Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society facts for kids

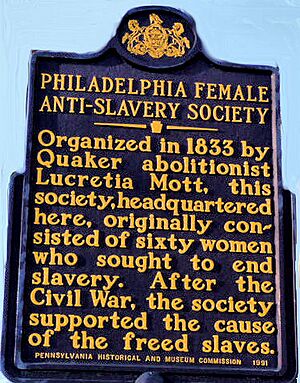

The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS) was a group started by women in December 1833. They wanted to end slavery in the United States. This group was formed just a few days after a larger male anti-slavery group, the American Anti-Slavery Society, also began in Philadelphia.

The PFASS stopped its work in March 1870. This was after the 14th and 15th Amendments were added to the U.S. Constitution. These amendments helped give rights to formerly enslaved people.

Eighteen women started the PFASS. Some important founders included Lucretia Mott, Mary Ann M'Clintock, and members of the Forten family: Margaretta Forten, her mother Charlotte, and her sisters Sarah and Harriet.

The PFASS was connected to the American Anti-Slavery Society, which was started by William Lloyd Garrison and other men. Women could not join the male group, so they created their own. This group was mostly white but also included Black women. It shows how important women were behind the scenes in the fight against slavery. It also highlights how gender and race affected society at that time, especially with the idea that women should only focus on home life.

Who Joined the PFASS?

Historians often say the PFASS was one of the few anti-slavery groups that included both Black and white members before the Civil War. This was very rare, even among other women's anti-slavery groups. Most members came from middle-class families.

Lucretia Mott is one of the most famous white women linked to the PFASS. Other important white members were Sarah Pugh and Mary Grew. Sarah Pugh was the president, and Mary Grew was the secretary for most of the group's history. Angelina Grimké, another well-known woman who fought against slavery, also joined. Many white female members were Quakers, a religious group.

Free Black women also helped start the society. Important Black members included Grace Bustill Douglass, Sarah Mapps Douglass, Hetty Reckless, and Charlotte Forten with her daughters Harriet, Sarah, and Margaretta. These women were part of Philadelphia's leading African American families.

Seven of the eighteen women who signed the PFASS constitution were Black. Records show that ten Black women regularly attended meetings. Many Black women also held leadership roles in the society.

Sarah Forten helped found the group and served on its board for three years. Margaretta Forten also helped start the society. She often worked as the recording secretary or treasurer. She also helped write the group's rules and was on its education committee. Margaretta Forten even proposed the group's last statement, celebrating the success of the anti-slavery cause after the Civil War amendments. By holding these important positions, the Forten women helped the mostly white group also share the strong views of Black abolitionists.

Black middle-class women in Philadelphia first formed groups to help women learn to read and write. These groups helped them educate themselves and their children. They also helped them gain skills for community work. Many members of these reading groups later joined the PFASS. These groups were a key part of the fight against slavery.

It was very unusual to see such a mix of Black and white women working together in a society, even in a free city like Philadelphia. Black members helped write the group's rules and decide its main goals.

What the PFASS Did

In the 1830s, the PFASS mainly focused on:

- Collecting signatures for anti-slavery petitions.

- Holding public meetings.

- Organizing events to raise money.

- Helping free Black people in the community.

Between 1834 and 1850, the PFASS sent many petitions to the Pennsylvania state government and to Congress. They asked the Pennsylvania legislature to allow jury trials for people suspected of being runaway slaves. They also asked Congress to end slavery in Washington, D.C., and stop the trade of enslaved people between states. Black women leaders in the PFASS helped organize these efforts.

At a time when women could not vote, petitions were one of the few ways they could express their political views. Petition campaigns brought women out of their homes and into their neighborhoods. They went door-to-door, talking to people and spreading their message. This not only challenged what society expected of women but also changed the anti-slavery movement from a moral issue to a political one. These petitions eventually led the U.S. House of Representatives to pass the gag rule, which stopped them from discussing anti-slavery petitions.

When Congress refused to listen to their petitions, and because they feared violence, the PFASS changed its plans in the 1840s. They spent less time on petitions and more on fundraising. Their main fundraising event was an annual fair. They sold handmade items, like needlework with anti-slavery messages, and anti-slavery books. For example, the famous book The Anti-Slavery Alphabet was printed and sold at the 1846 Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Fair.

PFASS meetings involved planning for the fair and organizing sewing groups. By the 1850s, the fairs became big events. Besides selling items, the fairs featured speeches by famous abolitionists. These speeches attracted large crowds who paid to get in.

The group's successful fundraising helped them gain power in the state anti-slavery society. The PFASS provided a large part of all the money donated to the state society. From 1844 to 1849, the money raised by the Philadelphia women covered about 20% of the state anti-slavery society's budget. It made up 31% to 45% of all donations. This allowed women to stay visible and have a strong voice in the statewide movement to end slavery.

The PFASS also helped the free Black community financially. Led mainly by its Black female members, the PFASS supported Sarah Douglass's school for free Black girls. The society continued to give money to the school every year throughout the 1840s. The leadership and support from the Forten women helped ensure these regular contributions. This shows that Black women played a very important leadership role within the PFASS.

The PFASS also raised money for clothes, shelter, and food to help runaway enslaved people. Black women members, led by Hetty Reckless, worked closely with the Vigilance Association of Philadelphia. This was a group of men who helped runaway enslaved people. Reckless convinced PFASS members to give money to community projects. They provided runaway enslaved people with places to stay, food, clothes, medical help, jobs, money, and advice about their legal rights.

However, white female members of the society were divided on whether helping runaway enslaved people was truly anti-slavery work. Lucretia Mott believed this was not the PFASS's role. This difference showed how the goals of Black and white abolitionists sometimes differed. Black women saw helping runaway enslaved people as a practical way to fight slavery. White women, on the other hand, often saw these actions as "distractions" from the main goal of ending slavery.

How Women's Rights Began

As women played a key role in the anti-slavery movement, both white and Black members of the PFASS supported the new idea of giving women the right to vote. They also supported women taking on roles usually done by men, like speaking in public.

Historians have noted that the women of the PFASS were very important in the start of American feminism, which is the movement for women's rights. They played a key role in the women's movement that began at the Seneca Falls Convention. More recent studies also highlight the important role of free Black women in these groups. Black female community leaders, like those in the PFASS, helped shape Black women's community work for future generations, especially in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |