Manumission facts for kids

Manumission is when a person who is enslaved is set free by their enslaver. It's also called enfranchisement. This act of giving freedom happened in many different ways throughout history. The methods used depended on the time and place.

Historian Verene Shepherd explains that a common type was "gratuitous manumission." This means freedom was given to enslaved people by their enslavers before slavery completely ended.

People had many reasons for freeing enslaved individuals. Sometimes, it was a kind and thoughtful act. For example, a master might free a loyal servant in their will after many years of service. A trusted manager might also be freed as a thank you. However, it was less common for those working in fields or workshops to be noticed this way. Often, older enslaved people were more likely to gain their freedom.

In the early Roman Empire, laws were made to limit how many enslaved people could be freed in wills. This suggests that freeing people this way was very common back then.

Freeing enslaved people could also benefit the owner. The chance of gaining freedom encouraged enslaved people to work hard and follow rules. Roman enslaved people were sometimes paid a small amount of money (called peculium). They could save this money to buy their own freedom. Contracts found in Delphi, Greece, show the exact rules for becoming free.

Manumission wasn't always a kind or selfless act. In one story from the Arabian Nights, an enslaver threatens to free his enslaved person for lying. The enslaved person replies, "you shall not free me, for I have no skill to earn my living." This shows that being freed without a way to support oneself could be a problem.

Contents

Freedom in Ancient Greece

In Ancient Greece, there were several ways for enslaved people to become free. A master might free an enslaved person "at his death" by writing it in his will.

Rarely, enslaved people who earned enough money could buy their own freedom. These people were known as choris oikointes. Two famous bankers from the 4th century BCE, Pasion and Phormio, were once enslaved before they bought their freedom.

Sometimes, an enslaved person could be "sold" to a sanctuary. From there, a god was believed to grant them freedom. In very rare cases, a city could free an enslaved person. For example, Athens freed everyone who fought in the Battle of Arginusae in 406 BCE.

Even after being freed, an enslaved person usually could not become a citizen. Instead, they became a metic, which was a resident foreigner. The former master became their prostatès, a kind of guardian. The freed person might still have duties to their former master. They were often required to live near them (this was called paramone). If they broke these rules, they could face punishment or even be enslaved again. Sometimes, extra payments could free them from these duties. However, former enslaved people could own property, and their children were born completely free.

Freedom in Ancient Rome

Under Roman law, an enslaved person was seen as property, not as a person with rights. In Ancient Rome, an enslaved person who was freed was called a libertus (or liberta for a female). They became a citizen. Manumissions were also taxed.

The soft felt pileus hat was a symbol of freedom for enslaved people. Enslaved people were not allowed to wear them.

The Romans believed this hat meant liberty. When an enslaved person gained freedom, they would shave their head and wear an undyed pileus. This is why the phrase servos ad pileum vocare meant "to call enslaved people to the hat." It was a call to freedom, often used to encourage enslaved people to join the army with the promise of liberty. The goddess of freedom, Libertas, was often shown holding this cap.

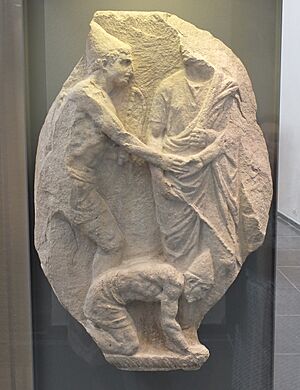

The cap was also linked to a special rod called a vindicta or festuca. This rod was used in a ceremony called manumissio vindicta, which means "freedom by the rod."

In this ceremony, the master brought the enslaved person before a magistratus (a Roman official). The master explained why they wanted to free the person. The official's assistant would touch the enslaved person's head with the rod. He would say formal words declaring the person free. The master would hold the enslaved person, say "I want this person to be free," then turn them around and let them go. The official would then declare them free.

A freed person usually took their former owner's family name. The former owner became their patron, and the freed person became their client. This meant they had certain duties to their former master, who also had duties to them. A freed person could even have several patrons.

A freed enslaved person became a citizen. However, not all citizens had the same rights. For example, women could become citizens, but they did not have the same protections or rights as men. They could not vote or hold public office.

The rights of freed enslaved people were limited by specific laws. A freed male could become a civil servant but could not hold higher government positions. They also could not serve as priests of the emperor or other highly respected public roles.

However, if they were good at business, freedmen could become very wealthy. Their children had full legal rights. Famous Romans who were the sons of freedmen include the poet Horace and the emperor Pertinax.

A well-known freedman in Latin literature is Trimalchio. He is a character in the Satyricon by Petronius who shows off his new wealth.

Freedom in Peru

In colonial Peru, laws about manumission were based on the Siete Partidas, a Spanish law code. This code said that masters who freed their enslaved people should be respected by them for giving such a generous gift.

Like in other parts of Latin America, enslaved people could buy their freedom. This was done by agreeing on a price with their master, a system called coartación. This was the most common way for enslaved people to become free. Manumission also happened during baptism or as part of an owner's last will.

In baptismal manumission, enslaved children were freed at their baptism. Many of these freedoms came with conditions, like serving the owner until the owner died. Children freed at baptism were often the children of parents who were still enslaved. A child freed at baptism but still living with enslaved family was more likely to be enslaved again. Baptismal manumission could be used as proof of freedom in court, but it didn't always have enough information to be a full carta de libertad (freedom paper).

Female enslavers were more likely than males to free their enslaved people at baptism. Women often used phrases like "for the love I have for her" to explain why they were freeing their enslaved people. Male enslavers were much less likely to use such personal reasons.

Many children freed at baptism were likely the children of their male owners, though this is hard to prove. Owners often said these freedoms were due to their kindness. However, records show that parents or godparents sometimes paid to ensure the child's freedom. Mothers were almost never freed at the same time as their children, even if they had the owner's children. Freeing an enslaved person's children at baptism could be a way for owners to keep the loyalty of the children's enslaved parents.

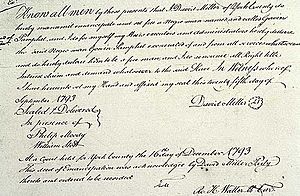

Enslaved people could also be freed in an owner's last will. This was called testamentary manumission. Owners often expressed affection for the enslaved person as a reason for freeing them. They also often said they wanted to die with a clear conscience.

Heirs sometimes tried to challenge these wills, claiming fraud or that the enslaved person had taken advantage of a sick relative. However, courts usually upheld testamentary manumissions. They saw enslaved people as part of the owner's property to be given away as they wished. Relatives who claimed fraud had to provide strong proof, or their claims would be dismissed. Like with baptismal manumission, conditions of service were sometimes placed on the freed person, like caring for another relative.

In Spanish-American law, a person could decide what happened to one-fifth of their property. The rest went to children, spouses, and other relatives. An enslaved person could be sold to cover debts of the estate. But this was not allowed if they had already paid part of their price towards freedom, as this was a legal agreement. As long as a person did not disinherit their children or spouse, an enslaver could free their enslaved people as they wished.

Freedom in the Caribbean

Manumission laws were different in various Caribbean colonies. For example, the island of Barbados had very strict laws. Owners had to pay £200 for male enslaved people and £300 for female enslaved people. They also had to explain their reasons to the authorities. In some other colonies, there were no fees.

It was common for former enslaved people to buy their family members or friends to free them. For instance, Susannah Ostrehan became a successful businesswoman in Barbados. She bought and freed many of her acquaintances.

In Jamaica, manumission was not very regulated until the 1770s. After that, people freeing enslaved individuals had to pay a bond. This was to make sure the freed people did not become a burden on the local community. One study of Jamaica's manumission records shows that freeing enslaved people was quite rare around 1770. Only about 165 enslaved people gained freedom this way. While manumission didn't greatly change the total enslaved population, it was important for the growth of the free population of color in Jamaica in the late 1700s.

Freedom in the United States

In the North American colonies, African enslaved people were freed as early as the 1600s. Some, like Anthony Johnson, even became landowners and enslavers themselves. Enslaved people could sometimes arrange to buy their own freedom by paying their master an agreed amount. Some masters asked for market prices, while others set a lower price because of the enslaved person's service.

Rules for manumission began in 1692. Virginia required that to free an enslaved person, the owner had to pay for them to be sent out of the colony. A 1723 law said that enslaved people could not be freed "for any reason whatsoever." The only exception was for "meritorious services" approved by the governor and council.

Sometimes, a master drafted into the army would send an enslaved person instead. They promised freedom if the enslaved person survived the war. The new government of Virginia changed these laws in 1782. They declared freedom for enslaved people who had fought for the colonies during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). The 1782 laws also allowed masters to free their enslaved people on their own. Before this, freeing an enslaved person needed permission from the state legislature, which was very hard to get.

However, as the number of free Black people grew, Virginia passed new laws. In 1778, they forbade free Black people from moving into the state. In 1806, they required newly freed enslaved people to leave within one year unless they had special permission.

In the Upper South in the late 1700s, plantation owners needed fewer enslaved people. This was because they switched from growing tobacco, which needed a lot of labor, to mixed-crop farming. States like Virginia made it easier for enslavers to free their enslaved people. In the 20 years after the American Revolutionary War, so many enslavers freed people in wills or by deed. The number of free Black people in the Upper South rose from less than 1% to 10% of the total Black population. In Virginia, the percentage of free Black people went from 1% in 1782 to 7% in 1800.

Along with several Northern states ending slavery during this time, the percentage of free Black people across the country grew to about 14% of the total Black population. New York and New Jersey passed laws for gradual abolition. These laws kept the free children of enslaved people as indentured servants until their twenties.

After the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, new areas for growing cotton opened up. This led to a greater demand for enslaved labor. As a result, the number of manumissions decreased. In the 1800s, slave revolts like the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) and especially Nat Turner's rebellion in 1831, made enslavers more fearful. Most Southern states then passed laws making manumission almost impossible. This continued until the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was passed in 1865. This amendment abolished slavery after the American Civil War, "except as a punishment for crime." In South Carolina, freeing an enslaved person needed permission from the state legislature. Florida law completely banned manumission.

Of the Founding Fathers of the United States, the Southerners were major enslavers. Northerners also held enslaved people, usually fewer, as domestic servants. John Adams owned none. George Washington freed his own enslaved people in his will. His wife, however, independently held many enslaved people. Thomas Jefferson freed five enslaved people in his will. The remaining 130 were sold to pay his debts. James Madison did not free his enslaved people. Some were sold to pay debts, but his widow and son kept most to work the Montpelier plantation.

Alexander Hamilton's slave ownership is not clear. It is likely he supported abolition, as he was an officer of the New York Manumission Society. John Jay founded this society and freed his domestic enslaved people in 1798. That same year, as Governor of New York, he signed the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery. John Dickinson freed his enslaved people between 1776 and 1786. He was the only Founding Father to do so during that period.

Freedom in the Ottoman Empire

Slavery in the Ottoman Empire became less important to Ottoman society in the late 1800s and early 1900s. In the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire started to limit the slave trade. This was due to pressure from European countries. The slave trade had been legal under Ottoman law since the empire began.

Ottoman policy encouraged freeing male enslaved people, but not female enslaved people. The number of enslaved people traded in the Islamic empire over centuries shows this. There were roughly two female enslaved people for every male.

The Ottoman Empire and 16 other countries signed the 1890 Brussels Conference Act. This act aimed to stop the slave trade. However, secret slavery continued well into the 20th century. Groups were even formed to illegally bring in enslaved people. Slave raids and taking women and children as "spoils of war" decreased but did not stop entirely. This happened despite public denials, such as the enslavement of girls during the Armenian Genocide. Armenian girls were sold as enslaved people during the Armenian genocide of 1915. Turkey did not officially agree to the 1926 League of Nations convention on stopping slavery until 1933. However, illegal sales of girls were still reported in the 1930s. Laws specifically banning slavery were passed in 1964.

See also

In Spanish: Manumisión para niños

In Spanish: Manumisión para niños

- Emancipation

- Islamic views on slavery

- Mukataba

- Netto Question

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |