Frances Ellen Watkins Harper facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Frances Harper

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Frances Ellen Watkins September 24, 1825 Baltimore, Maryland |

| Died | February 22, 1911 (aged 85) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Genre | Poetry, short story, essays |

| Notable works | Iola Leroy (1892) Sketches of Southern Life (1872) |

| Spouse | Fenton Harper (m. 1860) |

| Children | Mary Frances Harper (1862–1908) |

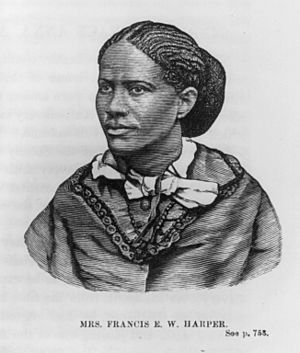

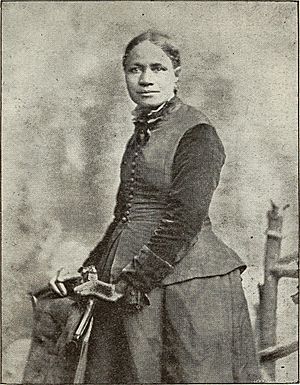

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (born September 24, 1825 – died February 22, 1911) was an amazing American writer, speaker, and activist. She fought for many important causes. These included ending slavery, gaining voting rights for women (called suffrage), and promoting the temperance movement (which encouraged people to avoid alcohol). She was also a teacher and a poet.

Frances Harper was one of the first African-American women to have her writings published in the United States, starting in 1845. She was born free in Baltimore, Maryland. She had a long and successful career. Her first book of poetry was published when she was just 20 years old. Later, at 67, she published her famous novel Iola Leroy (1892). This made her one of the first Black women to publish a novel.

In 1850, she taught home economics at Union Seminary in Columbus, Ohio. This school was connected to the AME Church. In 1851, she lived with William Still, who helped enslaved people escape on the Underground Railroad. During this time, Harper began writing against slavery. In 1853, she joined the American Anti-Slavery Society. This was the start of her career as a public speaker and activist.

Harper also had a very successful writing career. Her book Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects (1854) was very popular. It made her the most famous African-American poet before Paul Laurence Dunbar. Her short story "Two Offers" was published in the Anglo-African in 1859. This made history as the first short story published by a Black woman.

Harper helped start and lead several important groups. In 1886, she became a leader in the Colored Section of the Philadelphia and Pennsylvania Women's Christian Temperance Union. In 1896, she helped create the National Association of Colored Women and served as its vice president.

Frances Harper passed away at age 85 on February 22, 1911. This was nine years before women in the U.S. gained the right to vote.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Frances Ellen Watkins was born free on September 24, 1825, in Baltimore, Maryland. At that time, Maryland was a state where slavery was allowed. Her parents passed away in 1828, when she was only three years old. She was then raised by her aunt and uncle, Henrietta and Rev. William J. Watkins, Sr.. They gave her their last name.

Frances's uncle was a minister at the Sharp Street African Methodist Episcopal Church. She went to the Watkins Academy for Negro Youth, a school her uncle started in 1820. Her uncle was a civil rights activist and abolitionist. He had a big impact on Frances's life and work.

When she was 13, Frances started working as a seamstress and nursemaid for a white family who owned a bookshop. She stopped going to school but used her free time to read books from the shop. She also worked on her own writing.

In 1850, at age 26, Frances moved from Baltimore. She began teaching home economics at Union Seminary. This was a school for Black students near Columbus, Ohio, connected to the AME Church. She was the school's first female teacher. The next year, she took a job at a school in York, Pennsylvania.

Writing Career and Famous Works

Harper's writing career began in 1839. She published her first pieces in journals that were against slavery. Her writing and her political beliefs were closely linked. She started writing many years before she got married, so some of her early works were published under her maiden name, Watkins.

Her first book of poems, Forest Leaves, or Autumn Leaves, came out in 1845 when she was 20. This book showed her as an important voice against slavery. Her second book, Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects (1854), became very popular and was reprinted many times.

In 1858, Harper bravely refused to give up her seat or ride in the "colored" section of a segregated trolley car in Philadelphia. This was 97 years before Rosa Parks did something similar. In the same year, her poem "Bury Me in a Free Land" was published. It became one of her most famous works.

In 1859, Harper's story "The Two Offers" was published in The Anglo-African Newspaper. This made her the first Black woman to publish a short story. In the same year, Anglo-African Magazine published her essay "Our Greatest Want." In this essay, Harper compared the struggles of African Americans to the ancient Hebrew people enslaved in Egypt. These magazines were important places for abolitionists to share ideas.

Harper wrote 80 poems. In her poem "The Slave Mother," she showed the sad reality of an enslaved mother and her child. She wrote about how a mother's child could be taken away. This poem explored themes of family, motherhood, humanity, and slavery. Another poem, "To the Cleveland Union Savers," supported Sara Lucy Bagby. Bagby was the last person in the U.S. to be returned to slavery under the Fugitive Slave Law.

In 1872, Harper published Sketches of Southern Life. This book of poems described her travels in the South. She met newly freed Black people and wrote about the difficult lives of Black women during slavery and the Reconstruction era. She used a character named Aunt Chloe, an ex-slave, to tell some of these stories.

From 1868 to 1888, three of Harper's novels were published in a Christian magazine. These were Minnie's Sacrifice, Sowing and Reaping, and Trial and Triumph.

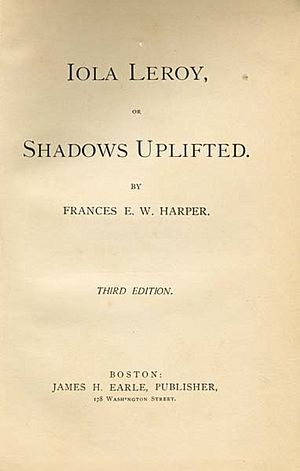

Harper is also well-known for her novel, Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted. It was published as a book in 1892 when she was 67. This was one of the first books published by a Black woman in the U.S. In this novel, Harper discussed important social issues. These included education for women, people of mixed-race who could pass as white, and the fight against slavery. She also wrote about the Reconstruction period and the temperance movement.

Harper was a friend and mentor to many other African-American writers and journalists. These included Mary Shadd Cary, Ida B. Wells, and Victoria Earle Matthews.

Fighting for Change

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper strongly supported several important causes. These included ending slavery (abolitionism), stopping the sale of alcohol (prohibition), and giving women the right to vote (woman's suffrage). These causes were often linked before and after the American Civil War. She was also active in the Unitarian Church, which supported ending slavery. Harper wrote to John Brown, a famous abolitionist, after he was arrested. She thanked him for helping her race and hoped his actions would lead to more freedom.

In 1853, Watkins joined the American Anti-Slavery Society. She became a traveling speaker for the group. She gave many speeches and faced a lot of unfair treatment and discrimination. In 1854, she gave her first anti-slavery speech, "The Elevation and Education of Our People." This speech was so successful that she went on a lecture tour in Maine. She loved New England, saying it was a place where kindness surrounded her. However, she found Pennsylvania to be less welcoming to African Americans.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, Harper moved South. She taught newly freed Black people during the Reconstruction Era. She also gave many large public speeches. In 1870, she worked with the Freedmen's Bureau. She encouraged many freedmen in Mobile, Alabama, to "get land" so they could vote and be independent after the Fifteenth Amendment was passed.

Harper was very active in Black organizations. She believed that Black reformers should decide their own goals. From 1883 to 1890, she helped organize events for the National Woman's Christian Temperance Union. She worked with this group because it was important for expanding federal power. As a leader in the Colored Section of the WCTU, Harper helped Black women get involved and organize themselves. She promoted women working together for justice and morality. However, Harper was disappointed when the WCTU leader, Frances Willard, focused more on white women's issues. Willard did not fully support Black women's goals, like fighting for justice for Black people.

Harper continued her public activism in her later years. In 1891, she gave a speech to the National Council of Women of America in Washington D.C. She demanded justice and equal protection under the law for African Americans.

Fighting for Women's Right to Vote

How She Fought for Suffrage

Frances Harper used an approach called intersectionality. This means she combined her fight for African-American civil rights with her fight for women's rights. One of her main concerns was the unfair treatment Black women, including herself, faced on public transportation. This issue was very important in her fight for women's right to vote.

In the 1860s and later, Harper gave many speeches about women's issues, especially those affecting Black women. One famous speech was "We Are All Bound Up Together," given in 1866 at the National Women's Rights Convention in New York City. In this speech, she demanded equal rights for everyone. She stressed the need to raise awareness for both African-American men's right to vote and women's right to vote.

After her speech, the National Woman's Rights Convention decided to form the American Equal Rights Association (AERA). This group included African-American suffrage in the Women's Suffrage Movement. Harper was on AERA's Finance Committee. However, Black women made up only a small number of the group's leaders and speakers.

AERA did not last long. It ended when Congress suggested the Fifteenth Amendment. This amendment would give African-American men the right to vote. Some suffragists, like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, did not support this amendment because it did not also give women the right to vote. But Harper supported the Fifteenth Amendment. She believed it was important progress for Black men.

After AERA split, Harper helped found the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), which supported the Fifteenth Amendment. She did not want to stop the progress of Black men by only fighting for women's suffrage. However, Harper also supported the idea of a Sixteenth Amendment, which would have given women the right to vote. After the Fifteenth Amendment passed in 1870, Harper encouraged formerly enslaved people to vote.

Harper also continued her work for women's suffrage by helping to found the National Association for Colored Women (NACW) in 1896. Often, Harper was the only Black woman at the progressive meetings she attended. This made her feel alone among mostly white reformers. So, she helped create the NACW to avoid the racism she sometimes faced from white activists. In 1897, Harper became the NACW's vice president. She used this role to advocate for Black women's civil rights.

Suffrage in Her Writings

Many of Harper's writings include themes about the right to vote. Her poem, "The Deliverance," published in her 1872 book Sketches of Southern Life, talks about voting through the stories of fictional Black women during the Reconstruction era. In this poem, Harper shows how women at home can inspire political change. She also presents women as moral guides and centers of power within the home.

Harper was concerned about how people would use their right to vote once they had it. "The Deliverance" shows these feelings through stories of different fictional men using their right to vote. For example, she writes about John Thomas Reeder, who "sold his vote / For something good to eat." His wife, Aunt Kitty, gets very upset. She throws the food away and scolds him, making him cry. Aunt Kitty shows her power in this scene, even though Reeder has the power of the vote. In "The Deliverance," Harper shows her desire for Black women to get voting rights alongside Black men.

Harper's poem, "The Fifteenth Amendment," describes the Fifteenth Amendment in a positive way. This amendment gave African-American men the right to vote:

"Ring out! ring out! your sweetest chimes, Ye bells, that call to praise; Let every heart with gladness thrill, And songs of joyful triumph raise.

Shake off the dust, O rising race! Crowned as a brother and a man; Justice to-day asserts her claim, And from thy brow fades out the ban.

With freedom's chrism upon thy head, Her precious ensign in thy hand, Go place thy once despised name Amid the noblest of the land"

In these lines, Harper uses exciting language and imagery. She talks about "sweetest chimes" and "joyful triumph." She tells African Americans to "shake off the dust." She also uses royal words to describe the newly enfranchised people. Black men are "crowned" and become "amid the noblest of the land." This is a strong contrast to their "once despised name." The poem shows Harper's strong support for the Fifteenth Amendment. Unlike "The Deliverance," this poem does not specifically mention Black women's right to vote.

Harper's novels also show her activism for suffrage. Her novel Minnie’s Sacrifice, published in 1869 (the same year as the Fifteenth Amendment debates), shows how voting could protect Black women from violence in the Reconstruction South. Minnie's Sacrifice also highlights the many challenges Black women faced. In this novel, Harper shows her strong desire for Black women to gain the right to vote.

Personal Life

In 1860, Frances Watkins married Fenton Harper, a widower. They had a daughter named Mary Frances Harper. Fenton Harper also had three other children from his previous marriage. When Fenton Harper died four years later, Frances Harper kept custody of Mary. They moved to the East Coast and lived there for the rest of their lives. Frances continued to give lectures to support herself.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper passed away from heart failure on February 22, 1911, at age 85. Her funeral was held at First Unitarian Church in Philadelphia. She was buried in Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, Pennsylvania, next to her daughter, Mary.

Selected Works

- Forest Leaves, verse, 1845

- Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects, 1854

- Free Labor, 1857

- The Two Offers, 1859

- Moses: A Story of the Nile, 1869

- Sketches of Southern Life, 1872

- Light Beyond the Darkness, 1890

- The Martyr of Alabama and Other Poems, 1894

- Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted, novel, 1892

- Idylls of the Bible, 1901

- In Memoriam, Wm. McKinley, 1901

Also, the following three novels were first published in parts in the Christian Recorder magazine between 1868 and 1888:

- Minnie's Sacrifice

- Sowing and Reaping

- Trial and Triumph

Legacy and Honors

- Many African-American women's service clubs are named after her. In cities like St. Louis, St. Paul, and Pittsburgh, groups like F. E. W. Harper Leagues and Frances E. Harper Women's Christian Temperance Unions were active for many years.

- A historical marker was placed at her home at 1006 Bainbridge Street, Philadelphia, to honor her.

- A dormitory at Morgan State University in Baltimore, Maryland, is named for her and Harriet Tubman. It is often called Harper-Tubman or simply Harper.

- A part of her poem "Bury Me in a Free Land" is written on a wall in the Contemplative Court at the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. The words are: "I ask no monument, proud and high to arrest the gaze of the passers-by; all that my yearning spirit craves is bury me not in a land of slaves."

- Her poem "Bury Me in a Free Land" was read in Ava DuVernay's film August 28: A Day in the Life of a People. This film was shown at the opening of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2016.

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Frances Harper para niños

In Spanish: Frances Harper para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |