Monticello facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Monticello |

|

|---|---|

Monticello in September 2013

|

|

| Location | Albemarle County, Virginia near Charlottesville, Virginia, U.S. |

| Built | 1772 |

| Architect | Thomas Jefferson |

| Architectural style(s) | Neoclassical, Palladian |

| Governing body | The Thomas Jefferson Foundation (TJF) |

| Official name: Monticello and the University of Virginia in Charlottesville | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iv, vi |

| Designated | 1987 (11th session) |

| Reference no. | 442 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Designated | October 15, 1966 |

| Reference no. | 66000826 |

| Designated | December 19, 1960 |

| Designated | September 9, 1969 |

| Reference no. | 002-0050 |

Monticello (pronounced MON-tih-CHEL-oh) was the main home and large farm of Thomas Jefferson. He was a Founding Father, wrote the Declaration of Independence, and was the third president of the United States. Jefferson started designing Monticello when he was 14, after getting land from his father.

The property is near Charlottesville, Virginia, in the Piedmont area. It was originally about 5,000 acres (20 square kilometers). Enslaved black people worked on this large farm, growing tobacco and other crops. Later, Jefferson changed from tobacco to wheat farming.

Monticello is very important for its history and architecture. It is a National Historic Landmark. In 1987, Monticello and the nearby University of Virginia, which Jefferson also designed, became a UNESCO World Heritage Site. You can even see Monticello on the back of the United States nickel coin. It has been there almost every year since 1938.

Jefferson designed his home using ideas from neoclassical styles. He was inspired by an Italian architect named Andrea Palladio. Jefferson kept changing the design of his home throughout his time as president. He added many of his own ideas and popular European designs. The name Monticello means "little mountain" in Italian. It sits on top of an 850-foot (260-meter) high hill.

Near the main house was a path called Mulberry Row. This area had many smaller buildings for different jobs, like a nail factory. There were also homes for the enslaved people who worked in the house. Gardens for flowers, vegetables, and plant experiments were also part of the property. The homes for enslaved people who worked in the fields were further away.

Jefferson was buried on the grounds of Monticello in a place now called the Monticello Cemetery. This cemetery is owned by the Monticello Association, which is a group of his descendants. After Jefferson died, his daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph sold Monticello. In 1834, Uriah P. Levy, a U.S. Navy commodore, bought it and saved it from falling apart. He admired Jefferson and spent a lot of money to fix it up. His nephew, Jefferson Monroe Levy, took over in 1879 and also worked hard to restore it. In 1923, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation (TJF) bought Monticello. They now run it as a museum and educational center.

Contents

- Designing and Building Monticello

- Saving Monticello for the Future

- Inside Monticello: Decorations and Furniture

- Food and Cooking at Monticello

- Homes for Enslaved People on Mulberry Row

- Other Buildings and the Plantation

- Monticello's Architecture

- Monticello in Other Media

- Copies of Monticello

- Monticello's Legacy

- Images for kids

- See also

Designing and Building Monticello

Jefferson's home was built as a large farm house, which became a beautiful villa. Work on the first version of Monticello began in 1768. Jefferson moved into a small building on the property in 1770. His wife, Martha Wayles Skelton, joined him there in 1772. Many people, including enslaved individuals, worked on building and rebuilding his home.

After his wife passed away in 1782, Jefferson left Monticello in 1784. He went to France to serve as the United States Minister. While in Europe, he saw many classical buildings he had read about. He also discovered new French architectural styles. This trip likely inspired him to redesign his own home.

In 1794, after being the first U.S. Secretary of State, Jefferson started rebuilding Monticello. He used the ideas he had gathered in Europe. The remodeling continued through most of his time as president (1801–1809). Even though it was mostly finished by 1809, Jefferson kept working on Monticello until he died in 1826.

Jefferson made the house much larger by adding a central hallway and more rooms. He changed the second floor into a mezzanine bedroom area. The inside of the house has two main large rooms. One was an entrance hall and museum, where Jefferson showed off his scientific interests. The other was a music and sitting room.

The most striking new feature was an eight-sided dome. He put this dome above the west side of the building. A visitor once called the room inside the dome "a noble and beautiful apartment." However, it was not used very often. This might have been because it was too hot in summer and too cold in winter. Also, you could only reach it by climbing a steep, narrow staircase. Today, the dome room looks just as it did when Jefferson lived there. It has "Mars yellow" walls and a green and black checkered floor.

Summers in the Monticello area are very hot. Inside the house, temperatures could reach around 100°F (38°C). Jefferson was interested in old Roman ways of controlling temperature. He designed Monticello with a large central hall and windows that lined up. This allowed cool air to flow through the house. The dome also helped by drawing hot air up and out. Today, a mild air conditioning system is used to protect the house and its contents.

Before Jefferson died, Monticello started to look a bit worn down. He was very busy with his university project in Charlottesville. This, along with other challenges, took his attention away. The main reason for the house's condition was his growing debts. In his last years, many things at Monticello went without repair. A visitor in 1824 noted that the house was "rather old and going to decay."

Saving Monticello for the Future

After Jefferson passed away on July 4, 1826, his daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, inherited Monticello. However, the estate had many debts. Martha Randolph also had money problems in her own family. In 1831, she sold Monticello to a local pharmacist, James Turner Barclay, for $7,500.

In 1834, Barclay sold it for $2,500 to Uriah P. Levy. Levy was the first Jewish commodore in the U.S. Navy. He greatly admired Jefferson and used his own money to fix, restore, and save the house. During the American Civil War, the Confederate government took the house. They sold it to a Confederate officer. But Levy's family got the property back after the war.

Levy's family had disagreements over his estate. These issues were settled in 1879. Uriah Levy's nephew, Jefferson Monroe Levy, bought out the other family members for $10,050. He then took charge of Monticello. Like his uncle, Jefferson Levy paid for repairs and restoration. The house and grounds had become quite run down during the family's legal battles. Together, the Levy family saved Monticello for almost 100 years.

In 1909, Maud Littleton visited Monticello. After her visit, she started a campaign to have Monticello taken from Jefferson Levy. She used the press and tried to pass bills in Congress, but they failed. Littleton also tried to buy Monticello. Levy was upset by her actions and refused to sell. However, because of money problems, Levy eventually sold Monticello to a foundation.

In 1923, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, a private non-profit group, bought the house from Jefferson Levy for $500,000. They continued the restoration work. Since then, more restoration has been done at Monticello.

The Jefferson Foundation now runs Monticello as a house museum and learning center. Visitors can walk around the grounds and tour rooms on the lower floors. There are also special tours that let you see the second and third floors, including the famous dome room.

Monticello is a National Historic Landmark. It is the only private home in the United States that is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This designation also includes the original buildings of Jefferson's University of Virginia. Between 1989 and 1992, a team of architects made detailed drawings of Monticello. These drawings are kept at the Library of Congress.

Jefferson also designed other important buildings. These include Poplar Forest, his private getaway, and the "academic village" of the University of Virginia. He also designed the Virginia State Capitol in Richmond.

Inside Monticello: Decorations and Furniture

Many of the decorations inside Monticello show Jefferson's own ideas.

The main entrance is through the porch on the east side. The ceiling of this porch has a special plate connected to a weather vane. This shows the direction of the wind. A large clock on the outside wall only has an hour hand. Jefferson thought this was accurate enough for the enslaved people who worked there. This clock shows the same time as the "Great Clock" inside the entrance hall.

The entrance hall has copies of items collected by Lewis and Clark. Jefferson sent them on a trip across the country to explore the Louisiana Purchase. Jefferson had the floor painted "true grass green." An artist suggested this to make the house feel like the outdoors.

Jefferson's private rooms are in the south wing. His library holds many books from his third collection. His first library burned in a fire. He sold his second library in 1815 to the United States Congress. This was to replace books lost when Washington D.C. was burned during the War of 1812. This second library became the start of the Library of Congress.

Monticello might seem huge, but it has about 11,000 square feet (1,022 square meters) of living space. Jefferson thought a lot of furniture wasted space. So, the dining room table was only set up for meals. Beds were built into alcoves in thick walls, which also had storage space. Jefferson's bed could open to two sides: his study and his dressing room.

In 2017, a room believed to be Sally Hemings' living area was found next to Jefferson's bedroom. This was during an archaeological dig. It is being restored as part of the Mountaintop Project. This project aims to tell a more complete story of both enslaved and free families at Monticello.

The west side of the house looks like a smaller villa. Its lower floor is hidden in the hillside.

The north wing has two guest bedrooms and the dining room. It has a dumbwaiter built into the fireplace. There are also wheeled serving tables and a spinning door with shelves for serving food.

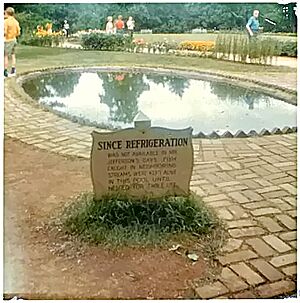

Food and Cooking at Monticello

Monticello is famous for helping to make macaroni and cheese popular in the United States. While it wasn't invented there, Jefferson's enslaved cook, James Hemings, made the dish well-known. He perfected it to be similar to how it is made today.

Homes for Enslaved People on Mulberry Row

Jefferson placed some of the homes for enslaved people on Mulberry Row. This was a 1,000-foot (300-meter) road with buildings for enslaved people, services, and workshops. Mulberry Row was about 300 feet (90 meters) south of the main house. The homes faced the Jefferson mansion. These cabins were for enslaved people who worked in the mansion or in Jefferson's businesses. They were not for those who worked in the fields.

Archaeological studies show that the rooms in these cabins were larger in the 1770s than in the 1790s. Researchers are still discussing what this means. Earlier homes for enslaved people had two rooms, with one family per room and a shared door. But from the 1790s, each room or family had its own door. Most cabins were single-room buildings.

By the time Jefferson died, some enslaved families had lived and worked at Monticello for four generations. Thomas Jefferson kept records of how children worked on his farm. Until age 10, children helped as nurses. When tobacco was grown, children were a good height to remove tobacco worms from the plants. When wheat became the main crop, fewer people were needed for farming. So, Jefferson started teaching trades. He said children would "go into the ground or learn trades." Girls started spinning and weaving cloth at age 16. Boys made nails from age 10 to 16. In 1794, a dozen boys worked in the nail factory. Boys working there received more food and sometimes new clothes if they did well. After the nailery, boys became blacksmiths, barrel makers, carpenters, or house servants.

Six families and their descendants were featured in an exhibit called Slavery at Jefferson's Monticello: Paradox of Liberty. This exhibit was at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History from January to October 2012. It also looked at Jefferson as an enslaver. This was the first exhibit on the national mall to discuss these topics.

In February 2012, Monticello opened a new outdoor exhibit called Landscape of Slavery: Mulberry Row at Monticello. This exhibit shares more about the lives of the hundreds of enslaved people who lived and worked on the plantation.

Other Buildings and the Plantation

The main house had smaller buildings to the north and south. Mulberry Row, a line of outbuildings and homes for enslaved people, was nearby to the south. These buildings included a dairy, washhouse, storage, a small nail factory, and a carpentry shop. A stone weaver's cottage still stands, as does the tall chimney of the carpentry shop. The foundations of other buildings can also be seen.

A cabin on Mulberry Row was once the home of Sally Hemings. She was Jefferson's sister-in-law and an enslaved woman who worked in the household. Many believe she had a long relationship with Jefferson and had six children with him. Four of these children lived to adulthood. Later, Hemings lived in a room below the main house.

On the hill below Mulberry Row, enslaved Africans took care of a large vegetable garden for the main house. Jefferson used the gardens of Monticello to grow flowers and food. He also experimented with different plant types. The house was the center of a 5,000-acre (20 square kilometer) plantation. About 150 enslaved people worked there.

Learning About Enslaved Lives

In recent years, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation has created programs to better understand the lives of enslaved people at Monticello. Starting in 1993, researchers interviewed descendants of Monticello slaves. This "Getting Word Project" collected oral histories. It gave new insights into the lives of enslaved people and their families. For example, it was found that no enslaved people took Jefferson as a last name. Many had their own last names as early as the 1700s.

Parts of Mulberry Row have been made into archeological sites. Digs and studies there are teaching us a lot about the lives of enslaved people on the plantation. In 2000–2001, the burial ground for enslaved Africans at Monticello was found. In 2001, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation held a ceremony for the burial ground. The names of known enslaved people from Monticello were read aloud. More archaeological work is helping us learn about African American burial customs.

In 2003, Monticello hosted a reunion of Jefferson's descendants. This included families from both the Wayles's and Hemings's sides. The descendants organized this event and formed a new group called the Monticello Community. More reunions have been held since then.

Buying More Land

In 2004, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation bought Mountaintop Farm. This was the only property that overlooked Monticello. Jefferson had called this taller mountain Montalto. The foundation spent $15 million to buy the property. This was to stop new homes from being built there. Jefferson had owned it as part of his plantation, but it was sold after his death. In the 1900s, its farmhouses were divided into apartments for many University of Virginia students. The foundation had long wanted to buy this property when it became available.

Monticello's Architecture

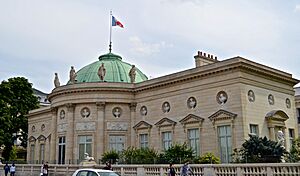

In 1784, Thomas Jefferson traveled in France. This trip greatly influenced his ideas about architecture. He was especially inspired by the neoclassical style common in French buildings. This is why Monticello is designed in a classical revival style.

Jefferson was also interested in the Pantheon in Rome. Even though he never saw it in person, its design influenced Monticello. It also inspired the Rotunda, a library at the University of Virginia. Both buildings have a temple-like front with large columns, similar to the Pantheon. The back of the buildings also honors the Roman temple by including a dome shape.

After Jefferson left Washington's cabinet, he decided to remodel parts of Monticello. At this time, he was very much influenced by the Hôtel de Salm in Paris. The house also looks similar to Chiswick House, a neoclassical house in London built in the 1720s. Chiswick House was also inspired by the architect Andrea Palladio.

Monticello in Other Media

Monticello was shown in Bob Vila's TV show, Guide to Historic Homes of America. The tour included the Honeymoon Cottage and the Dome Room. The Dome Room is open to the public for a limited number of tours each year.

Copies of Monticello

In 2014, S. Prestley Blake built a 10,000-square-foot (930-square-meter) copy of Monticello in Somers, Connecticut. You can see it on Route 186. In 2019, Blake gave the house to Hillsdale College. It now serves as a campus for their Blake Center for Faith and Freedom.

The entrance of the Naval Academy Jewish Chapel in Annapolis is also designed like Monticello.

Chamberlin Hall at Wilbraham & Monson Academy in Wilbraham, Massachusetts, was built in 1962. It is modeled after Monticello and houses the Academy's Middle School.

In August 2015, Dallas Baptist University built one of the largest copies of Monticello. It includes its entry halls and a dome room. This building is about 23,000 square feet (2,137 square meters). It is home to the Gary Cook School of Leadership and the University Chancellor's offices.

Saint Paul's Baptist Church in Richmond is also modeled after Monticello.

Pi Kappa Alpha's Memorial Headquarters, opened in 1988, was inspired by Monticello's architecture. It is located in Memphis, Tennessee.

Perrot Library (1931) in Old Greenwich, Connecticut, was inspired by Jeffersonian architecture and Monticello.

The outside of University of the Cumberlands' Ward and Regina Correll Science Complex also copies Thomas Jefferson's Monticello mansion. This $1 million expansion started in May 2007, and classes began in January 2009.

Monticello's Legacy

Monticello's image has appeared on U.S. money and postage stamps. A picture of the west side of Monticello has been on the back of the nickel since 1938. There was a short break in 2004 and 2005 for other designs. Monticello was also the title for the 2015 play Jefferson's Garden, which was about Jefferson's life.

Monticello also appeared on the back of the two-dollar bill from 1928 to 1966. The bill was brought back in 1976. It still has Jefferson's picture on the front. But Monticello on the back was replaced with a picture of John Trumbull's 1818 painting Declaration of Independence. The gift shop at Monticello often gives out two-dollar bills as change.

The 1994 special Thomas Jefferson 250th Anniversary silver dollar also features Monticello on its back.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Monticello (Virginia) para niños

In Spanish: Monticello (Virginia) para niños

- Bibliography of Thomas Jefferson

- Jeffersonian architecture

- List of residences of presidents of the United States

- List of burial places of presidents and vice presidents of the United States

- History of early modern period domes

- People from Monticello

- Presidential memorials in the United States

- Thomas Jefferson Center for Historic Plants

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |