John Jay facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Jay

|

|

|---|---|

John Jay, by Gilbert Stuart, 1794

|

|

| 1st Chief Justice of the United States | |

| In office October 19, 1789 – June 29, 1795 |

|

| Nominated by | George Washington |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | John Rutledge |

| 2nd Governor of New York | |

| In office July 1, 1795 – June 30, 1801 |

|

| Lieutenant | Stephen Van Rensselaer |

| Preceded by | George Clinton |

| Succeeded by | George Clinton |

| Acting United States Secretary of State | |

| In office September 15, 1789 – March 22, 1790 |

|

| President | George Washington |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| United States Secretary of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office July 27, 1789 – September 15, 1789 Acting |

|

| President | George Washington |

| Preceded by | Himself |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| In office December 21, 1784 – March 3, 1789 |

|

| Appointed by | Congress of the Confederation |

| Preceded by | Robert R. Livingston |

| Succeeded by | Himself |

| United States Minister to Spain | |

| In office September 27, 1779 – May 20, 1782 |

|

| Appointed by | Second Continental Congress |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | William Short |

| 6th President of the Continental Congress | |

| In office December 10, 1778 – September 28, 1779 |

|

| Preceded by | Henry Laurens |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Huntington |

| Delegate from New York to the Second Continental Congress | |

| In office December 7, 1778 – September 28, 1779 |

|

| Preceded by | Philip Livingston |

| Succeeded by | Robert R. Livingston |

| In office May 10, 1775 – May 22, 1776 |

|

| Preceded by | Seat established |

| Succeeded by | Seat abolished |

| Delegate from New York to the First Continental Congress | |

| In office September 5, 1774 – October 26, 1774 |

|

| Preceded by | Seat established |

| Succeeded by | Seat abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

John Jay

December 12, 1745 New York City, British America |

| Died | May 17, 1829 (aged 83) Bedford, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Federalist |

| Spouse |

Sarah Livingston

(m. 1774; died 1802) |

| Children | |

| Relatives | Jay family |

| Education | King’s College (AB, MA) |

| Signature | |

John Jay (born December 12, 1745 – died May 17, 1829) was an important American leader. He was a Founding Father of the United States. Jay helped create the new country.

He was the first Chief Justice of the United States. This is the head judge of the highest court. He also served as the second governor of New York. Jay played a big role in shaping America's foreign policy in the 1780s. He was a key leader of the Federalist Party. This party supported a strong central government.

Jay came from a wealthy family in New York City. They were merchants of French and Dutch background. He became a lawyer. He joined groups that opposed British rules. These groups helped start the American Revolution. Jay was chosen for the First Continental Congress. He also became president of the Second Continental Congress.

From 1779 to 1782, Jay was the ambassador to Spain. He convinced Spain to lend money to the new United States. He also helped negotiate the Treaty of Paris. This treaty officially ended the war. Britain recognized America's independence. After the war, Jay was the Secretary of Foreign Affairs. He managed foreign policy under the first U.S. government.

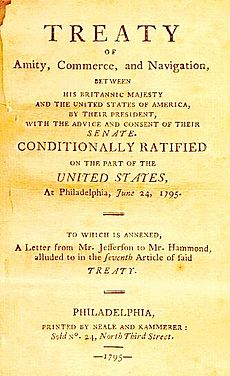

Jay believed in a strong central government. He helped get the U.S. Constitution approved in New York in 1788. He wrote five of the Federalist Papers. These essays explained why the new Constitution was a good idea. President George Washington chose Jay to be the first Chief Justice. He served from 1789 to 1795. In 1794, Jay negotiated the Jay Treaty with Britain. This treaty helped avoid another war.

Jay also served as governor of New York from 1795 to 1801. As governor, he helped pass a law to end slavery slowly in New York. He turned down another chance to be Chief Justice. He retired to his farm in Westchester County, New York.

Contents

John Jay's Early Life and Education

Family Background and Childhood

John Jay's family was well-known in New York City. They were merchants. His family came from French Protestants called Huguenots. They moved to New York to escape religious problems in France. Jay's grandfather, Auguste Jay, built a successful trading business. John's father, Peter Jay, was born in New York City in 1704. He became a rich trader in goods like furs and wheat.

Jay's mother was Mary Van Cortlandt. Her family was Dutch. She married Peter Jay in 1728. They had ten children, but only seven lived to be adults. Mary's father, Jacobus Van Cortlandt, was a mayor of New York City.

John Jay was born on December 12, 1745, in New York City. A few months later, his family moved to Rye, New York. His father had stopped working after a smallpox outbreak. Two of John's siblings became blind from the disease.

Schooling and Law Studies

Jay grew up in Rye. His mother taught him at home until he was eight. Then he went to study with a priest in New Rochelle. In 1760, when he was 14, Jay went to King's College in New York City. This college is now called Columbia College. He made many important friends there. One of his closest friends was Robert Livingston.

After graduating in 1764, Jay became a law clerk. He worked for Benjamin Kissam, a famous lawyer. In 1768, Jay became a lawyer himself. He started his own law office in 1771.

Joining Politics and the Revolution

In 1774, Jay joined the New York Committee of Correspondence. This was his first public role in the American Revolution. The committee helped organize American opposition to British rules.

Jay believed that British taxes were wrong. He thought Americans had a right to resist them. At first, he wanted to find a peaceful solution with Britain. But events like the burning of Norfolk, Virginia, by British troops made him support independence. As the American Revolutionary War began, Jay worked hard for the American cause. He helped stop those who supported Britain. He became a strong supporter of American independence. In 1780, Jay became a member of the American Philosophical Society.

John Jay's Family Life

On April 28, 1774, Jay married Sarah Van Brugh Livingston. She was the daughter of New Jersey Governor William Livingston. Sarah was seventeen and John was twenty-eight when they married. They had six children together: Peter Augustus, Susan, Maria, Ann, William, and Sarah Louisa.

Sarah traveled with Jay when he was a diplomat in Spain and Paris. They lived with Benjamin Franklin in Paris. While Jay was in Paris, his father died. This meant Jay had to take care of his blind brother and sister, Peter and Anna. His brother Augustus had mental health issues, so Jay supported him too. Another brother, Fredrick, often had money problems. Jay's brother James even joined the British side during the war. This caused problems for Jay's family.

Jay Family Homes

Jay grew up in Rye, New York. His father bought a farm there in 1745. After the Revolutionary War, Jay returned to this home. He inherited the property in 1813. He later gave it to his oldest son, Peter Augustus Jay.

Today, about 23 acres of the original property remain. This area is called the Jay Estate. The 1838 Peter Augustus Jay House stands there. It was built over the old family farmhouse. The Jay Heritage Center now cares for the site. It is used for education.

As an adult, Jay built Bedford House near Katonah, New York. He moved there in 1801 with his wife Sarah to retire. This property later went to his younger son, William Jay. New York State bought it in 1958. It is now the John Jay Homestead State Historic Site.

Both of Jay's homes are National Historic Landmarks. They are open to the public for visits.

John Jay's Views and Beliefs

Views on Slavery

The Jay family had been involved in the slave trade. John Jay himself owned slaves during his lifetime. Records show he owned at least 17 slaves. He bought, owned, and sometimes freed them. In 1783, one of his slaves tried to escape in Paris. Jay was upset by this.

Even though he owned slaves, Jay was a founder of the New York Manumission Society in 1785. This group worked to end slavery. They encouraged boycotts against businesses involved in the slave trade. They also helped free Black people with legal advice.

The Society helped pass a law in 1799 for gradual emancipation in New York. Jay signed this law as governor. This law said that children born to enslaved parents after July 4, 1799, would be free. However, they had to work for the mother's owner for many years. The law did not free people who were already enslaved before 1799. All slaves in New York were finally freed by July 4, 1827.

Jay's work against slavery was not popular everywhere. Some people in New York who still practiced slavery did not like his views. In 1794, during talks with Britain, Jay upset many Southern slave owners. He did not demand payment for slaves who had been freed by the British during the Revolution.

Religious Beliefs

John Jay was a member of the Church of England. After the American Revolution, he joined the Protestant Episcopal Church. He was a leader at Trinity Church in New York.

Jay believed that Christian teachings were important for good government. He wrote that "our Christian nation" should choose Christians as their leaders. He also said that no society could have order and freedom without the moral rules of Christianity. Jay was also a leader of the American Bible Society.

John Jay During the American Revolution

Jay was chosen to be a delegate to the First and Second Continental Congresses. These meetings decided if the colonies should declare independence. At first, Jay wanted to make peace with Britain. He helped write the Olive Branch Petition. This letter asked the British government to work things out with the colonies.

But as war became certain, Jay supported the revolution. He backed the Declaration of Independence. Jay's ideas changed as events happened. He became a strong supporter of separating from Britain. He worked to get New York to join the cause.

In 1774, Jay returned to New York. He worked on New York City's Committee of Sixty. This group tried to stop goods from being imported from Britain. Jay was also elected to the New York Provincial Congress. He helped write the first Constitution of New York, 1777. Because of these duties, he could not vote on or sign the Declaration of Independence.

Jay also served on the New York Committee to Detect and Defeat Conspiracies. This group watched and fought against people who supported Britain. In 1777, Jay became the Chief Justice of the New York Supreme Court. He served there for two years.

The Continental Congress chose Jay to be its president. He served from December 10, 1778, to September 28, 1779. This was mostly an honorary position. It showed the strong will of the Congress.

John Jay as a Diplomat

Minister to Spain

On September 27, 1779, Jay was sent to Spain as a diplomat. His job was to get money, trade agreements, and recognition of American independence. The Spanish king and queen did not officially accept Jay as the U.S. Minister. They did not want to recognize American independence until 1783. They worried it might cause revolutions in their own colonies. However, Jay did convince Spain to lend $170,000 to the U.S. government. He left Spain on May 20, 1782.

Peace Negotiator

On June 23, 1782, Jay arrived in Paris. This is where talks to end the American Revolutionary War would happen. Benjamin Franklin was the most experienced diplomat there. Jay wanted to learn from him. The United States decided to negotiate with Britain first, then with France.

In July 1782, Britain offered America independence. But Jay refused the offer. He said Britain must recognize American independence during the talks. This stopped the talks until the fall. The final treaty said the U.S. would have fishing rights near Newfoundland. Britain would recognize the U.S. as independent. Britain would also remove its troops. In return, the U.S. would stop taking property from British supporters. It would also honor private debts.

The treaty gave the U.S. independence. But it left many border areas unclear. Many parts of the treaty were not followed. John Adams said Jay played the most important role in these talks.

Secretary of Foreign Affairs

Jay served as the second Secretary of Foreign Affairs from 1784 to 1789. In September 1789, this department was renamed the Department of State. Jay served as acting Secretary of State until March 22, 1790.

Jay wanted to create a strong foreign policy for America. He worked to get other powerful European countries to recognize the U.S. He also wanted to create a stable American currency. He worked to pay back America's debts from the war. He tried to secure the country's borders. He also worked to protect American trade ships from pirates. Jay wanted to keep America's good reputation at home and abroad. He also worked to keep the country united under the early Articles of Confederation government.

The Federalist Papers

Jay felt he had a lot of responsibility but not enough power. So, he joined Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. They argued for a stronger government than the one under the Articles of Confederation.

Jay did not attend the Constitutional Convention. But he strongly supported creating a new, stronger, and balanced government. They wrote eighty-five articles called The Federalist Papers. They used the pen name "Publius." These articles convinced New York to approve the new Constitution of the United States. Jay wrote five of these articles. They discussed dangers from foreign countries and the Senate's role in making treaties.

The Jay Court

In September 1789, George Washington offered Jay the job of Secretary of State. Jay turned it down. Washington then offered him the position of Chief Justice of the United States. Washington called this job "the keystone of our political fabric." Jay accepted. He was confirmed by the U.S. Senate on September 26, 1789. Jay took his oath of office on October 19, 1789.

The Supreme Court's work in its first few years was mostly about setting up rules. The Justices also traveled to different courts to hear cases. There were no rules against Supreme Court Justices being involved in politics. So, Jay used his free time to help Washington's government.

Jay helped spread Washington's message of neutrality. He also reported on a French minister's efforts to get American support for France. However, Jay also showed the Court's independence. In 1790, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton asked the Court to support a law. Jay replied that the Court only ruled on whether cases were constitutional. He refused to take a side on the law.

Important Cases

The Jay Court's first case was West v. Barnes (1791). The Court decided this case based on rules, not on whether the law was constitutional.

In Hayburn's Case (1792), the Court had to decide if a law could make courts decide if veterans deserved pensions. The Jay Court wrote to President Washington. They said this was not a "judicial nature" job. They also said the law broke the separation of powers. This is because the other branches could change the court's decision.

In Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), the Jay Court decided if states could be sued in federal court. The Court ruled that two South Carolina Loyalists could sue Georgia. Their land had been taken by Georgia. This decision caused a lot of debate. It meant old debts might have to be paid to Loyalists. This ruling was later overturned by the Eleventh Amendment. This amendment said a state cannot be sued by a citizen of another state or foreign country.

Jay Treaty with Britain

In 1794, relations with Britain were very tense. It seemed like war might break out. British goods were everywhere in the U.S. But American goods faced British trade limits. Britain still held forts in the north that they had promised to leave. Britain was also seizing American sailors and supplies meant for France.

Washington sent Jay to Britain to negotiate a new treaty. Jay was still Chief Justice at this time. In March 1795, the treaty, known as the Jay Treaty, was brought to America. The treaty ended Britain's control of its northwestern forts. It also gave the U.S. "most favored nation" status for trade. The U.S. agreed to limited trade access to the British West Indies.

The treaty did not solve all problems. It did not address American complaints about shipping rights or the seizing of sailors. Many Americans, especially the Democratic-Republicans, were angry about it. But Washington supported the treaty. The Senate approved it by a 20–10 vote. This was exactly the two-thirds majority needed.

People who opposed the treaty were very angry. Jay was criticized by protesters. He even joked that he could travel from Boston to Philadelphia at night just by the light of burning effigies (dolls made to look like him).

Governor of New York

While in Britain, Jay was elected the second governor of New York in May 1795. He took over from George Clinton. He resigned from the Supreme Court on June 29, 1795. He served as governor for six years until 1801.

As governor, he received a suggestion from Hamilton to change voting districts for political reasons. Jay wrote on the letter that it was a "measure for party purposes which it would not become me to adopt." He did not reply.

President John Adams later nominated Jay to be Chief Justice again. The Senate quickly approved him. But Jay declined the job. He said he was not in good health. He also felt the court did not have enough "energy, weight and dignity." After Jay said no, Adams successfully nominated John Marshall as Chief Justice.

Retirement and Death

In 1801, Jay turned down another chance to be governor. He also declined to return as Chief Justice. He retired to his farm in Westchester County, New York. Soon after, his wife died. Jay stayed healthy and continued farming. He mostly stayed out of politics. In 1819, he wrote a letter against Missouri becoming a slave state. He said slavery "ought not to be introduced nor permitted in any of the new states."

On May 14, 1829, Jay had a stroke. He lived for three more days, dying on May 17 in Bedford, New York. He was the last surviving President of the Continental Congress. Jay chose to be buried in Rye, where he grew up. He had moved his wife's remains and those of his ancestors to a private cemetery there in 1807. The Jay Cemetery is still maintained by his family. It is the oldest active cemetery connected to a figure from the American Revolution.

John Jay's Legacy

Places Named After Jay

Many places in his home state of New York are named after him. These include Fort Jay on Governors Island and John Jay Park in Manhattan. Other places named for him are the towns of Jay in Maine, New York, and Vermont. Also, Jay County, Indiana is named for him. Mount John Jay on the border of Alaska and Canada is named after him. So is Jay Peak in Vermont.

Schools and Universities

The John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City was renamed for Jay in 1964.

At Columbia University, excellent students are called John Jay Scholars. One of the dorms there is called John Jay Hall. The university also gives out the John Jay Awards to outstanding graduates.

In Pittsburgh, the John Jay Center houses part of Robert Morris University.

High schools named after Jay include:

- John Jay Educational Campus (Brooklyn, New York)

- John Jay High School (Cross River, New York)

- John Jay High School (Hopewell Junction, New York)

- John Jay High School (San Antonio, Texas)

The John Jay Institute near Philadelphia prepares leaders for public service.

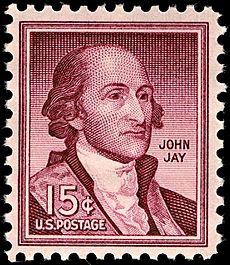

Postage Stamps

In Jay's hometown of Rye, New York, the post office issued a special stamp on September 5, 1936. A mural called John Jay at His Home was painted for the post office lobby in 1938.

On December 12, 1958, the United States Postal Service released a 15¢ postage stamp honoring Jay.

Jay's Papers

The Selected Papers of John Jay is a project by scholars at Columbia University. They are collecting and publishing letters written by and to Jay. These documents show his many contributions to building the nation. More than 13,000 documents have been gathered. Some of Jay's papers are available online through the National Archives.

In Popular Culture

John Jay's childhood home in Rye was featured in the novel The Spy by James Fenimore Cooper. This book was about spies during the Revolutionary War. It was based on a story Jay told Cooper about his own experiences.

John Jay has been played by actors in TV shows. Tim Moyer played him in the 1984 miniseries George Washington. Nicholas Kepros played him in the 1986 sequel, George Washington II: The Forging of a Nation.

Notable Descendants

Jay had six children. These included Peter Augustus Jay and William Jay, who worked to end slavery. Later generations of his family included doctors, lawyers, diplomats, and writers. One descendant was Mary Rutherfurd Jay, a horticulturalist. Another was Adam von Trott zu Solz, who fought against Nazism.

See also

In Spanish: John Jay para niños

In Spanish: John Jay para niños

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of abolitionist forerunners

- List of United States Supreme Court cases prior to the Marshall Court

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |