National Museum of African American History and Culture facts for kids

|

|

Exterior of the museum

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Established | December 16, 2003 (establishment) September 24, 2016 (building dedication on The Mall) |

|---|---|

| Location | 1400 Constitution Ave, NW Washington, DC 20560 |

| Type | History museum |

| Collections | African-American history, art, music |

| Collection size | 40,000 (approximate) |

| Visitors | 1,092,552 (2022) |

| Architect | Freelon Group/Adjaye Associates/Davis Brody Bond |

| Public transit access | |

The National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), also called the Blacksonian, is a special museum in Washington, D.C. It is part of the Smithsonian Institution. The museum was created in 2003. Its main building opened in 2016 with a ceremony led by President Barack Obama.

People wanted a national museum about African-American history and culture for a long time. Ideas for it started as early as 1915. But the real effort to build it began in the 1970s. After many years, a law was passed in 2003 to create the museum. A place for the museum was chosen in 2006. The design by Freelon Group/Adjaye Associates/Davis Brody Bond was picked in 2009. Building started in 2012 and finished in 2016.

The NMAAHC is the biggest museum in the world focused on African-American history and culture. In 2022, over 1 million people visited it. It was the second most-visited Smithsonian Museum that year. The museum has more than 40,000 items. About 3,500 of these items are on display. The building is 10 stories tall, with five floors above ground and five below. It has received great praise for its design and exhibits.

Contents

History of the Museum

Early Ideas for a Museum

The idea for a national museum about African-American history began a long time ago. In 1915, African-American veterans from the Union Army met in Washington, D.C. They were upset about the unfair treatment they still faced. They decided to create a memorial to celebrate African-American achievements.

In 1929, President Herbert Hoover appointed a group to build a "National Memorial Building." This building would show African-American achievements in arts and sciences. But the plan did not get enough support or money. For the next 40 years, many ideas for a museum were suggested, but none succeeded.

In the 1970s, new proposals for a museum started. In 1981, Congress approved a museum in Ohio. This museum was built with private money and opened in 1987. Around the same time, a man named Tom Mack began pushing for a museum in Washington, D.C. He wanted a special museum just for African Americans.

In 1985, Tom Mack got support from Representative Mickey Leland. Leland helped pass a resolution in 1986 that supported an African-American museum. This attention made the Smithsonian Institution think about showing more African-American history. In 1987, the National Museum of American History had a big exhibit called "Field to Factory." It showed the journey of Black Americans from the South to other parts of the country.

This exhibit encouraged Tom Mack to keep working for a museum. But his efforts faced challenges. Some groups, like the African American Museum Association (AAMA), worried that a national museum would take money and artifacts from smaller local museums. They suggested a fund to help local museums instead. Others questioned if the Smithsonian, which was mostly white-led, could properly run an African-American history museum.

In 1988, Representative John Lewis and Representative Leland introduced a bill for a stand-alone museum. But it was too expensive and did not pass. They tried again in 1989, but the bill failed again. However, the Smithsonian Institution started to support the idea more. In 1989, the Smithsonian hired Claudine K. Brown to study the museum idea. Her study said that a national museum was needed. It also said the Smithsonian needed to do better at showing African-American culture.

In 1990, the Smithsonian formed an advisory board. This board studied the idea for a year. In 1991, the board said a national museum was a good idea. The Smithsonian leaders agreed. They suggested putting the museum in an existing building, the Arts and Industries Building. They also agreed to keep the Anacostia Community Museum separate. And they supported a program to help local African-American museums.

Efforts in the 1990s

In 1992, the Smithsonian sent a museum bill to Congress. But some people thought the Arts and Industries Building was too small. The bill did not pass. In 1994, Senator Jesse Helms stopped the bill from being voted on.

In 1995, the Smithsonian changed its mind. It suggested a new "Center for African American History and Culture" instead of a new museum. The new Smithsonian Secretary, Ira Michael Heyman, even questioned if "ethnic" museums were needed. Many people saw this as a step backward.

Meanwhile, other cities built their own African-American museums. Detroit opened a large museum in 1997. Cincinnati started raising money for the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. In 2000, a private group suggested building a museum on the Anacostia River.

Passing the Federal Law

In 2001, John Lewis and Representative J. C. Watts brought the museum idea back to Congress. The Smithsonian leaders changed their minds again. They decided to support a stand-alone National Museum of African American History and Culture. They asked Congress to create a study group.

President George W. Bush signed a law on December 29, 2001. This law created a group to study if a museum was needed. It also looked at how to raise money and where to put it. President Bush said he thought the museum should be on the National Mall.

The study group worked for almost two years. In 2003, they said a museum was definitely needed. They suggested a very important spot near the Capitol Reflecting Pool. They also said the museum should be 350,000 square feet and cost $360 million to build. Half the money would come from private donations, and half from the government.

The museum's location became a big discussion point. Some people thought the Capitol Hill site was too crowded. Other places were suggested. To save the bill, supporters agreed to drop the Capitol Hill site. This helped the law pass in November 2003. President Bush signed it on December 16, 2003. The law set aside money for planning and choosing a site. It also created a committee to pick the best location.

Choosing the Site and Design

In 2005, President Bush again said the museum should be on the National Mall. The site selection committee finally made its choice in January 2006. They picked a spot west of the National Museum of American History. This area was part of the Washington Monument grounds.

In March 2005, Lonnie G. Bunch III was named the Director of the new museum.

In 2008, a competition was held to design the museum building. The building needed to be 350,000 square feet, with three stories underground and five above. It had to be environmentally friendly and meet strict security rules. The design also had to respect the Washington Monument and show the African-American experience. It needed to reflect hope and joy, but also acknowledge the difficult parts of history.

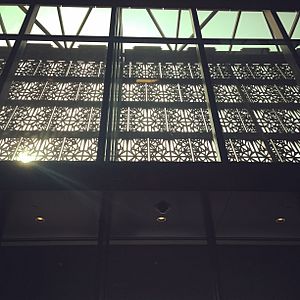

Six teams of architects were chosen as finalists. The design by the Freelon Group/Adjaye Associates/Davis Brody Bond team won. Their design featured an upside-down pyramid shape. It was surrounded by a special bronze screen. This screen was inspired by a crown from the Yoruba culture in Africa.

The design was slightly changed as it went through approval. The building was moved to give a better view of the Washington Monument. The upper floors were made a bit smaller. A pond, garden, and bridge were added to the entrance. This was meant to remind visitors of the journey enslaved people made to America.

The Smithsonian thought the museum would open in 2015. Until then, the museum had a small gallery inside the National Museum of American History.

Many people and groups donated money to the museum. In 2013, media leader Oprah Winfrey gave $12 million. She had also given $1 million in 2007. The museum's theater was named after her. The GM Foundation also gave $1 million in 2014.

Building Design Changes

The special screen around the building was changed in 2012. It was originally planned to be made of bronze. But because of cost, it was changed to bronze-painted aluminum. Some people worried this would not look as good as real bronze.

The landscaping around the museum also changed. The first plan had a wetland with a creek and plants. But this was too expensive. So, a low granite wall was approved instead.

Discussions about the bronze screen continued. Architects tried different materials and paints. Finally, a special coating called polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) was approved in 2014. This coating helped the building achieve the desired look.

Building the Museum

The museum's groundbreaking ceremony happened on February 22, 2012. President Barack Obama and museum director Lonnie Bunch spoke at the event.

The museum became the deepest on the National Mall. Workers dug 80 feet down for the foundations. Large items, like a segregated railroad passenger car and a guard tower from a prison, were installed early. The museum had to be built around them because they were too big to bring in later.

The building has a unique design. The upper floors are open spaces without many columns. To support them, four huge walls were built with steel frames and concrete. A large porch covers the main entrance. Inside, a beautiful spiral staircase connects the upper floors.

The museum's steel structure was finished in January 2015. Glass for the windows was put in by April 2015. Then, the 3,600 bronze-colored panels for the building's special screen were installed.

In October 2014, the museum had raised $162 million for its building. The Smithsonian also helped with funding. The museum was recognized with the Beazley Design of the Year award in 2017 for its beautiful design and cultural impact.

Opening Day

In January 2016, the Smithsonian announced the museum would open on September 24, 2016. President Barack Obama would officially open it. Special events were planned for a week, and the museum would stay open longer to welcome visitors.

Museum officials prepared the building for the exhibits. They installed items that could handle dust and humidity first. More delicate items were added once the building's environment was stable. The museum planned 11 initial exhibits with 3,000 items.

Leading up to the opening, more donations came in. David Rubenstein gave $10 million, and Wells Fargo gave $1 million. Microsoft and Google also donated $1 million each. Google even helped create a 3D interactive exhibit for visitors.

On September 16, 2016, violinist Edward W. Hardy performed music inspired by Black music history. This was part of the opening celebrations.

On September 23, 2016, it was announced that Robert F. Smith gave $20 million. This was the second-largest gift to the museum, after Oprah Winfrey's donations.

Filmmaker Ava DuVernay created a special film for the museum's opening. The film, August 28: A Day in the Life of a People, showed six important events in African-American history that happened on August 28. It starred famous actors like Lupita Nyong'o and Don Cheadle.

On September 24, 2016, President Barack Obama officially opened the museum. He was joined by four generations of the Bonner family, including 99-year-old Ruth Bonner. Instead of cutting a ribbon, they rang the Freedom Bell. This bell came from the first Baptist church founded by and for African Americans in 1776. During his speech, Obama spoke about the importance of the museum.

The total cost for the museum's design, building, and exhibits was $540 million. The museum's fundraising campaign raised $386 million, which was more than their goal.

Visiting the Museum

More than 600,000 people visited the museum in its first three months. The Smithsonian requires all visitors to have a ticket. They use timed-entry tickets, which means visitors enter at a specific time. This helps manage the large crowds.

After six months, 1.2 million people had visited. Visitors spent an average of six hours at the museum, which was longer than expected. The museum's popularity caused some crowding in certain areas, especially at the start of the exhibits. Museum staff worked to manage the flow of visitors.

By the end of 2018, nearly 5 million people had visited the museum since it opened. It became a very popular place for tourists from all over the world.

Museum Collections and Exhibits

Online Presence

In 2007, the NMAAHC was the first major museum to open online before its building was finished. Its website allowed people to share their own stories and pictures about African-American culture.

Exhibits Before Opening

In 2012, the NMAAHC worked with the Thomas Jefferson Foundation to create an exhibit called "Slavery at Jefferson's Monticello: Paradox of Liberty." This exhibit explored how slavery was part of Thomas Jefferson's life. It was shown at the National Museum of American History.

Other exhibits before the museum opened included ones about the Apollo Theater, civil rights, and African-American portraits.

Important Items in the Collection

The museum has over 40,000 objects in its collection. About 3,500 of these are on display. These items are carefully cared for and stored in a special environment.

In November 2016, NBA player LeBron James donated $2.5 million to support the museum's exhibit on boxer Muhammad Ali.

Here are some notable items you can see:

Items from Before the 1900s

- Pieces from the São José Paquete Africa, a sunken slave ship found off South Africa.

- A letter from Toussaint L'Ouverture, a leader of the Haitian Revolution.

- A money box used by Richard Allen, who founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

- A Bible owned by Nat Turner, who led a slave rebellion in 1831.

- A slave cabin from South Carolina, taken apart and rebuilt inside the museum.

- Ashley's Sack, a special cloth sack given from a mother to her daughter when the daughter was sold away.

- Feet and wrist chains used on enslaved people before 1860.

- Items owned by Harriet Tubman, including eating tools and a shawl given to her by Queen Victoria.

- An 1874 home built by the Jones family, who were freed slaves in Maryland.

Items from the 1900s and 2000s

- A railroad car from the Jim Crow era, used by African-American passengers.

- A "colored" drinking fountain sign from the Jim Crow era.

- Dresses by fashion designer Ann Lowe, who designed for famous families.

- A recreation of "Mae's Millinery Shop," one of the first businesses in Philadelphia owned by an African-American woman.

- The Purple Heart medal and footlocker of James L. McCullin, a Tuskegee Airmen member.

- A biplane used to train the Tuskegee Airmen.

- A guard tower and cell from the Louisiana State Penitentiary (Angola) prison. These items show how ideas about slavery continued in the prison system.

- Charlie Parker's custom-made saxophone.

- The glass-topped casket used for 14-year-old Emmett Till, whose death helped start the Civil Rights Movement.

- The dress Rosa Parks was sewing the day she refused to give up her seat on a bus in 1955.

- Louis Armstrong's trumpet.

- Muhammad Ali's boxing gloves and headgear.

- A cape and jumpsuit owned by James Brown.

- The "Mothership" prop used by George Clinton and his bands.

- Costumes designed by Geoffrey Holder for the musical The Wiz.

- A red Cadillac convertible owned by Chuck Berry.

- Gymnastic equipment used by champion Gabby Douglas at the 2012 Summer Olympics.

- Handcuffs used to arrest Harvard University professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. in 2009.

- Items from President Barack Obama's 2008 presidential campaign.

- A pair of hand-painted sneakers called "Obama 08."

- NBA player Kobe Bryant's uniform from the 2008 NBA Finals.

Modern Art Installations

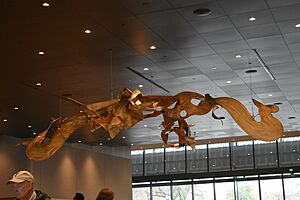

- Swing Low (2016) by Richard Hunt is a large bronze sculpture in the main hall. It represents the movement in spiritual songs.

- Yet Do I Marvel (Countee Cullen) by Sam Gilliam has five colorful panels. It was inspired by a poem about creativity.

- The Liquidity of Legacy (2016) by Chakaia Booker is about how changes shape people's lives and legacies.

Museum Leadership

Lonnie Bunch III was the museum's first director, starting in 2005. He oversaw the collections, traveling exhibits, and the building's construction. In 2019, Bunch became the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, the first African American to hold this position. After an interim director, poet and professor Kevin Young was appointed director in September 2020.

Sweet Home Café

The Sweet Home Café is a restaurant inside the museum. It serves lunch and has 400 seats. Jerome Grant is the executive chef. The restaurant offers food from four different regions of the United States: the Agricultural South, the Creole Coast, the North States, and the Western Range. Each station has dishes important to the African-American experience.

The idea for the café came from the successful Mitsitam Café at the National Museum of the American Indian. Food scholar Jessica B. Harris researched African-American food history for the museum. Chefs and historians worked for two years to create the menu. The goal was to show the different foods African Americans ate and their impact on American cooking. Chef Carla Hall is a "culinary ambassador" for the restaurant.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Museo Nacional de Historia y Cultura Afroamericana para niños

In Spanish: Museo Nacional de Historia y Cultura Afroamericana para niños

- List of museums focused on African Americans

- List of most-visited museums in the United States

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |