Harriet Forten Purvis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Harriet Forten Purvis

|

|

|---|---|

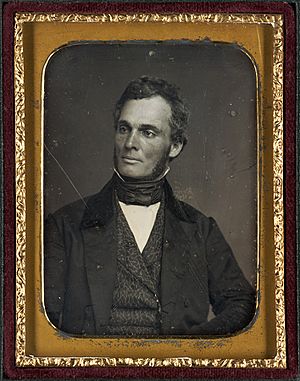

Purvis c. 1874

|

|

| Born |

Harriet Davy Forten

1810 |

| Died | June 11, 1875 (aged 64–65) Washington, D.C., US

|

| Other names | Hattie Purvis Jr. |

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) | Robert Purvis |

| Children | 8, including Harriet Jr. and Charles |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

Harriet Forten Purvis (1810–June 11, 1875) was an important African-American activist. She fought to end slavery and for women's right to vote. With her mother and sisters, she helped start the first group of women, both Black and white, who worked to end slavery. This group was called the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Harriet also used her home as a safe place for people escaping slavery, as part of the Underground Railroad. She and her husband, Robert Purvis, also started a school called the Gilbert Lyceum. After the Civil War, she continued to fight against unfair separation (segregation) and for Black people's right to vote.

Contents

Harriet's Early Life and Family

Growing Up in Philadelphia

Harriet Davy Forten was born in Philadelphia in 1810. She was one of eight children of James Forten and Charlotte Vandine Forten. Her father, James Forten, was a rich inventor, businessman, and abolitionist. An abolitionist is someone who wants to end slavery. He was born free.

James Forten was a powder boy during the American Revolutionary War and was captured. He later got his start in business from a white sailmaker named Robert Bridges. Harriet was named after one of Bridges' daughters.

The Forten family was very well-known in Philadelphia. They were respected for their kindness and hospitality. A famous writer, William Lloyd Garrison, said the family had "few superiors in refinement, in moral worth." In 2002, Professor Molefi Kete Asante named James Forten one of the 100 Greatest African Americans.

A Family of Activists

Harriet's parents, James and Charlotte, helped create and fund six groups that worked to end slavery. Many abolitionists who visited Philadelphia stayed at the Forten home.

The first group in the country that included both Black and white women working against slavery was the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Harriet's mother, her daughters, and Lucretia Mott founded this group. The Forten women were very active members and leaders in it.

Harriet's father also started a private school with Grace Douglass. Harriet and her brothers and sisters went to this school. They also had private teachers who taught them foreign languages and music. Her younger sisters were Sara and Margaretta. The girls were raised to be polite and educated women. The poet John Greenleaf Whittier even wrote a poem for Harriet, showing his admiration for her.

Harriet's Interests and Hobbies

Harriet loved to read many different kinds of books. These included novels, religious books, and writings about ending slavery. She also enjoyed reading William Shakespeare. She liked to debate and had a clear speaking voice when reading aloud. She looked for friends who shared her love for music, art, and literature. Harriet was a member of several literary groups, like the Black Female Literary Association.

Marriage and Family Life

Harriet and Robert Purvis

Harriet married Robert Purvis on September 13, 1831, at her family's home. Robert was a wealthy man from South Carolina, with Moroccan and English heritage. Their wedding was an "elegant ceremony" led by an Episcopal bishop. Some people talked about their different skin tones, but Robert was always open about his family background.

Harriet and Robert were both abolitionists and worked together on their shared goals. Their marriage was special because they were equal partners. This was rare during their time. It showed how much Robert believed in equality and how Harriet could be active in both her home life and public work.

They had servants, including an English governess. This allowed Harriet to spend time working on the causes she cared about. Their beautiful English-style home was a peaceful place for visitors. Harriet often welcomed fellow activists and abolitionists, like William Lloyd Garrison, into her home. They had strong friendships with both Black and white reformers. They believed that everyone was "but one race."

However, not everyone in Philadelphia agreed with their views. In the 1830s, there were riots and violence against Black people and those who helped runaway slaves. In 1834, many churches and buildings owned by Black people were burned down.

Harriet's sister, Sarah, married Robert's brother, Joseph Purvis. Sarah wrote articles and poems for a newspaper called The Liberator. A Black band leader, Frank Johnson, wrote music for her poem The Grave of the Slave. This song was often played at anti-slavery events.

Around 1840, Harriet's brother Robert became a widower. His daughter, Charlotte Forten Grimké, came to live with the Purvis family. She was taught by a private tutor. Because of segregation in Philadelphia, Robert felt she would not get a good education in the city. Charlotte found comfort and joy living with her aunt Harriet. Later, in 1853, Charlotte moved to Salem, Massachusetts, to live with another important Black family.

Harriet and Robert had eight children. One of their sons, Charles Burleigh Purvis, became a doctor and a medical school teacher. He was the first African American to run a civilian hospital. During the American Civil War, he worked as a doctor and nurse for the Union Army.

Harriet's Activism

Fighting for Freedom and Rights

Early in her marriage, Harriet had her first child while Robert traveled and spoke against slavery. Harriet was a member of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Even when she was pregnant, she went to the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in New York in 1837 with two of her sisters.

In 1838, the convention was held in Philadelphia at the new Pennsylvania Hall. This hall was built by the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. Robert Purvis helped Harriet out of their carriage. Angry people watching thought they were an interracial couple promoting mixing of the races. The hall was later set on fire by people who supported slavery. After this, the convention met at a school run by teacher and abolitionist Sarah Pugh. Both Black and white women worked as equals in this group, which was very unusual at the time. This caused strong reactions from people who feared racial mixing and from those who thought women should not be involved in public matters.

Harriet was not scared by the riot. She attended the convention the next two years. She was a delegate in 1838 and 1839. In 1839, they could not rent a hall in Philadelphia, so the convention met in a riding stable.

Harriet also helped organize fairs for the Philadelphia Women's Anti-Slavery Society. Between 1840 and 1861, these fairs raised a lot of money to support their cause. In 1841, the group protested against Black Sunday schools being excluded from an annual exhibition. The next year, it became an event for both Black and white children.

After the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (which ended slavery) was passed, Harriet continued to work for the rights of African Americans. The Female Antislavery Society kept meeting. In September 1866, they discussed the situation in the South. Robert and Harriet also joined the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League and the American Equal Rights Association. Harriet spoke out for the right to vote for both women and Black people. She also fought against segregation.

Harriet, Robert, and Octavius Catto worked to end segregation on streetcars in Philadelphia. In 1867, a state law was passed that gave equal access to public transportation for all races.

The Free Produce Movement

Harriet also joined the Free Produce Society. Members of this group bought only local produce and refused to buy goods grown or picked by enslaved people. Harriet often attended Free Produce Conventions and was a member of the Colored Free Produce Association. She only bought products that were not made or grown by slaves. She continued this practice even when some people questioned if it was truly effective. Harriet, Lucretia Mott, and Sarah Pugh stuck to their beliefs about free produce. They felt that not following their principles would hurt their cause.

Helping on the Underground Railroad

Harriet and Robert ran a station of the Underground Railroad in their home in Philadelphia. The Underground Railroad was a secret network of safe houses and routes that helped enslaved people escape to freedom. Robert was even called the father of the Underground Railroad because he founded Philadelphia's Vigilance Committee.

Life became dangerous in central Philadelphia, so the family moved to a farm in rural Byberry, Philadelphia in 1843 or 1844. They helped about 9,000 runaway slaves on their journey to Canada. Slaves were hidden from authorities in their Byberry house through a secret trap door that Robert installed in the floor. Harriet hosted meetings of abolitionists in her house. She was also a leader of the Female Vigilant Society, which gave money for travel and clothes to those escaping slavery.

Fighting for Better Education

As a mother, Harriet saw even more clearly the need for laws against slavery and for greater equality for African Americans. Private schools for Black children were not as good as the public schools for white children. Her children would face racial prejudice, even though their family had a comfortable life.

The Byberry Friends Meeting, a Quaker meeting house, was across the street from the Purvis home. The Purvis children attended the Byberry Friend School. Nearby were also the Friends' Library Company and Purvis Hall. Robert Purvis built Purvis Hall in 1846. It was a meeting place for anti-slavery gatherings and other community events.

In 1853, Robert Purvis refused to pay the local school tax because his children were not allowed to get a good education in the public schools. Their children were taught by private tutors and at Quaker schools. Harriet and her husband also founded the Gilbert Lyceum, a place for public lectures and learning.

Working for Women's Right to Vote

Harriet was a member of the National Woman Suffrage Association. She was friends with Susan B. Anthony and Lucretia Mott. These women also worked for the right to vote for Black people and women, against slavery, and for the safe passage of runaway slaves.

Harriet and her sister Margaretta Forten were important organizers of the Fifth National Women's Rights Convention in Philadelphia in 1854. Harriet's daughter, Hattie, later became the first African American vice president of the National Woman Suffrage Association. Harriet's sisters and her niece Charlotte were also early supporters of women's right to vote. Other Black women who worked for women's voting rights included Sojourner Truth, Amelia Shadd, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, Nancy Prince, and Francis Ellen Watkins Harper.

Later Years

In 1873, Robert and Harriet moved to a neighborhood called Mount Vernon with their daughters Georgianna and Harriet, who were still at home. They kept their Byberry home, Harmony Hall, and rented it out.

The family faced a lot of illness. Three of their sons died, one from meningitis and the others from tuberculosis. Tuberculosis was also the cause of Harriet's death on June 11, 1875. She died in Washington, D.C., where Robert was working. She was buried in Germantown at the Quaker Fair Hill Burial Ground.

Two years after Harriet's death, another daughter died. Robert later moved to a house in Mount Vernon, Philadelphia. Around 1878, he married a Quaker poet named Tacie Townsend.

In Other Media

- Letters to Aunt Hattie, a play written and performed by Gilletta "Gigi" McGraw

- Performances:

- February 2, 2020, Brandywine River Museum of Art.

- February 22, 2020, hosted by the Burlington County, NJ, Women's Advisory Council.

- Performances:

- Character in Sarah’s Poem, a play written by Charissa Menefee. Harriet Forten Purvis was played by Ray-Nita Powell in March 2018.

See also

In Spanish: Harriet Forten Purvis para niños

In Spanish: Harriet Forten Purvis para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |