Frederick Douglass facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Frederick Douglass

|

|

|---|---|

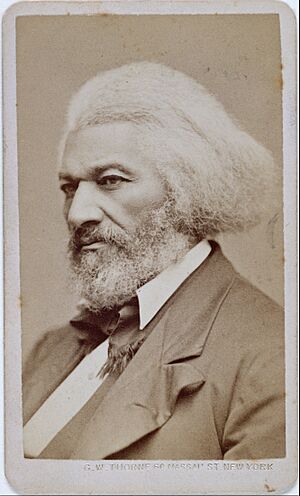

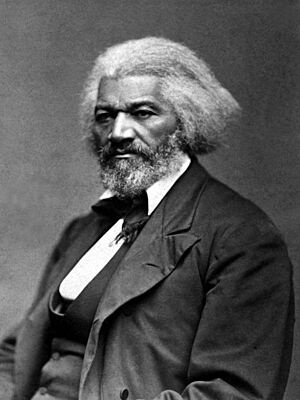

Douglass, c. 1879

|

|

| United States Minister Resident to Haiti | |

| In office November 14, 1889 – July 30, 1891 |

|

| Appointed by | Benjamin Harrison |

| Preceded by | John E. W. Thompson |

| Succeeded by | John S. Durham |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey

c. February 14, 1818 Cordova, Maryland, U.S. |

| Died | February 20, 1895 (aged 77–78) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

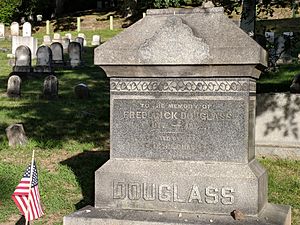

| Resting place | Mount Hope Cemetery, Rochester, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses |

|

| Relatives | Douglass family |

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

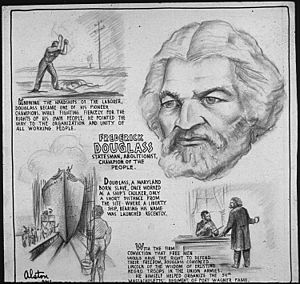

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, around February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an important American leader. He fought for big changes in society. He was a leading abolitionist, meaning he wanted to end slavery. He was also a powerful speaker, a talented writer, and a respected government official. In the 1800s, he became the most important leader in the fight for African-American civil rights.

After escaping from slavery in Maryland in 1838, Douglass became a famous leader. He was known for his amazing speeches and clear writings against slavery. Many people who supported slavery said enslaved people were not smart enough to be free. Douglass, with his intelligence, proved them wrong. People in the North sometimes found it hard to believe he had once been enslaved. So, Douglass wrote his first autobiography to share his true story.

Douglass wrote three autobiographies. His first, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), described his life as an enslaved person. It became a bestseller and helped people support the fight against slavery. His second book was My Bondage and My Freedom (1855). After the Civil War, Douglass kept fighting for the rights of formerly enslaved people. He wrote his last autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, in 1881, updated in 1892. Douglass also strongly supported women's suffrage (the right for women to vote). He held several government jobs.

Douglass believed in talking and working with people, even if they had different ideas. He thought the U.S. Constitution could be used to fight slavery. Some abolitionists criticized him for being willing to talk with slave owners. He famously said, "I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong."

Contents

Early Life and Escaping Slavery

Born into Slavery

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born into slavery in Talbot County, Maryland. He was likely born in his grandmother's cabin. Douglass did not know his exact birth date. He later guessed he was born in 1817. However, records from his former owner suggest he was born in February 1818. He chose to celebrate February 14 as his birthday. This was because his mother called him her "Little Valentine."

His Family

Douglass's mother, Harriet Bailey, was of African descent. His father was a white man, possibly his master. Douglass wrote, "My father was a white man." He never found out his father's name. Douglass was also likely part Native American. His mother named him Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey. After he escaped in 1838, he changed his last name to Douglass.

He wrote about being separated from his mother when he was a baby. This was a common practice for enslaved children. His mother lived about 12 mi (19 km) away. She visited him only a few times before she died when he was seven. Young Frederick lived with his enslaved grandmother, Betsy Bailey. His grandfather, Isaac, was free.

Learning to Read and Write

The Auld Family's Influence

When Frederick was six, he was sent to the Wye House plantation. Later, he was given to Lucretia Auld. She sent him to live with Hugh Auld and his wife Sophia in Baltimore. Sophia Auld was kind to Frederick at first. She made sure he had enough food and clothes. Douglass said she treated him like a human being. He felt lucky to be in the city. Enslaved people had a bit more freedom there than on plantations.

When Frederick was about 12, Sophia Auld started teaching him the alphabet. But Hugh Auld strongly disagreed. He believed that if enslaved people learned to read, they would want freedom. Douglass later said this was the "first decidedly antislavery lecture" he had ever heard. He realized that learning was his path to freedom.

Sophia stopped teaching Frederick. She tried to keep all reading materials away from him. But Frederick was determined. He secretly taught himself to read and write. He got help from white children in his neighborhood. He also studied writings he found. He often said, "knowledge is the pathway from slavery to freedom." Reading made him hate slavery. He learned his mother had also been able to read.

Life on Other Plantations

When Douglass was hired out to William Freeland, he started a secret Sunday school. There, he taught more than thirty enslaved men to read.

In 1833, Frederick's owner, Thomas Auld, sent him to work for Edward Covey. Covey was known for "breaking" the spirit of enslaved people. Covey whipped Frederick often and cruelly. The constant beatings almost broke his spirit. However, when Frederick was 16, he fought back against Covey. After Douglass won the fight, Covey never tried to beat him again. Douglass saw this fight as a turning point. He said, "You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man."

Escape to Freedom

Douglass first tried to escape from Freeland but failed. In 1837, he met Anna Murray. She was a free black woman in Baltimore. Anna was about five years older than him. Her freedom inspired him. Anna encouraged him and helped him with money for his escape.

On September 3, 1838, Douglass successfully escaped. He boarded a northbound train in Baltimore. He was dressed in a sailor's uniform that Anna Murray had given him. She also gave him some of her savings. He carried identification papers from a free Black sailor.

Douglass traveled through Havre de Grace, Maryland, then by train to Wilmington, Delaware. From there, he took a steamboat to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This city was known for its anti-slavery views. He then went to New York City. Abolitionist David Ruggles helped him there. His journey to freedom took less than 24 hours. Douglass wrote about arriving in New York:

I have often been asked, how I felt when first I found myself on free soil. ... A new world had opened upon me. ... I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life. It was a time of joyous excitement... I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions.

Once in New York, Douglass sent for Anna Murray. They married on September 15, 1838. They used the last name Johnson at first to avoid being caught.

Religious Beliefs

As a child, Douglass heard religious sermons. Sophia Auld sometimes read the Bible to him. He wanted to read the Bible himself and eventually became a Christian. He was guided by Rev. Charles Lawson, a Black man.

Douglass often used Bible stories in his speeches. Even though he was a believer, he strongly criticized religious people who supported slavery. He said that slaveholders who claimed to be Christian were being hypocrites. He believed that ministers who defended slavery were the worst kind of sinners.

In his famous speech, "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?", he criticized religious leaders who stayed silent about slavery. He said they committed a "blasphemy" (showing disrespect for God) by teaching that slavery was approved by religion. He praised ministers who spoke out against slavery. He asked religious groups to fight against slavery.

During his visits to the United Kingdom, Douglass asked British Christians not to support American churches that allowed slavery. When he returned to the U.S., he started a newspaper called the North Star. Its motto was "Right is of no sex, Truth is of no color, God is the Father of us all, and we are all Brethren." Douglass remained a deeply spiritual man.

Family Life

Douglass and Anna Murray had five children: Rosetta, Lewis Henry, Frederick Jr., Charles Remond, and Annie. Annie died at age ten. Charles and Rosetta helped him with his newspapers.

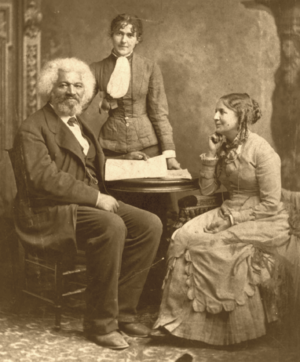

Anna Douglass supported her husband's public work. Anna died in 1882. In 1884, Douglass married Helen Pitts. She was a white suffragist (someone who fights for voting rights) and abolitionist. Pitts was the daughter of one of Douglass's abolitionist friends. She had worked as his secretary.

This marriage caused a lot of discussion because Pitts was white and nearly 20 years younger than Douglass. Many people in her family stopped speaking to her. His children felt it disrespected their mother. However, feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton congratulated them. Douglass said that his first marriage was to someone the color of his mother, and his second was to someone the color of his father.

Fighting for Freedom and Rights

Becoming an Abolitionist Speaker

Frederick and Anna Douglass settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts, in 1838. They later moved to Lynn, Massachusetts, in 1841. They adopted the last name Douglass.

Douglass joined the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, a Black church. He became a licensed preacher in 1839. This helped him develop his speaking skills. He went to abolitionist meetings. He read William Lloyd Garrison's newspaper, The Liberator. Garrison greatly influenced him.

In 1841, Douglass was asked to speak at an anti-slavery meeting. He told his story with such power that he was asked to become a full-time anti-slavery lecturer. He was only 23.

In September 1841, Douglass and his friend James N. Buffum were forced off a train in Lynn. They refused to sit in the separate coach for Black people. This was an early protest against unfair treatment.

In 1843, Douglass toured the Eastern and Midwestern U.S. with the American Anti-Slavery Society. He often faced angry crowds. In Pendleton, Indiana, he was attacked and his hand was broken. It never healed properly.

His Autobiographies

Douglass's most famous work is his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. It was published in 1845. Some people doubted that a Black man could write so well. The book was a bestseller. It was reprinted nine times in three years. It was also translated into French and Dutch. It greatly helped the abolitionist cause.

He published two more autobiographies: My Bondage and My Freedom (1855) and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881, revised 1892).

Travels to Europe

Friends worried that his fame would lead his former owner to try and recapture him. So, in 1845, Douglass traveled to Ireland and Great Britain. This was during the Great Famine in Ireland.

Douglass was amazed by the freedom from racism he experienced:

Eleven days and a half gone, and I have crossed three thousand miles of the perilous deep. ... I breathe, and lo! the chattel [slave] becomes a man. I gaze around in vain for one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as his slave, or offer me an insult. ... I find myself regarded and treated at every turn with the kindness and deference paid to white people.

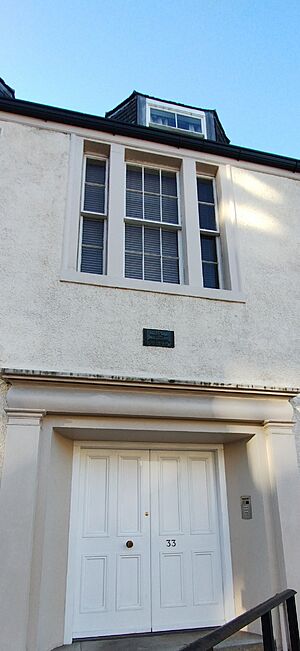

He gave many lectures for two years. In 1846, British supporters raised money to buy his freedom from Thomas Auld. Douglass became legally free. He returned to America in 1847. Plaques in Cork, Waterford, London, and Edinburgh now mark his visit.

Starting a Newspaper and Helping the Underground Railroad

Back in the U.S. in 1847, Douglass started his first abolitionist newspaper. It was called the North Star. It was in Rochester, New York. Its motto was "Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren." He and his wife also helped over four hundred enslaved people escape through the Underground Railroad.

Douglass soon disagreed with William Lloyd Garrison. Garrison believed the Constitution supported slavery. Douglass came to believe the Constitution could be used to fight slavery. This disagreement caused a split in the abolitionist movement. Douglass argued that ending the Union would actually give slave states more control over slavery.

In 1848, ten years after his escape, Douglass wrote an open letter to his former master, Thomas Auld. He criticized Auld's cruelty. He also asked about family members still enslaved by him. He powerfully described the horrors of slavery. Yet, he ended by saying he felt no personal hatred. He offered Auld safety and comfort in his own home.

Fighting for Women's Rights

In 1848, Douglass was the only Black person at the Seneca Falls Convention. This was the first women's rights convention. Many people there did not want to support a resolution for women's suffrage (women's right to vote). Douglass spoke strongly in its favor. He said he could not accept the right to vote as a Black man if women could not also have that right. His words helped the resolution pass.

In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world.

After the Civil War, the 15th Amendment was proposed. It would give Black men the right to vote. Douglass disagreed with some women's rights leaders like Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Stanton opposed the amendment because it did not include women. Douglass supported it. He believed it was a very important step. He thought linking it with women's suffrage at that time might cause both to fail. He told women he still supported their right to vote.

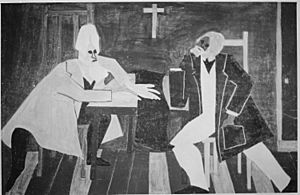

Meeting John Brown

Douglass met with the radical abolitionist John Brown several times. Brown stayed at Douglass's home for two weeks. This was before Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry. Brown tried to start a slave rebellion. Douglass met Brown secretly before the raid but decided not to join. Shields Green, an escaped slave staying with Douglass, chose to go with Brown.

After the raid in October 1859, Douglass was accused of being involved. He fled to Canada and then to England to avoid arrest. His youngest daughter, Annie, died while he was away. He returned to the U.S. the next year.

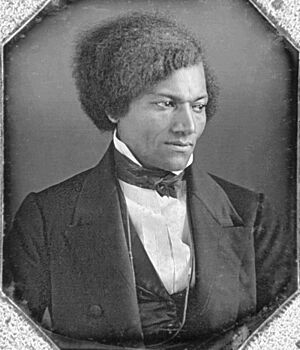

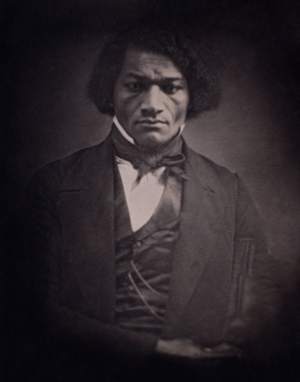

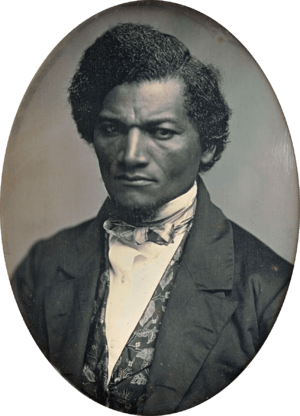

Using Photography for Change

Douglass understood the power of photography. He believed it could help end slavery and racism. This was because cameras showed the truth. He was the most photographed American of the 19th century. He used photos to share his political views. He rarely smiled in photos. He usually looked directly at the camera with a serious expression.

Civil War and Beyond

Fighting for Black Soldiers

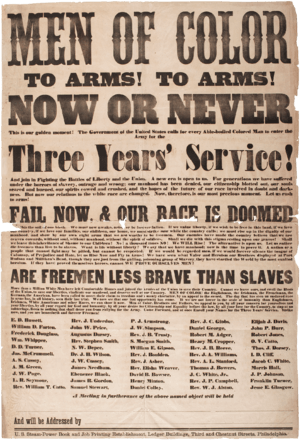

During the Civil War, Douglass argued that African Americans should be allowed to fight for their own freedom. When President Abraham Lincoln finally allowed Black soldiers to join the Union army, Douglass helped recruit them. His famous poster read Men of Color to Arms!. His sons, Charles and Lewis, served in the army.

Douglass met with President Lincoln in 1863. They discussed how Black soldiers were treated. They also talked about plans for freed slaves. Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, declared slaves in Confederate territory free. Douglass described the hope and excitement of that moment.

After the War

After the war, the 13th Amendment (1865) officially ended slavery. The 14th Amendment gave citizenship and equal protection under the law. The 15th Amendment protected voting rights regardless of race. Douglass met with President Andrew Johnson to discuss voting rights for Black people.

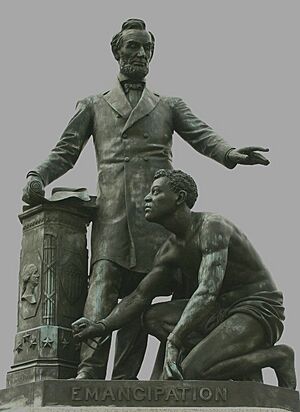

On April 14, 1876, Douglass gave a powerful speech at the unveiling of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington, D.C. He spoke honestly about Lincoln. He called him "the white man's President" but also recognized his role in ending slavery. He criticized the statue's design. He said the Black figure should be shown standing "erect on his feet like a man," not kneeling.

Later Years and Legacy

After the Civil War, Douglass continued to work for equality. He served as president of the Freedman's Savings Bank. However, violent groups like the Ku Klux Klan rose in the South. They tried to bring back white supremacy and take away rights from African Americans.

Douglass supported President Ulysses S. Grant in 1868. In 1870, he started his last newspaper, the New National Era. Grant used federal power to fight the Klan, which Douglass praised.

In 1872, his home in Rochester burned down. He then moved to Washington, D.C.

Douglass kept speaking about the importance of work, voting rights, and education. He pushed for school desegregation (ending separate schools for different races). In an 1869 speech, he defended Chinese immigration and their rights as citizens.

Frederick Douglass's Home

In 1877, Frederick Douglass bought a house in Washington, D.C. It had a large yard and a studio. He lived there from 1878 until he died in 1895. It is now known as the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

In 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Douglass as United States Marshal for the District of Columbia. He was the first person of color in that role. Later that year, Douglass visited his former enslaver, Thomas Auld, who was dying. The two men made peace. Douglass also bought his final home in Washington, D.C., which he named Cedar Hill.

In 1881, Douglass published the final version of his autobiography, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. He was also appointed Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia. His wife Anna died in 1882. He remarried Helen Pitts in 1884.

Douglass continued to travel and speak. He and Helen toured Europe and Egypt from 1886 to 1887.

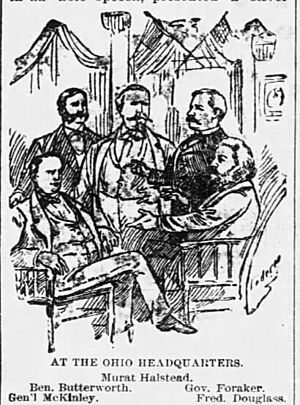

At the 1888 Republican National Convention, Douglass became the first African American to receive a vote for President in a major party's roll call. President Benjamin Harrison appointed him as U.S. minister to Haiti in 1889. But Douglass resigned in 1891 because he disagreed with U.S. policy towards Haiti.

Douglass did not support movements for Black people to leave the South or go back to Africa. He urged African Americans to stay and fight for their rights in the U.S. Speaking in Baltimore in 1894, he said, "I hope and trust all will come out right in the end, but the immediate future looks dark and troubled."

Death

On February 20, 1895, Frederick Douglass attended a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. He received a standing ovation. Shortly after returning home, he died of a heart attack at age 77.

His funeral was held at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church. Thousands of people paid their respects. His coffin was taken to Rochester, New York, where he had lived for 25 years. He was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery next to his first wife, Anna. His second wife, Helen, was later buried there too. His grave is one of the most visited in the cemetery.

His Writings and Speeches

Books and Newspapers

- 1845. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself (his first autobiography).

- 1853. "The Heroic Slave." A short story.

- 1855. My Bondage and My Freedom (his second autobiography).

- 1881 (revised 1892). Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (his third and final autobiography).

- 1847–1851. The North Star, an anti-slavery newspaper he started and edited.

- Many collections of his writings and speeches have been published.

Famous Speeches

- 1841. "The Church and Prejudice"

- 1852. "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?" (A very famous speech questioning what Independence Day meant to enslaved people)

- 1859. Self-Made Men.

- 1863, July 6. "Speech at National Hall, for the Promotion of Colored Enlistments."

- 1869. "Our Composite Nationality"

- 1881. John Brown: An Address by Frederick Douglass

Legacy and Honors

Frederick Douglass is remembered as a key figure in American history. He fought tirelessly to end slavery and for equal rights for all people. His advice to a young Black man near the end of his life was: ″Agitate! Agitate! Agitate!″ (meaning to speak up and push for change).

Many places and honors are named after him:

- The Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge in Washington, D.C.

- The Frederick Douglass National Historic Site (his home, Cedar Hill).

- Many schools across the country.

- In 1965, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp honoring him.

- Yale University created the Frederick Douglass Book Prize for books on slavery and abolition.

- In 2013, a statue of Douglass was unveiled in the United States Capitol Visitor Center.

- In 2017, the U.S. Mint issued a quarter featuring Frederick Douglass and his historic site.

- The Frederick Douglass Greater Rochester International Airport in Rochester, New York.

See also

In Spanish: Frederick Douglass para niños

In Spanish: Frederick Douglass para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |