Toussaint Louverture facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Toussaint Louverture

|

|

|---|---|

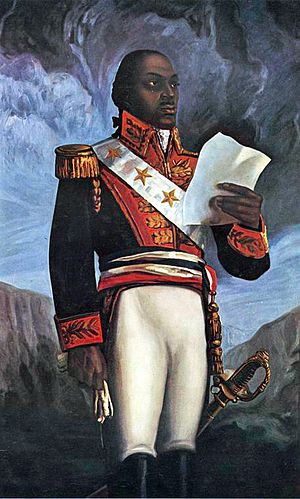

Posthumous 1813 painting of Louverture

|

|

| Governor-General of Saint-Domingue | |

| In office 1797–1801 |

|

| Appointed by | Étienne Maynaud |

| Preceded by | Inaugural holder |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 20 May 1743 Cap-Français, Saint-Domingue |

| Died | 7 April 1803 (aged 59) Fort-de-Joux, First French Republic |

| Spouses | Cécile Suzanne Simone Baptiste Louverture |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

Spanish Army French Army French Revolutionary Army Armée Indigène |

| Years of service | 1791–1803 |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | Haitian Revolution |

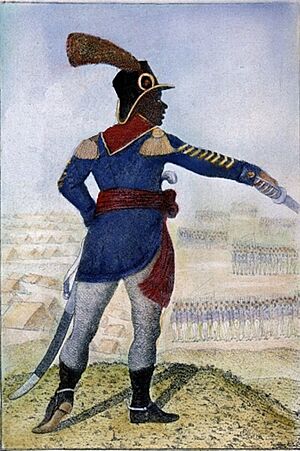

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture (French: [fʁɑ̃swa dɔminik tusɛ̃ luvɛʁtyʁ]; also known as Toussaint L'Ouverture or Toussaint Bréda; 20 May 1743 – 7 April 1803) was a brave Haitian general. He was the most important leader of the Haitian Revolution. During his life, Louverture first fought against the French. Then he fought for them, and finally against France again. He fought for Haiti's freedom.

As a revolutionary leader, Louverture was very smart in military and political matters. He helped turn a small slave rebellion into a big revolutionary movement. Today, Louverture is known as the "Father of Haiti."

Louverture was born into slavery in the French colony of Saint-Domingue. This place is now known as Haiti. He was a strong Catholic. He became a freeman before the revolution started. Once free, he thought of himself as French for most of his life. As a freeman, he tried to move up in society. He faced racism but gained and lost money. He worked as a planter, coachman, and miller. When the Haitian Revolution began, he was almost 50 years old. He started his military career as a helper to Biassou. Biassou was an early leader of the 1791 fight for freedom.

At first, Louverture joined with the Spaniards from nearby Santo Domingo. But he switched to the French side when their new government ended slavery. Louverture slowly took control of the whole island. He used his political and military skills to become the most powerful leader.

During his time in power, he worked to make Saint-Domingue's economy strong and keep it safe. He was worried about the economy, which had stopped growing. So, he brought back the plantation system using paid workers. He also made trade agreements with the United Kingdom and the United States. He kept a large, well-trained army. Even though Louverture did not break ties with France, he made his own independent constitution in 1801. This constitution named him Governor-General for Life. This was against Napoleon Bonaparte's wishes.

In 1802, a French general, Jean-Baptiste Brunet, invited him to a meeting. But Louverture was arrested when he arrived. He was sent to France and put in jail at the Fort de Joux. He died in 1803. Even though Louverture died before the end of the Haitian Revolution, his work helped the Haitian army win. The French lost many soldiers to battles and yellow fever. They left Saint-Domingue for good that same year. The revolution continued under Louverture's helper, Jean-Jacques Dessalines. He declared Haiti independent on January 1, 1804. This created the country of Haiti.

Early Life and Freedom

Birth and Family

Louverture was born into slavery. He was the oldest son of Hyppolite and Pauline. His father, Hyppolite, was from West Africa. His mother, Pauline, was from the Aja people. Toussaint was his birth name. His parents were forced into slavery because of wars in Africa. They were sold to a French slave ship and brought to the Caribbean. French law made slaves become Catholics and gave them European names. Toussaint's father was named Hyppolite when he was baptized.

Louverture was likely born on the Bréda plantation in Saint-Domingue. He spent most of his life there before the revolution. His parents had several more children. Toussaint became closest to his younger brother, Paul. All his siblings were baptized into the Catholic Church. Pierre-Baptiste Simon, a carpenter on the plantation, was Toussaint's godfather. He became like a parent to Toussaint's family.

Growing Up on the Plantation

When he was young, Toussaint first learned the African Fon language. Then he learned Haitian Kreyòl. Later, he learned Standard French. Even though he became known for being strong, he was called Fatras-Bâton ("sickly stick") when he was young. This was because he was small and thin.

Toussaint and his siblings were trained as domestic servants. Louverture became an equestrian and coachman. He was good at handling horses and oxen. This allowed him to work in the manor house and stables. This was better than the hard work in the sugar cane fields. Even with this better life, Toussaint was proud. He sometimes fought with white workers on the plantation. He was protected by the plantation overseer, François Antoine Bayon de Libertat.

Gaining Freedom

For a long time, people thought Louverture was a slave until the revolution. But later, records showed he was a freeman between 1772 and 1776. This meant he was freed before the revolution. He even wrote a letter in 1797 saying he had been free for over twenty years. After being freed, he took the name Toussaint de Bréda.

Toussaint became part of the gens de couleur libres (free people of color). This group included freed slaves and mixed-race people. They felt Saint-Domingue was their home. Louverture wanted to get rich like the wealthy planters. He rented a small coffee plantation and owned some slaves. One of these slaves might have been Jean-Jacques Dessalines. Dessalines later became one of Louverture's most loyal helpers.

Marriages and Family Life

Between 1761 and 1777, Louverture married his first wife, Cécile, in a Catholic ceremony. They had two sons and a daughter. Louverture bought the freedom of Cécile, their children, and his sister. He also freed other family members. His first marriage ended when his coffee plantation failed. Cécile left him for a rich planter. Louverture then started a relationship with Suzanne.

In 1782, Louverture married his second wife, Suzanne Simone-Baptiste. She might have been his cousin. He had many children with his two wives and other women. His oldest child, Toussaint Jr., died from a fever in 1785. Suzanne's oldest child, Placide, was adopted by Louverture and raised as his own. Louverture had two sons with Suzanne: Isaac and Saint-Jean. They remained enslaved until the revolution.

In the 1780s, Louverture worked to get back the wealth he had lost. He returned to the Bréda plantation as a paid worker. He looked after the livestock and horses. He also became a muleteer and master miller. He even helped organize the workers. He bought a young female slave and traded her to protect his foster mother, Pelage, from being sold. By the start of the revolution, Louverture had saved some money. He bought land next to the Bréda property to build a house. He was almost 48 years old at this time.

Education and Knowledge

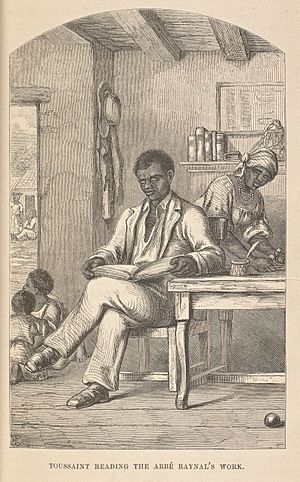

Louverture learned some things from his godfather, Pierre-Baptiste. His letters show he knew about Epictetus, a philosopher who was once a slave. His speeches showed he knew about Machiavelli. Some people think he was influenced by Abbé Raynal, a French writer who criticized slavery. Raynal had predicted a slave revolt in the West Indies.

Louverture also learned about religion from Jesuit and Capuchin missionaries. He learned about medicine from African folk medicine and from hospitals. He could not write in 1778–1781. During his military career, he told his secretaries what to write. But he did learn to write later in his life. His French spelling was like the Haitian Kreyòl he spoke.

The Haitian Revolution

Starting the Fight for Freedom

From 1789, black and mixed-race people in Saint-Domingue were inspired to rebel. The French Revolution in France also played a part. In 1789, two mixed-race merchants, Vincent Ogé and Julien Raimond, asked the French government to give more rights to wealthy mixed-race people. They were denied. Ogé and Jean-Baptiste Chavannes started a small revolt in 1790. They were captured and publicly executed in February 1791.

For the enslaved people, conditions were getting worse. This made them want to revolt even more. The French Revolution's ideas about rights for all men also inspired revolts. Many Catholic slaves and freedmen, including Toussaint, saw themselves as French and loyal to the king. They wanted to keep the legal protections given to black citizens by King Louis XVI.

On August 14, 1791, about 200 black and mixed-race people met secretly. They were slave foremen, Creoles, and freed slaves. They met to plan their revolt. Leaders like Dutty François Boukman, Jean-François Papillon, and Georges Biassou were there. Toussaint nominated Georges Biassou as leader. Toussaint joined as a secretary and lieutenant. He commanded a small group of soldiers. During this time, Toussaint started using the name Monsieur Toussaint. This title was usually only for white people. He helped plan the rebellion and got supplies from Spanish supporters. Louverture and other rebels wore white ribbons and crosses to show they supported the king.

A few days later, a Vodou ceremony at Bois Caïman marked the start of the big slave rebellion. This happened in the north, where there were many plantations and enslaved people. Louverture did not join the first parts of the rebellion. He spent weeks sending his family to safety in Santo Domingo. He also helped his old overseer, Bayon de Libertat, and his family escape the island. He even supported them financially later.

In 1791, Louverture helped with talks between rebel leaders and the French Governor. They wanted white prisoners released and workers to return. In exchange, they asked for no whips, an extra day off, and freedom for imprisoned leaders. The offer was rejected. Louverture then helped stop the killing of white prisoners. He hoped to present the rebels' demands, but the colonial assembly refused to meet.

Becoming a Military Leader

In 1792, Louverture became a leader in an alliance between the black rebellion and the Spanish. He managed a fort called La Tannerie. He also kept a line of posts between rebel and colonial areas. He became known for his strictness. He trained his men in guerrilla tactics and European war styles. In January 1793, he lost La Tannerie to the French General Étienne Maynaud de Bizefranc de Laveaux. But in these battles, the French saw him as an important military leader.

Around 1792–1793, Toussaint took the name Louverture. This means "opening" or "the one who opened the way." Some people spell it "L'Ouverture," but he did not. It likely refers to his ability to create openings in battle. Some say it was because of a gap between his front teeth.

Joining Forces with Spain

Louverture started using words like freedom and equality, like the French Revolution. He had been willing to bargain for better conditions for slaves. But then he became set on ending slavery completely. In May 1793, Jean-François and Biassou joined with the Spanish. Louverture likely joined them in early June. He had tried to talk to the French general before, but his conditions were not accepted. At this time, the French had not offered freedom to the enslaved. So, conditions under the Spanish seemed better.

On August 29, 1793, Louverture made his famous declaration at Camp Turel. He spoke to the black people of Saint-Domingue. On the same day, the French commissioner, Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, declared all slaves in French Saint-Domingue free. He hoped to get the black troops to join his side. But this did not work at first. Louverture and other leaders knew Sonthonax might not have the power to do this.

However, on February 4, 1794, the French government officially ended slavery. Louverture had been talking with the French general Étienne Maynaud de Bizefranc de Laveaux for months. His competition with other rebel leaders was growing. The Spanish were also becoming suspicious of his power.

Louverture's army was very successful. They helped the Spanish gain much land. They also captured the port town of Gonaïves in December 1793. But problems grew between Louverture and the Spanish leaders. His new Spanish superior, Juan de Lleonart, did not like the black soldiers. Lleonart did not support Louverture in March 1794. This was when Biassou was stealing supplies and selling families of Louverture's men as slaves. Louverture refused to sell enslaved women and children to the Spanish. This showed that Louverture was not seen as equal to the other black generals by the Spanish.

On April 29, 1794, black troops attacked the Spanish at Gonaïves. They said they were fighting for "the King of the French." Many people were killed. Louverture is thought to be behind this attack, even though he was not there. He wrote to the Spanish saying he was innocent. But on May 18, Louverture said he was responsible. By then, he was fighting for the French.

Joining Forces with France

Historians debate when and why Louverture switched sides to the French. Some say he joined the French in June 1794 after learning about the end of slavery. Others say he cared more about his own safety and joined the French on May 4, 1794. A letter from Toussaint to General Laveaux confirms he was fighting for the French by May 18, 1794.

In the first weeks, Louverture removed all Spanish supporters from the areas he controlled. He was attacked from many sides. His former rebel friends were now fighting him for the Spanish. As a French commander, he also faced British troops. The British had landed on Saint-Domingue in September. They hoped to take over the rich island. The British promised to bring back slavery if they won. This angered those who wanted to end slavery.

Louverture combined his 4,000 men with Laveaux's troops. His officers now included his brother Paul, his nephew Moïse, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and Henri Christophe. Soon, Louverture ended the Spanish threat to French Saint-Domingue. The Treaty of Basel in July 1795 ended fighting between France and Spain. Black leaders Jean-François and Biassou continued to fight Louverture until November. Then they left for Spain and Florida. Most of their men joined Louverture's forces. Louverture also fought the British. He used guerrilla tactics to keep them contained.

Rebuilding and Leadership

In 1795 and 1796, Louverture also focused on bringing back farming and exports. He wanted to keep peace in the areas he controlled. He believed that the freedom of Saint-Domingue depended on a strong economy. He was respected and used both talking and force to get workers back to the plantations. These workers were now free and paid. Workers often rebelled because of bad conditions or fear of slavery returning. They wanted their own small farms instead of working on plantations.

Louverture also managed rivals for power. The most serious was Jean-Louis Villatte, a mixed-race commander. Villatte was somewhat racist towards black soldiers. He planned to join André Rigaud and overthrow the French General Laveaux. In 1796, Villatte said the French were planning to bring back slavery.

On March 20, Villatte captured Governor Laveaux and named himself Governor. Louverture's troops quickly arrived to rescue Laveaux and drive Villatte out. Louverture opened the warehouses to the public. This showed there were no chains, which people feared meant slavery was returning. Two months later, Louverture was promoted to commander of the West Province. In 1797, he became Saint-Domingue's highest-ranking officer. Laveaux called Louverture his Lieutenant Governor. He said he would do nothing without Louverture's approval. Louverture replied, "After God, Laveaux."

Dealing with French Officials

A few weeks after Louverture's victory over Villatte, new French officials arrived. One was Sonthonax, who had declared slavery abolished. At first, Louverture and Sonthonax got along well. Sonthonax promoted Louverture to general. He also arranged for Louverture's sons, Placide and Isaac, to go to school in France. This was for their education. But it also meant they could be used as political hostages if Louverture went against France. Despite this, Placide and Isaac often ran away from school. They were moved to another school in Paris. There, they sometimes ate with French nobles like Joséphine de Beauharnais, who later married Napoleon.

In September 1796, elections were held for colonial representatives. Louverture encouraged Laveaux to run. Sonthonax was also elected. Laveaux left Saint-Domingue in October, but Sonthonax stayed. Sonthonax was a strong revolutionary and believed in racial equality. He soon became as popular as Louverture. They had similar goals but disagreed on some things. Louverture said, "I am black, but I have the soul of a white man." He meant he was loyal to France and Catholicism. Sonthonax, who had married a free black woman, said, "I am white, but I have the soul of a black man." He meant he strongly supported ending slavery and republican ideas.

They disagreed about white planters who had fled Saint-Domingue. Sonthonax saw them as enemies. Louverture saw them as people who could help the colony's economy. Their connections to France could also improve ties with Europe.

In summer 1797, Louverture allowed Bayon de Libertat, his former overseer, to return. Sonthonax threatened Louverture and ordered de Libertat to leave. Louverture wrote directly to the French government for permission for de Libertat to stay. A few weeks later, he started planning for Sonthonax to return to France. Louverture had reasons to want Sonthonax gone. He said Sonthonax tried to involve him in a plan to make Saint-Domingue independent. This plan included killing all the white people. This accusation played on Sonthonax's strong views against rich white people.

When Sonthonax reached France, he accused Louverture of being a royalist and wanting independence. Louverture knew the French government might suspect him of wanting independence. At the same time, the French government was less revolutionary. People worried it might bring back slavery. In November 1797, Louverture wrote to the French government. He assured them of his loyalty but firmly said that slavery must stay abolished.

Agreements with Britain and the United States

For months, Louverture was in charge of French Saint-Domingue. Only General André Rigaud in the south did not accept his authority. Both generals continued to fight the British. The British position on Saint-Domingue was getting weaker. Louverture was talking about their withdrawal when a new French official, Gabriel Hédouville, arrived in March 1798. He was ordered to weaken Louverture's power. By the end of the revolution, Louverture became very rich. He owned many properties and earned a lot of money each year. This made him the richest person in Saint-Domingue.

On April 30, 1798, Louverture signed a treaty with British general Thomas Maitland. The British troops would leave western Saint-Domingue. In return, French counter-revolutionaries in those areas would be forgiven. In May, Port-au-Prince returned to French rule.

In July, Louverture and Rigaud met Hédouville. Hédouville favored Rigaud, hoping to create a rivalry to reduce Louverture's power. But General Maitland also worked directly with Louverture, ignoring Hédouville. In August, Louverture and Maitland signed treaties for the British troops to leave. On August 31, they signed a secret treaty. This lifted the British blockade on Saint-Domingue. In return, Louverture promised not to cause trouble in British colonies.

Louverture's relationship with Hédouville worsened. An uprising began among the troops of Louverture's nephew, Hyacinthe Moïse. Hédouville tried to fix it, but made it worse. Louverture refused to help him. As the rebellion grew, Hédouville prepared to leave. Louverture and Dessalines threatened to arrest him. Hédouville sailed for France in October 1798. He officially gave his authority to Rigaud. But Louverture decided to work with Phillipe Roume, another French official. Louverture kept saying he was loyal to France. But he had forced out a second French official. He was also about to make a deal with one of France's enemies.

The United States had stopped trade with France in 1798. This was because of tensions over privateering (private ships attacking other ships). This was called the "Quasi"-War. But trade between Saint-Domingue and the United States was good for both sides. With Hédouville gone, Louverture sent a diplomat, Joseph Bunel, to talk with the administration of John Adams. Adams was against slavery and more sympathetic to Haiti. The treaty was similar to the one with the British. But Louverture kept refusing to declare independence. As long as France kept slavery abolished, he seemed happy for the colony to stay French in name.

Expanding Control

In 1799, tensions between Louverture and Rigaud became very high. Louverture accused Rigaud of trying to kill him to gain power. Rigaud claimed Louverture was working with the British to bring back slavery. This conflict was made worse by racial tensions between black people and mixed-race people. Louverture also wanted to remove Rigaud for political reasons. He needed to control every port to stop French troops from landing if needed.

After Rigaud's troops took border towns in June 1799, Louverture convinced Roume to declare Rigaud a traitor. Louverture then attacked the southern state. This civil war was called the War of Knives. It lasted over a year. Rigaud was defeated and fled to Guadeloupe, then France, in August 1800. Louverture let his lieutenant, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, lead most of the fighting. Dessalines became known for killing mixed-race captives and civilians.

In November 1799, during the civil war, Napoleon Bonaparte took power in France. He made a new constitution that said colonies would have special laws. The colonies feared this meant slavery would return. But Napoleon first confirmed Louverture's position and promised to keep slavery abolished. But he also told Louverture not to invade Spanish Santo Domingo. This would give Louverture a strong defensive position. Louverture decided to go ahead anyway. He forced Roume to give him permission. At the same time, Louverture wanted to improve relations with other European powers. He helped the British by telling them about a plot to start another slave revolt in British Jamaica.

In January 1801, Louverture and his nephew, General Hyacinthe Moïse, invaded the Spanish territory. They took control from the governor easily. This area was less developed than the French part. Louverture brought it under French law, ended slavery, and started modernizing it. He now controlled the entire island.

The 1801 Constitution

Napoleon had told Saint-Domingue that France would write a new constitution for its colonies. This meant they would have special laws. Despite Napoleon's promises, the former slaves feared he might bring back slavery. In March 1801, Louverture created a group to write a constitution for Saint-Domingue. This group was mostly white planters. He announced the Constitution on July 7, 1801. This officially gave him power over the whole island of Hispaniola. It made him governor-general for life with almost total power. He could also choose who would take over after him. But Louverture did not openly declare Saint-Domingue independent. He said in Article 1 that it was still a French colony.

Article 3 of the constitution said: "There cannot exist slaves [in Saint-Domingue], servitude is therein forever abolished. All men are born, live and die free and French." The constitution promised equal chances and treatment for all races. But it also kept Louverture's rules for forced labor and bringing in workers through the slave trade. Louverture saw himself as a loyal Christian Frenchman. He did not want to compromise Catholicism for Vodou. Vodou was the main faith among former slaves. Article 6 said that "the Catholic, Apostolic, Roman faith shall be the only publicly professed faith." This strong preference for Catholicism showed Louverture's French identity. It also showed his move away from Vodou.

Louverture gave the constitution to Colonel Charles Humbert Marie Vincent to deliver to Napoleon. Vincent was against the constitution. Several parts of the constitution were bad for France. There was no plan for French government officials. There were no trade benefits for France. And Louverture published the constitution before sending it to France. Vincent tried to give it to Napoleon, but was sent away to the island of Elba.

Louverture saw himself as French and tried to convince Napoleon of his loyalty. He wrote to Napoleon, but got no reply. Napoleon decided to send 20,000 men to Saint-Domingue. He wanted to bring back French control and possibly slavery. France had made a temporary peace with Great Britain. So, Napoleon could send his ships without them being stopped by the Royal Navy.

Leclerc's Attack

Napoleon's troops were led by his brother-in-law, General Charles Emmanuel Leclerc. Leclerc was told to take control of the island peacefully. He was to keep secret his orders to send away all black officers. Meanwhile, Louverture was getting ready to defend the island. He also made sure his troops were disciplined. This might have led to a rebellion against forced labor by his nephew, Moïse, in October 1801. This rebellion was stopped violently. So, when the French ships arrived, not everyone in Saint-Domingue supported Louverture.

In late January 1802, Leclerc asked for permission to land at Cap-Français. Christophe held him off. The Vicomte de Rochambeau suddenly attacked Fort-Liberté. This ended any chance of a peaceful solution. Christophe had written to Leclerc: "you will only enter the city of Cap, after having watched it reduced to ashes. And even upon these ashes, I will fight you."

Louverture's plan was to burn the coastal cities and plains. Then, he would retreat with his troops into the mountains. He would wait for yellow fever to weaken the French army. The biggest problem with this plan was communication. Christophe burned Cap-Français and retreated. But Paul Louverture was tricked by a false letter. He allowed the French to take Santo Domingo. Other officers believed Napoleon's peaceful message. Some tried to fight instead of burning and retreating.

Both sides were shocked by the violence. Leclerc tried to go back to a peaceful solution. Louverture's sons and their teacher were sent from France to help. They tried to give Napoleon's message to Louverture. When these talks failed, months of fighting followed.

This ended when Christophe switched sides. He seemed to believe Leclerc would not bring back slavery. He kept his general rank in the French army. General Jean-Jacques Dessalines did the same soon after. On May 6, 1802, Louverture went to Cap-Français. He agreed to accept Leclerc's authority. In return, he and his generals were forgiven. Louverture was forced to give up. He was placed under house arrest at his home in Ennery.

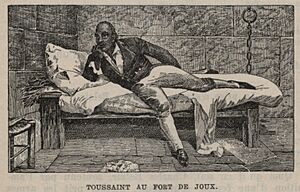

Arrest and Death

Jean-Jacques Dessalines was partly responsible for Louverture's arrest. On May 22, 1802, Dessalines learned that Louverture had not told a rebel leader to stop fighting. Dessalines immediately wrote to Leclerc to complain about Louverture. For this, Dessalines and his wife received gifts from Jean Baptiste Brunet.

Leclerc first asked Dessalines to arrest Louverture, but he refused. Jean Baptiste Brunet was ordered to do it. There are different stories about how he did it. One story says Brunet pretended he wanted Louverture's advice on managing a plantation. Louverture's own writings suggest Brunet's troops were causing trouble. This led Louverture to seek a discussion with him. Louverture had a letter from Brunet calling him a "sincere friend." Brunet was embarrassed by his trickery and was not there during the arrest.

Finally, on June 7, 1802, Toussaint Louverture was captured. This was despite the promises made when he surrendered. About a hundred of his close friends were also captured. They were sent to France. Brunet said he suspected Louverture was planning another uprising. When he boarded the ship, Toussaint Louverture warned his captors. He said, "In overthrowing me you have cut down in Saint Domingue only the trunk of the tree of liberty; it will spring up again from the roots, for they are numerous and they are deep."

The ships reached France on July 2, 1802. On August 25, Louverture was put in prison at Fort de Joux in Doubs. While there, Louverture wrote his life story. He died in prison on April 7, 1803, at age 59. People think he died from exhaustion, malnutrition, or illness like pneumonia or tuberculosis.

Beliefs and Legacy

Religion and Faith

Throughout his life, Louverture was a strong Roman Catholic. He was baptized as a slave by the Jesuits. He was one of the few slaves on the Bréda plantation who was very religious. He went to Mass every day if possible. He often served as godfather at slave baptisms. He also often tested others on their church teachings. In 1763, the Jesuits were removed for spreading Catholicism among slaves. Toussaint became closer to the Capuchin Order that followed them. He had two formal Catholic weddings after he was freed. In his writings, he remembered his family's Sunday ritual of going to church and having a meal together.

After defeating forces led by André Rigaud in the War of the Knives, Louverture gained more power. He made a new constitution for the colony in 1801. It made Catholicism the official religion. Vodou was practiced in Saint-Domingue along with Catholicism. But it is not clear if Louverture had any connection to it. As ruler, he officially discouraged Vodou and even punished its followers.

Some historians think he was a high-ranking member of the Masonic Lodge. This is based on a Masonic symbol in his signature. But because he was a strong Catholic, this is unlikely. The Pope had banned Catholics from joining Masonic groups since 1738.

Lasting Impact

After Louverture's arrest, Jean-Jacques Dessalines led the Haitian rebellion. He finally defeated the French forces in 1803. The French army was greatly weakened by yellow fever. Two-thirds of their men died before Napoleon pulled them out.

John Brown said Louverture influenced his plans to invade Harpers Ferry. In the 1800s, African Americans looked to Louverture as an example of how to gain freedom.

On August 29, 1954, the Haitian ambassador to France opened a stone cross memorial for Toussaint Louverture. It is at the Fort de Joux. Years later, the French government gave a shovelful of soil from Fort de Joux to the Haitian government. This was a symbolic transfer of Louverture's remains. In 1998, an inscription in his memory was placed on the wall of the Panthéon in Paris.

See also

In Spanish: Toussaint Louverture para niños

In Spanish: Toussaint Louverture para niños