National Women's Rights Convention facts for kids

The National Women's Rights Convention was a series of yearly meetings. These meetings helped make the early women's rights movement in the United States more visible. The first meeting happened in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts.

These conventions included both women and men as leaders. They also gained support from many groups, like people who wanted to stop alcohol use (temperance advocates) and those who wanted to end slavery (abolitionists). Speakers talked about many important topics. These included equal pay, better education, more job chances, women's property rights, changes to marriage laws, and temperance. A main goal discussed at the convention was getting laws passed that would give women the right to vote.

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

How the Movement Began

The Seneca Falls Convention

In 1840, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton traveled to London. They went with their husbands to the first World Anti-Slavery Convention. But they were not allowed to join in because they were women. Mott and Stanton became friends there. They decided to organize a meeting to help women gain more rights.

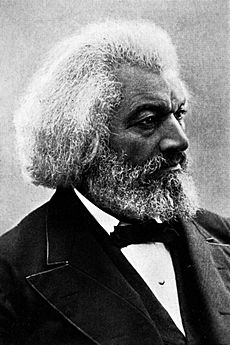

In the summer of 1848, Mott, Stanton, and three other women organized the Seneca Falls Convention. This was the very first women's rights convention. About 300 people attended over two days, including about 40 men. A proposal about women's right to vote caused some disagreement. But then Frederick Douglass gave a powerful speech. He spoke in favor of including a statement about voting rights in their plan, called the Declaration of Sentiments. One hundred people at the meeting then signed the Declaration.

Other Early Women's Rights Meetings

Those who signed the Declaration hoped for more meetings across the country. Because Lucretia Mott was very famous, some people from Seneca Falls organized another meeting just two weeks later. This was the Rochester Women's Rights Convention of 1848. Many of the same speakers attended. The first women's rights meeting organized for a whole state was the Ohio Women's Convention at Salem in 1850.

Planning the National Convention

In April 1850, women in Ohio held a meeting. They wanted to ask their state to give women equal legal and political rights. Lucy Stone had been speaking about women's rights since 1847. She wrote to the Ohio organizers, promising that Massachusetts would follow their lead.

On May 30, 1850, a meeting was held in Boston to decide if a women's rights convention should take place. Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis led this meeting. Lucy Stone was the secretary. They decided to hold a convention in Worcester, Massachusetts, on October 16 and 17, 1850. They formed a committee to arrange everything.

Davis and Stone asked William Elder to write the official invitation for the convention. They worked to get signatures and speakers. Elizabeth Cady Stanton sent a letter of support and a speech to be read. She could not attend because she was pregnant. Lucy Stone also faced challenges, including a family illness. Despite these difficulties, the invitation began to circulate in September. Lucy Stone's name was at the top of the list of 89 signers from many states.

The First National Convention: 1850 in Worcester

The first National Women's Rights Convention took place in Brinley Hall in Worcester, Massachusetts. It was held on October 23–24, 1850. About 900 people came to the first session. Most of them were men. Newspapers reported over a thousand attendees by the afternoon of the first day. Many people were even turned away. Delegates came from eleven states, including California, which was a very new state.

Sarah H. Earle, a leader in Worcester's anti-slavery groups, started the meeting. Paulina Wright Davis was chosen to lead the convention. In her opening speech, she called for "the freedom of a group, the saving of half the world." She also asked for a new way of organizing all social, political, and work-related interests.

The first goal of the movement was stated: to give women "political, legal, and social equality with man." This meant women should have the same rights as men. Another goal was to remove the word "male" from every state's constitution. Other proposals focused on specific issues. These included property rights, access to education, and job opportunities. The movement also aimed to secure the "natural and civil rights" of all women, including enslaved women.

The convention discussed how to organize to reach their goals. They decided that yearly conventions and a committee to plan them would be enough. They did not need a formal organization. A committee of nine women and nine men was chosen. Other committees were formed to gather information. This information would help guide public opinion toward giving "Woman's co-equal sovereignty with Man."

Many important people spoke at the convention. These included William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, Harriot Kezia Hunt, Ernestine Rose, Antoinette Brown, Sojourner Truth, Lucretia Mott, and Frederick Douglass. Lucy Stone spoke on the final evening. She urged people to ask their state governments for the right to vote. She also asked for married women to own property and other specific rights. She said, "We want to be something more than just parts of Society." She added, "We want Woman to be equal to Man in all parts of human life."

Susan B. Anthony was not at this convention. But she later said that reading Lucy Stone's speech made her join the women's rights cause. Lucy Stone paid to have the convention's speeches printed as booklets. She sold these booklets at her lectures and at future conventions.

The report of the convention in the New York Tribune for Europe inspired women in England. It led them to ask for women's right to vote. It also inspired Harriet Taylor Mill to write The Enfranchisement of Women in 1851.

1851 in Worcester

A second national convention was held on October 15–16, 1851. It was again in Brinley Hall. Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis led the meeting. Harriet Kezia Hunt and Antoinette Brown gave speeches. A letter from Elizabeth Cady Stanton was read. Lucretia Mott helped lead the meeting.

Wendell Phillips gave a very convincing speech. It was so powerful that it was sold as a pamphlet until 1920. He said, "Open the doors of Congress; open those court-houses; throw wide open the doors of your colleges." He urged people to give women the same chances for learning that men have.

Elizabeth Oakes Smith, a writer, attended the 1850 convention. In 1851, she was asked to speak. Afterward, she wrote articles for the New York Tribune defending the convention.

Abby Kelley Foster shared her experiences of being treated unfairly as a woman. She said, "My life has been my speech. For fourteen years I have supported this cause by my daily life."

A letter was read from two French women who were in prison. They said, "Your brave declaration of Woman's Rights has reached our prison, and has filled our souls with great joy."

Ernestine Rose gave a speech about how women lose their identity when they marry. She said that a woman "loses her entire identity" when she marries. Rose questioned why a woman is expected to be completely submissive. She argued that "Blind submission in women is considered a virtue, while submission to wrong is itself wrong."

1852 in Syracuse

The third convention was held at the city hall in Syracuse, New York. Syracuse was closer to Seneca Falls. This meant more of the original signers of the Declaration of Sentiments could attend. Lucretia Mott was chosen as president. She even had to quiet a minister who used the Bible to say women should be below men.

A letter from Elizabeth Cady Stanton was read. Her ideas were voted on. At the meetings on September 8–10, 1852, Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage gave their first public speeches on women's rights. Ernestine Rose spoke about duties without rights. She said that since women pay taxes, they should have a right to help form and run the government.

Antoinette Brown asked for more women to become ministers. She said the Bible did not forbid it. Ernestine Rose disagreed. She said the Bible should not be the only authority, as it had many contradictions about women. Elizabeth Oakes Smith called for women to have their own newspaper. She wanted them to be independent of male-owned newspapers.

Lucy Stone wore a trousered dress, often called "bloomers." She said, "The woman who first leaves the usual path must suffer." She encouraged women to "bravely bear ridicule and persecution." The Syracuse Weekly Chronicle was very impressed by her speech.

Reverend Lydia Ann Jenkins asked, "Is there any law to prevent women from voting in this State?" She pointed out that the Constitution said "white male citizens" could vote. But it did not say white female citizens could not. The next year, Jenkins helped create the issue of suffrage for the New York State Legislature.

A proposal was made to form a national organization for women. But after much discussion, no agreement was reached. Many leaders, including Lucretia Mott and Wendell Phillips, felt that organizations could cause problems. No national organization was formed until after the American Civil War.

1853 in Cleveland

At Melodeon Hall in Cleveland, Ohio, on October 6–8, 1853, William Lloyd Garrison spoke. He said that the Declaration of Independence from Seneca Falls was "measuring the people of this country by their own standard." It was using their own words and ideas to apply to women, just as they had been applied to men.

Earlier that year, a meeting in New York City had been interrupted by rude men. Organizers of the fourth national convention worried this might happen again. But in Cleveland, discussions were orderly.

Frances Dana Barker Gage led the meeting for 1,500 people. Lucretia Mott, Amy Post, and Martha Coffin Wright also helped lead.

William Henry Channing suggested that the convention create its own Declaration of Women's Rights. He also suggested petitions to state governments asking for women's right to vote, equal inheritance rights, and other rights. The Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments was read and discussed. A committee was formed to write a new declaration, but it was never officially adopted.

The Plain Dealer newspaper wrote a long report about the convention. They said Ernestine Rose "is the master-spirit of the Convention." They also commented on Lucy Stone's bloomer costume. They called Miss Stone "a lady of no common abilities."

1854 in Philadelphia

At Sansom Street Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from October 18–20, 1854, Ernestine Rose was chosen president. This was despite her being an atheist. Susan B. Anthony supported her, saying everyone should have an equal right to speak. Rose told the group, "Our claims are based on that great and unchanging truth, the rights of all humanity." She asked, "is woman not included in that phrase, 'all men are created ... equal'?"

Susan B. Anthony urged attendees to ask their state governments for laws giving women equal rights. A committee was formed to publish articles in newspapers. Again, the convention could not agree to create a national organization. They decided to continue working locally.

Henry Grew spoke to criticize women who demanded equal rights. He used examples from the Bible to say women should be in a lower role. Lucretia Mott argued with him. She said he was using the Bible unfairly. She said the Bible had been "ill-used." William Lloyd Garrison stopped the debate. He said almost everyone agreed that all people were equal in God's eyes.

1855 in Cincinnati

At Smith & Nixon's Hall in Cincinnati, Ohio, on October 17–18, 1855, Martha Coffin Wright led the meeting. The hall was completely full. Wright, who was Lucretia Mott's younger sister, compared the large crowd to the much smaller meeting in 1848. That first meeting was held "in fear and doubt of our own strength."

Antoinette Brown, Ernestine Rose, Josephine Sophia White Griffing, and Frances Dana Barker Gage spoke. They listed the progress made so far. Lucy Stone spoke about the right of each person to decide their own role in life. A person in the crowd interrupted, calling the female speakers "a few disappointed women." Stone replied with a famous answer. She said yes, she was a "disappointed woman." She added, "In education, in marriage, in religion, in everything, disappointment is the lot of woman." She promised to "deepen this disappointment in every woman's heart until she bows down to it no longer."

1856 in New York

At the Broadway Tabernacle in New York City on November 25–26, 1856, Lucy Stone was president. She told the crowd about new laws. These laws gave women more property rights in nine states. Widows in Kentucky could also vote for school board members. She was happy that the new Republican Party was interested in women helping in the 1856 elections. Lucretia Mott told the group to use their new rights.

A letter from Antoinette Brown Blackwell was read. She suggested that the National Convention should demand the right to vote for women from each state's government. A motion was passed to approve this idea. Wendell Phillips suggested contacting women in each state. They would be encouraged to take this petition to their state governments.

1858 in New York

For the eighth and later national conventions, the meetings changed from autumn to mid-May. The year 1857 was skipped. The next meeting was held on May 13–14, 1858, at Mozart Hall in New York City. Susan B. Anthony was the president. William Lloyd Garrison spoke. He said, "Those who have started this movement are worthy to be ranked with the army of heroes." He hoped they would win, and that "peace and love, justice and liberty, might prevail throughout the world." Garrison even suggested that the number of female lawmakers should be equal to male lawmakers.

Frederick Douglass spoke after many requests from the audience. Lucy Stone, Reverend Antoinette Brown Blackwell, Reverend Thomas Wentworth Higginson, and Lucretia Mott also spoke. Eliza Farnham shared her idea that women were better than men. This idea was debated a lot. The convention was interrupted and ended in "great confusion."

1859 in New York

The ninth national convention was held again at Mozart Hall in New York City on May 12, 1859. Lucretia Mott led the meeting. Caroline Wells Healey Dall read out the proposals. One proposal was to be sent to every state government. It urged them to "secure to women all those rights and privileges ... which belong to every citizen."

Another unruly crowd made it hard to hear the speeches. Antoinette Brown Blackwell, Caroline Dall, Lucretia Mott, and Ernestine Rose spoke. Wendell Phillips spoke and "held that mocking crowd in the hollow of his hand."

1860 in New York

At the Cooper Union in New York City on May 10–11, 1860, the tenth national convention took place. Martha Coffin Wright led the meeting, with 600–800 people attending. A recent win in New York law was praised. It gave women shared custody of their children. It also gave them full control of their personal property and earnings.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Antoinette Brown Blackwell suggested adding a proposal about marriage reform. They wanted laws that would let women separate from or divorce a husband who was cruel or had deserted them. Wendell Phillips argued against this idea. Susan B. Anthony supported it. But after a heated debate, the proposal was defeated by a vote.

Horace Greeley wrote in the Tribune that there were "One Thousand Persons Present, seven-eighths of them Women." Greeley, who was against marriage reform, criticized Stanton's idea.

After the Civil War

The start of the American Civil War stopped the yearly National Women's Rights Convention. Women's efforts then focused on ending slavery (emancipation). The New York state government even took away many of the gains women had made in 1860. Susan B. Anthony was very upset. But she could not convince women activists to hold another convention focused only on women's rights.

In 1863, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony called for women to meet again. They formed the Woman's National Loyal League. This group included Stanton, Anthony, Martha Coffin Wright, Lucy Stone, and others. They organized a convention in New York City on May 14, 1863. They worked to get 400,000 signatures by 1864. These signatures were for a petition to the United States Congress. The petition asked for the Thirteenth Amendment to be passed, which would abolish slavery.

1866 in New York

On May 10, 1866, the Eleventh National Women's Rights Convention was held. It was called by Stanton and Anthony. The meeting included Ernestine L. Rose, Wendell Phillips, Lucretia Mott, and others. Stanton led the meeting.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, an African-American activist, gave a powerful speech against racial unfairness. She said, "You white women speak here of rights. I speak of wrongs. I, as a colored woman, have had in this country an education which has made me feel as if I were in the situation of Ishmael, my hand against every man, and every man's hand against me."

A few weeks later, on May 31, 1866, the first meeting of the American Equal Rights Association took place in Boston.

1869 in Washington, D.C.

An event called "The twelfth regular National Convention of Women's Rights" happened on January 19, 1869. Important speakers included Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and others. Doctor Mary Edwards Walker and a "Mrs. Harman" were seen in "male attire" moving between the audience and the stage.

Stanton gave a strong speech against those who had created "an aristocracy of sex on this continent." She said, "If slavery has destroyed kingdoms ... what kind of a government, American statesmen, can you build, with the mothers of the race crouching at your feet ... ?" Other speeches were not planned, and little is known about them.

| National Women’s Rights Convention (1850

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |