Mary Ellen Pleasant facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mary Ellen Pleasant

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | August 19, 1815 |

| Died | January 11, 1904 |

| Known for | Entrepreneur and abolitionist |

Mary Ellen Pleasant (born August 19, 1815 – died January 11, 1904) was a powerful woman in the 1800s. She was a successful businesswoman, investor, and a strong supporter of ending slavery. Many believe she was the first self-made African-American millionaire. She became rich decades before Madam C. J. Walker.

Mary Ellen called herself "a capitalist by profession." This meant she aimed to earn a lot of money. Her goal was to use her wealth to help as many people as possible. She provided transportation, housing, and food for those in need. She also taught people how to stay safe and succeed. She was like a "one-woman social agency." She helped African Americans before and during the Civil War. After slavery ended, she continued to help people in new ways.

She played a big part in the Underground Railroad. This secret network helped enslaved people escape to freedom. She even expanded its reach westward during the California Gold Rush. Mary Ellen was a friend and supporter of John Brown, a famous abolitionist. She was well-known among those fighting against slavery. In California, she helped women stay safe and become independent. After the Civil War, she won important civil rights cases. Because of her efforts, she was called "The Mother of Human Rights in California."

Mary Ellen was a Black woman who gained a lot of power and wealth. She found ways to fit into society at the time. For many years, even after she was rich, she pretended to be a housekeeper or cook. She used these roles to meet wealthy people. This helped her gather information for her smart investments. In the 1870s, she met Thomas Bell, a rich banker. This partnership helped her earn more money. It also helped her keep her true wealth a secret. She used her money to build a large mansion. It looked like the Bells' home, but Mary Ellen actually ran everything. She managed the servants and even the family's relationships.

Author Edward White described her well. He said Mary Ellen was an "entrepreneur, civil-rights activist, and benefactor." She made a name and a fortune in San Francisco. She also broke down racial barriers.

Contents

Mary Ellen's Early Life

Mary Ellen Pleasant was likely born on August 19, 1814. There are different stories about where she was born. Some say she was born free in Philadelphia. Others say she was born into slavery in Georgia or Virginia. She told different stories about her past. She did this to "please her audience or justify her behavior."

When she was a child, her mother disappeared. She then lived with Mr. and Mrs. Williams. She was known as Mary Ellen Williams. When she was about six or eleven, she was taken from Philadelphia or Cincinnati. Mr. Williams brought her to Nantucket, Massachusetts. There, she became a servant for the Hussey-Gardner family. They were Quakers and against slavery. Mr. Williams left money for her education. But Mary Ellen did not get a formal education. She later said, "I often wonder what I would have been with an education."

Around 1820, Nantucket was a busy whaling town. Mary Ellen grew up working in the Hussey family's store. This store was run by Mary Hussey, whom Mary Ellen called "Grandma Hussey." Working there helped her learn about business. She also learned how to be friendly with people. She said, "I was a girl full of smartness [who] let books alone and studied men and women a good deal." By 1839, she was like a family member. Phebe Hussey Gardner and Edward Gardner, who were abolitionists, took her into their home. Their son, Thomas Gardner, taught her to read and write. She left Nantucket around 1840. She kept writing letters to Phebe Gardner and Ariel Hussey until they passed away.

Helping Enslaved People Escape

Mary Ellen became an apprentice for a tailor in Boston. She may have met her first husband, James Smith, there. They married in Boston in the 1840s. James was an abolitionist, like her. Together, they helped enslaved people escape to freedom in Nova Scotia. They used the Underground Railroad to coordinate travel. They had contacts in Nantucket, New Bedford, Massachusetts, Ohio, and possibly New Orleans. James also worked for The Liberator. This was an anti-slavery newspaper. Mary Ellen likely attended anti-slavery meetings.

James died after about four years of marriage. Mary Ellen inherited a lot of money from him. She continued their work on the Underground Railroad for several years. This work was dangerous. She was harassed for helping runaways. She faced prosecution and imprisonment. This was under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and the later act of 1850. These laws made it risky to help enslaved people.

After her husband's death, she returned to Nantucket for a short time. Edward Gardner helped her manage her husband's estate. At some point, Mary Ellen started a relationship with John James Pleasants. He was a former enslaved person. They married around 1848. She had a daughter named Elizabeth "Lizzie" J. Smith in the late 1840s. Lizzie likely stayed on the East Coast. She later traveled west to San Francisco with Mrs. Martha Steele.

Many abolitionists moved to California around 1850. More than 700 people, including many from the Hussey and Gardner families, left Nantucket for the Gold Coast. Mary Ellen sailed to New Orleans. There, she helped enslaved people escape. She also took cooking lessons. It is said she learned from the Voodoo Queen Marie Laveau. Mary Ellen arrived in San Francisco in 1849 or April 1852. She traveled through Panama. She left New Orleans just before she could be caught for her Underground Railroad activities. The trip to California took about four months.

California Gold Rush and Civil Rights

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) offered a special chance for Black people. One African American miner wrote, "This is the best place for black folks on the globe. All a man has to do is to work, and he will make money." Many Black people became rich by finding gold.

Only one out of ten pioneers in California were women. Mary Ellen saw a great chance to make money. She could cook and provide lodging for miners. However, there was a problem. Many Southerners came to California, bringing enslaved people with them. There were also slave catchers looking for runaways. California had a law that allowed any Black person to be sold into slavery if they did not have the right papers.

Making Money in California

When Mary Ellen arrived in San Francisco, people already knew she was coming. A group of men competed to hire her as a cook.

She reportedly had $15,000 in gold coins when she arrived. She managed her money very smartly. She exchanged gold for silver when gold was high in value. She deposited silver in banks and took out gold. She said she "was able to turn my money over rapidly." She put money into several banks. She also lent money to others, like a Black Baptist minister, Thomas Randolph, and businessmen William West and Frank Langford, at a 10% interest rate.

Mary Ellen worked as a live-in domestic servant. She made investments based on conversations she overheard from wealthy men. She listened while serving them meals or during their meetings. She started boarding houses and laundries. She also helped start the Bank of California. She opened several restaurants, including the Case and Heiser. Her husband, John James Pleasant, was a sea-cook. He was often at sea during their 30-year marriage. He worked with her for over two decades as an abolitionist. He also fought against discrimination in the 1860s. He passed away in 1877.

Helping Others and Fighting for Rights

The more money Mary Ellen made, the more she shared. She helped people who needed it. For her own safety, she first used the name Mrs. Ellen Smith. Her neighbors thought she was a white landlady and cook. But to former enslaved people who worked for her, she was Mrs. Pleasant. She owned livery stables, a dairy farm, a tenant farm, and a money-lending business. She was careful to keep her name out of Underground Railroad records. However, other abolitionists knew her as Mrs. Pleasant(s). She helped enslaved people get safe transportation, housing, and jobs. She funded these efforts with the money from her first husband's estate.

When she came to California, enslaved people could be caught and returned to other states. Black people were also not allowed to speak in court. Mary Ellen became a "one-woman social agency." She arranged for Black men and women to travel to California. Once they arrived, she made sure they had their daily needs met. She helped them find jobs or start businesses. She helped William Marcus West open a boarding house. This house also served as a safe place for runaways, as did her own home. She helped enslaved people escape while traveling with their owners in California.

She found legal help for Black people. This was important when others tried to send them back to slavery. For example, she paid for legal fees and housing for Archy Lee in 1857. In that case, a judge ruled against California's constitution. Since Black people could not testify in court, she worked to change that law. She also campaigned to end slavery in the state. Because of her efforts, she became known as the "Mother of Civil Rights in California."

She also helped women of all backgrounds. In early San Francisco, women were at high risk on their own. Mary Ellen helped them with housing and clothing. She also advised them on how to present themselves. She even helped women find homes for their children if they could not support them.

Supporting John Brown

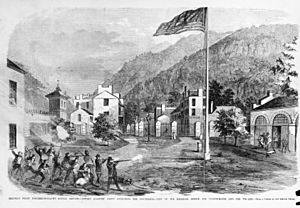

Mary Ellen left San Francisco from 1857 to 1859. She went to help John Brown. She actively supported his cause with money and work. A note from her was found in his pocket when he was arrested. This was after the Harpers Ferry Armory incident. The note was only signed with the initials "MEP." These were misread as "WEP," so she was not caught. She returned to San Francisco to continue her work. There, she was known as the "Black City Hall."

When John Brown was executed on December 2, 1859, a note was found in his pocket. It read, "The ax is laid at the foot of the tree. When the first blow is struck, there will be more money to help." Officials thought a rich Northerner had written it. They believed this person funded Brown's plan to start a slave uprising. No one suspected Mary Ellen Pleasant wrote the note.

Mary Ellen later said she wanted to reveal who gave John Brown most of his money. She said she signed the letter found on him. She donated $30,000 to his cause. She called this the "most important and significant act of her life."

Life After the War

Mary Ellen used her fortune and the high wages she earned as a cook. She invested in many businesses in California. These businesses served miners. They included laundries, lodging, and even Wells Fargo. She formed a long-lasting partnership with Thomas Bell, a white banker. By 1875, her investments and businesses made her and Thomas Bell $30 million. After the Civil War ended, she invested in similar businesses. But now, they were more luxurious. These attracted wealthy people.

After the war, she began to openly identify as a woman of color. She stopped working as a housekeeper. This gave her more time for civil rights work. She helped provide housing for Black people. She also helped establish Black schools. She fought against Jim Crow laws, which enforced segregation. In 1890 and 1891, she established a 1,000-acre ranch in Sonoma County. It was called Beltane Ranch. Today, it is part of the Calabazas Creek Open Space Preserve.

In the spring of 1865, her daughter Lizzie married R. Berry Phillips. The wedding was at the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Zion Church in San Francisco. A reception followed. Mary Ellen herself was Catholic.

Fighting for Justice

Streetcar Lawsuits

Mary Ellen successfully fought against racial discrimination on San Francisco streetcars. In 1866, she and two other Black women were forced off a city streetcar. She filed two lawsuits. The first one was against the Omnibus Railroad Company. She withdrew it after the company promised to let African Americans ride their streetcars. The second case, Pleasant v. North Beach & Mission Railroad Company, went to the California Supreme Court. It took two years to finish. This case made segregation illegal on the city's public transportation. She won partly because a white woman testified for her. This woman had hired Mary Ellen for domestic work years ago. The woman called Mary Ellen "Mamma." This term was twisted by newspapers. At the State Supreme Court, the damages she was awarded were reversed. They were found to be too high.

The publicity from this case showed how different Mary Ellen was. She was a woman of mixed heritage. She lived boldly for her time. She also had a big change in her social class. Local white people often called her the disrespectful name "Mammy Pleasant." The press also used this name. But she did not like it. She said, "I don't like to be called mammy by everybody. Put. that. down. I am not mammy to everybody in California. I received a letter from a pastor in Sacramento. It was addressed to Mammy Pleasant. I wrote back to him on his own paper that my name was Mrs. Mary E. Pleasant. I wouldn't waste any of my paper on him."

Legal Challenges with the Bell Family

Mary Ellen lived her last 20 years in a large, 30-room mansion. It covered two city blocks in San Francisco. In 1880, fifteen people lived in her house. This included five members of Thomas Bell's family. There was his wife Terressa (or Teresa) Bell, and their children. The rest were servants and a five-year-old boy.

While the Bells and Mary Ellen lived together, Mary Ellen controlled their combined money. If Teresa wanted money, she asked Mary Ellen. Mary Ellen would consider the request. If it seemed reasonable, she would check with Thomas Bell. After Thomas Bell died in 1892, Mary Ellen lost most of her wealth. She still had investments, but she was short on cash. The courts declared that Mary Ellen was unable to pay her debts. That same year, she donated about $10,000 (in today's money) to help found Saint Mary's College.

Teresa Bell claimed that Mary Ellen had stolen tens of thousands of dollars. She also claimed that her husband had been manipulated. When the case went to trial, it was hard to tell what belonged to Bell and what belonged to Mary Ellen. Their financial dealings were very mixed up. Mary Ellen could show she paid for her mansion's construction. But she left it in 1899. This was either because a court ruled the ownership should go to Teresa, or Mary Ellen agreed to Teresa's request to leave. As soon as she made arrangements, she moved into a six-room apartment. She then started her own legal fight to get her property back. This included a diamond collection. The case was not settled by the time Mary Ellen passed away.

Mary Ellen's Final Days

Mary Ellen lived on Webster Street in San Francisco with a maid. The Bell children visited her there. They called her "Auntie," and she called them "Dear." A reporter offered to pay her a lot for her stories about people from the past. But she refused. She said she would never betray her friends. She became very weak and near death. A friend, Olive Sherwood, took her to her house. Mary Ellen died there on January 11, 1904. She was buried at Tulocay Cemetery in Napa, California. Her grave has a metal sculpture. It was dedicated on June 11, 2011. Her gravestone has the words "She was a friend of John Brown." This is what she had asked for before she died. Her former mansion was torn down. The Mary Ellen Pleasant Memorial Park is now in its place.

Remembering Mary Ellen Pleasant

Mary Ellen Pleasant has been featured in many books. Michelle Cliff's 1993 book Free Enterprise is about her abolitionist work. Mary Ellen Pleasant's ghost is a character in Tim Powers' 1997 novel Earthquake Weather. Karen Joy Fowler's 2001 historical novel Sister Noon features Mary Ellen as a main character. She was also an important character in Andre Norton's Velvet Shadows.

Mary Ellen's life has also been shown in films and on TV. This includes the 2008 documentary Meet Mary Pleasant. She was also in a 2013 episode of the Comedy Central series ... History. In that show, Lisa Bonet played Mary Ellen.

In 1974, San Francisco recognized the eucalyptus trees Mary Ellen planted. These trees were outside her mansion at Octavia and Bush streets. They were named a "Structure of Merit." The trees and a plaque are now known as Mary Ellen Pleasant Memorial Park. It is the smallest park in San Francisco. Her burial site is a "Network to Freedom" site. This was given by the National Park Service. Pleasant Street on Nob Hill is named after her.

Images for kids

-

Frank Schneider, Portrait of Marie Laveau (1794–1881), 1920, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans. Mary Ellen Pleasant was said to have learned about Louisiana Voodoo from Marie Laveau.

-

Battleground of the Harper's Ferry insurrection, with Captain E. G. Alburtis' party attacking the insurgents, wood engraving, November 5, 1859, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |