Free Negro facts for kids

In the British colonies in North America and later in the United States, before slavery was ended in 1865, a free Negro or free Black was an African American who was not enslaved. This term included people who had been freed from slavery (called freedmen) and those who were born free (called free people of color).

In South Africa between 1652 and 1840, a "free black" was a person of color who had been freed from slavery. People of color could be "free black," "free burgher" (freeborn citizens), "slave," or "freeborn people" (native people).

In the Netherlands in the 1600s, free black men often married white women. There were no laws against mixed-race marriages.

Contents

Background of Free Black People

Slavery was legal in all European colonies in North America at different times. Not all Africans who came to America were enslaved. Some came as free men, like sailors. In the early colonial years, some Africans came as indentured servants. This meant they worked for a set number of years to pay off their travel debt, then they became free. Many European immigrants also came this way.

By 1678, there were already free black people in North America.

Many different groups helped the free black population grow:

- Children born to free black women.

- Children born to white indentured servants or free white women, who were also free.

- Mixed-race children born to free Native American women.

- Slaves who were freed by their owners.

- Slaves who escaped from their enslavers.

- Descendants of free black people who were never enslaved.

Black labor was very important for growing tobacco in Virginia and Maryland. It was also important for growing rice and indigo in South Carolina. Between 1620 and 1780, about 287,000 enslaved people were brought to the Thirteen Colonies. This was about 5% of the more than six million enslaved people brought from Africa. Most enslaved Africans were sent to sugar-producing colonies in the Caribbean and to Brazil.

| Years | Number |

|---|---|

| 1620–1700 | 21,000 |

| 1701–1760 | 189,000 |

| 1761–1770 | 63,000 |

| 1771–1780 | 15,000 |

| Total | 287,000 |

Enslaved people lived longer in the Thirteen Colonies than in Latin America or the Caribbean. This, along with a high birth rate, meant the number of enslaved people grew quickly. By 1860, there were nearly 4 million enslaved people in the U.S.

The Southern Colonies (Maryland, Virginia, and Carolina) brought in more enslaved people. They quickly made laws that defined slavery as a racial group linked to African heritage. In 1663, Virginia made a law called partus sequitur ventrem. This meant that children were born with the same status as their mother. So, if a mother was enslaved, her child was also enslaved, no matter who the father was. Other colonies soon made similar laws.

Many free black families in the Thirteen Colonies before the American Revolution came from relationships between white women and African men. These relationships often happened among working-class people. Because the children were born to free women, they were also free.

Slave owners freed slaves for different reasons. They might reward long service, or heirs might not want to own slaves. Some freed enslaved women and their children. Enslaved people could sometimes buy their freedom. They might save money from working for others. In the mid-to-late 1700s, Methodist and Baptist preachers encouraged slave owners to free their slaves. They believed all people were equal before God.

Before the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), few enslaved people were freed. About 30,000 free African Americans lived in Colonial America just before the war. This was about 5% of all African Americans. Most free African Americans were of mixed race.

The American Revolution greatly changed slave societies. In 1775, the British governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, promised freedom to enslaved people who joined the British army. The American army also started allowing black people to fight, promising them freedom. Tens of thousands of enslaved people escaped during the war. After the war, the British took over 3,000 Black Loyalists and other Loyalists to Nova Scotia and Canada.

After the war, the number of free black people in the U.S. grew a lot. Northern states slowly ended slavery. Many slave owners in the Upper South also freed their slaves. From 1790 to 1810, the number of free black people in the Upper South increased. Across the country, the share of free black people among all black people rose to 13%. After 1810, growing cotton in the Deep South increased the demand for slaves. This caused the number of freed slaves to drop.

In the years before the Civil War, many enslaved people escaped to freedom in the North and Canada. They were helped by the Underground Railroad, a secret network of safe houses and routes. The 1860 census counted 488,070 "free colored" people in the United States.

Ending Slavery

Organized movements to end slavery mostly began in the mid-1700s. The ideas of the American Revolution and the Declaration of Independence inspired many black Americans. Both enslaved and free black men fought in the Revolution. In the North, enslaved people ran away during the war. In the South, some declared themselves free and joined the British.

In the 1770s, black people in New England asked their state governments for freedom. By 1800, all northern states had ended slavery or planned to do so slowly. Even when free, black people often faced fewer civil rights. They had limits on voting and faced racism, segregation, and violence. Vermont ended slavery in 1777. Massachusetts ended it in 1780. Other Northern states slowly ended slavery. New Jersey was the last original Northern state to start ending slavery in 1804.

Slavery was banned in the federal Northwest Territory in 1787. The free black population grew from 8% to 13.5% between 1790 and 1810. Most lived in the Mid-Atlantic States, New England, and the Upper South.

The rights of free black people changed as poor white men gained more power in the late 1820s and early 1830s. The National Negro Convention movement began in 1830. Black men held meetings to discuss the future of black people in America. Women like Maria Stewart and Sojourner Truth also spoke out. These efforts faced resistance as anti-black feelings grew in the early 1800s.

During the 1787 Constitutional Convention, a compromise was made about how to count enslaved people for representation in Congress. Northern states wanted to count only free black people. Southern states wanted to count all enslaved people. The "Three-fifths Compromise" counted enslaved people as three-fifths of a person. Free black people were counted as one full citizen. This compromise gave Southern states more political power than their white voting population alone would have.

Southern states also passed strict laws about free black people. Some states even banned them from entering or living there. In Mississippi, a free black person could be sold into slavery after ten days in the state. Arkansas passed a law in 1859 that would have enslaved every free black person still there by 1860. This law was not fully enforced, but it made most free black people leave Arkansas. Some Northern states also limited where free black people could move.

The movement to end slavery gained support from both black and white people in the North. During the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln's government passed laws to help black people gain freedom. The Confiscation Act of 1861 allowed enslaved people who escaped to Union lines to stay free. The Confiscation Act of 1862 guaranteed freedom for escaped slaves and their families. The Militia Act allowed black men to join the military.

In January 1863, Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation freed enslaved people only in areas controlled by the Confederacy. Black men were officially allowed to serve in the Union Army. Their fighting was very important for the Union victory.

In 1865, the Union won the Civil War. The Thirteenth Amendment was added to the U.S. Constitution, banning slavery everywhere. Southern states then passed "Black Codes" to control black labor. These codes put limits on the freedom of all black people, whether they were newly freed or had been free before the war. Black people born in the U.S. gained legal citizenship with the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and later the Fourteenth Amendment.

Life in Different Regions

Moving to Cities

The lives of free black people were different depending on where they lived in the United States. Many free black people moved to cities over time, both in the North and the South. Cities offered more job and social opportunities. Most southern cities had black-run churches and secret schools. Northern cities also offered better chances. For example, free black people in Boston generally had more access to formal education.

In the South

Before the American Revolution, there were very few free black people in the Southern colonies. The number of free black people in cities grew faster than the total free black population. This was because many free black people from rural areas moved to cities like Richmond, Petersburg, Charleston, and Savannah.

The South had two main groups of free black people. Those in the Upper South were more numerous. In 1860, Maryland had 83,942 free black people, and Virginia had 58,042. In contrast, Arkansas had only 144, and Mississippi had 773. Free black people in the Lower South were more likely to live in cities, be educated, and be wealthier. They were also more often of mixed race with white fathers. Despite these differences, Southern states passed similar laws to control black life.

Free Black People Not Welcome

The numbers show that Southern states tried to make free black people leave. Many Southerners believed that free black people were a threat to the system of slavery. They thought free black people showed that being free had no advantages. So, free black people became targets of slaveholders' fears. Laws became stricter. Free black people had to accept their new role or leave the state.

In Florida, for example, laws in 1827 and 1828 stopped them from joining public gatherings or giving "seditious speeches." Laws in 1825, 1828, and 1833 ended their right to carry guns. They could not serve on juries or testify against white people. To free a slave, an owner had to pay a tax and promise that the freed person would leave the state within 30 days. Later, some people in Leon County, Florida, asked the government to remove all free black people from the state.

In 1847, Florida passed a law requiring all free black people to have a white person as a legal guardian. In 1855, a law was passed to stop free black people from entering the state. In 1861, a law required all free black people in Florida to register with a judge. They had to give their name, age, color, sex, and job, and pay one dollar. All black people over twelve years old had to have a guardian approved by the judge. If a free black person did not register, they were considered a slave and became the property of any white person who claimed them.

Free black people were ordered to leave Arkansas by January 1, 1860, or they would be enslaved. Most of them left.

Moving from South to North

Even with many free black people in the South, they often moved to Northern states. While this caused some problems, free black people generally found more opportunities in the North. During the 1800s, the number of free black people in the South decreased as many moved North. Some important and talented free black leaders moved North for better chances. Some returned after the Civil War to help with the Reconstruction Era. They started businesses and were elected to political office. This difference in where free black people lived lasted until the Civil War. At that time, about 250,000 free black people lived in the South.

Chances for Improvement

Free black people could not enter many professional jobs, like medicine and law. This was because they were not allowed to get the necessary education. This was also true for jobs that needed guns, elected office, or a liquor license. Many of these jobs also needed a lot of money to start, which most free black people did not have. However, there were some exceptions, like doctors Sarah Parker Remond and Martin Delany.

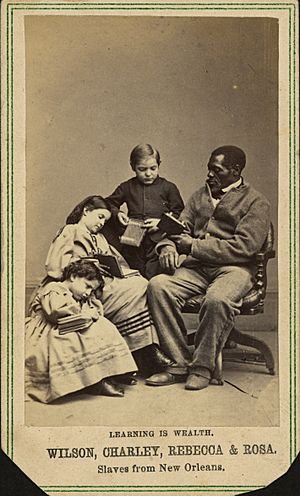

In the 1830s, white communities tried to stop black education. This happened as public schooling grew in northern American society. Public schooling and citizenship were linked. Because black people's citizenship status was unclear, they were often kept out of public education. However, the free black community in Baltimore made more progress in black education than Boston or New Haven. Most Southern states did not have public education until after the Civil War. Educated free black people created literary societies in the North. These societies made libraries available to black people when books were expensive.

Free black men had more job opportunities than free black women. Women were mostly limited to domestic jobs. Free black boys could become apprentices to carpenters, barbers, and blacksmiths. Girls' options were much more limited, like cooks, cleaning women, seamstresses, and child caregivers. Despite this, in some areas, free black women became important members of their communities. They ran households and made up a large part of the paid workforce. Teaching was one of the most skilled jobs for women.

Many free African-American families in colonial North Carolina and Virginia owned land. Some also owned slaves. In some cases, they bought their own family members to protect them until they could set them free. In other cases, they took part in the slave economy. For example, a freedman named Cyprian Ricard bought a property in Louisiana that included 100 enslaved people.

Free black people signed petitions and joined the army during the American Revolution. They hoped to gain freedom. This hope grew when British official Lord Dunmore promised freedom to any enslaved person who fought for the British. Black people also fought for the Americans, hoping for citizenship later. During the Civil War, free black people fought for both the Confederate and Union sides. Southern free black people who fought for the Confederacy hoped to gain more acceptance from their white neighbors. The hope of equality through military service was slowly realized. For example, black and white soldiers received equal pay a month before the Civil War ended.

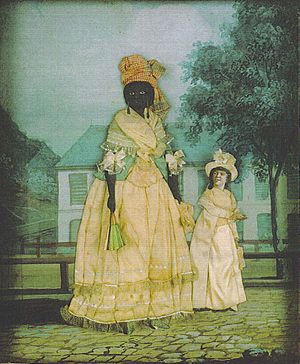

Women's Lives

Within free black marriages, many women could be more equal partners than wealthy white women. This potential for equality can be seen in the "colored aristocracy" of St. Louis. Here, women often contributed to the family's income. These small groups of black people were usually descendants of French and Spanish mixed marriages. Under French law, women in these marriages had the same rights as white women and could own property. These black women wanted to stay financially independent to protect themselves and their children from Missouri's strict laws. This level of independence also made female-led households appealing to widows. Women's importance in bringing income meant that the traditional idea of a husband controlling his wife was not always central in these elite marriages. However, women had to be careful. If a free black woman married a black man who was still enslaved, she became legally responsible for his actions.

There are many examples of free black women taking action in society, including using legal power. Slavery and freedom existed together, creating a dangerous situation for free black people. The story of Margaret Morgan and her family from 1832 to 1837 shows how dangerous the unclear legal definitions of their status were. Their legal case led to Prigg v. Pennsylvania. In this case, the court decided that their captors could ignore Pennsylvania's personal liberty law and claim ownership of the Morgans. This case showed how unclear black rights were in the Constitution. It also showed how some white people actively tried to limit those rights.

In New England, enslaved women went to court to gain their freedom. Free black women went to court to keep theirs. The New England legal system was unique because free black people could access it and get lawyers. Women's freedom lawsuits were often based on small legal details. For example, they might argue there were no proper slave documents, or that their mixed-race background meant they should not be enslaved. In 1716, Joan Jackson became the first enslaved woman to win her freedom in a New England court.

Elizabeth Freeman was the first to legally challenge slavery in Massachusetts after the American Revolution. She argued that the state's new constitution, which said all men were equal, meant slavery could not exist. As a landowner and taxpayer, she is one of the most famous black women of the revolutionary era.

Notable Free Black People

Born before 1800

- Richard Allen: Started the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent black church in the U.S.

- Benjamin Banneker: Wrote almanacs, studied stars, surveyed land, and was a farmer.

- James Derham: The first African American to formally practice medicine in the United States.

- Elizabeth Freeman: A healer, midwife, and nurse who sued for her freedom in 1781.

- Prince Hall: A famous leader in the free black community in Boston and founder of Prince Hall Freemasonry.

- Thomaston L. Jennings: The first black man to get a U.S. patent (a special right for an invention).

- Anthony Johnson (colonist): A former slave who later became a slave owner.

- Absalom Jones: The first ordained black Episcopal priest.

- John Berry Meachum: A Baptist minister, businessman, and educator.

- Jane Minor: A healer who helped free enslaved people.

- Jean Baptiste Point du Sable: The founder of Chicago and a trader.

- Lucy Terry: An author.

- Sojourner Truth: An activist who fought to end slavery and for women's rights.

- David Walker: An activist who fought to end slavery.

- Phillis Wheatley: The first African-American woman to publish poetry.

- Theodore S. Wright: A minister and co-founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society.

Born 1800–1865

- William Wells Brown: An escaped slave, author, playwright, and activist.

- Charlotte L. Brown: A civil rights activist in San Francisco in the 1860s.

- Thomas Day: A very skilled cabinetmaker and activist against slavery from North Carolina.

- Martin Delany: An activist against slavery, writer, doctor, and supporter of black nationalism.

- Moses Dickson: An activist against slavery, soldier, minister, and organizer.

- Frederick Douglass: An escaped slave, reformer, writer, and statesman.

- William Ellison: A property owner and businessman.

- Henry Highland Garnet: An activist against slavery and educator.

- Cynthia Hesdra: A former slave and businesswoman in New York.

- Harriet Jacobs: A writer and activist against slavery.

- Biddy Mason: A nurse, midwife, business owner, and giver to charity.

- Mary Meachum: A conductor on the Underground Railroad and president of the Colored Ladies Soldiers Aid Society.

- William Cooper Nell: A journalist.

- William Nesbit: A civil rights activist in Pennsylvania.

- Solomon Northup: The writer of the slave story Twelve Years a Slave.

- Sarah Parker Remond: A lecturer, activist against slavery, and doctor.

- Charles Lenox Remond

- Daniel Payne: An educator, college leader, and author.

- Robert Purvis: An activist against slavery.

- David Ruggles: An activist against slavery.

- Heyward Shepherd: Killed during John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry.

- Michael Shiner: A diarist (someone who keeps a diary).

- Maria Stewart: A journalist, activist against slavery, and activist.

- William Still: An activist against slavery, writer, and activist.

- Pierre and Juliette Toussaint: People who gave to charity.

- Harriet Tubman: An escaped slave, activist against slavery, and organizer ("conductor") on the Underground Railroad.

- Harriet Wilson: A novelist.

See also

In Spanish: Negro libre para niños

In Spanish: Negro libre para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |