Free-produce movement facts for kids

The free-produce movement was a worldwide boycott of goods made by people forced into slavery. It was a way for people who wanted to end slavery (called abolitionists) to fight it without violence. Even people who couldn't vote could take part.

In this movement, "free" meant "not enslaved," like having the rights of a citizen. It didn't mean "without cost." Also, "produce" didn't just mean fruits and vegetables. It included many things made by enslaved people, such as clothes, shoes, soap, and candy.

Contents

Early Days of Free Produce

The idea for this movement started with the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in the late 1700s. Quakers believed everyone was equal and didn't believe in violence. By 1790, they had stopped owning enslaved people themselves.

Some Quakers, like Anthony Benezet and John Woolman, felt that buying goods made by enslaved people helped keep slavery going. They argued that people should stop buying these goods for moral and economic reasons. This idea was popular because it offered a peaceful way to fight slavery.

Spreading the Boycott Idea

In the 1780s, the movement grew beyond just Quakers. In Britain, abolitionists (many of them Quakers or formerly enslaved people) formed a group in 1787 to end the slave trade. In 1789, a law to end the slave trade was proposed in parliament, but it was slow to pass.

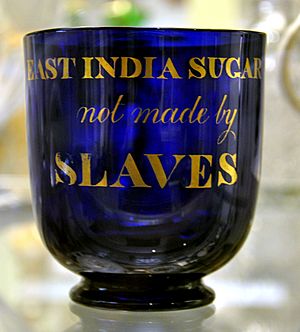

This led to frustration, and people started boycotting goods. William Fox wrote a popular leaflet that urged people to boycott sugar made by enslaved people. Over 250,000 copies were printed!

The leaflet said that if you bought slave-made goods, you were part of the problem. It said, "In every pound of sugar used we may be considered as consuming two ounces of human flesh." People often described slave-made products as being "stained" with the blood, tears, and sweat of enslaved people.

Both shoppers and store owners joined the boycotts. In 1791, a British merchant named James Wright announced he would no longer sell sugar unless it was made without slavery. Women, who couldn't vote, were very important in promoting and joining the sugar boycott. At its peak, over 400,000 people in Britain took part. However, the movement lost support when the French Revolution became violent in 1792.

The Movement in the 1800s

In 1811, Elias Hicks wrote a book that argued for a consumer boycott of slave-made goods. He believed it would stop slaveholders from getting rich and living in luxury from their cruel practices.

His book helped the free-produce movement argue for stopping all goods made by enslaved labor, like cotton cloth and cane sugar. Instead, people should buy products made by paid, free workers. Most of the first free-produce stores were started by Quakers, like Benjamin Lundy's store in Baltimore in 1826.

Growth Across America

In 1826, the American abolitionist boycott really started. Quakers in Wilmington, Delaware, created a formal free-produce group. That same year, Lundy opened his store in Baltimore, Maryland, selling only goods made by free people.

The movement grew even more in 1827 with the "Free Produce Society" in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This group wanted to show the hidden costs of goods like cotton, tobacco, and sugar that came from enslaved labor. Quaker women, including Lucretia Coffin Mott, joined the Society and spoke at meetings. Lydia Child, a famous abolitionist writer, also ran a "free" dry goods store in Philadelphia in 1831.

African Americans Join In

In 1830, African-American men formed the "Colored Free Produce Society of Pennsylvania." The next year, African-American women formed their own society. Some Black businesses started selling only free produce. For example, William Whipper opened a free grocery store in Philadelphia. A Black candy maker in the same city used only sugar from free labor and even made the wedding cake for abolitionist Angelina Grimké.

In New York, a newspaper called Freedom's Journal explained that if 25 Black people bought sugar from slaveholders, it would take one enslaved person to produce that sugar.

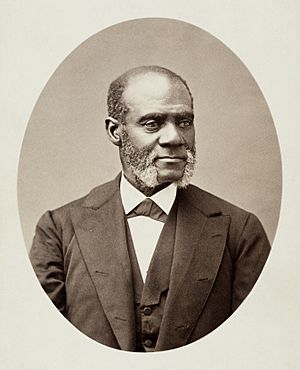

African Americans passed resolutions supporting free produce at their conventions in the 1830s. Henry Highland Garnet spoke about how free produce could strike a blow against slavery. Black abolitionist Frances Ellen Watkins always talked about the movement in her speeches. She said she would pay more for a "Free Labor" dress, even if it wasn't as fancy. She called the movement "a sign of hope" and a way to show how serious people were about their beliefs.

American Free Produce Association

In 1838, a Free Produce store opened in the new Pennsylvania Hall (Philadelphia). Supporters from different states met there to form the American Free Produce Association. This group looked for alternatives to slave-made products and created ways to distribute them. The Association published many pamphlets and a journal called Non-Slaveholder from 1846 to 1854.

British Groups Support Free Produce

The British India Society, founded in 1839, also supported free produce. In the 1840s and 1850s, British groups similar to the American Free Produce Association were formed. These were led by Anna Richardson, a Quaker abolitionist in Newcastle. The Newcastle Ladies' Free Produce Association started in 1846, and by 1850, there were at least 26 such groups.

Businesses Using Free Labor

Quaker George W. Taylor started a textile factory that used only cotton grown without enslaved labor. He worked to make high-quality cotton goods available. Abolitionist Henry Browne Blackwell invested money in businesses trying to make cheaper sugar using machines and free labor. However, these efforts were not successful.

Why the Movement Didn't Fully Succeed

The free-produce movement didn't become a huge success, and many places stopped supporting it after a few years.

- Higher Cost: Goods made without enslaved labor were often more expensive.

- Hard to Find: It was sometimes difficult to find these special products.

- Quality Issues: Sometimes, the non-slave goods were not as good quality. One store owner said he often received sugar that tasted bad and rice that was "very poor, dark and dirty."

- Uncertain Origin: It was hard to be sure where some goods truly came from.

- Small Impact: The benefits to enslaved people or the reduction in demand for slave-made goods were very small.

Many abolitionists didn't focus on this issue. Even William Lloyd Garrison, a key abolitionist leader, first supported the movement but later said it was impossible to enforce and a distraction. The national association ended in 1847, but Quakers in Philadelphia continued their efforts until 1856.

Images for kids

-

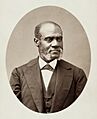

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper supported the free-produce movement, regularly saying she would pay more for a "Free Labor" dress

-

In 1850, Henry Highland Garnet toured Great Britain to urge Britons to support free produce.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |