Jacob Lawrence facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jacob Lawrence

|

|

|---|---|

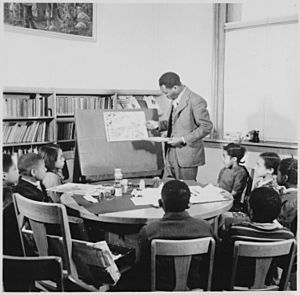

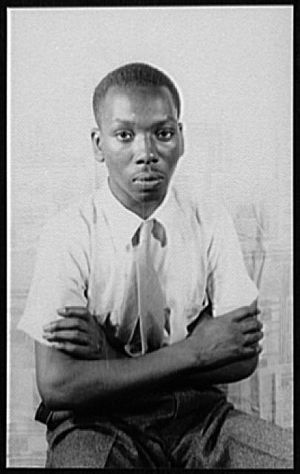

Lawrence in 1941

|

|

| Born | September 7, 1917 Atlantic City, New Jersey, United States

|

| Died | June 9, 2000 (aged 82) Seattle, Washington, United States

|

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Harlem Community Art Center |

| Known for | Paintings portraying African-American life |

|

Notable work

|

The Migration Series |

| Spouse(s) | |

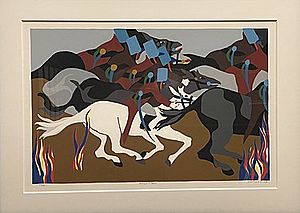

Jacob Lawrence was a famous American painter. He is known for his colorful and dynamic paintings that tell stories about African-American history and everyday life. He called his unique style "dynamic cubism." Lawrence used bright colors and strong shapes to show the experiences of Black people in America. He also taught art for many years at the University of Washington.

When he was only 23, Lawrence became nationally recognized for his amazing 60-panel series called The Migration Series. This series showed the Great Migration, which was when many African Americans moved from the southern United States to northern cities. His paintings are now in many famous museums around the world, like the Museum of Modern Art in New York. One of his paintings, The Builders, even hangs in the White House!

Contents

Biography

Early years

Jacob Lawrence was born on September 7, 1917, in Atlantic City, New Jersey. His parents had moved there from the southern states. When he was 13, he and his siblings moved to New York City and lived in Harlem. His mother wanted to keep him busy, so she enrolled him in art classes at the Utopia Children's Center. Young Jacob loved to draw patterns, often copying designs from his mother's carpets.

He left school at 16 and worked in a laundromat and a printing shop. But he never stopped making art! He took classes at the Harlem Art Workshop with a well-known artist named Charles Alston. Alston encouraged him to go to the Harlem Community Art Center, led by sculptor Augusta Savage. Savage helped Lawrence get a scholarship to the American Artists School and a paid job through the Works Progress Administration. This program helped artists during the Great Depression. Lawrence continued to learn and grow as an artist in Harlem, which was a very important place for Black artists in the United States. He always focused on showing the history and challenges of African Americans in his art.

The lively and colorful streets of Harlem during the Great Depression inspired Lawrence. He also loved the bright colors and patterns he saw inside people's homes. He often used water-based paints. His paintings became known for their clear shapes, bright colors, and energetic patterns. They showed both daily life in Harlem and important historical events.

Career

From the very beginning, Jacob Lawrence had a special way of working. He created series of paintings that told a story or showed many different parts of a subject. His first series were about important Black historical figures. When he was just 21, his series of 41 paintings about Toussaint L’Ouverture, a Haitian general who led a slave revolution, was shown in a museum. After that, he created series about Harriet Tubman (1938–39) and Frederick Douglass (1939–40). He also painted scenes of everyday life in Harlem and a big series about African-American history (1940–1941).

His teacher, Charles Alston, once said that Lawrence's art was full of "vitality, seriousness and promise." He praised Lawrence for using bright colors and creating exciting art.

On July 24, 1941, Lawrence married another painter named Gwendolyn Knight. She often helped him prepare his painting surfaces and wrote captions for his multi-panel artworks.

The Migration Series

In 1940–41, Lawrence finished his most famous work: a 60-panel series called The Migration of the Negro, now known as the Migration Series. This series tells the story of the Great Migration. This was a time after World War I when hundreds of thousands of African Americans moved from the farms in the South to the big cities in the North, looking for better lives.

Because he used paint that dried quickly, Lawrence planned all 60 paintings ahead of time. He would apply one color to all the paintings where it was needed, then move to the next color. This helped keep all the paintings looking consistent. This series was shown in a New York art gallery, making him the first African-American artist to be represented by such a gallery. This brought him national fame. Parts of the series were even featured in Fortune magazine. The entire series was bought by two museums: the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. They each own half of the paintings.

After this, he created another series of 22 panels about the abolitionist John Brown in 1941–42. Later, he made these paintings into silkscreen prints so more people could see them.

In 1943, a writer for The New York Times called Lawrence's next series about Harlem life "an amazing social document." The writer praised his use of vivid colors and strong, almost abstract style.

World War II Service

In October 1943, during Second World War, Lawrence joined the United States Coast Guard. He worked as a public affairs specialist on the USCGC Sea Cloud, which had the first racially integrated crew. He continued to paint and sketch during his service, showing what war was like around the world. He made 48 paintings during this time, but sadly, all of them were lost.

Lost Works and Post-War Art

In 1944, the MoMA showed all 60 Migration panels along with 8 paintings Lawrence made while in the Coast Guard. After the war, these 8 paintings went missing.

After the war, Lawrence received a special award from the Guggenheim Foundation. In 1946, he was invited to teach art at Black Mountain College.

When he returned to New York, Lawrence kept painting. For a short time in 1949, he stayed at Hillside Hospital in Queens. While there, he created his "Hospital Series," which showed the feelings of people staying in the hospital.

Between 1954 and 1956, Lawrence created a 30-panel series called "Struggle: From the History of the American People." This series showed historical moments from 1775 to 1817. It included stories about the American Revolution and other important events, sometimes focusing on less-known heroes or the contributions of enslaved Black people. Instead of traditional titles, Lawrence used quotes for each panel. For example, a panel about a slave revolt used the words of a man who fought for freedom: "We have no property! We have no wives! No children! We have no city! No country!" Some of these panels were lost for many years, but some have been found recently. In 2021, the Peabody Essex Museum organized an exhibition of all 30 panels, including the newly found ones.

In 1960, the Brooklyn Museum of Art held a big exhibition of Lawrence's work. He was also part of a major show of Black artists in Philadelphia in 1969.

Illustrating for Children

Jacob Lawrence also illustrated several books for children. His book Harriet and the Promised Land (1968) used his paintings to tell the story of Harriet Tubman. This book was praised for its artistic talent and for creating a "spiritual experience" for readers. He also made similar books based on his John Brown and Great Migration series. In 1970, he illustrated a selection of Aesop's Fables.

Teaching and Later Artworks

Lawrence taught art at many schools, including the New School for Social Research and the Art Students League. In 1970, he became a visiting artist at the University of Washington, and then a professor of art there from 1971 to 1986.

After moving to Washington state, he created a series of five paintings about the journey of African-American pioneer George Washington Bush. These paintings are now in the State of Washington History Museum.

He also created several large artworks for public spaces. In 1980, he finished Exploration, a 40-foot-long mural made of porcelain and steel for Howard University. The Washington Post described it as "enormously sophisticated yet wholly unpretentious."

In 1983, Lawrence created eight screen prints called the Hiroshima Series. He chose to illustrate John Hersey's book Hiroshima, showing the emotional and physical destruction of the bombing in an abstract way.

His painting Theater was made for the University of Washington in 1985. In the early 1990s, he painted the Events in the Life of Harold Washington mural for Chicago's Harold Washington Library.

Last Years and Passing

The Whitney Museum of American Art held a major exhibition of Lawrence's entire career in 1974, and the Seattle Art Museum did the same in 1986.

In 1999, Jacob and his wife, Gwendolyn, started the Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation. This foundation helps create, show, and study American art, especially art by African-American artists.

Jacob Lawrence continued to paint until just a few weeks before he passed away from lung cancer on June 9, 2000, at the age of 82.

Personal life

Jacob Lawrence was married to the painter Gwendolyn Knight. She passed away in 2005.

Awards and honors

Jacob Lawrence received many important awards and honors throughout his life:

- 1945: Received a fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation.

- 1970: Awarded the Spingarn Medal by the NAACP for his amazing achievements.

- 1971: Became an associate member of the National Academy of Design.

- 1978: Became a full member of the National Academy of Design.

- 1983: Elected a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

- 1990: Awarded the U.S. National Medal of Arts, one of the highest honors for artists in the United States.

- 1995: Elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

- 1998: Awarded The Washington Medal of Merit, the highest honor in Washington state.

He also received honorary degrees from many universities, including Harvard University and Yale University.

Legacy and Impact

The New York Times called Jacob Lawrence "one of America's leading modern figurative painters" and a passionate storyteller of the African-American experience. He believed that a painting should have "universality, clarity and strength" so that everyone could understand and appreciate it.

After his passing, a big exhibition of his work traveled to many museums, including the Phillips Collection and the Whitney Museum of American Art. His last public artwork, a mosaic mural called New York in Transit, was installed in the Times Square subway station in New York City in 2001.

In 2005, one of his drawings, Dixie Café, was featured on a U.S. postage stamp to honor the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Civil Rights Movement.

In 2007, his painting The Builders (1947) was bought by the White House Historical Association and has been displayed in the Green Room of the White House since 2009.

Many museums have shown special exhibitions of his work, including the Walters Art Museum (2013-2014) and the Phillips Collection (2016-2017), which brought all 60 panels of The Migration Series together.

In 2020, the Peabody Essex Museum organized a major exhibition called Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle, which brought together his "Struggle" series paintings. This exhibition traveled to several other museums.

The Seattle Art Museum offers a special fellowship in his and his wife's name, and the Jacob Lawrence Gallery at the University of Washington School of Art + Art History + Design has an annual residency program.

His artworks are part of the permanent collections of many famous museums worldwide, including the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the National Gallery of Art.

See also

In Spanish: Jacob Lawrence para niños

In Spanish: Jacob Lawrence para niños

- List of African-American visual artists

- List of Federal Art Project artists