French Revolutionary Army facts for kids

Quick facts for kids French Revolutionary Army |

|

|---|---|

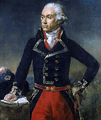

General Dampierre leading the French troops at the Battle of Jemmapes, November 1792, in an early 20th-century painting by Raymond Desvarreux

|

|

| Active | 1792–1804 |

| Country | French Republic, and European émigré groups. |

| Allegiance | |

| Motto(s) | Honneur et Patrie |

| Colors | |

| Engagements | War of the First Coalition War of the Second Coalition |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Napoleon Bonaparte Pierre Augereau Auguste Marie Henri Picot de Dampierre Louis Desaix Thomas-Alexandre Dumas Lazare Hoche Jean-Baptiste Jourdan François Christophe de Kellermann Jean-Baptiste Kléber Jean Lannes François Joseph Lefebvre André Masséna Jean Victor Marie Moreau Jean-Mathieu-Philibert Sérurier Joseph Souham |

The French Revolutionary Army (which means Armée révolutionnaire française in French) was the army of France during the French Revolutionary Wars. These wars lasted from 1792 to 1804. This army was known for its strong belief in the revolution, its large size, and sometimes its lack of good equipment.

At first, the army faced tough defeats. But soon, these revolutionary soldiers pushed foreign armies out of France. They then took over many nearby countries, setting up new governments that supported France. Famous generals like Napoleon Bonaparte, Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, and André Masséna led these armies.

It's important not to confuse the "French Revolutionary Army" with other groups called "revolutionary armies." Those were special armed groups formed during a time of great change in France called the Reign of Terror. After 1804, when France became an empire, the Revolutionary Army changed its name to the Imperial Army.

Contents

How the Army Was Formed

Before the revolution, France was ruled by kings. This time was called the Ancien Régime. But then, France changed to a constitutional monarchy and later became a republic. This happened between 1789 and 1792. The whole country changed to follow the ideas of "Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity" (Freedom, Equality, and Brotherhood).

Other countries in Europe did not like these changes, especially after the French king was executed. Countries like Austria and Prussia signed an agreement called the Declaration of Pillnitz. France then declared war. This meant that from the very start, the new French Republic needed a strong army to survive. So, one of the first things France changed was its military.

Most of the officers in the old French Royal Army came from rich, noble families. Before the king was overthrown, many of these officers left France. They joined armies that wanted to bring back the king. For example, between September and December 1791, over 2,000 officers fled France. Many who stayed were put in prison or killed during the Reign of Terror. The few officers who remained from the old army were quickly promoted. This meant that most Revolutionary officers were much younger than their enemies.

People were very excited about the revolution and wanted to protect the new government. This led to many volunteers joining the army. These new soldiers were enthusiastic but often lacked training and discipline. They were called sans-culottes because they wore long pants like peasants, not the fancy knee-breeches worn by other armies. France desperately needed soldiers, so these men quickly joined the army.

One key reason the French Revolutionary Army succeeded was a plan called "amalgamation" (amalgame). This idea came from a military planner named Lazare Carnot. He later became Napoleon's Minister of War. Carnot put young, eager volunteers and old, experienced soldiers from the former royal army into the same regiments. This way, the new soldiers learned from the veterans.

The biggest change was in the officers. Before the revolution, 90% of officers were nobles. By 1794, only 3% were nobles. Revolutionary spirit was high. The government in Paris watched the generals closely. Some generals left the army, and others were removed or executed. The government wanted soldiers to be loyal to Paris, not just to their generals.

Early Challenges and Victories

France attacked first, invading the Austrian Netherlands. But this attack quickly went wrong. The new French soldiers were not well organized and didn't always follow orders. In one case, soldiers killed their general to avoid a fight. In another, they voted on whether to follow their commander's orders. The French army had to retreat from the Austrian Netherlands.

In August 1792, a large army from Austria and Prussia, led by the Duke of Brunswick, crossed into France. They wanted to put King Louis XVI back in full power. Several French armies were easily beaten by these professional soldiers. This led to a mob attacking the king's palace in Paris and the king being overthrown.

The invading army kept advancing, and by mid-September, it looked like Paris would fall. The French government ordered the remaining armies to join together under Generals Dumouriez and François Christophe Kellermann. At the Battle of Valmy on September 20, 1792, the French army stopped Brunswick's advance. The invading army then retreated all the way back to the border. Much of this victory was thanks to the French artillery (cannons), which was considered the best in Europe.

The Battle of Valmy made other countries respect the Revolutionary armies. For the next ten years, these armies not only defended the new First French Republic, but they also expanded France's borders. They did this under leaders like Moreau, Jourdan, Kléber, Desaix, and Bonaparte.

Lazare Carnot and the Levée en Masse

The victory at Valmy saved France for a time. But in January 1793, King Louis XVI was executed. The French government also announced it would "export the revolution" to other countries. This made France's enemies even more determined to destroy the Republic and bring back a monarchy.

In early 1793, a group of countries called the First Coalition formed against France. This included Prussia, Austria, Sardinia, Naples, the Dutch Republic, Spain, and Great Britain. France was attacked from many sides. Also, a revolt broke out in a strongly Catholic region of France called La Vendée. The Revolutionary army was spread too thin, and it seemed the Republic might fall.

In early 1793, Lazare Carnot, a smart mathematician and politician, joined the Committee of Public Safety. Carnot was very good at organizing and making sure people followed rules. He began to fix the disorganized Revolutionary Armies. He realized that France's enemies had far more soldiers. So, on February 24, 1793, Carnot ordered every part of France to provide a certain number of new soldiers. This brought in about 300,000 new recruits. By mid-1793, the Revolutionary Army had grown to about 645,000 men.

On August 23, 1793, Carnot pushed for a huge call-up of all citizens, known as the levée en masse. This order said: "From this moment until such time as its enemies shall have been driven from the soil of the Republic all Frenchmen are in permanent requisition for the services of the armies. The young men shall fight; the married men shall forge arms and transport provisions; the women shall make tents and clothes and shall serve in the hospitals; the children shall turn linen into lint; the old men shall betake themselves to the public squares in order to arouse the courage of the warriors and preach hatred of kings and the unity of the Republic"

This meant that all unmarried, healthy men aged 18 to 25 had to join the army right away. Married men, women, and children had to help by making weapons, supplies, tents, and caring for the wounded. Older men were to encourage the soldiers and spread revolutionary ideas.

This order greatly increased the size of the Revolutionary Armies. It gave them enough soldiers to fight off enemy attacks. Carnot was praised by the government as the "Organizer of Victory." By September 1794, the Revolutionary Army had 1,500,000 men! Carnot's levée en masse provided so many soldiers that it wasn't needed again until 1797.

Tactics and Formations

Early on, the French army tried to follow old rules from 1791. These rules were for well-trained soldiers and officers, which the new Revolutionary Army didn't have. So, these early attempts often failed.

Commanders soon realized they needed new ways to fight. They started using ideas that had been discussed before the revolution. The final system used by the early Revolutionary Armies worked like this:

- Skirmishers: Soldiers who were very brave or skilled became skirmishers. They fought in small groups in front of the main army. They used hit-and-run tactics, like guerrilla warfare. They would hide, shoot at enemy formations, and set up ambushes. Since the enemy couldn't easily fight back against these scattered skirmishers, their morale and organization slowly broke down. This constant harassment often made a part of the enemy line weak.

- Battalion Columns: After the skirmishers had done their work, the main part of the army, made of less skilled soldiers, would attack. They formed into thick columns. These columns were easy to form and train for. They acted like powerful "battering rams" to break through the weakened enemy lines. The skirmishers also protected these columns as they advanced.

Infantry (Foot Soldiers)

After the old royal government was gone, the army stopped using named regiments. Instead, the new army was organized into numbered demi-brigades. These groups had two or three battalions. They were called demi-brigades to avoid sounding like the old royal regiments. By mid-1793, the Revolutionary Army had 196 infantry demi-brigades.

At first, the volunteer battalions didn't perform well. So, Carnot ordered that each demi-brigade should have one battalion of regular soldiers (from the old Royal Army) and two battalions of new volunteers. This mix of experienced soldiers and enthusiastic new recruits worked well. It was proven successful at Valmy in September 1792. By 1794, this new demi-brigade system was used everywhere.

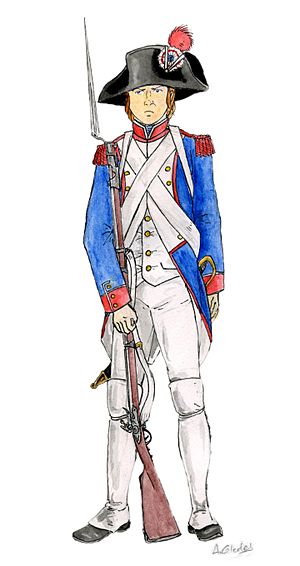

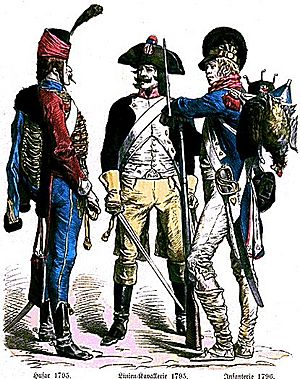

The Revolutionary Army was made up of many different types of units, so they didn't have a uniform look. Veterans wore their old white uniforms, while national guardsmen wore blue jackets. New volunteers often wore their own civilian clothes. The only thing all soldiers wore was the red Phrygian cap and the tricolor cockade (a ribbon worn on a hat) to show they were soldiers. Because supplies were low, worn-out uniforms were replaced with civilian clothes. So, the Revolutionary Army looked very mixed, except for the tricolor cockade. Later in the war, some demi-brigades got specific colored uniform jackets. For example, the French army that went to Egypt in 1798 wore purple, pink, green, red, orange, and blue jackets.

Besides uniforms, many soldiers also lacked weapons and ammunition. Any weapons captured from the enemy were immediately given to soldiers who didn't have them. After the Battle of Montenotte in 1796, 1,000 French soldiers who had gone into battle unarmed were then given captured Austrian muskets. This meant that weapons were also not uniform.

Along with the regular demi-brigades, there were also light infantry demi-brigades. These were made up of soldiers who were good at shooting. They were used for skirmishing in front of the main army. Like the line demi-brigades, the light demi-brigades also had mixed weapons and equipment.

Artillery (Cannons)

The French artillery (cannons and their crews) was very important. It was the part of the army that suffered the least when noble officers left early in the Revolution. This was because most artillery officers came from the middle class. Napoleon Bonaparte himself started as an artilleryman. Thanks to improvements made by General Jean Baptiste Vaquette de Gribeauval before the Revolution, French artillery was the best in Europe.

The Revolutionary Artillery helped win several early battles, like Valmy, 13 Vendémiaire, and Lodi. Cannons played a vital role in their success. Cannons continued to be very important on the battlefield throughout the Napoleonic Wars.

Cavalry (Horse Soldiers)

The cavalry (soldiers on horseback) was hit hard by the Revolution. Most cavalry officers were nobles and had fled France. Many French cavalrymen joined the armies fighting against the revolution. Two whole regiments, the Hussards du Saxe and the 15éme Cavalerie (Royal Allemande), even switched sides to the Austrians.

The Revolutionary Cavalry lacked trained officers, horses, and equipment. It became the worst-equipped part of the Revolutionary Army. By mid-1793, the army was supposed to have many cavalry regiments, but most were far below their full strength. However, unlike the infantry, cavalry regiments kept their original names and identities throughout the revolutionary and Napoleonic periods. For example, the Regiment de Chasseurs d'Alsace (formed in 1651) was renamed the 1er Regiment de Chasseurs in 1791 but stayed the same until it was finally disbanded after the Battle of Waterloo.

Aerostatic Corps (Balloon Force)

The French Aerostatic Corps (compagnie d'aérostiers) was the first French air force. It was created in 1794 to use balloons, mainly for reconnaissance (spying on the enemy). The first time a balloon was used in battle was on June 2, 1794. It helped scout during an enemy attack. On June 22, the corps moved the balloon to the plain of Fleurus, near the Austrian troops at Charleroi.

Famous Generals

Notable Battles and Campaigns

Active Armies (1792–1804)

Here are some of the main armies that were active during this period:

- Armies of 1792

- Armée du Nord (Army of the North)

- Armée du Rhin (Army of the Rhine)

- Armée des Alpes (Army of the Alps)

- Armée des Pyrénées (Army of the Pyrenees)

- Armée des côtes (Army of the Coasts)

- Armée du Centre (Army of the Center)

- Armée de réserve (Reserve Army)

- Armée du Var (Army of the Var)

- Armies after 1793 changes

- Armée du Nord (Army of the North)

- Armée des Ardennes (Army of the Ardennes)

- Armée de Moselle (Army of the Moselle)

- Armée du Rhin (Army of the Rhine)

- Armée des Alpes (Army of the Alps)

- Armée d'Italie (Army of Italy)

- Armée des côtes de Brest (Army of the Coasts of Brest)

- Armée des côtes de Cherbourg (Army of the Coasts of Cherbourg)

- Armée des côtes de La Rochelle (Army of the Coasts of La Rochelle)

- Armée des Pyrénées occidentales (Army of the Western Pyrenees)

- armée des Pyrénées orientales (Army of the Eastern Pyrenees)

- The Armée de la Rochelle was renamed the armée de l'Ouest (Army of the West) on October 1.

- Armies formed for special missions

- Army of Sambre-et-Meuse

- Armée de Rhin-et-Moselle (Army of Rhine and Moselle)

- Armée de Rome (Army of Rome) - Formed from the Army of Italy to take over Rome.

- Armée d'Angleterre (Army of England) - First formed to fight the British in 1797. It was later renamed Armée d'Orient (Army of the East) and split into:

- Armée de Syrie (Army of Syria)

- Armée d'Égypte (Army of Egypt)

- Saint-Domingue expedition (Saint-Domingue Expedition)

- Armée de Réserve (Reserve Army) - Formed secretly by Napoleon. He led it himself during the Italian campaign of 1800, which ended with the Battle of Marengo.

- Armée d'Allemagne (Army of Germany)

- Armée du Danube (Army of the Danube)

- Armée de Hollande (Army of Holland)

- Armée des Grisons (Army of the Grisons)

- Armée des côtes de l'Océan (Army of the Coasts of the Ocean) - This army was created to invade England. In 1805, it became La Grande Armée (The Grand Army).

See also

- Émigré armies of the French Revolutionary Wars - These were French royalist forces that fought against the Revolutionary government.

- Social background of officers and other ranks in the French Army, 1750–1815

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |