Ten Years' War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ten Years' War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

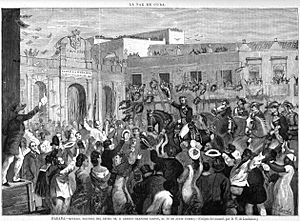

Embarkation of the Catalan Volunteers from the Port of Barcelona by Ramón Padró y Pedret |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

50,000–100,000 dead

|

81,248–90,000 dead

|

||||||

The Ten Years' War (known in Spanish as Guerra de los Diez Años; 1868–1878) was a major conflict in Cuba. It was also called the Great War or the War of '68. This war was a big part of Cuba's fight to become independent from Spain.

The uprising was started by wealthy Cuban landowners and other local people. On October 10, 1868, a sugar mill owner named Carlos Manuel de Céspedes and his supporters declared Cuba's independence. This event kicked off the war. It was the first of three wars Cuba fought against Spain to gain freedom. The others were the Little War (1879–1880) and the Cuban War of Independence (1895–1898). The last war eventually involved the United States, leading to the Spanish–American War.

Why the War Started

Slavery in Cuba

Cuban business owners wanted big changes from Spain, which ruled the island. Spain had been slow to stop the slave trade. This led to many more enslaved Africans being brought to Cuba. About 90,000 slaves arrived between 1856 and 1860.

This happened even though many people in Cuba wanted to end slavery. Also, keeping slaves was becoming very expensive for plantation owners in the east. New farming tools and methods meant fewer slaves were needed.

After an economic crisis in 1857, many businesses, including sugar plantations, failed. The movement to end slavery grew stronger. They wanted to free slaves slowly, with Spain paying money to slave owners. Some plantation owners also preferred to hire Chinese immigrants as workers, looking ahead to a time without slavery. Over 125,000 Chinese workers came to Cuba before the 1870s.

In 1865, important Cubans asked the Spanish government for four things:

- Fairer taxes on goods.

- Cubans to have a say in the Spanish government.

- Equal legal rights for Cubans and Spaniards.

- A complete stop to the slave trade.

Spain's Rules for Cuba

At this time, the Spanish government was changing. Powerful, old-fashioned politicians gained control. They wanted to stop any new, modern ideas. They made military courts more powerful. The government also added a six percent tax increase on Cuban businesses and farms.

Also, people were not allowed to speak out against the government. Newspapers were silenced. This made many Cubans very unhappy, especially the rich landowners in Eastern Cuba.

The attempts to make reforms failed. An "Information Board" that discussed changes was shut down. Another economic crisis in 1866-1867 made things worse. The Spanish government kept making huge profits from Cuba. But they did not spend this money to help the island's people.

Instead, the money went to military costs (44%), government expenses (41%), and even to another Spanish colony (12%). Spaniards made up only 8% of Cuba's population. Yet, they controlled over 90% of the island's wealth. Cubans born on the island had no political rights. They had no one to represent them in the Spanish government. These unfair conditions led to the first serious push for independence, especially in Eastern Cuba.

Planning the Revolution

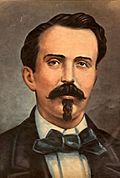

In July 1867, a group called the "Revolutionary Committee of Bayamo" was formed. It was led by Francisco Vicente Aguilera, a very rich plantation owner. The plan for rebellion quickly spread to other towns in the Oriente province. Carlos Manuel de Céspedes became a key leader of the uprising in 1868.

Céspedes was from Bayamo and owned a sugar mill called La Demajagua. The Spanish knew he was against their rule. They tried to make him give up by putting his son Oscar in prison. But Céspedes refused to give in, and Oscar was sadly executed.

Key Events of the War

The Uprising Begins

Céspedes and his followers had planned to start their uprising on October 14. But they had to begin four days earlier because the Spanish found out about their plan. In the early morning of October 10, Céspedes declared independence. This was called the "10th of October Manifesto" at his sugar mill, La Demajagua. This moment marked the start of the war against Spanish rule in Cuba.

Céspedes freed his enslaved people and asked them to join the fight. October 10 is now a national holiday in Cuba, known as Grito de Yara ("Cry of Yara").

At first, the uprising almost failed. Céspedes tried to take the nearby town of Yara on October 11. But his forces were defeated. Despite this, the uprising gained support in other parts of the Oriente province. The independence movement kept growing in eastern Cuba. By October 13, the rebels had taken eight towns that supported their cause and helped them get weapons. By the end of October, about 12,000 volunteers had joined the rebellion.

New Fighting Tactics

In the same month, Máximo Gómez taught the Cuban forces a very effective fighting method: the machete charge. Gómez was a former cavalry officer for the Spanish Army in the Dominican Republic. He taught the Cuban fighters to use both firearms and machetes together. This created a powerful double attack against the Spanish.

When Spanish soldiers formed a square (a common tactic then), they could be shot by hidden Cuban infantry. They were also vulnerable to pistol and carbine fire from charging cavalry. Like in the Haitian Revolution, many European soldiers died from yellow fever. This was because Spanish-born troops had no natural protection against this disease common in Cuba.

The 10th of October Manifesto

Carlos Manuel de Céspedes called on people of all races to fight for freedom. He raised the new flag of an independent Cuba. He rang the bell of his mill to celebrate his declaration. This manifesto was signed by him and 15 others. It listed how Spain had treated Cuba unfairly. Then, it explained what the movement wanted:

Our goal is to enjoy freedom, for which God created humans. We believe in kindness, understanding, and fairness for everyone. We see all people as equal. We will not exclude anyone from these benefits, not even Spaniards, if they choose to stay and live peacefully with us.

Our goal is for the people to help create laws and decide how money is collected and spent.

Our goal is to end slavery and pay those who deserve it. We want freedom to gather, freedom of the press, and honest government. We want to respect and practice the basic rights of people, which make a nation independent and great.

Our goal is to get rid of Spanish rule and create a free and independent nation….

When Cuba is free, it will have a fair government created wisely.

The War Grows

After three days of fighting, the rebels captured the important city of Bayamo. Filled with joy from this victory, the poet and musician Perucho Figueredo wrote Cuba's national anthem, "La Bayamesa”. The first government of the new Cuban Republic was set up in Bayamo, led by Céspedes. However, the Spanish took the city back after three months, on January 12. The fighting had burned Bayamo to the ground.

The war spread in Oriente province. On November 4, 1868, Camagüey joined the fight. In early February 1869, Las Villas followed. However, the uprising did not gain much support in the western provinces like Pinar del Río, Havana, and Matanzas. Resistance there was mostly secret.

A strong supporter of the rebellion was José Martí. At just 16 years old, he was arrested and sentenced to 16 years of hard labor. He was later sent away to Spain. Martí later became a famous writer and Cuba's most important national hero. He was the main planner of the 1895–1898 Cuban War of Independence.

After some wins and losses, Céspedes replaced Gómez as the head of the Cuban Army in 1868. He chose United States General Thomas Jordan, who had fought in the American Civil War. General Jordan brought a well-equipped force. His regular army tactics were effective at first. But they left the families of Cuban rebels too open to the harsh tactics of Blas Villate, also known as the Count of Valmaceda. Valeriano Weyler, who later became known as the "Butcher Weyler" in the 1895–1898 War, fought alongside the Count of Balmaceda.

After General Jordan left and went back to the US, Céspedes gave command back to Máximo Gómez. Slowly, a new group of skilled Cuban commanders grew up through the ranks. These included Antonio Maceo Grajales, José Maceo, Calixto García, Vicente Garcia González, and Federico Fernández Cavada. Fernández Cavada grew up in the United States and had an American mother. He had been a colonel in the Union Army during the American Civil War. His brother Adolfo Fernández Cavada also joined the Cuban fight for independence. On April 4, 1870, Federico Fernández Cavada was named Commander-in-Chief of all Cuban forces. Other important Cuban leaders fighting for the Mambí side included Donato Mármol, Luis Marcano-Alvarez, Carlos Roloff, Enrique Loret de Mola, Julio Sanguily, Domingo Goicuría, Guillermo Moncada, Quentin Bandera, Benjamín Ramirez, and Julio Grave de Peralta.

Creating a Government

On April 10, 1869, a meeting was held in Guáimaro (Camagüey) to create a government. This meeting aimed to give the revolution better organization and legal structure. Representatives from the areas that had joined the uprising attended. They discussed whether one leader should control both military and civilian matters. Or, if the civilian government should be separate and in charge of the military. Most people voted for the separation.

Céspedes was chosen as president of this meeting. General Ignacio Agramonte y Loynáz and Antonio Zambrana, who wrote most of the proposed Guáimaro Constitution, were chosen as secretaries. After finishing their work, the meeting became the House of Representatives, the highest power in the state. They elected Salvador Cisneros Betancourt as president, Miguel Gerónimo Gutiérrez as vice-president, and Agramonte and Zambrana as secretaries. On April 12, 1869, Céspedes was elected as the first president of the Republic in Arms. General Manuel de Quesada was chosen as Chief of the Armed Forces.

Spain's Harsh Actions

By early 1869, the Spanish government had not been able to make peace with the rebels. So, they started a war to wipe out the rebellion. The government passed several harsh laws:

- Rebel leaders and their helpers would be killed on the spot.

- Ships carrying weapons would be taken, and everyone on board would be killed immediately.

- Males aged 15 and older found away from their homes or farms without a good reason would be killed right away.

- All towns were told to raise a white flag (meaning surrender) or be burned to the ground.

- Any woman found away from her home or farm would be taken to camps in cities.

Besides its own army, the Spanish government used a group called the Voluntary Corps. This group was a militia formed earlier to fight against an announced invasion by Narciso López. The Corps became known for its cruel and bloody actions. Its members killed eight students from the University of Havana on November 27, 1871.

The Corps also captured the steamship Virginius in international waters on October 31, 1873. Starting on November 4, they killed 53 people, including the captain, most of the crew, and some Cuban rebels who were on board. These killings were only stopped when a British warship, led by Sir Lambton Lorraine, stepped in.

In an event called the "Creciente de Valmaseda", the Corps captured farmers (Guajiros) and the families of the Mambises (Cuban rebels). They either killed them right away or sent them in large groups to concentration camps on the island. The Mambises fought using guerrilla tactics. They were more successful in the eastern part of the island than in the west, where they lacked supplies.

Another Voluntary Corps was formed by Germans, called the "Club des Alemanes". Led by Fernando Heydrich, a group of German merchants and landowners created a troop to protect their properties in 1870. They were supposed to be neutral, as ordered by Otto von Bismarck. But they were seen as favoring the Spanish government.

Problems Among the Rebels

Ignacio Agramonte was killed by a stray bullet on May 11, 1873. Máximo Gómez replaced him as the commander of the central troops. Because of political disagreements and Agramonte's death, the Assembly removed Céspedes as president. They replaced him with Cisneros. Agramonte had realized that his dream government and constitution were not right for the Cuban Republic fighting a war. That is why he had left his secretary role and taken command of the Camaguey region. He then became a supporter of Céspedes.

Céspedes was later surprised and killed on February 27, 1874, by a fast-moving Spanish patrol. The new Cuban government had left him with only one guard. They also refused his request to leave Cuba for the US, where he wanted to help plan and send armed groups.

War Continues

The Ten Years' War was most intense in 1872 and 1873. But after Agramonte and Céspedes died, Cuban operations were mostly limited to the Camagüey and Oriente regions. Gómez tried to invade Western Cuba in 1875. However, most enslaved people and rich sugar producers in that area did not join the revolt. After his most trusted general, the American Henry Reeve, was killed in 1876, Gómez stopped his campaign.

Spain's efforts to fight were made harder by a civil war (Third Carlist War) that started in Spain in 1872. When that civil war ended in 1876, the Spanish government sent more troops to Cuba. Their numbers grew to over 250,000. These strong Spanish actions weakened the Cuban forces led by Cisneros. Neither side could win a clear victory or completely defeat the other. But in the long run, Spain gained the upper hand.

Rebellion Weakens

The deep disagreements among the rebels about how to organize their government and military became clearer after the Assembly of Guáimaro. This led to Céspedes and Quesada being removed in 1873. The Spanish took advantage of these regional differences. They also used fears that the enslaved people of Matanzas would upset the balance between white and black populations.

Spain changed its approach to the Mambises. They offered to forgive rebels and make reforms. The Mambises did not win for several reasons:

- They lacked organization and resources.

- Fewer white Cubans joined the fight.

- There was racism within the rebel groups, especially against Maceo and the goals of the Liberating Army.

- They could not bring the war to the western provinces, especially Havana.

- The US government was against Cuban independence. The US sold the latest weapons to Spain, but not to the Cuban rebels.

Peace Talks and Last Fighters

Tomás Estrada Palma became president of the Republic in Arms after Juan Bautista Spotorno. Estrada Palma was captured by Spanish troops on October 19, 1877. Because of many problems, the Cuban government's official bodies were dissolved on February 8, 1878. The remaining rebel leaders started talking about peace in Zanjón, Puerto Príncipe.

General Arsenio Martínez Campos, who was in charge of the new peace policy, arrived in Cuba. It took him almost two years to convince most rebels to accept the Pact of Zanjón. This agreement was signed on February 10, 1878, by a negotiating group. The document included most of the promises Spain had made.

The Ten Years' War ended, except for a small group in Oriente. This group was led by General Garcia and Antonio Maceo Grajales. They protested the peace agreement in Los Mangos de Baraguá on March 15.

After the War

The Pact of Zanjón

Under the agreement, a constitution and a temporary government were set up. But the strong spirit of the revolution was gone. The temporary government convinced Maceo to give up. With his surrender, the war ended on May 28, 1878. Many of the leaders who fought in the Ten Years' War became key figures in Cuba's War of Independence that began in 1895. These included the Maceo brothers, Maximo Gómez, and Calixto Garcia.

The Pact of Zanjón promised various changes to improve life for Cubans. The most important change was that all enslaved people who had fought for Spain were freed. The rebels had wanted to end slavery, and many people loyal to Spain also supported this. Finally, in 1880, the Spanish government officially ended slavery in Cuba and other colonies. This was done slowly. The law required freed slaves to keep working for their former owners for a few years. They were paid, but the wages were so low that they could barely support themselves.

Ongoing Problems

After the war ended, tensions between Cubans and the Spanish government continued for 17 years. This time was called "The Rewarding Truce." It included the start of the Little War (La Guerra Chiquita) between 1879 and 1880. People who wanted independence in that conflict became supporters of José Martí. He was one of the most passionate rebels who chose to live in exile rather than under Spanish rule.

Overall, about 200,000 people died in the Ten Years' War. Along with a serious economic downturn across the island, the war badly damaged the coffee industry. American taxes on Cuban goods also hurt Cuba's exports.

|

See also

In Spanish: Guerra de los Diez Años para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de los Diez Años para niños