Slave catcher facts for kids

In the United States, a slave catcher was a person whose job was to find and bring back enslaved people who had run away from their owners. These individuals were first active in the Americas in the 1500s, in European colonies in the West Indies. Later, in places like colonial Virginia and Carolina, slave catchers became part of a system called the slave patrol. They were hired by large farm owners, known as planters, starting in the 1700s. This idea quickly spread across the Thirteen Colonies.

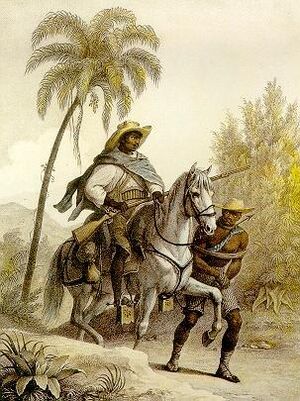

After the United States was formed, slave catchers continued their work. They were also active in other countries where slavery still existed, such as Brazil. Their actions became a big issue leading up to the American Civil War. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 even made people in the Northern United States help slave catchers. Slave catchers stopped working in the United States when the Thirteenth Amendment was passed, which ended slavery.

Contents

History of Slave Catchers

The first slave catchers in the Americas started their work in the 1500s. They were active in European colonies in the West Indies. In colonial Virginia and Carolina, slave catchers were part of the slave patrol system. Large farm owners, called planters, hired them in the 1700s to find enslaved people who had escaped. This practice quickly spread to all the Thirteen Colonies.

These early slave catchers were white colonists. Planters paid them to control the growing number of enslaved people. This growth was due to the Atlantic slave trade, which brought many people from Africa. At first, there were not many slave catchers. They had to cover very large areas. Because of this, many enslaved people were able to escape. They found places where they could live as free people of color.

Law Enforcement in Colonial America

During the colonial period in the United States, a system for enforcing laws began to form. It was similar to systems in Europe. In the Northern Colonies, there were "watchmen." Private citizens hired them to patrol streets and keep order. In the Southern Colonies, law enforcement mostly focused on controlling the large number of enslaved African Americans. These enslaved people worked on big farms called plantations.

Groups of slave catchers included both planters and colonists who did not own slaves. Planters paid them to search for escaped slaves. However, the Southern Colonies had fewer people spread out over larger areas. This made it hard for slave catchers. Even though slavery existed in the North, most enslaved people lived in the South. This meant more slave catchers were active there.

Historians have noted that women planters also sometimes helped to recapture escaped slaves. Almost anyone could try to be a slave hunter. But only a few were very successful.

These Southern law enforcement groups continued after the American Revolution. They were created to keep order among enslaved people and their owners. Many Southern planters worried if their enslaved property escaped. They feared that more escapes would break down the system. It was believed that all planters needed to keep strict control. This was to prevent enslaved people from starting a slave rebellion.

Many states allowed local law enforcement to get help from federal marshals and other local citizens. This became even more common with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This law required all citizens and local police to help catch runaway slaves. This meant that Northerners, many of whom were abolitionists (people who wanted to end slavery), had to work with slave catchers. However, they often found ways to avoid this rule.

Before this law, many states tried to stop slave catchers. For example, Massachusetts passed a law in 1842. It stopped slave catchers from getting help from state officials. But the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 canceled these efforts. Abolitionists then had to find smaller ways to resist. In some areas, it was even dangerous to be a slave catcher because local people were against them.

Under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, slave hunters could easily get an "Order of Removal." This order allowed them to return a runaway slave. But Northern abolitionists often resisted these orders. They would try to block slave catchers from entering rooms where a runaway was held. Local governments tried to stop this resistance. They offered police officers more money for returning a slave to the South. This was more than abolitionists would pay police to ignore the law.

During the American Civil War, these law enforcement groups faced great difficulties. Most white men were away fighting in the war. Women had to manage households and keep enslaved people in line. With fewer punishments and more chances to escape, more enslaved people ran away. Slave patrols were spread very thin. Many enslaved people were able to escape, often with help from Union soldiers. Many of these escaped people joined the Union army, becoming part of the United States Colored Troops. They fought against their former owners.

Mercenaries

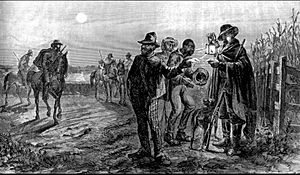

When an enslaved person ran away, citizens or local police would often question them. They would ask to see papers proving they were free. Slave owners hired people who made a living by catching runaway slaves. These slave catchers charged money based on the day and how far they traveled. Many would go long distances to hunt for runaways.

Slave catchers often used tracking dogs to find their targets. These dogs were sometimes called "negro dogs." They could be different breeds, but bloodhounds were common.

If an enslaved person reached the Northern "free" states, a slave catcher's job became much harder. Even if they found the runaway, they might face resistance from people who were against slavery. If a slave managed to escape that far, owners usually sent someone closely connected to them. Or they would put out advertisements about the escaped slave.

Fugitive Slave Laws

White abolitionists and anyone else who helped free or hide enslaved people were punished. One story tells of about 200 U.S. Marines escorting one runaway slave back to his owner. Laws in the North punished both those who helped slaves escape and the escaped slaves themselves. Because of this, many enslaved people fled to Canada, where slavery had been ended in 1834.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made slave catchers' jobs easier. It required government officials to find and prosecute runaway slaves. This gave slave catchers more freedom to act under the law. With this law, slave catchers could get warrants to arrest people identified as runaway slaves.

Northern Responses

People in the North became more and more against slave catchers. Several Northern states passed new personal liberty laws. These laws went against the South's efforts to have slaves captured and returned. Slave-catching was still allowed in the North, and the new laws did not make it impossible. However, it became so difficult, expensive, and time-consuming that slave catchers and owners often stopped trying.

The Fugitive Slave Act made abolitionists even more determined to fight slave catchers. Groups like the Free Soil Party suggested using guns to stop slave catchers and kidnappers. They compared this fight to the American Revolution. The 1850s saw a big increase in violent clashes between abolitionists and law enforcement. Large groups formed to stop actions that threatened runaway slaves.

The number of slave catchers greatly decreased during the American Civil War. Many of them joined or were forced into the Confederate army. The system of slave patrolling disappeared after the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution ended slavery in the United States.

See also

- Slave catcher (Brazil)

- Slave patrol

- Slave pen