Charlotte L. Brown facts for kids

Charlotte L. Brown (born 1839) was an American teacher and a champion for equal rights. She was one of the first people to legally fight against unfair rules that separated people by race in the United States. In the 1860s, she sued a streetcar company in San Francisco after they made her leave a streetcar because of her race.

Contents

Charlotte Brown's Early Life

Charlotte Brown was born in Maryland in 1839. Her father, James E. Brown, was born into slavery. Her mother, also named Charlotte Brown, was a free seamstress. Charlotte's mother bought her husband's freedom.

By 1850, the family lived in Baltimore, Maryland, as free people of color. Between 1850 and 1860, they moved to San Francisco. The city was growing fast because of the California Gold Rush. The Brown family became part of the city's growing Black middle class. About 1,176 Black people lived in San Francisco then, which was about 2 percent of the city's population.

In San Francisco, Charlotte's father, James E. Brown, ran a stable for horses. He also helped run a Black newspaper called Mirror of the Times. He worked to end slavery and was part of a discussion group for important African American men. In 1855, when Charlotte was a teenager, she was a bridesmaid at her sister Margaret's wedding. Margaret married a wealthy Black businessman named George Washington Dennis.

The Streetcar Incident

On April 17, 1863, at 8 PM, Charlotte Brown got on a horse-drawn streetcar. She was going to see her doctor. The streetcar was owned by the Omnibus Railroad Company. When the conductor asked her to leave, Charlotte said she "had a right to ride." She did not plan to get off the car.

In court, she explained what happened: "The conductor collected tickets. When he came to me, I gave him my ticket. He refused to take it. It was an Omnibus railroad ticket I had bought before. He said that Black people were not allowed to ride. I told him I had been riding ever since the cars started running. I said I had a long way to go and was already late."

The conductor, Thomas Dennison, asked her to leave many times. Each time, she refused. Finally, a white woman on the streetcar complained about Charlotte being there. The conductor then grabbed Charlotte's arm and made her get off the car.

Charlotte Brown Sues the Railroad

Charlotte's father, James E. Brown, hired a lawyer. Charlotte then sued the Omnibus Railroad Company for $200. This happened in the same year that African Americans gained the right to speak in court against white people.

The Omnibus Railroad Company argued that the conductor was right to remove her. They said that separating people by race protected white women and children. They claimed these passengers might be scared or "repulsed" by riding with African Americans.

Charlotte won her case, which was overseen by Judge Cowles. However, the jury only gave her twenty-five dollars. The conductor, Dennison, was also found guilty in a separate court case for treating Charlotte badly.

Charlotte's case was appealed for the next two years. In one new trial, the jury first gave her $25 plus court costs. But this amount was later lowered to only five cents, which was the price of the streetcar ticket.

Just three days after the first trial, Charlotte was forced off another streetcar. She then filed a second lawsuit against Omnibus, this time for $3,000. Finally, in October 1864, her case was heard in a higher court. On October 5, 1864, Judge Orville C. Pratt of the 12th District Court supported the earlier decision in Charlotte's favor. He ruled that it was illegal to stop passengers from riding streetcars because of their race. He said he did not want to "perpetuate a relic of barbarism."

Judge Pratt stated in his ruling: "It has been tolerated for too long by the main race to see Black or mixed-race people treated like animals. They are insulted, wronged, enslaved, made to wear a yoke, to tremble before white men, to serve him as a tool, to have property and life at his will, to give up their minds and beliefs, and to keep quiet and hide their thoughts because they fear the white man's power."

In January 1865, a jury awarded Charlotte $500. The Omnibus Railroad Company tried to appeal this decision, but they were not allowed another trial.

Public Reaction to the Case

After the first trial, a Black-owned newspaper called the Pacific Appeal wrote about the case. They noted that the decision in Charlotte's favor "establishes the right, by law, of colored persons to ride in such conveyances."

The newspaper's article continued: "The law gives us the right to ride in these cars. But some employees of this Company, if a Black person tries to cross the street near their car, get a sudden fear of Black people. They usually ring their alarm bell loudly, as if there's danger. They are so afraid that other respectable Black women might try to use the right Miss Brown just won. As long as we have law, justice, and right on our side, we don't need pity."

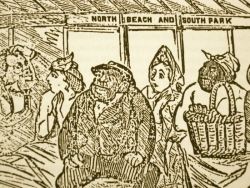

Judge Pratt's 1864 ruling was made fun of in a cartoon by a local white-owned newspaper. The cartoon showed Black and white people riding together. It used a rude name for Black people and accused Judge Pratt of favoring them. It also questioned if Charlotte Brown, who had light skin, was truly Black or just suing for money.

However, a white editor of The Sacramento Daily Union supported Judge Pratt's decision. He said, "his argument is clear, and his decision, we believe, agrees with what the people think."

Charlotte Brown's case helped other African Americans in San Francisco, like William Bowen and Mary Ellen Pleasant, to challenge "whites-only" rules on private streetcars. In 1893, the California government officially made streetcar segregation illegal across the state.

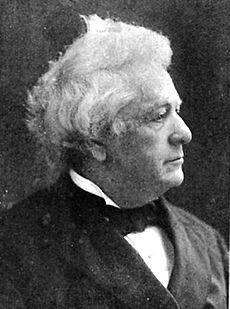

After Charlotte Brown won her case, Senator Charles Sumner mentioned it in Congress. He said it was an important example for equal rights. He used her case to argue for ending segregation on streetcars in the nation's capital.

Charlotte Brown's Later Life

In 1867, Charlotte Brown opened a school for young children. It was located at 10 Scotland Street in San Francisco. She taught "all the basics of early education," along with music and embroidery.

In 1874, she married James Henry Riker. He was another important African American activist in San Francisco. He had worked as a personal helper for William Chapman Ralston. During their marriage, he was a steward at the Palace Hotel. James Riker, along with Charlotte's father, helped organize a meeting for Black citizens in California in 1865.

In 1877, a Black newspaper called The Elevator announced a surprise party. Charlotte and James H. Riker hosted it at their home for a fellow steward from the Palace Hotel. Not much is known about Charlotte Brown Riker's life after that time.

Historical Importance

Charlotte Brown's lawsuit was one of the first of many actions taken by Black activists. These actions protested unfair exclusion and segregation on public transportation. This happened in both Southern and Northern cities across the United States in the 1800s and 1900s.

In 1854, Elizabeth Jennings Graham successfully sued the Third Avenue Railway Company in New York City. She had been forced off a streetcar because of her skin color. In Philadelphia in 1865, a "Mrs. Derry" won a lawsuit and $50. A streetcar conductor had thrown her off the bus and kicked her. This happened when she and other women were returning from helping Civil War soldiers.

Other important figures like Sojourner Truth, Ida B. Wells, and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper also worked hard for streetcar integration. They had been refused rides on streetcars in Washington, D.C., Memphis, and Pennsylvania.

By the end of the 1800s, streetcars in the North were mostly desegregated. However, segregation on public transportation became official policy in many Southern cities. In the 1900s, women like Irene Morgan, Claudette Colvin, and Mary Louise Smith continued to fight segregation on public transportation. In 1954, Rosa Parks challenged this practice in Montgomery, Alabama. Her actions led to a citywide bus boycott and helped start the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Scholars Quintard Taylor and Shirley Ann Wilson Moore studied Charlotte Brown's case. They also looked at other 1800s streetcar lawsuits brought by Black women. They noted that women often filed these lawsuits. This was because of common ideas about public spaces and white views of Black women's roles.

They wrote: "Active Black men knew that Black women could go where they, as men, could not. By using the idea of gender, Black women's lawsuits against streetcar companies eventually made sure that all Black people had the right to travel... the law's declaration applied not just to Charlotte Brown or to Mary Pleasant, but to all Black people as well."

See also

- List of 19th-century African-American civil rights activists

- Jim Crow laws

- African Americans in San Francisco

- Elizabeth Jennings Graham, in 1854, she sued and won a case that led to desegregation of streetcars in New York City

- John Mitchell Jr., in 1904, he organized a Black boycott of Richmond, Virginia's segregated trolley system

- Irene Morgan, in 1944, she sued and won a Supreme Court ruling that segregation of interstate buses was unconstitutional

- Rosa Parks, she inspired a boycott against segregated buses in the 1950s in Montgomery, Alabama