Freedmen's Bureau facts for kids

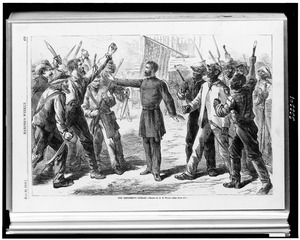

The Freedmen's Bureau was a special U.S. government agency created after the American Civil War. Its main job was to help millions of formerly enslaved people, known as freedmen, and poor white refugees in the Southern states. It started on March 3, 1865, and worked until 1872. The Bureau provided food, clothes, and shelter to those who had lost everything because of the war. It also helped freedmen and their families start new lives.

Contents

How the Bureau Started and What It Did

The Freedmen's Bureau was created by a law passed in 1865. U.S. President Abraham Lincoln had wanted this agency to help people after the war. It was meant to last for one year after the Civil War ended. The Bureau became part of the United States Department of War because that department had money and people already in the South.

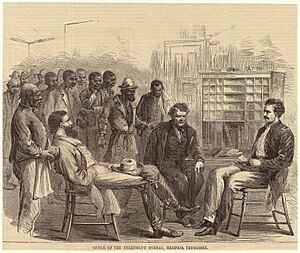

General Oliver Otis Howard led the Bureau, and it began its work in 1865. The Bureau faced many challenges. Southern states passed "Black Codes" which were unfair laws that limited the freedom of African Americans. These laws made it hard for freedmen to move around or work freely, almost like slavery again. Also, the Bureau had only a small amount of farmland to give out.

The Bureau's tasks grew over time. It helped African Americans find family members they had lost during slavery. It also taught them to read and write, which was very important to the freedmen and the government. Bureau agents also helped African Americans in court, especially with family issues. The Bureau encouraged former plantation owners to rebuild their farms and pay wages to their workers instead of using enslaved labor. It also checked the work contracts between freedmen and planters, since many freedmen could not read. The goal was to help white and Black people work together as employers and employees.

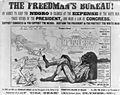

In 1866, Congress wanted to keep the Bureau going. But President Andrew Johnson disagreed. He said the Bureau interfered with "states' rights" (the idea that states should have more power than the federal government). He also felt it gave Black people help that poor white people didn't get. He thought it would make freed slaves too dependent on the government. Even though Congress voted to keep the Bureau despite Johnson's objections, its funding was cut by 1869. This meant the Bureau had to let go of many staff members. By 1870, the Bureau became even weaker because of violence from groups like the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). The KKK attacked Black people and white Republicans who supported them, including teachers. Some politicians also said the Bureau would make African Americans "lazy."

In 1872, Congress suddenly decided to close the Bureau. General Howard, who was away on another assignment, was not even told. The Bureau was closed because many Northerners were tired of the effort needed for Reconstruction. They also saw a lot of violence in the South and wanted the Southern states to manage themselves.

What the Bureau Achieved

Helping People Daily

The Bureau's main goal was to help newly freed slaves with everyday problems. This included getting food, medical care, finding family, and jobs. Between 1865 and 1869, the Bureau gave out 15 million food portions to freed African Americans and 5 million to poor white people. It also created a system for plantation owners to borrow food to feed their workers.

The Bureau's efforts to provide medical care were not very successful. Few white doctors in the South would treat freedmen. Also, much of the South's buildings and roads were destroyed, making it hard to improve health conditions. Diseases like cholera and yellow fever spread easily and caused many deaths, especially among the poor.

Family Life

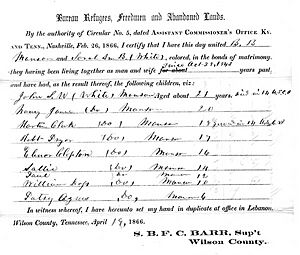

Before the Civil War, enslaved people could not legally marry. After the war, the Freedmen's Bureau helped many freed couples get legally married. Since many families had been separated during slavery, Bureau agents also helped them find each other. The Bureau had a system to send messages between agents to help reunite families. Sometimes, it even helped pay for transportation so families could be together again.

Education

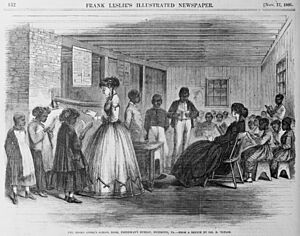

The Freedmen's Bureau is best known for its work in education. Before the Civil War, Southern states did not have public schools for everyone. Most states also made it illegal for Black people, both enslaved and free, to learn to read and write. Freedmen really wanted to learn. Some had already started schools in refugee camps even before the Bureau arrived.

General Oliver Otis Howard, the Bureau's leader, helped set up schools. He used buildings and supplies that had been taken from Confederate property to create schools for freedmen. He also helped teachers travel and find places to live. Many teachers from the North came South to teach the freedmen.

By 1866, groups from the North, like the American Missionary Association, worked with the Bureau to provide education. These groups raised money for teachers and managed schools. Congress also gave some money to the schools. The Bureau used its power to take Confederate property to help fund education.

George Ruby, an African American, worked as a teacher and inspector for the Bureau. He visited schools, helped set up new ones for Black students, and checked on Bureau officers. Black communities supported him, but many white people opposed him.

The Bureau spent $5 million to create schools for Black people. By the end of 1865, over 90,000 former slaves were going to these public schools. About 80% of students regularly attended. In 1868, General Samuel C. Armstrong started Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, which is now Hampton University.

The Freedmen's Bureau even published its own textbooks. These books taught reading and writing. They also included stories about Abraham Lincoln, parts of the Bible about forgiveness, and biographies of famous African Americans who showed humility and hard work.

By 1870, there were over 1,000 schools for freedmen in the South. An inspector for the Bureau wrote that freedmen had a "natural thirst for knowledge." Both children and adults wanted to learn. After the Bureau closed, some of its schools faced violence from white groups. Even though many Southern states created public education systems during Reconstruction, white politicians who later regained power reduced funding for Black schools. Laws like Jim Crow laws also created separate, underfunded schools for Black students.

By 1871, people in the North were less interested in helping the South. They were tired of the problems and violence. Northern groups then started to focus their money on colleges for African-American leaders instead of elementary schools.

Teachers and Colleges

Early historians thought most Bureau teachers were white women from the North. But new research shows that about half the teachers were Southern white people, one-third were Black (mostly from the South), and only one-sixth were Northern white people. Many teachers were men, and most were motivated by salary. Black teachers showed the strongest commitment to racial equality and often stayed teachers longer.

The Bureau and other groups also helped create colleges for African Americans. Leaders like Samuel C. Armstrong of Hampton Institute and Booker T. Washington of Tuskegee Institute believed that Black students needed higher education. These colleges aimed to provide a good education and teach students how to live successful, moral lives.

Lasting Impact on Education

Even though the Freedmen's Bureau closed, it had a big impact on the creation of historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). These schools became very important for Black students in the South during segregation. From 1866 to 1872, the Bureau and the American Missionary Association helped establish about 25 colleges for Black youth. Many of these schools, like Howard University, Fisk University, and Clark Atlanta University, are still strong institutions today.

Today, there are about 105 HBCUs. They educate over 50% of African-American professionals and public school teachers. They also graduate 70% of African-American dentists. Many African Americans who get degrees in science and math earned them at HBCUs. Howard University, founded in Washington, D.C., in 1867, was named after General Oliver Otis Howard, the head of the Freedmen's Bureau.

Church Establishment

After the Civil War, many Black people wanted to have their own churches, free from white control. Independent Black church groups, like the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and African Methodist Episcopal Zion churches, sent missionaries to the South. They helped freedmen start new churches. Within ten years, these Black churches gained hundreds of thousands of new members.

Freedmen also left white-led Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches. They quickly formed their own Black Baptist groups at the state and national levels. Northern church groups raised money to help build these new churches and schools, and to pay teachers.

Challenges and End of the Bureau

Bureau agents often tried to handle cases involving Black people in their own courts because they knew freedmen would not get fair trials in regular Southern courts. White Southerners argued that this was against the law. In some areas, like Louisiana's Caddo and Bossier parishes, white hostility was very high. Bureau agents faced many difficulties, and investigations were blocked by plantation owners. Murders of freedmen were common, and white suspects were rarely punished.

The Bureau struggled against this violence. In March 1872, General Howard was asked to leave his job temporarily to deal with Native American issues in the West. When he returned in November 1872, he found that Congress had officially closed the Bureau in June. President Johnson's opposition had encouraged many white Southerners to challenge the Bureau. Armed white groups continued to attack Black Republicans and their supporters. Congress closed the Bureau in 1872 due to pressure from white Southerners. The Bureau could not change the deep-seated social problems, as white people continued to try to control Black people, often with violence.

General Howard was very disappointed that Congress closed the Bureau without him being there. He said he would have preferred to close it himself. All of the Bureau's documents were moved to the War Department.

Bureau Records

In 2000, a law was passed to protect the Freedmen's Bureau records. These records are now being put online so people can easily search them. They include information from the Bureau's main office, field offices, marriage records, and more. These records are a huge help for understanding the Reconstruction Era and for African Americans researching their family history.

The Freedmen's Bureau Project, started in 2015, is a partnership between FamilySearch International and other groups like the National Archives and Records Administration and the Smithsonian. Volunteers help by looking at scanned documents and typing in names and dates. Once finished, millions of African Americans will be able to find information about their ancestors and build their family trees.

In 2006, Virginia became the first state to organize and put its Freedmen's Bureau records online.

Images for kids

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |