Third Carlist War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Third Carlist War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Carlist Wars | |||||||

The Battle of Treviño, 7 July 1875, Francisco Oller |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

See list

|

See list

|

||||||

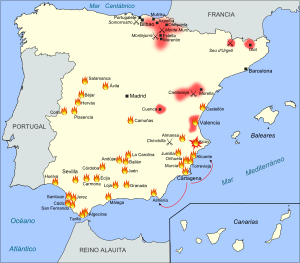

The Third Carlist War (1872–1876) was the last major conflict in a series of civil wars in Spain. These wars were fought between two main groups: the Carlists and the Liberals. The Carlists wanted a traditional king from the Bourbon family, Carlos VII. The Liberals supported Queen Isabella II and later her son, Alfonso XII, and wanted a more modern, liberal government. This war is sometimes called the "Second Carlist War" because an earlier, smaller conflict (1847–1849) was less important.

The war started after Queen Isabella II left the throne in 1868. A new king, Amadeo I, from Italy, became King of Spain in 1870. Many people did not like him. The Carlist leader, Carlos VII, promised to bring back old laws and customs to different Spanish regions. This included special laws called fueros in places like Catalonia, Valencia, Aragon, and the Basque region. These laws had been removed by King Philip V in the 1700s.

The Carlists' call for rebellion was strongest in Catalonia and the Basque region. They even set up a temporary government there. During the war, Carlist forces took over several towns, like La Seu d'Urgell and Estella. They also tried to capture big cities like Bilbao and San Sebastián, but they failed.

Spain saw many changes during the Third Carlist War. King Amadeo I left the throne in 1873, and the First Spanish Republic was declared. Then, in 1874, a military coup brought back the Bourbon monarchy with Alfonso XII as king.

After four years of fighting, Carlos VII was defeated on February 28, 1876. He went into exile in France. On the same day, King Alfonso XII entered Pamplona. After the war, the special Basque laws (fueros/foruak) were removed. Young men in these areas also had to join the Spanish army. The war caused between 7,000 and 50,000 deaths.

Contents

Why the War Started

The Third Carlist War began in 1872. It followed a revolution in 1868 that removed Queen Isabella II from power. Then, Amadeo I of Italy became King of Spain in 1870. The Carlists felt insulted because their leader, Carlos VII, was not chosen. The Carlists had strong support in northern Spain, especially in Catalonia, Navarre, and the Basque Provinces.

This war was the final part of a long struggle in Spain. It was a fight between those who wanted a modern, centralized government (Liberals) and those who wanted to keep old traditions (Carlists). This conflict started after the Peninsular War (1808–1814). Family disagreements within the royal family also made the conflict worse.

- The First Carlist War started because of a law that allowed women to inherit the throne.

- The Second Carlist War happened because no agreement could be found between the two sides.

- The Third Carlist War began when a foreign king was chosen for Spain.

Who Fought?

The Carlists

The Carlist movement began during the last years of King Ferdinand VII's rule (1784–1833). It was named after his brother, Carlos Maria Isidro. In 1830, Ferdinand VII changed a law so his daughter, Isabel, could become queen instead of his brother Carlos.

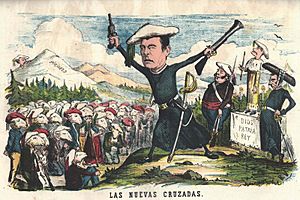

Carlos quickly became the symbol for Spain's conservative groups. Carlism was against liberal ideas. They strongly defended the Catholic Church and its traditions. Carlists also looked back to Spain's military past. Their motto was: "For God, for the Fatherland and the King."

Carlism was popular in the 19th century, especially among people who disliked the growing liberal ideas in Spain. Most Carlist supporters lived in rural areas. They were strong in places that had special laws before 1813, like Catalonia and the Basque Country. Catholic farmers and some nobles supported them.

The Liberals

After King Ferdinand VII died in 1833 without a male heir, the succession was debated. His daughter, Isabel, was too young to rule. So, her mother, Maria Cristina, became regent. Since conservatives supported Carlos, Maria Cristina had to side with the Liberals.

Liberals liked the ideas of the French revolution. Many high-ranking army officers and large landowners were Liberals. They also had some support from the middle classes.

Liberals wanted to modernize Spain. They supported new industries and social changes. Their reforms included selling church lands and building railways. They also had strong anti-church views.

Background to the War

Earlier Carlist Wars

The First Carlist War (1833-1840)

After Ferdinand VII died, Spain was divided into provinces. This change removed the special self-governing status of the Basque districts. This made the Basque people angry, and they rose up to support the Carlists. This led to the First Carlist War. Carlists took control of the countryside, but cities like Bilbao and San Sebastián stayed in Liberal hands. The fighting spread to other regions like Aragon and Catalonia.

The war ended in the Basque Country in 1839 with an agreement called the Convenio de Vergara. The Carlist leader, Carlos, went into exile. However, Carlists in Catalonia and Aragon continued fighting until 1840.

Important leaders emerged during this war. On the Liberal side, Baldomero Espartero became very powerful. For the Carlists, Ramón Cabrera became a key figure. His later decision to support the government during the Third Carlist War was very important.

The Second Carlist War (1846-1849)

The Second Carlist War began in 1846. It happened after a plan to marry Queen Isabel II to the Carlist claimant failed. Fighting was mainly in the mountains of southern Catalonia and Teruel. This war also came during a time of economic problems and unpopular taxes.

Many Carlist fighters from the first war had not surrendered. They formed small groups that attacked politicians and military units. By 1847, Carlists in Catalonia had gathered 4,000 men. In 1848, Carlists rose up in many parts of Spain. However, most of these uprisings failed except in Catalonia and Maestrat.

The war ended in 1849 when the Carlist leader was captured. Without a leader and facing a much larger Liberal army, Ramón Cabrera and the Carlists in Catalonia fled to France.

Spain's Political Situation Before the War

The Third Carlist War was the result of a long period of political problems in Spain. The rise of liberal ideas after Napoleon Bonaparte's occupation of Spain worried traditional groups. They decided to fight for their beliefs. The reigns of kings Ferdinand VII, Isabel II, and Amadeo I were full of political unrest.

Liberal reforms between 1833 and 1872 weakened the Carlists. The government took land from the Church and nobles. This made these powerful groups angry. However, the Church and nobles were not the only ones threatened by liberalism. The push for a centralized Spain clashed with local authorities.

Special laws, called fueros, in the Basque Country were removed by the 1812 Constitution. They were mostly restored in 1814. But the conflict over self-rule in the Basque Country was a major issue. Catalonia and Aragon had lost their special laws after the War of the Spanish Succession in the early 1700s. They wanted them back. Carlists supported bringing back these old laws. This is why Catalonia and the Basque Country were central to the fighting.

The constant political problems during Queen Isabel II's reign convinced many traditionalists to start an armed uprising. After Isabella II was overthrown in 1868, a new king was sought. The choice of the Italian prince Amadeo I was not welcomed by the Carlists. They declared their leader, Carlos VII, as the true king. Spain was once again on the edge of a war for the crown.

The War Begins

Opposing Plans

Carlist Strategy

The Carlists planned to fight using small groups of fighters. These groups would use guerrilla warfare, attacking telegram posts, railways, and outposts with "hit and run" tactics. They avoided big cities like Bilbao because they were not strong enough to capture them. Instead, they were good at attacking undefended towns.

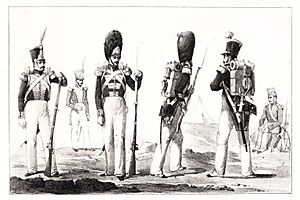

The Carlists also had some larger armies. These armies were made of volunteers. However, these forces often lacked military training and discipline. They also had trouble getting horses, ammunition, and weapons. Their weapons were often old. Carlists could not use the railway system, which limited their movement. Because of these problems, Carlists tried to avoid direct battles with the Liberals. They relied on guerrilla warfare instead.

Liberal Strategy

The Liberals wanted to force the Carlists into direct battles. They knew their army had better training, equipment, and leaders. The Liberals controlled the railway system, which allowed them to move troops and supplies quickly. They also had experienced soldiers and officers. Big cities like Bilbao supported them.

However, the Liberal government was politically unstable. They also lacked money and resources to fight the Carlists.

Guerrilla attacks by the Carlists were hard to fight. The Carlists knew the land well, which helped them. The Liberals' advantages were not as useful in this type of fighting. However, the Carlists' focus on guerrilla warfare limited the fighting to certain areas of Spain. It was a difficult and costly task to stop the Carlist guerrillas. Only after the government became more stable under King Alfonso XII in 1874 did the Liberals start to win.

Outbreak of Fighting

The Carlists planned a general uprising across Spain. They hoped to get many new recruits. On April 20, Carlos VII named General Rada as the commander of the Carlist army. The uprising was set for April 21.

Thousands of volunteers, many without training or weapons, gathered in Orokieta-Erbiti, north of Navarre. They waited for Carlos to arrive. In Biscay, other groups also rose up. Several small groups started guerrilla attacks across Catalonia, Castile, Galicia, Aragon, Navarre, and Gipuzkoa.

On May 2, Carlos VII crossed into Spain from France and took command. But on May 4, 1,000 government troops attacked the Carlist camp in Orokieta. Carlos VII was forced to retreat to France. 50 Carlists were killed, and over 700 were captured. This battle almost ended the war as soon as it began.

The government's victory at Orokieta was a big setback for the Carlists. Carlists from Biscay surrendered and signed an agreement. However, Carlists in other parts of Spain, like Castile, Navarre, Catalonia, Aragon, and Gipuzkoa, kept fighting. The agreement signed in Amorebieta was rejected by both sides.

Meanwhile, in Catalonia, the uprising started earlier than expected. Joan Castell led 70 men and began gathering supporters. Rafael Tristany took command until Carlos VII replaced him with his brother, Infant Alfonso, in December 1872. At the same time, Carlist Pascual Cucala gained support in the Maestrat. By early 1873, Carlists had 3,000 men in Catalonia, 2,000 in Valencia, and 850 in Alicante.

The Carlist Advance

After their defeat in the Basque Provinces and Carlos VII's escape to France, Carlist forces regrouped. New leaders were appointed, including General Dorregaray. A new uprising was planned for December 18, 1872. Small groups of trained officers entered Spain to build a Carlist Army. New fighting groups were formed, like the one led by priest Manuel Santa Cruz. The second Carlist uprising was successful. By February 1873, the Carlist army had about 50,000 men across all fronts.

1873

In February 1873, King Amadeo I left the throne, and the First Spanish Republic was declared. General Dorregaray arrived to lead the Carlist army in the Basque Country. On May 5, Carlist forces won an important victory at Eraul (Navarre). They caused many casualties to the government army and took many prisoners. Three months later, Carlos VII entered the Basque Provinces. In August, Carlist forces captured Estella, making it their capital.

The Carlists continued to advance. Government general Moriones tried to attack Estella but was pushed back. Estella remained a Carlist stronghold until 1876. These battles strengthened the Carlist army and their morale.

Eastern Front

The Carlist cause in Catalonia, Aragon, Maestrat, and Valencia was successful from the start in 1872. The arrival of Infant Alfonso in December 1872 strengthened the Carlists. Other leaders also helped organize battalions. The first major battle was at Alpens on July 9. Carlist forces ambushed a government column, killing or capturing 800 men. Another important battle happened at Bocairente on December 22. A government force was attacked by a larger Carlist force. The government general, Valeriano Weyler, managed to win by leading a strong counter-attack.

1874

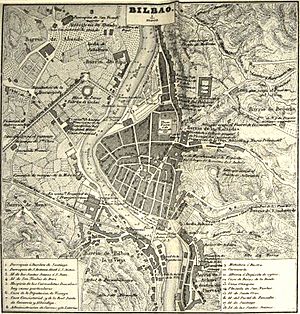

1874 was a turning point in this region. The Carlists failed to capture Bilbao, marking the limit of their advance. Encouraged by their successes and the unstable government, Carlists decided to attack Bilbao. They also sent a strong force to Gipuzkoa, capturing Tolosa on February 28. The siege of Bilbao lasted from February 21 to May 2, 1874. It was a brutal fight and a major turning point in the war.

Siege of Bilbao

The Carlist siege of Bilbao began on February 21, 1874. Carlists dug in around the city and cut off its supplies. Carlist attackers, led by Joaquin Elio and Carlos VII, had about 12,000 men. They faced 1,200 government soldiers and citizens of Bilbao. The Carlists started bombing the city, targeting food stores and markets. They hoped to make the citizens give up.

Government commanders tried to break the siege. On February 24, General Moriones led 14,000 men to relieve the city. But Carlist defenders pushed them back, causing many casualties. Another attempt was made in March, but it also failed. The siege was finally lifted on May 1, when government forces managed to outflank the Carlists. Serrano entered Bilbao the next day. The city was almost out of food.

Government Advance Against Estella

After breaking the siege of Bilbao, Marshal Serrano sent General Manuel Gutiérrez de la Concha to attack the Carlist capital of Estella. Carlist generals defended the city from nearby hills. Government forces, tired from their march, were pushed back after heavy fighting. They suffered over 1,000 casualties. By September 24, Carlists still held the Basque Provinces and most of Navarre. The government made more attempts to take Estella, but it remained a Carlist stronghold.

Eastern Front

1874 was also a turning point on the Eastern Front. It started with a small Carlist defeat in Caspe, Aragon. However, Carlists, with reinforcements, managed to set up a small state in the Maestrat. They defended the town of Cantavieja from several attacks but eventually surrendered after a siege.

In Catalonia, Carlist forces were very active. In March, a Carlist force captured Olot (Girona). Catalan Carlists then made Olot their capital. They formed a new government to rule the areas they controlled. Meanwhile, Infant Alfonso gathered a large Carlist army and marched to Cuenca. Cuenca fell after two days of siege and was badly looted. However, a government counter-attack defeated the Carlists, who then retreated. In October, disagreements among Carlist commanders weakened their forces.

Stalemate and the Fall of Catalonia

1875

The return of the monarchy on December 29, 1874, brought Alfonso XII to the throne. A former Carlist leader, Ramon Cabrera, announced his support for the new king. This greatly weakened the Carlist cause. Many high-ranking Carlist officers left and joined the government army. This caused distrust among the Carlists. From this point on, Carlists mostly fought to defend the areas they had already captured.

Basque Country

| "We know without a doubt that triggered by the extermination policy of the Alfonsino party and the unswerving faith of our brothers, the Basque-Navarrese Country would rather proclaim independence than kneel under sir Alfonso, should sir Charles VII surrender in the battlefield shrouded in his glorious flag." |

| Weekly periodical La bandera carlista, 19/09/1875 |

The return of the monarchy and internal disagreements hurt the Carlists. Many Carlist officers joined the government army. However, Carlists still showed their strength. On February 3, General Torcuato Mendiri surprised a government column near Lácar. In the battle, Carlists captured artillery, rifles, and prisoners. About 1,000 men died, mostly government troops. King Alfonso XII was with the column but escaped capture.

Despite this defeat, the Spanish government launched another attack in the summer of 1875. Government forces won a decisive victory over the Carlists at Treviño on July 7. General Quesada then entered Vitoria without a fight. Government forces continued their attack. Carlists used a "scorched-earth" tactic, burning crops and retreating. A change in Carlist leadership did not help. Even with a large army, the Carlists could not stop the government's advance.

Eastern Front

After the defeat at Cuenca and the departure of Infant Alfonso, the Carlist cause in Catalonia began to collapse. The government's attack on Olot in March and the siege of Seo de Urgel (which fell in August) sped up this process. By November 19, Catalonia was considered "pacified" and free of Carlist groups.

End of the War

1876

Having lost the war in Catalonia, the Carlists prepared for their last stand in the Basque Provinces and Navarre. The final battle was fought near Estella. Government forces, led by General Fernando Primo de Rivera, attacked in February 1876. Carlist forces built strong defenses on a nearby mountain, Montejurra.

The battle began on February 17. Carlist soldiers were forced to retreat, but they caused many casualties to the government forces. On February 19, government forces broke through the Carlist defenses and took Estella. Losing their capital convinced the remaining Carlists that their cause was lost. They began to go into exile. Carlos VII left Spain on February 28. On the same day, Alfonso XII entered Pamplona with a large army, ending the Third and final Carlist War.

Aftermath of the War

The end of the war brought a new political system to Spain. The new monarchy, set up in 1876, was based on the military and police. This system protected the interests of Spain's wealthy landowners and business owners.

A new idea of Spanish nationalism also grew. It focused on making Spain a strong, unified country. However, many Spanish citizens did not like this idea, leading to ongoing problems.

End of Self-Government

After the Third Carlist War, the special self-governing system of the Basque region was almost completely removed. The government army occupied the Basque Provinces. The Carlist defeat meant the end of the old Basque self-government.

However, in May 1876, the Spanish Prime Minister, Antonio Canovas del Castillo, had to negotiate with the Basque Provinces. These talks happened in secret. No agreement was reached. So, on July 21, 1876, a Spanish law was passed that removed the special system of Biscay, Álava, and Gipuzkoa. This law made the Basque provinces like other Spanish provinces. It also meant Basques had to join the Spanish military individually, not in separate groups. Many Basques struggled because they did not speak Spanish well.

Navarre was also affected, but less so. It had already become a Spanish province in 1841.

Basque Economic Agreement

The removal of the Basque special laws meant a new way to collect taxes was needed. The Basque leaders wanted to keep their self-rule. But under military occupation, they negotiated with the government. This led to the first Basque Economic Agreement in 1878. Under this system, Spanish tax collectors would not directly collect taxes from Basques. Instead, local councils would collect taxes and send a part of the money to the central government. This system is still used today.

This agreement helped calm regional feelings. It also created a strong base for industrial growth and a more stable central government.

Industrial Growth in the Basque Country

The Carlist defeat and the end of the Basque special system also led to more industry in the Basque Provinces, especially in Biscay. Mines, industries, and ports became more open to businesses. Many companies, especially British mining companies, came to Biscay. This led to a society based on iron ore mining.

This industrial growth had big effects. More people moved to Biscay, first from other Basque areas, then from all over Spain. As the number of factory workers grew, trade unions and the socialist movement became stronger. The industrialization also caused problems for Basque identity. Local customs and the Basque language seemed to be disappearing because of the many new immigrants. Along with the loss of their old government, this led to the rise of Basque nationalism.

The Restoration of the Monarchy

In December 1874, during the war, General Martinez Campos declared Alfonso XII as King of Spain. This ended the First Spanish Republic. Six years after his mother, Isabel II, was removed, the Bourbon royal family was back on the Spanish throne.

Before the monarchy was restored, Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, a leading politician, looked at the British monarchy as a model. He wanted a parliamentary system. Before the military uprising, Alfonso XII issued a statement, written by Canovas. It said that monarchy was the only way to end Spain's problems.

The 1876 Constitution

In the first months of the Restoration, Canovas held most of the power. To make his new government official, he needed a constitution. He organized elections to create a new constitution. It was based on earlier Spanish constitutions. The new constitution stated:

- Power would be shared between the king and the parliament.

- The King would have more power than the government.

- The parliament would have two parts and be controlled by a small, powerful group.

- Some individual rights and freedoms would be introduced.

- Catholicism would be the official state religion.

Alfonso's return to Spain and the new monarchy brought a long period of political stability. This system was based on conservative values, property, the monarchy, and a liberal state. Only two main parties were allowed to participate. The Conservative Party, led by Antonio Canovas del Castillo, represented landowners, businesses, Catholics, and old noble families. The Liberal Party, led by Práxedes Mateo Sagasta, represented those who accepted some changes. Both parties supported the monarchy.

The government was chosen through a system called the turno. The Conservative and Liberal parties would decide election results in advance. They would take turns governing to ensure support for the monarchy and prevent radical parties from gaining power. These parties often used unfair methods to win elections.

Basque Nationalism

One result of the end of Basque self-rule was the growth of Basque nationalism. A movement started to defend the lost Basque laws and culture, especially the Basque language. The 1894 Sanrocada protest in Biscay and the 1893–1894 Gamazada uprising in Navarre helped create the Basque Nationalist Party (EAJ-PNV). It was founded in 1895 by Sabino Arana, a Basque writer. Arana is seen as the father of Basque nationalism. He rejected the Spanish monarchy and based Basque nationalism on Catholicism and the fueros. The party's motto was:

Jaungoikoa eta Lagi zaharra ("God and Tradition").

The Basque Nationalist Party was conservative. It was against liberalism, industrialization, Spanish nationalism, and socialism. However, it attracted many people worried about losing Basque identity. By the end of the 19th century, the party won its first seats in local councils. Many votes came from rural areas and the middle class.

Catalan Nationalism

Catalan nationalism became very strong when Spain lost most of its colonies in 1898. Earlier in the 19th century, Catalan business owners worked with the central government. They even supported the return of the Bourbon monarchy in 1875.

Catalan federalist Valenti Almirall wrote one of the first ideas of Catalan nationalism in his 1886 book Lo Catalanisme. He believed a new political force, separate from Spanish parties, was needed. He created the party Centre Catalá in 1882. This party wanted more self-rule for Catalonia.

However, this idea did not go very far at first. Even in the late 19th century, Catalan nationalism was not very strong. Some wealthy Catalans supported Catalanism as a reaction to the Spanish government's centralizing policies. In 1887, Enric Prat de la Riba founded the "Lliga de Catalunya." In 1891, the Unió Catalanista was formed. This led to the first political plan for Catalanism in 1892, known as the Bases de Manresa. They demanded a regional self-governing power.

In Popular Culture

Paz en la guerra (Peace in War) (1895) is a novel by Miguel de Unamuno. It explores life and death through his childhood experiences during the Carlist siege of Bilbao. The writer Benito Pérez Galdós also mentions the Third Carlist War in his books Episodios Nacionales (1872–1912). He often showed Carlists as religious bandits.

The writer Joseph Conrad claimed he smuggled weapons to Spain for the Carlists. However, some scholars say this was just a story to make his smuggling tales more exciting.

Part of the film Vacas (1992) takes place during the Third Carlist War.

See also

In Spanish: Tercera guerra carlista para niños

In Spanish: Tercera guerra carlista para niños

- 1873 Montejurra battle (celebrated each year since)

- Traditionalist Communion – the Carlist political party from 1869 to 1937

- General Marco de Bello's biography

- Carlist anthem

- Carlist museum of Estella

Images for kids

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |