Charles Alston facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Alston

|

|

|---|---|

Charles Alston in 1939

|

|

| Born |

Charles Henry Alston

November 28, 1907 |

| Died | April 27, 1977 (aged 69) New York City, U.S.

|

| Education | Columbia University, Teachers College |

| Known for | Muralism, painting, illustration, sculpture |

| Movement | Abstract expressionism |

| Patron(s) | Lemoine Deleaver Pierce |

Charles Henry Alston (born November 28, 1907 – died April 27, 1977) was an important American artist. He was a painter, sculptor, illustrator, and muralist, and also a teacher. Alston lived and worked in Harlem, a famous neighborhood in New York City.

He was a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance, a time when African-American art, music, and literature flourished. Charles Alston was the first African-American supervisor for the Works Progress Administration's Federal Art Project. He designed and painted amazing murals at the Harlem Hospital and the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Building. In 1990, his sculpture of Martin Luther King Jr. became the first image of an African American ever shown at the White House.

Contents

Who was Charles Alston?

His Early Life and Family

Charles Henry Alston was born on November 28, 1907, in Charlotte, North Carolina. He was the youngest of five children. Only three of them lived past infancy: Charles, his older sister Rousmaniere, and his older brother Wendell.

His father, Reverend Primus Priss Alston, was born into slavery in 1851. After the Civil War, he got an education and became a respected minister. He founded St. Michael's Episcopal Church, which had an African-American congregation. Charles's father was known for dedicating his skills to helping the black community. Charles was nicknamed "Spinky" by his father, a name he kept his whole life. When Charles was three, his father suddenly passed away.

In 1913, Charles's mother, Anna Alston, remarried Harry Bearden. Harry was the brother of Romare Bearden's father, making Charles and Romare cousins. Romare and Charles became lifelong friends. As a child, Charles loved copying his older brother Wendell's drawings of trains and cars. He also enjoyed playing with clay, even making a sculpture of North Carolina. He later remembered this as his first art experience. His mother was also a skilled embroiderer and started painting when she was 75.

Moving to New York City

In 1915, Charles's family moved to New York City. Many African-American families moved north during this time, known as the Great Migration. The family settled in Harlem and was considered middle-class. Even during the Great Depression, when many people in Harlem faced economic hardship, the community showed great strength. Charles later showed this strength in his art.

At Public School 179 in Manhattan, Charles's artistic talent was noticed. He was asked to draw all the school posters. He went on to graduate from DeWitt Clinton High School. There, he was recognized for his academic excellence and was the art editor for the school's magazine. He also studied drawing and anatomy at the National Academy of Art.

Higher Education and Art Studies

After high school, Charles Alston went to Columbia University in 1925. He turned down a scholarship to the Yale School of Fine Arts. He first tried architecture and then pre-med, but found that math and science were "not just my bag." He then decided to study fine arts.

At Columbia, Alston joined a fraternity and drew cartoons for the school magazine. He also explored Harlem's restaurants and clubs, which helped him develop a love for jazz and black music. In 1929, he graduated and received a scholarship to Teachers College, where he earned his Master's degree in 1931.

Later Life and Family

From 1942 to 1943, Alston served in the army at Fort Huachuca in Arizona. After returning to New York, he married Dr. Myra Adele Logan on April 8, 1944. Myra was an intern at the Harlem Hospital, where they met while Charles was working on a mural project.

They lived in a home on Edgecombe Avenue, which also included his art studio. The couple lived close to family, and Alston enjoyed cooking for their frequent gatherings while Myra played the piano. In January 1977, Myra Logan passed away. A few months later, on April 27, 1977, Charles Alston also passed away after a long illness.

Charles Alston's Art Career

Teaching and Early Art Influences

While earning his master's degree, Alston worked with children at the Utopia Children's House. He also began teaching at the Harlem Community Art Center, which was founded by Augusta Savage. Charles Alston taught the 10-year-old Jacob Lawrence, who later became a very famous artist. Alston was introduced to African art by the poet Alain Locke.

In the late 1920s, Alston and other black artists, including his cousin Romare Bearden, refused to show their art in certain exhibitions. These shows only featured black artists and were often for white audiences. Alston and his friends felt this was a form of segregation. They wanted their art to be shown alongside artists of all backgrounds.

Documenting Life in the South

In 1938, Alston received money from the Rosenwald Fund to travel to the South. This was his first time back since he was a child. He took many photographs of rural life, which he used as inspiration for his paintings. These paintings showed scenes of black life in the South. For example, his 1940 painting Tobacco Farmer shows a young black farmer with a serious look on his face.

Illustrations and Public Service

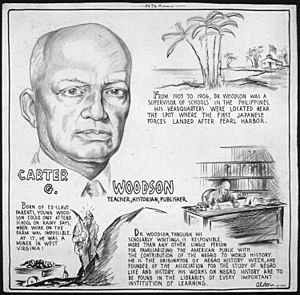

During the 1930s and early 1940s, Alston created illustrations for popular magazines like Fortune and The New Yorker. He also designed album covers for jazz musicians like Duke Ellington. In 1940, Alston became a staff artist at the Office of War Information. He created drawings of important African Americans. These images were used in over 200 black newspapers across the country to help build good relationships with black citizens.

Becoming a Leading Artist and Teacher

Eventually, Alston stopped doing commercial work to focus on his own art. In 1950, he made history by becoming the first African-American instructor at the Art Students League. He taught there until 1971. That same year, his painting Painting was shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and it was one of the few pieces the museum bought.

In 1953, Alston had his first solo art show at the John Heller Gallery. He showed his work there five times between 1953 and 1958. In 1956, he became the first African-American instructor at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). He taught there for a year before traveling to Belgium to help MoMA and the U.S. State Department. He helped organize the children's community center at Expo 58, a big world's fair.

The Spiral Group and Activism

In 1963, Alston co-founded a group called Spiral with his cousin Romare Bearden and Hale Woodruff. Spiral was a place for artists to talk and explore art together. They discussed how black artists should relate to American society during a time of segregation. Alston was known as an "intellectual activist." In 1968, he spoke at Columbia University about his activism.

In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Alston to the National Council of Culture and the Arts. In 1969, Mayor John Lindsay appointed him to the New York City Art Commission. In 1973, he became a full professor at City College of New York, where he had taught since 1968.

Alston's Artistic Style

Painting People and Culture

Charles Alston shared a studio space at 306 W. 141st Street, which became a meeting place for artists, photographers, musicians, and writers. Other artists like Jacob Lawrence also worked there. In these early years, Alston focused on mastering portraiture. His early works, like Portrait of a Man (1929), show his detailed and realistic style.

His paintings Girl in a Red Dress (1934) and The Blue Shirt (1935) show his modern techniques for portraits of young people in Harlem. Blue Shirt is thought to be a portrait of Jacob Lawrence. He also created Man Seated with Travel Bag (c. 1938–40), which shows a more serious environment.

After his trip to the South, Alston started his "family series" in the 1940s. These portraits often showed intense and angular faces of young people. They also showed the influence of African sculpture on his work. Later family portraits explored religious symbolism, color, and space. His family group portraits often had faceless figures. Alston said this was how white America viewed black people. Paintings like Family (1955) show a seated woman and a standing man with two children. The parents look serious, while the children are described as hopeful.

Jazz music was very important to Alston, both in his art and his social life. He showed this in works like Jazz (1950) and Harlem at Night. Blues Singer #4 shows a female singer on stage in a bold red dress. Girl in a Red Dress is believed to be Bessie Smith, a famous blues singer whom he drew many times.

The civil rights movement of the 1960s deeply influenced his art. He created works that expressed feelings about inequality and race relations in the United States. One of his religious artworks, Christ Head (1960), showed an angular portrait of Jesus Christ. Seven years later, he created You never really meant it, did you, Mr. Charlie?, which shows a black man looking very frustrated.

Modern Art and Black and White Works

In the mid-1950s, Alston began creating more modernist paintings. Woman with Flowers (1949) is seen as a tribute to the artist Amedeo Modigliani. His painting Ceremonial (1950) shows how African art influenced him. His untitled works from this time show his use of color layers to create simple abstract still lifes. Symbol (1953) relates to Pablo Picasso's famous painting Guernica, which Alston admired.

His last work of the 1950s, Walking, was inspired by the Montgomery bus boycott. It represents "the surge of energy among African Americans to organize in their struggle for full equality." Alston said, "The idea of a march was growing....It was in the air...and this painting just came. I called it Walking on purpose. It wasn't the militancy that you saw later. It was a very definite walk-not going back, no hesitation."

The civil rights movement of the 1960s had a big impact on Alston. In the late 1950s, he started working in black and white, and continued this until the mid-1960s. This period is considered one of his most powerful. Some of these works are simple abstract designs of black ink on white paper. Untitled (c. 1960s) shows a boxing match, trying to capture the drama with just a few brushstrokes. Black and White #1 (1959) is one of his most important works from this period. Gray, white, and black colors come together on an abstract canvas.

Murals: Art for Everyone

Charles Alston's mural work was inspired by artists like Aaron Douglas, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco. He was elected to the board of directors of the National Society of Mural Painters in 1943. He created murals for many places, including the Harlem Hospital, Golden State Mutual, and the American Museum of Natural History.

Harlem Hospital Murals

In 1935, Alston became the first African-American supervisor for the WPA's Federal Art Project (FAP) in New York. This was his first mural project. He was given the chance to oversee a group of artists creating murals for the Harlem Hospital. This was the first government art project ever given to African-American artists.

Alston also got to create his own murals for the hospital: Magic in Medicine and Modern Medicine. These two paintings, completed in 1936, showed the history of medicine in the African-American community. Magic in Medicine shows African culture and holistic healing. It is considered one of "America's first public scenes of Africa."

All the mural sketches were accepted by the FAP. However, hospital officials rejected four of them, saying they had too much African-American representation. The artists fought back, writing letters to get support. Four years later, they won the right to complete the murals. The sketches for Magic in Medicine and Modern Medicine were even shown at the Museum of Modern Art.

Condition of the Murals

Alston's murals were hung in the Women's Pavilion of the hospital. They were placed over uncapped radiators, which caused the paintings to get damaged by steam. Plans to fix the radiators failed. In 1959, Alston estimated that it would cost $1,500 to fix the murals, but the money was never found.

In 1968, after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Alston was asked to create another mural for the hospital. It was to be placed in a pavilion named after the civil rights leader.

After Alston's death in 1977, a group of artists and historians, including Romare Bearden, worked to save the murals. Their request for restoration was approved, and work began in 1979. However, the murals began to deteriorate again. In 1991, a program was launched to restore them further. A grant from Alston's sister and step-sister helped complete a restoration in 1993. In 2005, Harlem Hospital announced a $2 million project to fully conserve Alston's murals and three other pieces from the original project.

Golden State Mutual Murals

In the late 1940s, Alston worked on a mural project for the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company. The company wanted art that showed African-American contributions to the settling of California. Alston worked with Hale Woodruff on these murals in a large studio in New York.

The artworks are considered "priceless contributions to American narrative art." They consist of two large panels: Exploration and Colonization by Alston and Settlement and Development by Woodruff. Alston's painting covers the period from 1527 to 1850. It shows important figures like mountain man James Beckwourth, Biddy Mason, and William Leidesdorff. Both artists stayed in touch with African Americans on the West Coast while creating the murals, which influenced their content. The murals were shown to the public in 1949 and have been on display in the lobby of the Golden State Mutual Headquarters.

Due to money problems, Golden State had to sell its art collection in the early 2000s. The National Museum of African American History and Culture offered to buy the artworks for $750,000, but they were estimated to be worth at least $5 million. Supporters tried to protect the murals by getting city landmark status.

Sculpture: Three-Dimensional Art

Alston also created sculptures. His Head of a Woman (1957) shows his modern approach to sculpture, where facial features were suggested rather than fully detailed.

In 1970, Alston was asked to create a bust (a sculpture of a head and shoulders) of Martin Luther King Jr.. Only five copies were made. In 1990, Alston's bronze bust of Martin Luther King Jr. became the first image of an African American to be displayed in the White House. When Barack Obama became the first black president in 2009, he brought this bust into the Oval Office. This was the first time an image of an African American was displayed in the president's main work room. The bust became a very important piece of art seen in official photos with visiting leaders.

Art During World War II

During World War II, Charles Alston created over one hundred illustrations for the U.S. Office of War Information. These drawings supported the country's efforts in the war. They were made specifically for black newspapers to address issues important to the black community at that time.

Major Exhibitions of His Work

- A Force for Change, group show, 2009, Spertus Museum, Chicago

- Canvasing the Movement, group show, 2009, Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture

- On Higher Ground: Selections From the Walter O. Evans Collection, group show, 2001, Henry Ford Museum, Michigan

- Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance, group show, 1998, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- In the Spirit of Resistance: African-American Modernists and the Mexican Muralist School, group show, 1996, The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York

- Charles Alston: Artist and Teacher, 1990, Kenkeleba Gallery, New York

- Masters and Pupils: The Education of the Black Artist in New York, 1986, Jamaica Arts Center, New York

- Hundred Anniversary Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, 1975, Art Students League of New York, New York

- Solo exhibition, 1969, Huntington Hartford Gallery of Modern Art, New York.

- Solo exhibition, 1968, Fairleigh Dickinson University, New Jersey

- A Tribute to Negro Artists in Honor of the 100th Anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, group show, 1963, Albany Institute of History and Art

Major Collections Featuring His Art

- Hampton University

- Harmon and Harriet Kelly Foundation for the Arts

- National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

- Kalamazoo Institute of Arts, Kalamazoo, MI

- National Museum of African American History and Culture

- Whitney Museum of American Art

Images for kids

-

Pvt. Alston with his art student and cousin, Romare Bearden (right), discussing one of his paintings, Cotton Workers, in 1944. Both were members of the 372nd Infantry Regiment stationed in New York City.

-

Alston's illustration of African-American historian Carter G. Woodson for the Office of War Information

See also

In Spanish: Charles Alston para niños

In Spanish: Charles Alston para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |