Lucy Stone facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lucy Stone

|

|

|---|---|

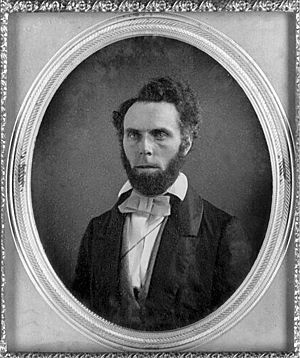

Daguerreotype of Lucy Stone, circa 1840–1860

|

|

| Born | August 13, 1818 West Brookfield, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Died | October 18, 1893 (aged 75) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Bachelor of Arts |

| Alma mater | Oberlin College |

| Known for | Abolitionist suffragist women's rights activist |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Alice Stone Blackwell |

Lucy Stone (August 13, 1818 – October 18, 1893) was a very important American speaker, who fought to end slavery and gain voting rights for women. She was a strong voice for women's rights. In 1847, Lucy Stone became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a college degree. She was also famous for keeping her own last name after she got married, which was very unusual at the time.

Lucy Stone worked hard to make real changes for women's rights in the 1800s. She helped start the first National Women's Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. She also supported this meeting every year, along with many other local and state meetings. Stone spoke to lawmakers to help pass laws that would give women more rights. She helped create the Women's Loyal National League to support the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery. After that, she helped form the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). This group worked to get women the right to vote at state and local levels.

Stone wrote a lot about women's rights. She published speeches by herself and others, and reports from conventions. She founded a weekly newspaper called the Woman's Journal, which was very important and lasted a long time. In it, she shared her own ideas and different views on women's rights. People called her "the orator" and the "morning star" of the women's rights movement. She even inspired Susan B. Anthony to join the fight for women's voting rights. Elizabeth Cady Stanton said that Lucy Stone was the first person to truly make Americans care about "the woman question." Together, Anthony, Stanton, and Stone are known as the three main leaders of women's suffrage and feminism in the 1800s.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Life at Oberlin College

- Early Activism

- National Women's Rights Convention

- A Powerful Speaker for Women's Rights

- Stepping Back and Returning to Activism

- National Organizations for Rights

- Working for the Vote

- Coming Together and Final Years

- Last Public Appearances

- Legacy and Remembrance

- Lucy Stone's Home

- See also

Early Life and Education

Lucy Stone was born on August 13, 1818, on her family's farm in West Brookfield, Massachusetts. She was one of nine children. Her family worked hard on the farm. Lucy remembered her childhood as a time when they had plenty of food.

Lucy's father controlled all the family's money, which was common then. Her mother earned some money selling eggs and cheese but couldn't control it. Lucy saw this as unfair. She later realized that old customs were to blame. This made her believe that customs needed to change to be fair.

From her mother and other women she knew, Lucy learned that women depended on their husbands. When she read a Bible verse that seemed to say husbands should rule over wives, she was upset. She decided she would never marry, get the best education she could, and earn her own living. She wanted to control her own life.

Teaching for "Woman's Pay"

At age 16, Lucy Stone started teaching in schools. She was paid much less than male teachers. When she filled in for her brother, she still got less pay than he did. When she complained, the school committee said they could only give her "a woman's pay." This lower pay for women was a reason some people wanted to hire women teachers. They thought women would teach for less money. Even as her salary increased, it was always lower than what men earned.

The "Woman Question"

Around 1836, Stone started reading about a big debate in Massachusetts. People called it the "woman question." They wondered what women's role in society should be. Should women be active in public reform movements?

This debate grew when women sent many anti-slavery petitions to Congress. They were rejected partly because women sent them. Women abolitionists then held a meeting in New York City. They said that all people have certain rights and duties. They would not stay within limits set by "corrupt custom." When sisters Angelina and Sarah Grimké spoke to mixed groups of men and women, it caused a stir. Ministers condemned women speaking in public. Stone was at this meeting and was very angry. She decided that if she ever had something to say in public, she would say it.

Stone read Sarah Grimké's "Letters on the Province of Woman." She told her brother these letters made her even more determined "to call no man master." She used ideas from these letters in her college essays and later speeches.

Seeking Higher Education

Determined to get the best education, Stone went to Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in 1839. She was 21. But she was disappointed that the school didn't support anti-slavery or women's rights. She left after one term. The next month, she went to Wesleyan Academy, which she liked better. She reported that students there thought "ladies ought to mingle in politics, go to Congress, etc."

Stone read about Abby Kelley being denied the right to speak or vote at an anti-slavery meeting. Kelley bravely raised her hand every time a vote was taken. Stone admired her and wished there were more like her. Three years later, Stone followed Kelley's example. In 1843, a deacon was kicked out of Stone's church for supporting Kelley. When the church voted to expel him, Stone raised her hand to defend him. The minister ignored her vote, saying she wasn't a voting member. Like Kelley, Stone stubbornly raised her hand for every vote.

After a year at Monson Academy, Stone learned that Oberlin College in Ohio was the first college to admit women and give them degrees. Stone prepared by studying Latin and Greek.

Life at Oberlin College

In August 1843, at age 25, Lucy Stone traveled to Oberlin College in Ohio. It was the first college in the U.S. to admit both women and African Americans. Stone believed women should vote, hold political office, study important professions, and speak in public. Oberlin College did not fully agree with all these ideas.

In her third year, Stone became friends with Antoinette Brown. Brown was also an abolitionist and suffragist. She came to Oberlin to study to become a minister. Stone and Brown later married brothers, becoming sisters-in-law.

Fighting for Equal Pay

Stone hoped to pay for college by teaching at Oberlin. But as a first-year student, she could only do housekeeping chores. For this, she was paid three cents an hour. This was less than half what male students earned for their work. Stone often cooked her own meals to save money. In 1844, she got a teaching job but again received less pay because she was a woman.

Oberlin's rules meant Stone had to work twice as much as a male student to pay the same costs. She often woke up at 2 AM to work and study, and her health suffered. In February 1845, she decided she wouldn't accept this unfairness anymore. She asked the Faculty Board for the same pay as male teachers with less experience. When they said no, she quit. Her former students begged the faculty to rehire her. They said they would pay Stone "what was right" if the college wouldn't. After three months of pressure, the faculty gave in. They hired Stone back and paid her and other women student teachers the same as men.

Learning to Speak in Public

In 1846, Stone told Abby Kelley Foster she wanted to become a public speaker. A big debate about Foster speaking at Oberlin helped Stone decide. The faculty opposed Foster, which led to passionate discussions among students about women's right to speak in public. Stone strongly defended this right. She then gave her first public speech at Oberlin in August 1846.

In the fall of 1846, Stone told her family she planned to become a women's rights lecturer. Her brothers supported her, and her father encouraged her. But her mother and sister begged her to rethink. Stone told her mother she knew she might be disliked, but she had to do what she believed was best for the world.

Stone then worked to gain speaking experience. Women students could debate each other, but it was not allowed for them to speak with men in class. So, Stone and Antoinette Brown started an off-campus women's debating club. After practicing, they got permission to debate in Stone's rhetoric class. This debate attracted many students and caught the attention of the Faculty Board. They then banned women from speaking in coeducational classes.

Soon after, Stone debated a newspaper editor on women's rights and won. She then asked the Faculty Board to let women read their own graduation essays, just like men did. The board refused. When Stone was chosen to write an essay, she declined. She said she could not support a rule that denied women the chance to work alongside men in any area where they had the ability.

Lucy Stone received her college degree from Oberlin College on August 25, 1847. She was the first woman from Massachusetts to graduate from college.

Early Activism

Lucy Stone gave her first public speeches on women's rights in the fall of 1847. She spoke in her brother's church in Gardner, Massachusetts, and later in Warren. In June 1848, she became a speaker for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. Abby Kelley Foster convinced her that this would give her the speaking practice she needed for her women's rights work. Stone quickly became a powerful speaker. People said she had an amazing ability to persuade her audiences. She was described as a "meek-looking Quakerish body" with "sweetest, modest manners" but as "unshrinking and self-possessed as a loaded cannon." Her voice was often compared to a "silver bell."

Her anti-slavery work helped Stone meet other reformers. In 1848, she was invited to lecture for the women who organized the Seneca Falls Convention and the Rochester Women's Rights Convention of 1848. These meetings helped the women's rights movement grow. Famous leaders like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Lucy Stone met and worked together. They wrote, discussed, and circulated petitions for women's rights.

In April 1849, Stone was invited to speak for the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Lucretia Mott used this chance to hold Pennsylvania's first women's rights meeting. With help from abolitionists, Stone led Massachusetts' first campaigns to get women the right to vote and hold public office. Wendell Phillips wrote the first petitions, and William Lloyd Garrison published them in The Liberator. By February 1850, over half the petitions Stone sent to the legislature were from towns where she had lectured.

National Women's Rights Convention

In April 1850, the Ohio Women's Convention asked that the new state constitution give women the same rights as men. Stone sent a letter praising their efforts. She said Massachusetts should have led the way, but if it was slow, the "young sisters of the West" could set an example.

Before this, women's rights meetings were regional or state-based. In 1850, during an anti-slavery meeting in Boston, Stone and Paulina Wright Davis suggested organizing a national women's rights convention. They held a meeting in Boston, where Stone presented the idea. Seven women were chosen to organize the convention.

A few months before the convention, Stone became very ill with typhoid fever. This left Davis as the main organizer of the first National Women's Rights Convention. It met on October 23–24, 1850, in Worcester, Massachusetts, with about a thousand people attending. Stone was able to go but was too weak to give a formal speech until the end.

The convention decided not to form a permanent group but to hold annual meetings. Stone was appointed to the Central Committee. She became its secretary the next spring and held that job until 1858. As secretary, Stone played a key role in organizing the national conventions throughout the 1850s.

A Powerful Speaker for Women's Rights

In May 1851, while in Boston, Lucy Stone saw Hiram Powers's statue The Greek Slave. She was so moved that she spoke about it that evening. She said the statue showed how women were "enchained." When a leader from the anti-slavery society criticized her for speaking about women's rights at an anti-slavery meeting, she replied, "I was a woman before I was an abolitionist. I must speak for women." Three months later, Stone decided to lecture full-time on women's rights.

She started her career as an independent women's rights speaker on October 1, 1851. She still lectured for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society on Sundays. She used the money from her anti-slavery work to pay for her women's rights lectures until she could charge admission.

Dress Reform

In 1851, Stone started wearing a new style of dress. It had a loose, short jacket and baggy trousers under a skirt that went a few inches below the knees. This dress was part of a health reform movement. It was meant to replace the popular French dress, which had a tight corset and a long, heavy skirt. Many women across the country had started wearing similar outfits.

In March 1851, Amelia Bloomer, a newspaper editor, announced she was wearing this dress and printed instructions to make it. Soon, newspapers called it the Bloomer dress. The Bloomer became a popular trend. Stone wore the Bloomer dress when she lectured. For many in her audience, it was the first time they had seen one. However, the dress became controversial. Newspapers first praised it but then started to make fun of it. They saw the trousers as women trying to take on male authority. Many women stopped wearing it, but Stone continued for three years. She also wore her hair short.

Stone found the short skirt helpful for traveling. She defended it against those who said it hurt the women's rights cause. However, she disliked the attention it drew. In 1854, she started wearing a slightly longer dress sometimes. In 1855, she stopped wearing the Bloomer dress completely.

Church Expulsion

Stone often criticized churches that did not condemn slavery. Her own church in West Brookfield had already expelled a deacon for his anti-slavery work. In 1851, the church expelled Stone herself. Stone had also changed her religious beliefs, becoming a Unitarian. After being expelled, she joined a Unitarian church.

Marriage and Personal Choices

Before her own marriage, Stone believed women should be able to divorce husbands who were abusive or in loveless marriages. She wanted women to have control over their own lives. However, she worked to keep the topic of divorce separate from the main women's rights platform. She wanted to avoid the idea that the movement supported loose morals. She focused on women's right to control their own bodies and lives.

In 1853, Henry Browne Blackwell, a businessman who supported women's rights, began to court Lucy Stone. Stone told him she did not want to marry because she didn't want to lose control over her life. She also didn't want to take on the legal position of a married woman at the time. Blackwell argued that they could create an equal partnership. They could also protect her assets. He believed marriage would help them both achieve more. He even arranged a successful lecture tour for Stone in the western states to show his support. After 18 months of letters, Stone fell in love and agreed to marry him in November 1854.

Stone and Blackwell made a private agreement to protect Stone's financial independence and personal freedom. They agreed their marriage would be like a business partnership. Neither would control the other's property or earnings from before the marriage. They would share earnings while married. Each would have personal independence. They agreed that neither would try to control the other's home, job, or habits. Blackwell also agreed that Stone would decide "when, where and how often" she would "become a mother."

As part of their wedding ceremony, Blackwell also made a public protest against laws that gave husbands more rights. He promised never to use those laws. Their wedding took place on May 1, 1855. Their protest was published in newspapers across the country. It inspired other couples to make similar protests.

Keeping Her Name

Lucy Stone believed that wives taking their husband's last name showed that a married woman lost her own identity. After her marriage, with her husband's agreement, she continued to sign her name as "Lucy Stone." However, when Blackwell tried to register a property deed for Stone, the official insisted she sign as "Lucy Stone Blackwell." They sought legal advice. For eight months, she used "Lucy Stone Blackwell" on public papers. But once she learned no law required her to change her name, Stone publicly announced in May 1856 that her name remained Lucy Stone.

In 1879, when women in Boston could vote in school elections, Stone tried to register. But officials said she had to add "Blackwell" to her signature. She refused and could not vote. She did not challenge this in court because she was busy with suffrage work.

Children

Stone and Blackwell had one daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell, born in September 1857. Alice later became a leader in the suffrage movement and wrote her mother's first biography. In 1859, Stone had a miscarriage and lost a baby boy.

Stepping Back and Returning to Activism

After her marriage, Lucy Stone continued her busy schedule of lecturing and organizing until the summer of 1857. The birth of her daughter in September 1857, however, reduced her activism. Her daughter was often sick, and Stone wanted to stay home to care for her. Stone eventually stepped back from most public work. She resigned from the committee that organized the annual women's rights conventions. She made only two public appearances during the American Civil War (1861–1865).

As a believer in nonresistance, Stone could not support the war itself. But she strongly supported ending slavery, which the war made possible. In 1863, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony organized the Women's Loyal National League. This group collected nearly 400,000 signatures on petitions to abolish slavery. Stone agreed to lead the League's first meeting and later managed its office for two weeks.

In 1864, Henry Blackwell's real estate investments became very successful. This improved the family's finances greatly. Blackwell was able to spend more time on social reform. Stone slowly began to increase her public activities again. In the fall of 1865, she started a lecture tour on women's rights. By 1866, she was traveling with Blackwell on a joint lecture tour.

National Organizations for Rights

American Equal Rights Association

Slavery was abolished in December 1865. This led to questions about the future of the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS). In January 1866, Stone and Anthony suggested merging the anti-slavery and women's movements. They wanted one group to fight for equal rights for all citizens. The AASS refused, wanting to focus only on the rights of newly freed African Americans.

In May 1866, Anthony and Stanton organized the Eleventh National Women's Rights Convention. It was the first since the Civil War. The convention voted to become a new group called the American Equal Rights Association (AERA). Its goal was to campaign for equal rights for everyone, especially the right to vote. Stone was elected to the new group's executive committee.

In 1867, Stone and Blackwell led a difficult campaign in Kansas. They supported proposals to give both African Americans and women the right to vote. They worked for three months. However, voters did not approve either proposal. Disagreements during the Kansas campaign led to a growing split in the women's movement.

A Split in the Movement

The main reason for the split was the proposed Fifteenth Amendment. This amendment would stop states from denying the right to vote based on race. Anthony and Stanton campaigned against it. They insisted that women and African Americans should get the right to vote at the same time. They argued that by giving all men the vote but excluding all women, the amendment would create an "aristocracy of sex."

Stone supported the amendment. She had hoped that both African Americans and women would get the vote at the same time. She was upset when this didn't happen. In 1867, she wrote that it was a "terrible mistake" to give black men the vote first. She believed that "the safety of the government would be more promoted by the admission of woman." However, she still supported the amendment. She hoped that their support would lead abolitionist friends in Congress to push for women's voting rights next. But this did not happen.

Henry Blackwell, Stone's husband, also supported the amendment. He tried to convince southern politicians that giving women the vote would help keep white supremacy in their region. Stone's reaction to this idea is not known.

The AERA broke apart after a difficult meeting in May 1869. Two new women's suffrage groups were formed. Two days after the meeting, Anthony, Stanton, and their allies formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). In November 1869, Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe, and their allies formed the competing American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). The AWSA was larger at first but became weaker in the 1880s.

Even after the Fifteenth Amendment was passed in 1870, differences remained. The AWSA focused almost only on women's voting rights. The NWSA worked on many issues, including divorce reform and equal pay for women. The AWSA included both men and women leaders, while the NWSA was led only by women. The AWSA worked mostly at the state level, and the NWSA worked more at the national level. The AWSA tried to appear respectable, while the NWSA sometimes used more direct methods.

Views on Marriage Laws

In 1870, at the twentieth anniversary of the first National Women's Rights Convention, Stanton spoke for three hours about women's right to divorce. By then, Stone's views had changed. Stone wrote, "We believe in marriage for life, and dislike all this loose, harmful talk in favor of easy divorce." Stone made it clear that those who wanted "free divorce" were not part of her organization, the AWSA.

Working for the Vote

In 1870, Stone and Blackwell moved to Dorchester, Massachusetts, which is now part of Boston. They bought a large house there. Many women in Dorchester were already active in women's rights.

New England Woman Suffrage Association

At her new home, Stone worked closely with the New England Woman Suffrage Association (NEWSA). This was the first major political group in the U.S. focused on women's voting rights. Stone had helped found it and was elected to its executive committee. In 1877, she became its president and stayed in that role until she died in 1893.

Woman's Journal

In 1870, Stone and Blackwell started the Woman's Journal, an eight-page weekly newspaper in Boston. It was meant to share the ideas of the NEWSA and the AWSA. By the 1880s, it became the unofficial voice of the whole suffrage movement. Stone edited the journal for the rest of her life, with help from her husband and daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell. Stone did not take a salary for her work. She constantly had to raise money to keep it going. Its highest circulation was 6,000 copies.

When the AWSA and NWSA merged in 1890, the Woman's Journal became the official newspaper of the new group. In 1917, Carrie Chapman Catt, a leader of the suffrage movement, said the Woman's Journal was incredibly valuable. She said women's suffrage success was not possible without it.

The Colorado Lesson

In 1877, Stone was asked to help activists in Colorado organize a public vote to gain suffrage for women. Stone and Blackwell worked in the northern part of the state. Susan Anthony worked in the southern part. Support was mixed. Many Latino voters were not interested. Some blamed the strong opposition from the Roman Catholic bishop of Colorado. Most politicians ignored or fought the measure. Stone focused on convincing Denver voters, but the measure lost badly, with 68% voting against it. Married working men showed the most support. Blackwell called it "The Colorado Lesson." He wrote that women's suffrage could not be won by a popular vote without a political party supporting it.

School Board Voting Rights

In 1879, after Stone organized a petition, women in Massachusetts gained limited voting rights. A woman with the same qualifications as a male voter could vote for school board members. Lucy Stone applied to vote in Boston. But she was told she had to sign her husband's last name as her own. She refused and never voted in those elections.

Coming Together and Final Years

In 1887, 18 years after the split in the women's rights movement, Stone suggested merging the two groups. Plans were made, and by 1890, the organizations resolved their differences. They merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Stone was too weak from heart and breathing problems to attend its first meeting. But she was elected chair of the executive committee. Stanton was president, but Anthony was the practical leader.

In early 1891, Carrie Chapman Catt visited Stone many times to learn about political organizing. Stone had met Catt before and was impressed by her. Stone taught Catt a lot about lobbying and fundraising. Catt later used this knowledge to lead the final push to get women the vote in 1920.

In January 1892, Catt, Stone, and Blackwell went to the NAWSA convention in Washington, D.C. Stone, Stanton, and Anthony, the "triumvirate" of women's suffrage, were called to an unexpected hearing before Congress. Stone told the congressmen, "We are handicapped as women... by the single fact that we have no vote. This cheapens us. You do not care so much for us as if we had votes..." Stone argued that men should pass laws for equal property rights between men and women. She demanded an end to coverture, which meant a wife's property became her husband's. Stone's speech was followed by Stanton's brilliant one, which Stone later published. At the NAWSA convention, Anthony was elected president, and Stanton and Stone became honorary presidents.

Last Public Appearances

In 1892, Stone finally agreed to have a sculpture portrait made by Anne Whitney. She had protested for over a year, saying the money should be spent on suffrage work. In February 1893, Stone invited her brother to see the sculpture before it went to the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Stone went to Chicago with her daughter in May 1893. She gave her last public speeches at the World's Congress of Representative Women. She saw strong international involvement, with nearly 500 women from 27 countries speaking. Stone focused on upcoming votes in New York and Nebraska. She gave a speech called "The Progress of Fifty Years." In it, she said, "I think, with never-ending gratitude, that the young women of today do not and can never know at what price their right to free speech and to speak at all in public has been earned." Stone met with Carrie Chapman Catt to plan for organizing in Colorado. Stone and her daughter returned home on May 28.

Those who knew Stone well noticed her voice was weak. In August, she was too weak to attend more meetings at the Exposition. In September, she was diagnosed with advanced stomach cancer. She wrote final letters to friends and family. Lucy Stone died on October 18, 1893, at age 75. At her funeral, 1,100 people filled the church, and hundreds more stood outside. Six women and six men were pallbearers, including sculptor Anne Whitney and Stone's old friend Thomas Wentworth Higginson. Stone's death was the most widely reported of any American woman's up to that time.

According to her wishes, her body was cremated. She was the first person cremated in Massachusetts. Stone's remains are buried at Forest Hills Cemetery. A chapel there is named after her.

Legacy and Remembrance

Lucy Stone's refusal to take her husband's name was very controversial then. It is largely what she is remembered for today. Women who keep their maiden names after marriage are sometimes still called "Lucy Stoners" in the United States. In 1921, the Lucy Stone League was founded in New York City by Ruth Hale. The League was started again in 1997.

Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and others began writing the History of Woman Suffrage in 1876. Because of differences between Stone and Stanton, Stone's important role was not fully shown in this work. This book was used as the main source on 19th-century U.S. feminism for much of the 1900s. This caused Stone's many contributions to be overlooked in many histories of women's causes.

On August 13, 1968, the 150th anniversary of her birth, the United States Postal Service honored Stone with a 50¢ postage stamp. The image came from a photograph in Alice Stone Blackwell's biography of Stone.

In 1986, Stone was added to the National Women's Hall of Fame.

In 1999, six tall marble panels with bronze busts were added to the Massachusetts State House. One of the busts is of Lucy Stone. Two quotes from her are etched on her marble panel.

In 2000, Amy Ray of the Indigo Girls included a song called Lucystoners on her first solo album.

A building at Rutgers University in New Jersey is named for Lucy Stone. Warren, Massachusetts has a Lucy Stone Park. Anne Whitney's 1893 bust of Lucy Stone is on display in Boston's Faneuil Hall.

She is featured on the Boston Women's Heritage Trail.

On September 19, 2018, the U.S. Secretary of the Navy announced that a new ship would be named USNS Lucy Stone (T-AO 209). This ship is part of the John Lewis-class of supply ships named after U.S. civil and human rights heroes.

Lucy Stone's Home

Stone's birthplace, the Lucy Stone Home Site, is owned by The Trustees of Reservations. This group works to protect natural and historic places in Massachusetts. The site includes 61 acres of forested land in West Brookfield, Massachusetts. The farmhouse where Stone was born and married burned down in 1950. But its ruins are still there. Family members lived in the house until 1936. In 1915, suffragists placed a memorial tablet on the house. It read: "This house was the birthplace of Lucy Stone, pioneer advocate of equal rights for women." This tablet, though damaged by the fire, is now in a museum. After the fire, the farmland became forest. The Trustees acquired the home site in 2002 and have maintained it since.

See also

In Spanish: Lucy Stone para niños

In Spanish: Lucy Stone para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |