American Colonization Society facts for kids

The American Colonization Society (ACS), also known as the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America until 1837, was started in 1816 by Robert Finley. Its main goal was to help and encourage free Black people in the United States to move to Africa.

The ACS was created because many people in the United States wondered what to do about the growing number of free Black people. After the American Revolutionary War, the number of free Black people grew a lot, from 60,000 in 1790 to 300,000 by 1830.

Some slave owners worried that free Black people might help enslaved people escape or start rebellions. Also, many white Americans at the time believed that African Americans were not equal. They thought Black people should move to a place where they could live peacefully, without unfair treatment, and be full citizens.

However, most African Americans and people who wanted to end slavery (abolitionists) were strongly against this plan. Many Black families had lived in the United States for generations. They felt they were no more African than white Americans were European. The ACS claimed that Black people moved voluntarily, but many, both free and enslaved, were pressured to leave. Sometimes, slave owners would only free their slaves if they agreed to leave the country right away.

Historian Marc Leepson said that "Colonization proved to be a giant failure." It did not stop the problems that led to the American Civil War. Between 1821 and 1847, only a few thousand African Americans moved to what would become Liberia. This was a very small number compared to the millions of Black people in the U.S. By 1833, the Society had sent 2,769 people to Liberia, while the Black population in the U.S. grew by about 500,000 in the same years. Sadly, almost half of those who moved to Africa died from tropical diseases. Also, sending people and supplies to Africa was very expensive.

By the 1830s, the ACS faced strong opposition from white abolitionists. Leaders like Gerrit Smith and William Lloyd Garrison spoke out against it. Garrison wrote a book called Thoughts on African Colonization (1832). He said the Society was a "fraud." He and his followers believed the ACS was not solving the problem of slavery. Instead, they thought it was actually helping to keep slavery going by removing free Black people who might challenge the system.

Contents

Why the Society Started

Slavery Grows in the South

After the cotton gin was invented in the 1790s, growing and selling cotton became very profitable. Large farms called plantations, worked by enslaved people, were central to this business. The demand for enslaved people grew. Even after importing slaves from Africa became illegal in 1808, enslaved people were still sold within the U.S. Many enslaved people were forcibly moved from states like Maryland and Virginia to the Deep South. By the mid-1800s, about four million enslaved people lived in the U.S.

More Free Black People

More and more Black people became free during this time. This was partly because of new ideas about freedom from the American Revolution. Also, some religious leaders and abolitionists helped enslaved people gain their freedom. Even in the North, where slavery was slowly ending, free Black people often faced unfair treatment and laws that limited their rights. The U.S. government did not do much to change this. Many white people in the North also saw free Black people as unwelcome, fearing they would take jobs.

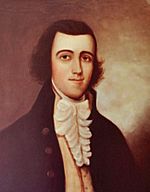

Some slave owners started to support the idea of sending free Black people away after a planned slave uprising led by Gabriel Prosser in 1800. They also worried about the fast growth in the number of free African Americans after the Revolutionary War. From 1790 to 1810, the number of free Black people increased from about 59,000 to over 186,000. Slaveholders feared that free Black people could cause problems for their slave-based society.

Early Efforts to Send People to Africa

In 1786, a British group tried to create a colony in West Africa called Sierra Leone. This was a place for poor Black people from London. The British government also supported this idea, offering to move Black Loyalists (who had fought for the British in the American Revolution) from Nova Scotia, where they faced harsh weather and discrimination. Later, people from Jamaica and former slaves freed by the British Navy were also sent there.

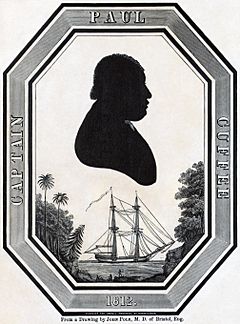

Paul Cuffe's Work

Paul Cuffe (1759–1817) was a successful ship owner and activist. He was a Quaker and had both African and Native American heritage. He believed in settling freed American slaves in Africa. He got support from the British government, Black leaders in the U.S., and members of Congress. In 1815, he paid for a trip himself. The next year, Cuffe took 38 American Black people to Freetown, Sierra Leone. He died in 1817, but his work helped set the stage for the American Colonization Society.

Other Ideas for Relocation

There were other ideas for where to send former slaves, though none of them worked out. Some people suggested settling them in the new Western territories gained from the Louisiana Purchase, or on the Pacific coast. This would be like creating a Black reservation. Haiti was also an option, and there was an attempt to create a farming community of former American slaves on an island in Haiti called Île-à-Vache. Even Abraham Lincoln had a plan to settle them in what is now Panama.

Beginning of the ACS

How it Started

The ACS began in 1816. Charles F. Mercer, a politician from Virginia, found old records about debates on sending Black people away after Gabriel Prosser's rebellion. Mercer pushed for the state to support this idea. He contacted Robert Finley, a Presbyterian minister, who liked the plan.

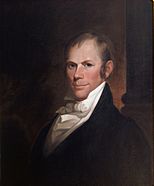

On December 21, 1816, the Society was officially formed in Washington, D.C. Many important people supported it, including Henry Clay, John Randolph, and Bushrod Washington. Even U.S. Presidents like Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and James Madison were supporters. Madison was the Society's president in the early 1830s.

At the first meeting, Reverend Finley suggested creating a colony in Africa for free Black people. He wanted to send them "with their consent" to Africa or another suitable place. The organization opened branches across the United States, especially in Southern states. It played a key role in creating the colony of Liberia.

The ACS was supported by groups who usually disagreed about slavery. Slave owners, for example, thought sending free Black people away would help prevent slave rebellions. They also believed it would make their enslaved people more valuable. On the other hand, a group of religious people, Quakers, and abolitionists supported the ACS because they wanted to end slavery. They believed Black people would have a better chance at freedom in Africa than in the U.S., where they faced discrimination. These two very different groups found common ground in supporting the idea of "repatriation" (sending people back to their homeland).

Leaders of the ACS

The presidents of the ACS were often from the Southern United States. The first president was Bushrod Washington, who was the nephew of President George Washington. From 1836 to 1849, Henry Clay, a politician and slaveholder from Kentucky, was president. John H. B. Latrobe led the ACS from 1853 until he died in 1891.

What the ACS Hoped to Achieve

The colonization project had chapters in every state and aimed for three main things. First, it wanted to provide a place where former slaves, freed people, and their children could live freely without racism. Second, it wanted to make sure the colony had what it needed to succeed, like good land for farming. Third, it aimed to stop the Atlantic slave trade by watching ship traffic along the coast. Some, like Presbyterian clergyman Lyman Beecher, also hoped to spread Christianity in Africa.

How They Raised Money

The Society raised money by selling memberships. Its members also asked Congress and the President for support. In 1819, they received $100,000 from Congress. On February 6, 1820, the first ship, the Elizabeth, sailed from New York to West Africa. It carried three white ACS agents and 88 African-American people who were moving. The ways of choosing people and paying for their travel to Africa varied by state.

People Against Colonization

At first, many people thought colonization was a good idea. It was seen as a way to solve the problems of slavery and help free Black people. Judge James Hall, a magazine editor, wrote in 1834 that it was "one of the noblest devices" that brought together Christians and politicians for a common goal.

Black Opposition

However, from the very beginning, most Black Americans strongly disliked the Society. Black activist James Forten said in 1817, "we have no wish to separate from our present homes." As soon as they heard about the ACS, 3,000 Black people gathered in a church in Philadelphia and strongly spoke out against it.

They felt it was wrong to talk about their "consent" to leave when the Society was formed without their input. They also felt pressured to leave. Frederick Douglass spoke against colonization, saying, "We live here—have lived here—have a right to live here, and mean to live here." Martin Delany called Liberia a "miserable mockery" and a "racist scheme" to get rid of free Black people. He suggested Central and South America as better places for Black Americans to settle.

Many African Americans saw colonization as a way to deny them their rights as citizens and to strengthen slavery. They started to remove "African" from the names of their organizations and used "The Colored American" instead.

Sometimes, the Society even made conditions worse for Black people in the U.S. to encourage them to leave. For example, the Society helped bring back strict laws in Ohio that forced many free Black people out of Cincinnati. In 1832, a meeting in Cincinnati passed resolutions stating that Black people had a right to freedom and equality in their birth country, the U.S. They felt they should decide where they lived. They suggested Canada or Mexico if Black people wanted to leave, as these places offered civil rights and a similar climate. They also questioned the motives of ACS members who claimed to be Christian but did not try to improve conditions for Black people in the U.S.

White Opposition

William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison started his anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator, in 1831. In 1832, he published Thoughts on African Colonization. President Lincoln later said that Garrison's ideas helped put an end to slavery on the country's political agenda.

Garrison had initially supported the ACS. However, he later strongly opposed it. He believed the Society's main goal was not to end slavery, but to remove free Black people from America. This would prevent slave rebellions. He also pointed out that colonization had made enemies of the native people in Africa. Both he and Gerrit Smith were upset when they learned that alcohol was being sold in Liberia. Garrison also questioned sending African Americans to such an unhealthy place. He argued that the ACS actually slowed down the freeing of slaves.

Garrison also pointed out that Black people were born in America and had just as much right to be there as white people. He believed that if the Society truly cared about Black people's happiness, they should work to improve their lives in America, not send them away.

Gerrit Smith

The kind and generous person Gerrit Smith had been a major supporter of the ACS. However, his support turned into strong opposition in the early 1830s. He realized that the Society was "quite as much an Anti-Abolition, as Colonization Society." He felt it had become a tool to support slavery, not end it.

In November 1835, he sent a final check to the Society and said he would not give any more money. He explained that the Society was more interested in fighting against the anti-slavery movement than in building its colony. He felt that being a member of the Colonization Society and an abolitionist at the same time was a contradiction.

The Colony of Liberia

In 1821, Lt. Robert F. Stockton used force to persuade a local leader named King Peter to sell land for an American colony. This land became Cape Montserrado, and the settlement was named Monrovia. Later, Jehudi Ashmun, Stockton's replacement, continued to buy or lease tribal lands along the coast and rivers in Africa. In May 1825, King Peter and other local kings agreed to a treaty with Ashmun. In exchange for land, the native people received items like rum, gunpowder, umbrellas, shoes, and tobacco.

Between 1820 and 1843, 4,571 people moved to Liberia. However, by 1843, only 1,819 of them (40%) were still alive. The ACS knew about the high death rate but kept sending more people.

It's too simple to say that the American Colonization Society alone founded Liberia. Much of what became Liberia was a group of settlements sponsored by different state colonization societies. Examples include Mississippi-in-Africa, Kentucky in Africa, and the Republic of Maryland. The Republic of Maryland was quite developed, with its own laws and flag. These separate colonies eventually joined together to form Liberia, but this process was not finished until 1857.

Civil War and Freedom

Since the 1840s, Abraham Lincoln had admired Henry Clay and supported the ACS's idea of sending Black people to Liberia. Early in his presidency, Lincoln tried several times to arrange for Black people to move, but these plans failed.

The ACS continued its work during the American Civil War. It sent 168 Black people to Liberia during the war. After the war, it sent 2,492 more people of African descent to Liberia in five years. The U.S. government gave some support for these efforts through the Freedmen's Bureau.

Some historians believe Lincoln stopped supporting colonization by 1863, especially after Black soldiers joined the fight. His biographer, Stephen B. Oates, said Lincoln thought it was wrong to ask Black soldiers to fight for the U.S. and then send them away. Others believe Lincoln still hoped for colonization as late as 1864.

However, by the end of his first term as president, Lincoln publicly gave up on the idea of colonization after talking with Frederick Douglass, who strongly opposed it. On April 11, 1865, as the war was ending, Lincoln gave a speech supporting the right to vote for Black people. This speech led to his assassination by John Wilkes Booth, who was against freedom and voting rights for Black people.

End of the Society

Colonization was very expensive. Under Henry Clay's leadership, the ACS tried for many years to get the U.S. Congress to pay for people to move, but they were not successful. The ACS did get some money from state governments in the 1850s, like Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. In 1850, Virginia set aside $30,000 each year for five years to help with emigration. However, the money the ACS collected was not enough to meet its goals. The Society "had never obtained the confidence of the American people."

The movement never became very successful for three main reasons:

- Free Black people were not interested in leaving.

- Some abolitionists were against it.

- The cost and scale of moving so many people were too great. There were millions of Black enslaved people in the U.S., but colonization only moved a few thousand free Black people.

After World War I began, the ACS warned Liberia's President Daniel Howard that getting involved in the war could threaten Liberia's land.

In 1913, and again when it officially closed in 1964, the Society gave its records to the U.S. Library of Congress. These records contain a lot of information about the Society's founding, its role in creating Liberia, how it managed the colony, how it raised money, how it recruited settlers, and how Black settlers built their new nation.

In Liberia, the Society had offices in Monrovia. These offices closed in 1956 when the government tore down buildings to construct new public ones. However, the land officially belonged to the Society into the 1980s, and it owed a lot of unpaid property taxes because the government couldn't find an address to send the bills.

How Views on the ACS Changed

In the 1950s, racism became a more important topic. By the late 1960s and 1970s, the Civil Rights Movement brought racism to the forefront of public attention. This led historians to look at the ACS's reasons more closely, focusing on racism rather than just its stance on slavery. By the 1980s and 1990s, some historians even described the Society as an organization that supported slavery. More recently, some scholars have stopped calling the ACS a pro-slavery group and have started to see it as an anti-slavery organization again.

|

See also

In Spanish: American Colonization Society para niños

In Spanish: American Colonization Society para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |