Isaac Jefferson facts for kids

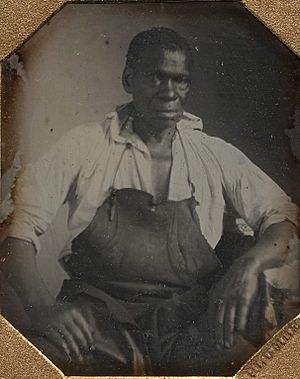

Isaac Jefferson, also known as Isaac Granger (born in 1775, died in 1846), was an important enslaved artisan who worked for US President Thomas Jefferson. He was skilled in making and fixing things as a tinsmith, blacksmith, and nail maker at Jefferson's home, Monticello.

Even though Thomas Jefferson gave Isaac and his family to his daughter Maria and her husband John Wayles Eppes in 1797 as a wedding gift, Isaac likely became a free man by 1822. This is known from his own story, called a memoir. In 1840, official records showed him as Isaac Granger, a free man working in Petersburg, Virginia. A minister named Charles Campbell interviewed him there. Campbell later published Isaac's story in 1847, a year after Isaac died, using the name Isaac Jefferson. In his memoir, Isaac described Thomas Jefferson as his owner and shared details about the lives of the enslaved people.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Isaac was born into slavery in 1775. He was the fourth son of Ursula Granger and Great George. His father, Great George, became the overseer at Monticello in 1797. This was a very important job, and he was the only enslaved person to hold this position under Thomas Jefferson.

Isaac's mother, Ursula, was bought by Jefferson in 1773. She was a trusted house servant who worked as a pastry cook and laundress. She also helped with preserving meat and bottling cider. Isaac had two older brothers named George and Bagwell.

Childhood Experiences

Isaac grew up on the Monticello plantation. When he was young, his jobs included carrying fuel, lighting fires, and opening gates. When Thomas Jefferson became Governor of Virginia, he took Great George, Ursula, and their family with him to Williamsburg and Richmond.

Because of this, young Isaac saw many important events during the American Revolutionary War. He later remembered seeing Benedict Arnold's attack on Richmond in 1781. He also saw the camp for captured enslaved people at Yorktown.

Learning Skills at Monticello

Around 1790, when Isaac was about 15 years old, he started his apprentice training. This meant he learned skills in working with metal. When Thomas Jefferson became president, he took Isaac with him to Philadelphia. There, Isaac was trained for several years by a tinsmith. This was a valuable and important skill.

Isaac's own story is the only way we know about this part of his life. He learned to make things like graters, pepper boxes, and tin cups. He could make about four dozen of these every day.

Working as a Blacksmith and Nailer

After returning to Monticello, President Jefferson set up a tin shop. Isaac Granger/Jefferson remembered that this shop did not make much money. So, Isaac learned more skills by training as a blacksmith under his older brother, Little George.

After 1794, Isaac also became a nailer. This meant he made nails. He worked in both nail making and blacksmithing.

Marriage and Family Life

By 1796, Isaac Granger was married to a woman named Iris. They had a son named Joyce. Isaac worked extra hours in the blacksmith shop to make chain traces. Thomas Jefferson paid him for this extra work.

Jefferson's records show that Isaac Granger was a very good nailer. In the first three months of 1796, he made 507 pounds of nails in 47 days. He wasted the least amount of metal rods in the process. He earned the highest daily profit for his owner, which was like eighty-five cents a day.

Leaving Monticello

In October 1797, Thomas Jefferson gave Isaac, his wife Iris, and their sons Joyce and Squire to his daughter Maria and John Wayles Eppes. This was part of their marriage agreement. It was a common practice for plantation owners who had many enslaved people. Jefferson also gave the Eppes family a 14-year-old enslaved girl named Betsy Hemmings. She would become the nurse for their children and an important figure among the enslaved community at the Eppes plantation, Mont Blanco.

New Locations

Later, when Jefferson's son-in-law Thomas Mann Randolph Jr. needed a blacksmith, he rented Isaac from Eppes. So, Isaac and his young family moved from Eppes's plantation in Buckingham County, Virginia to the Randolph plantation of Edgehill in Albemarle County, Virginia in 1798. Their daughter, Maria, was born soon after.

Isaac's memoir suggests he lived at Monticello during Jefferson's later years, after Jefferson retired. Isaac and his family might have gone with Martha Jefferson Randolph, Jefferson's daughter, and her children in 1809 when she moved to Monticello to help her father.

Family Losses

In 1799 and 1800, Isaac's parents and his brother Little George all died within a few months. When they were sick, the family members sought help from a black conjurer (a person believed to have special powers) living in Buckingham County. This shows how African traditions continued within the enslaved community. After Great George died, Thomas Jefferson gave Isaac $11. This was the value of his share of a young horse left to him by his father.

In 1812, an enslaved man named Isaac who belonged to Thomas Mann Randolph ran away and was caught. It is not known if this was Isaac the blacksmith. Randolph owned at least one other enslaved person named Isaac during this time.

Freedom and His Memoir

We do not know exactly how Isaac became free. His memoir says he left Albemarle County, Virginia about four years before Jefferson died, which would be around 1822. In 1824, he met and spoke with the French general, the Marquis de Lafayette, in Richmond.

Recent studies by the staff at Monticello suggest that Isaac Jefferson might have used the name Isaac Granger after becoming free, or even before that within the enslaved community. Someone else might have later mistakenly given him the name Jefferson. The 1840 census for Petersburg, Virginia lists a free black man named Isaac Granger. His family members and age match what is known about Isaac Jefferson.

Sharing His Story

In the early 1840s, Isaac Granger was working as a free blacksmith in Petersburg. This is when Charles Campbell interviewed him. Campbell published Isaac's story that year as the memoir of Isaac Jefferson. Granger did not say if he chose the last name Jefferson or if a white person gave it to him, as happened with another enslaved person from Monticello, Israel Jefferson.

The memoir was found again and published in 1951 by historian Rayford Logan. In the interview, Granger shared details about Thomas Jefferson and the Hemings family. He said that "folks said that" Sally Hemings and some of her siblings "was old Mr. Wayles' children." This referred to Jefferson's father-in-law, John Wayles. Some historians believe this supports other historical accounts that Sally Hemings and her five full siblings were half-siblings of Jefferson's wife, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson. The memoir describes how important the Betty Hemings family was at Monticello. They worked as house servants, skilled artisans, and staff who managed the president's home.

The future of Isaac's first wife, Iris, and their two sons is unknown. In the 1840s, when he shared his story, Isaac was married to his second wife. Reverend Charles Campbell wrote that Isaac Jefferson died "a few years after these his recollections were taken down. He bore a good character." Campbell might have used the name Jefferson to make the published memoir more popular.

Isaac Jefferson died in 1846. A document from August 20, 1846, states that "Isaac Jefferson having been dead more than three months & no person having applied for administration of his estate, it is ordered that the same be committed to J Branch Sergt. of this town to be by him administered according to law."

The Granger Name

The Monticello staff found another mention of the Granger last name in old records. In the 1870 census for Albemarle County, an Archy Granger and his family were living at Edgehill Plantation. This plantation was owned by Thomas Jefferson Randolph, who was Thomas Jefferson's grandson. They worked for Randolph's sister, Septimia Randolph Meikleham.

Thomas J. Randolph had bought Archy from Monticello after his grandfather Jefferson died in 1826. At that time, 130 enslaved people were sold to pay off debts from Jefferson's estate. Archy Granger's age matches the plantation records for Archy, who was the son of enslaved people named Bagwell and Minerva from Monticello. He was also the grandson of Great George and Ursula. Letters from the Randolph family also mention an Archy Granger and his family at their Edgehill plantation. He appears to have been Isaac (Jefferson) Granger's nephew. His use of the Granger name further suggests it was a name used within the family.

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |