferson's letter suggested the rebels had some reason for fighting for freedom. He wrote that the world would "for ever condemn us if we indulge a principle of revenge." By the time Monroe got the letter, 20 rebels had been executed. Seven more were executed later, including Prosser. But 50 others charged for the rebellion were found not guilty or had their sentences changed.

Jefferson as President (1801–1809)

In 1800, Jefferson was elected President. He won more votes than John Adams, partly because of support from Southern states. The Constitution counted enslaved people as three-fifths of a person for population counts. This gave states with many enslaved people more power in Congress and in presidential elections. Jefferson won the election because of this advantage.

Enslaved People at the White House

Jefferson brought enslaved people from Monticello to work at the White House. He brought Edith Hern Fossett and Fanny Hern to Washington, D.C., in 1802. They learned to cook French food from Honoré Julien. Edith was 15 and Fanny was 18. They were the only enslaved people from Monticello to live regularly in Washington. They did not get a wage, but they received a two-dollar tip each month. They worked in Washington for almost seven years. Edith had three children there, and Fanny had one. Their children stayed with them at the President's House.

Haiti's Independence

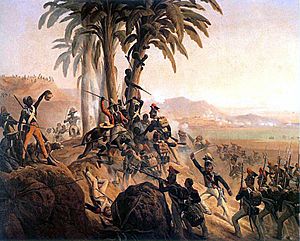

- Further information: Haitian Revolution

After Toussaint Louverture became governor of Saint-Domingue following a slave revolt, Jefferson supported French plans to take back the island in 1801. He agreed to loan France money to help white people on the island. Jefferson wanted to calm the fears of Southern slave owners, who worried about similar rebellions. Before becoming president, Jefferson wrote about the revolution, "If something is not done and soon, we shall be the murderers of our own children."

By 1802, Jefferson learned that France planned to rebuild its empire in the Western Hemisphere. This included taking the Louisiana Territory and New Orleans from Spain. Jefferson declared that the U.S. would be neutral in the Caribbean conflict. He refused to give credit or help to the French. But he allowed illegal goods and weapons to reach Haiti. This indirectly supported the Haitian Revolution. This also helped U.S. interests in Louisiana.

After Haiti declared independence in 1804, President Jefferson had to deal with strong opposition from Congress, which was controlled by Southern states. He shared the slave owners' fears that Haiti's success would encourage slave rebellions in the South. Jefferson discouraged free Black Americans from moving to Haiti. European nations also refused to recognize Haiti's independence.

Jefferson had mixed feelings about Haiti. During his presidency, he thought sending free Black people and rebellious enslaved people to Haiti might solve some U.S. problems. He hoped Haiti would show that Black people could govern themselves. This would justify freeing and sending enslaved people to the island. In 1824, Jefferson told a visitor that he had never seen Black people govern themselves well. He thought they would not do it without white help.

Virginia's Emancipation Law Changed

In 1806, Virginia became worried about the growing number of free Black people. The Virginia General Assembly changed the 1782 slave law. It made it harder for free Black people to live in the state. It allowed newly freed people to be re-enslaved if they stayed in Virginia for more than 12 months. This forced newly freed Black people to leave their enslaved family members behind. Slave owners had to ask the legislature directly for permission for freed people to stay. This led to fewer enslaved people being freed after this date.

Ending the International Slave Trade

In 1808, Jefferson spoke out against the international slave trade. He called for a law to make it a crime. He told Congress in 1806 that such a law was needed to stop U.S. citizens from taking part in "violations of human rights." On March 2, 1807, Jefferson signed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves into law. It took effect on January 1, 1808. It made it a federal crime to import or export enslaved people from other countries.

By 1808, every state except South Carolina had already banned importing enslaved people. By then, the number of enslaved people in the U.S. had grown. This led to a large internal slave trade within the country. So, slave owners did not strongly resist the new law. The end of international trade also made existing enslaved people more valuable. Jefferson did not lead the effort to ban the import of enslaved people.

Retirement Years (1810–1826)

In 1819, Jefferson strongly opposed a change to Missouri's statehood application. This change would have banned importing enslaved people and freed them at age 25. He believed it would break up the country. By 1820, Jefferson disliked what he saw as "Northern meddling" with Southern slavery. On April 22, he criticized the Missouri Compromise. He feared it would lead to the Union breaking apart. Jefferson said slavery was a complex issue that the next generation needed to solve. He called the Missouri Compromise a "fire bell in the night" and "the knell of the Union." He wrote that he now doubted the Union would last long.

In 1798, Jefferson's friend, Tadeusz Kościuszko, a Polish nobleman, visited the U.S. He left his money to Jefferson in a will. He wanted Jefferson to use the money to free and educate enslaved people, including Jefferson's own. Kościuszko died in 1817. But Jefferson never carried out the will. He said he was too old and the will had many legal problems. The will was fought over in court for years, even after Jefferson died. In 1852, the U.S. Supreme Court gave the money to Kościuszko's family in Poland.

Jefferson continued to have large debts after being president. He used some of his hundreds of enslaved people as security for his loans. His debt was due to his expensive lifestyle, constant building at Monticello, and inherited debt. He also helped support his daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, and her large family.

In August 1814, Jefferson exchanged letters with Edward Coles about Coles' ideas on freeing enslaved people. Jefferson urged Coles not to free his enslaved people. But Coles took all his enslaved people to Illinois and freed them. He gave them land for farms.

In April 1820, Jefferson wrote about the Missouri Compromise. About slavery, he said, "there is not a man on earth who would sacrifice more than I would, to relieve us from this heavy reproach [slavery]... we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other. " Jefferson compared slavery to a dangerous animal that could not be controlled or freed. He believed that trying to end slavery would lead to violence. He wrote that he regretted he would die believing that the efforts of his generation to gain self-government would be wasted. After the Missouri Compromise, Jefferson mostly stayed out of politics.

In 1821, Jefferson wrote in his autobiography that slavery would eventually end. But he also felt there was no hope for racial equality in America. He wrote, "Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that these people [Black people] are to be free." But he also said, "Nor is it less certain that the two races, equally free, cannot live in the same government." He believed that Black and white people could not live together peacefully if both were free. He thought that freeing enslaved people and sending them away slowly would be best. If not, he feared terrible outcomes.

The U.S. Congress passed the Slave Trade Act of 1819. This law allowed money to be used to send freed African American enslaved people to Africa. In 1824, Jefferson suggested a plan to free enslaved people born after a certain date. He proposed that the government buy African-American children for $12.50 and send them to Santo Domingo. Jefferson knew his plan might be unconstitutional. But he suggested a change to the Constitution to allow Congress to buy enslaved people. He also knew that separating children from their families would be hard. But he believed freeing over a million enslaved people was worth the financial and emotional costs.

After Jefferson's Death (1827–1830)

When Jefferson died, he was deeply in debt. His family had to sell 130 enslaved people from Monticello to pay his creditors. This included almost all members of every enslaved family. Families who had lived together for decades were sometimes split up. Most of the enslaved people sold stayed in Virginia or were moved to Ohio.

Jefferson freed five enslaved men in his will. All were from the Hemings family. These included his two sons, John Hemings, and his nephews Joseph (Joe) Fossett and Burwell Colbert. He gave Burwell Colbert, his butler, $300 for painting supplies. He gave John Hemings and Joe Fossett each an acre of land to build homes. His will asked the state to let these freedmen stay in Virginia with their families, who remained enslaved by Jefferson's heirs.

Jefferson freed Joseph Fossett in his will. But Fossett's wife, Edith Hern Fossett, and their eight children were sold at auction. Fossett managed to get enough money to buy his wife's freedom and their two youngest children. The rest of their children were sold to different slave owners. The Fossetts worked for 23 years to buy the freedom of their remaining children.

Born and reared as free, not knowing that I was a slave, then suddenly, at the death of Jefferson, put upon an auction block and sold to strangers.

In 1827, the auction of 130 enslaved people took place at Monticello. The sale lasted five days. The enslaved people sold for more than 70% of their estimated value. Within three years, all the enslaved families at Monticello had been sold and separated.

Sally Hemings and Her Children

For two centuries, people have discussed whether Thomas Jefferson had children with his enslaved woman, Sally Hemings. In 1802, a journalist claimed that Jefferson had a relationship with Hemings and had several children with her. Sally Hemings was the daughter of John Wayles, who was also Jefferson's father-in-law. Sally was three-quarters white and looked and sounded very much like Jefferson's late wife.

In 1998, scientists did a DNA study to check the male family line. They compared DNA from Jefferson's uncle's descendants with a descendant of Sally's son, Eston Hemings. The results showed a DNA match with the male Jefferson line. In 2000, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation (TJF) concluded that, with the DNA and historical evidence, it was very likely Jefferson was the father of Eston and probably all of Hemings' children.

Since the DNA tests were made public, most historians believe that Jefferson had a long relationship with Hemings. They also believe he fathered at least some, and likely all, of her children. A few scholars still believe there isn't enough evidence to be sure. They point out that other Jefferson men, like Thomas's brother Randolph Jefferson and his sons, could have been the fathers.

Jefferson allowed two of Sally's children to leave Monticello without being formally freed when they became adults. Five other enslaved people, including Sally's two remaining sons, were freed by his will after his death. Although not legally freed, Sally left Monticello with her sons. They were listed as free white people in the 1830 census. Madison Hemings, one of Sally's sons, claimed in a newspaper article that Jefferson was his father.

Life for Enslaved People at Monticello

Jefferson managed all four Monticello farms. He gave detailed instructions to his overseers when he was away. He hired many overseers, some of whom were known to be cruel. Jefferson kept careful records of his enslaved people, plants, animals, and the weather. In his Farm Book journal, he described the clothing bought for enslaved people and listed who received it. In 1811, he wrote about his stress in trying to get specific blankets for "those poor creatures" – his enslaved people.

Some historians note that Jefferson kept many enslaved families together on his plantations. This was common for slave owners at the time. Often, more than one generation of a family lived on the plantation, and families were stable. Jefferson and other slave owners shifted the cost of having more workers to the enslaved people themselves. He could increase the value of his property without buying more enslaved people. He tried to reduce infant deaths. He wrote that "a woman who brings a child every two years is more profitable than the best man on the farm."

Jefferson encouraged enslaved people at Monticello to "marry." (Enslaved people could not legally marry in Virginia.) He would sometimes buy and sell enslaved people to keep families together. In 1815, he said his enslaved people were "worth a great deal more" because of their marriages. However, "married" enslaved people had no legal protection. Owners could separate "husbands" and "wives" whenever they wanted.

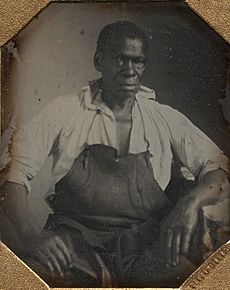

Thomas Jefferson wrote about his plan for employing children in his Farm Book. Until age 10, children worked as nurses. When the plantation grew tobacco, children were the right height to remove worms from the crops. When he started growing wheat, fewer people were needed for crops. So, Jefferson started manual trades. He said children "go into the ground or learn trades." Girls aged 16 began spinning and weaving cloth. Boys aged 10 to 16 made nails. In 1794, Jefferson had a dozen boys working at the nail factory. He chose the most productive boys to be trained as skilled workers like blacksmiths and carpenters. Those who did the worst were sent to work in the fields. Boys working at the nailery received more food and sometimes new clothes for good work.

James Hubbard was an enslaved worker in the nailery who ran away twice. The first time, Jefferson did not have him whipped. But the second time, Jefferson reportedly ordered him severely whipped. Hubbard was likely sold after being jailed. Physical violence was common on plantations, including Jefferson's. Historian Henry Wiencek noted reports of Jefferson ordering enslaved people to be whipped or sold as punishment for bad behavior or escape.

The Thomas Jefferson Foundation says Jefferson told his overseers not to whip his enslaved people. But they often ignored his wishes when he was away. No reliable document shows Jefferson directly using physical punishment. During Jefferson's time, some other slave owners also disagreed with whipping and jailing enslaved people.

Enslaved people had many different jobs. Davy Bowles was the carriage driver, taking Jefferson to and from Washington, D.C. or the Virginia capital. Betty Hemings, an enslaved woman inherited from Jefferson's father-in-law, was the head of the house enslaved people at Monticello. She and her family were allowed some freedom when Jefferson was away. Four of her daughters worked in the house, including Sally Hemings. Two of Sally's daughters were half-sisters to Jefferson's wife, and Sally had six children with Jefferson. Other enslaved people included Ursula Granger, a house slave Jefferson bought. Hemings family members also handled general maintenance of the mansion. Betty's son, John Hemings, was the master carpenter. His nephews, Joe Fossett (blacksmith) and Burwell Colbert (butler and painter), also had important roles. Wormley Hughes, a grandson of Betty Hemings and a gardener, was informally freed after Jefferson's death.

Memoirs of life at Monticello include those by Isaac Jefferson (published 1843), Madison Hemings, and Israel Jefferson (both published 1873). Isaac was an enslaved blacksmith on Jefferson's plantation.

The last recorded interview with a former enslaved person was with Fountain Hughes in 1949. He was 101 and lived in Baltimore, Maryland. He was a descendant of Wormley Hughes and Ursula Granger. His grandparents were among the enslaved people owned by Jefferson at Monticello.

Historians' Views on Jefferson and Slavery

According to historian James W. Loewen, Jefferson "wrestled with slavery, even though in the end he lost." Loewen says understanding Jefferson's relationship with slavery helps understand current American social issues.

Many important historians of the 20th century, like Merrill Peterson, believed Jefferson strongly opposed slavery. Peterson said Jefferson owning enslaved people "placed him at odds with his moral and political principles." But he added there was "no question of his genuine hatred of slavery." Peter Onuf stated that Jefferson was known for his "opposition to slavery." Onuf and his colleague Ari Helo suggested that Jefferson opposed Black and white people living together. This, they argued, made immediate freedom for enslaved people difficult for Jefferson. They said Jefferson feared that freeing enslaved people in white areas would cause "genocidal violence." He could not imagine the two groups living peacefully. Onuf and Helo believed Jefferson supported freeing African Americans by "expulsion," which he thought would keep both groups safe. Biographer John Ferling said Thomas Jefferson was "zealously committed to slavery's abolition."

Starting in the early 1960s, some scholars began to question Jefferson's role as an anti-slavery advocate. They re-examined his actions and words. Paul Finkelman wrote in 1994 that earlier scholars "exaggerate or misrepresent" to support Jefferson's anti-slavery stance. He said they "ignore contrary evidence" and "paint a false picture" to protect Jefferson's image.

In 2012, author Henry Wiencek, who is critical of Jefferson, concluded that Jefferson tried to protect his image as a Founding Father. He did this by hiding slavery from visitors at Monticello and in his writings to abolitionists. Wiencek believed Jefferson made a new road to Monticello to hide the overseers and enslaved people working in the fields. Wiencek thought Jefferson's "soft answers" to abolitionists made him seem opposed to slavery. Wiencek stated that Jefferson had huge political power but "did nothing to hasten slavery's end" during his time as a diplomat, secretary of state, vice president, or president.

According to Greg Warnusz, Jefferson held common 19th-century beliefs that Black people were not as good as white people for citizenship. He wanted them sent back to Liberia and other colonies. His idea of a democratic society was based on white working men. He claimed to want to help both races. He suggested slowly freeing enslaved people after age 45 (when they would have paid back their owner's investment). Then they would be sent to Africa. Jefferson's plan imagined a society with only white people.

Historian Annette Gordon-Reed said, "Of all the Founding Fathers, it was Thomas Jefferson for whom the issue of race loomed largest." She noted that as a slave owner, public official, and family man, he thought about and wrote about the relationship between Black and white people his whole life.

Paul Finkelman claims that Jefferson believed Black people lacked basic human emotions.

According to historian Jeremy J. Tewell, Jefferson viewed slavery as a "Southern way of life." He believed slavery protected Black people, whom he saw as unable to care for themselves.

According to Joyce Appleby, Jefferson had chances to distance himself from slavery. In 1782, Virginia passed a law making it easier for slave owners to free enslaved people. The rate of freeing enslaved people increased in other Southern states too. Northern states passed various plans to end slavery. But Jefferson's actions did not keep up with those who wanted to end slavery. On September 15, 1793, Jefferson agreed to free James Hemings, his mixed-race enslaved chef. This was after James trained his younger brother Peter as a replacement. Jefferson finally freed James Hemings in February 1796. One historian said Jefferson's freeing of James was not generous.

In contrast, enough other slave owners in Virginia freed enslaved people in the first two decades after the Revolution. This caused the number of free Black people in Virginia to grow from less than 1% in 1790 to 7.2% in 1810.

|

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Jefferson y la esclavitud para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Jefferson y la esclavitud para niños

- List of presidents of the United States who owned slaves

- Memorial to Enslaved Laborers

- - including enslaved people with the surnames Colbert, Fossett, Hemings, and Jefferson

- Thomas Jefferson and Native Americans

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |