Henry Highland Garnet facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry H. Garnet

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | December 23, 1815 New Market, Maryland, U.S.

|

| Died | February 13, 1882 (aged 66) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Oneida Institute |

| Occupation | Minister (Christianity), Abolitionist |

| Spouse(s) | Julia Williams |

| Religion | Presbyterian |

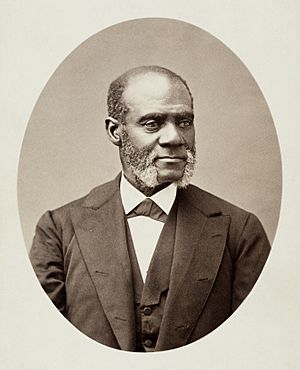

Henry Highland Garnet (December 23, 1815 – February 13, 1882) was an important African-American leader. He was an abolitionist, which means he worked to end slavery. He was also a minister, teacher, and a great public speaker.

Garnet escaped slavery in Maryland with his family when he was a child. He grew up in New York City and went to school there. He became a strong supporter of ending slavery, believing that religion could help this cause.

He was known for encouraging Black Americans to take action for their own freedom. For a while, he thought Black Americans should move to places like Mexico, Liberia, or the West Indies. But the American Civil War changed his mind.

In 1841, he married Julia Williams, who was also an abolitionist. They had a family. A young woman named Stella Weems, who had escaped slavery, lived with them. Stella would share her story when Garnet preached against slavery.

In 1852, Garnet and his family moved to Kingston, Jamaica, where he worked as a missionary. Sadly, Stella died there from yellow fever. The Garnet family also got sick but returned to America.

On February 12, 1865, Garnet made history. He gave a sermon in the U.S. House of Representatives. He was the first Black man to speak in the U.S. Capitol. This happened shortly after Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment, which officially ended slavery.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Henry Garnet was born into slavery in Chesterville, Maryland, on December 23, 1815. His grandfather was an African chief who was captured and sold into slavery. In 1824, when Henry was about nine years old, his family of 11 escaped. They used a covered wagon and got help from Quakers and the Underground Railroad in Delaware.

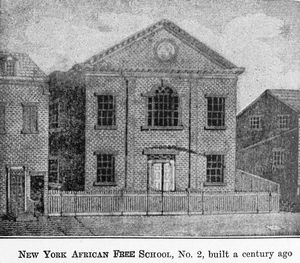

When Henry was ten, his family settled in New York City. From 1826 to 1831, he went to the African Free School. This school helped educate many Black children. His studies were sometimes interrupted because he had to work. He worked on ships traveling to Cuba and Virginia.

In 1829, slave hunters tried to capture his family again. His sister was arrested but proved she lived in New York, a free state. His father jumped from a two-story building to escape. Henry himself bravely faced the slave hunters with a knife. His friends helped him escape to Long Island, where a Quaker protected him. He then worked as an indentured servant but left after injuring his leg. He returned to the African Free School for another year.

While at school, Garnet started working against slavery. His classmates included other future leaders like Charles L. Reason and George T. Downing. In 1831, he continued his studies at the Phoenix High School for Colored Youth. There, he also attended Sunday school and became a Christian.

In 1834, Garnet and his friends started a club called the Garrison Literary and Benevolent Association. It was named after the famous abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. This club supported the anti-slavery movement.

In 1835, Garnet enrolled at the Noyes Academy in New Hampshire. However, people who were against abolitionism destroyed the school. They forced the Black students to leave town. Garnet then finished his education at the Oneida Institute in New York. This school was special because it accepted students of all races. He was known for being smart and a great speaker. After graduating in 1839, he injured his knee, which later had to be amputated.

Family Life

In 1841, Henry Garnet married Julia Williams. They had met at the Noyes Academy and she also studied at the Oneida Institute. They had three children, but only one lived to adulthood.

Becoming a Minister and Activist

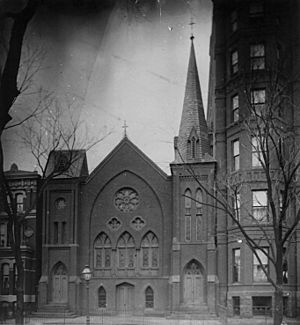

In 1839, Garnet moved to Troy, New York. He taught school and studied to become a minister. In 1842, he became the pastor of the Liberty Street Presbyterian Church, where he served for six years. He also published an anti-slavery newspaper called National Watchman. Garnet believed in the temperance movement, which worked against alcohol use. He also strongly supported using politics to end slavery.

Garnet used his church to help fugitive slaves hide. A wealthy supporter named Gerrit Smith even announced a plan in Garnet's church to give land to Black men who couldn't vote.

Later, Garnet moved back to New York City. He joined the American Anti-Slavery Society and often spoke at anti-slavery meetings. One of his most famous speeches was "Call to Rebellion" in 1843. In this speech, he urged enslaved people to fight for their own freedom, even with armed rebellion. Other abolitionists, like Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, thought his ideas were too extreme. They worried it would make white people more afraid and resistant to the cause.

In 1848, Garnet moved to Peterboro, New York, where Gerrit Smith lived. Garnet supported Smith's Liberty Party, a political group that worked for reforms and later joined the Republican Party.

His Role in the Anti-Slavery Movement

The role of women in the abolitionist movement caused a split in the American Anti-Slavery Society. Garnet and other Black ministers formed a new group called the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. This group focused on using political action to end slavery and believed men should lead the organization.

By 1849, Garnet began to think that Black people should move to other countries like Mexico, Liberia, or Haiti. He believed they would have more opportunities there. To support this idea, he started the African Civilization Society. This group aimed to create a Black colony in West Africa. Garnet also supported the idea of Black nationalism in the United States, which included creating Black communities in the Western territories.

In 1850, Garnet traveled to Great Britain. He was invited by Anna Richardson, who supported the free produce movement. This movement encouraged people to avoid buying products made by enslaved labor. Garnet was a popular speaker and lectured in Britain for two and a half years. While he was there, his seven-year-old son, James, died. Later, his wife Julia, their young son Henry, and their adopted daughter Stella joined him in Great Britain.

In 1852, Garnet became a missionary in Kingston, Jamaica. He and his family lived there for three years. His wife, Julia, ran a school for girls. Garnet faced health problems, which led the family to return to the United States.

After John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, Garnet openly supported John Brown's actions. He said that anyone who loved freedom should agree that the raid was right.

In 1859, Garnet was president of the African Civilization Society. Its goal was to help Christianize and civilize Africa. When the American Civil War began, Garnet stopped hoping for emigration. He focused on helping Black people in America. During the New York City draft riots in 1863, mobs attacked Black people and their homes. Garnet and his family escaped by quickly removing their nameplate from their door. He helped organize support for sick soldiers and victims of the riots.

When the government allowed Black soldiers to join the army, Garnet helped recruit them. He moved to Washington, D.C., to support the Black soldiers and the war effort. He preached to many of them as the pastor of the Liberty (Fifteenth) Street Presbyterian Church from 1864 to 1866. During this time, he gave his historic speech to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1865, celebrating the end of slavery.

Later Life and Legacy

After the Civil War, in 1868, Garnet became president of Avery College in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Later, he returned to New York City and became a pastor at the Shiloh Presbyterian Church.

He continued to be active in politics. He supported the Cuban independence movement. In 1878, he hosted Cuban revolutionary leader Antonio Maceo at his home in New York City.

His first wife, Julia Williams, passed away in 1870. In 1875, Garnet married Sarah Smith Tompkins. She was a teacher, school principal, and community organizer in New York.

Ambassador to Liberia

Garnet's last wish was to visit Liberia, where his daughter Mary lived, and to die there. He was appointed as the U.S. Minister (ambassador) to Liberia. He arrived there on December 28, 1881, but sadly died of malaria on February 13, 1882.

The Liberian government gave him a state funeral. As described by Alexander Crummell:

They buried him like a prince, this princely man, with the blood of a long line of chieftains in his veins, in the soil of his fathers. The entire military forces of the capital of the republic turned out to render a last tribute of respect and honor. The President and his cabinet, the ministry of every name, the president, professors and students of the college, large bodies of citizens from the river settlement, as well as the townsmen, attended his obsequies as mourners. A noble tribute was accorded him by Rev. E. W. Blyden, D. D., LL. D., one of the finest scholars and thinkers in the nation. Minute guns were fired at every footfall of the solemn procession.

He was buried at Palm Grove Cemetery in Monrovia.

Even though Frederick Douglass and Garnet had disagreed for many years, Douglass still honored Garnet's life and achievements after his death.

Honors and Recognition

- In 1952, Garnet's picture was included in a mural called Civil Rights Bill Passes, 1866 in the U.S. Capitol building.

- Two schools are named after him: P.S. 175, the Henry Highland Garnet School for Success in Harlem, and the Henry Highland Garnet Elementary School in Chestertown, Maryland.

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Henry Highland Garnet on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

- The Garnet School in Washington, D.C., was named in his honor in 1880. It later became part of Shaw Middle School.

- Garnet High School in Charleston, West Virginia, was named for him from 1900 until 1956. Today, the building is the Garnet Career Center.

- Garnet is remembered on a New Hampshire historical marker (number 246) at Noyes Academy in Canaan.

See also

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |