Manuel Santa Cruz Loidi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Manuel Santa Cruz Loidi

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Born |

Manuel Santa Cruz Loidi

1842 Elduain, Spain

|

| Died | 1926 Pasto, Colombia

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Known for | guerilla leader |

| Political party | Carlism |

Manuel Ignacio Santa Cruz Loidi (1842–1926) was a Spanish Catholic priest. He spent about 35 years working as a missionary in Colombia. He also held several small jobs in Jamaica for about 15 years.

However, he is most famous for what he did in 1872-1873. During a civil war in Spain, he led a Carlist guerilla group. People knew him as "cura Santa Cruz" (priest Santa Cruz) or simply "El Cura" (The Priest). He became known for being very harsh. In the late 1800s, he was seen as a symbol of wild brutality in Spain. He even appeared as a main character in some important Spanish books and plays from the early 1900s. He became a legendary figure long before he died.

Contents

Manuel Santa Cruz's Early Life

Manuel Santa Cruz Loidi came from Basque farming families. His ancestors lived in the Oria river valley in Gipuzkoa, near Tolosa. His father, Francisco Antonio Santa Cruz Sarove, married Juana Josefa Loidi Urrestarazu in 1824. They lived in Elduain, in a simple farmhouse called Zamonea. Manuel was not their only child; he had at least one sister.

Manuel grew up with his mother and step-father. At first, he was like any other village boy. Later, his older cousin, Francisco Antonio Sasiain Santa Cruz, who was a priest, helped him. He taught Manuel Latin and encouraged him to become a priest.

In 1861, Manuel started studying at the seminary in Vitoria. For the first three years, he got very good grades. But later, his grades dropped, possibly because of health problems. He became a priest in 1866 and was sent to Hernialde, a village close to his home. He later became the main priest there. He was very strict and lived a simple life himself.

Manuel's father had fought for the Carlists in an earlier civil war. Many people in rural Gipuzkoa also supported Carlism. So, Manuel likely grew up with strong Carlist beliefs. These beliefs probably became even stronger during his time at the seminary. Carlism was popular among priests in the area.

Santa Cruz strongly disliked the 1868 revolution. He preached against the new government, calling it unholy. His strong sermons caught the attention of the authorities. In October 1870, the Guardia Civil came to Hernialde to arrest him after Sunday Mass. Santa Cruz managed to escape and fled to France within a few days.

Leading a Guerrilla Group

After living in Bayonne, France, for about 18 months, Santa Cruz joined the guerrilla fighting. This happened before and during the Third Carlist War in 1872–73. His time as a fighter can be split into four periods: April-May 1872, June-August 1872, December 1872-July 1873, and December 1873. Between these times, he would hide in France.

At first, he joined a group led by Pedro Recondo, an experienced Carlist fighter. Santa Cruz served as a chaplain and learned about guerrilla tactics in the countryside. By the summer of 1872, he was leading his own group. It started with 15–25 men but grew to 200, 500, or even 1,000 fighters. His group was not fully part of the main Carlist army. They were told to "guard the Northern borderline" but mostly acted on their own.

Santa Cruz's group attacked the enemy's supply lines and small army posts. They stopped mail, arms shipments, and trains. They also raided small towns, destroying records, robbing Guardia Civil or Carabineros posts, and kidnapping local officials. This forced the Liberal army to use more soldiers for patrols instead of fighting on the front lines. However, Santa Cruz avoided big battles. When he did fight, like in Aia, he usually lost. If the enemy tried to surround him, he would break up his group and set a new meeting place. He knew the mountains of Gipuzkoa very well and had support from local people, which helped him avoid capture. Santa Cruz operated throughout Gipuzkoa and sometimes in nearby areas like Biscay, Álava, and especially Navarre.

By early 1873, Santa Cruz became known for being very cruel. He was accused of terrible acts. These included executing prisoners, even women or his own men if he suspected them of betrayal. He also burned down villages and used physical punishments.

One event that caused great anger happened in June 1873. Santa Cruz's men attacked a border control post in Endarlaza. He claimed the defenders had tricked them by showing a white flag and then firing again. So, Santa Cruz ordered his men to execute 35 carabineros who had surrendered. The Carlist leaders were already worried about Santa Cruz. The Endarlaza event was the final straw. General Antonio Lizarraga, the local Carlist commander, had been trying to control Santa Cruz. He demanded that the disobedient priest step down. In the end, Santa Cruz was being hunted by both the Liberals and the Carlists. He broke up his group and went back to France.

Life in France, Britain, and Jamaica

In France, Santa Cruz seemed lost. He spent over a year mostly in small villages in the French Basque country. Some of his old fighters wanted to start fighting again, but Lizarraga warned that Santa Cruz would be hunted if he did. The Spanish government asked France to send him back, but France refused. The Gendarmerie watched him closely, and he was even held in Bayonne once. He was pressured to leave France.

In late 1874 or early 1875, he went to a Jesuit college in Lille. With help from the Cambrai archbishop, Santa Cruz was forgiven by the Vatican. He was allowed to return to his duties as a priest, which he had stopped during the war. He wanted to become a missionary. To prepare, the Jesuits sent him to Britain to learn English. In early 1876, he met his king, Carlos VII, in London. Stories differ about this meeting. Some say Santa Cruz defended his actions during the war, while others say he regretted them and asked for forgiveness. Soon after, he sailed to Jamaica.

When he crossed the Atlantic, Santa Cruz stopped using his first family name. In America, he was known as Manuel Loidi. In December 1876, he was first recorded doing religious service in Jamaica. He later served in parishes like St. Andrews, Portland, and St. Mary, all in the eastern part of the island. He was listed as a "clergyman." Until the early 1880s, he mostly performed baptisms, marriages, and funerals, especially in King's Weston.

He served in five different mission stations and started nine new ones himself. Today, he is especially remembered for his work in the small village of Preston Hill. This was one of the first Catholic groups outside Kingston, mostly made up of descendants of former slaves. Santa Cruz is credited with building a wooden St. Francis Xavier church there, which served the community for many years. It seems that Santa Cruz and the Jesuits in Jamaica lived in extreme poverty. The local Catholic community was very poor and could barely support them. It is not clear why Santa Cruz left Jamaica in 1891 or 1892. It might have been because the mission's leadership changed. In the early 1890s, the Jamaica mission was given to the Maryland-New York Jesuit province, and American Jesuits took over.

Life in Colombia

It is not clear how Santa Cruz moved to Colombia. One story says an important Spanish Jesuit friend helped him. Santa Cruz agreed to join Colegio Javieriano, a Jesuit college and seminary in Pasto, the capital of Nariño department. He arrived in Pasto in 1892, possibly after spending some time in Panama.

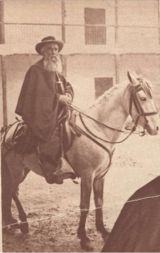

At the college, he taught English, French, Latin, geography, and math. His old, worn-out cassock (priest's robe) and long beard made him look like a beggar. He was not a member of the Jesuit order yet. His request to join was turned down, supposedly because his actions during the war needed a long period of penance. Santa Cruz was allowed to live in the monastery and follow its rules, but his official entry was put off until later.

Santa Cruz taught in Pasto until at least 1898. The next year, Colombia was in the Thousand Days' War. Pasto became a strong base for the Conservative party. Two strict bishops, Ezequiel Moreno Díaz and Pedro Schumacher, were very influential there. According to a Colombian historian, both bishops asked Santa Cruz for help. He was known for his strong anti-liberal sermons. Santa Cruz reportedly refused to lead military operations against the Liberal rebels. However, he did agree to help with planning and strategy. In this role, he was very successful.

After the Conservatives won the war in 1902, Santa Cruz founded the village of San Ignacio. It is located in the Andes mountains, about 20 km north of Pasto, in the county of Buesaco. For the second time since his time in Hernialde, he became a parson (a priest in charge of a parish). The village was home to very poor native people. It seems that besides providing religious services, Santa Cruz tried to help them financially. He taught the locals about farming. He also traveled around the county, begging for money to help the people of San Ignacio.

Santa Cruz spent about 18 peaceful years in San Ignacio. Some sources say he was greatly respected by the locals for his religious work, his humble nature, and his good life. His most lasting achievement was building the local San Ignacio church.

Santa Cruz kept his very conservative views. During local elections, he would tell his community how to avoid the corrupt voting system and vote for the candidates he thought were right. He also seemed to remain a Carlist. He wrote letters to his old war friends in Spain. In one letter, he promised loyalty to Don Jaime, the Carlist claimant to the throne. However, some suggest he also recognized Don Alfonso, the reigning king. In 1920, he was finally accepted into the Jesuit novitiate (a training period). In 1922, he officially joined the order. It is not clear where Santa Cruz spent his old age, whether in the Pasto monastery or in San Ignacio. He was eventually buried in the church he built in San Ignacio.

The "Black Legend"

Starting in January 1873, newspapers reported Santa Cruz's bad deeds. They called him an assassin, a criminal, or a barbarian. From 1874 to 1876, newspapers wondered if he would return to war. In the late 1870s, the media lost track of him. Then, in the mid-1880s, he was found in Jamaica, and his name brought back memories of past cruelties.

In 1880, he became a main character in a short novel called Vida, hechos y hazañas del famoso bandido y cabecilla Rosa Samaniego. This book, written by an unknown author, showed Santa Cruz as a bloody leader. It included many made-up stories and became very popular. It was reprinted until the early 1890s. Newspapers often mentioned Santa Cruz as an example of a disloyal priest. Sometimes, it was reported that he was back in Europe. When rumors of another Carlist uprising grew in the late 1890s, Santa Cruz was even reported to have been seen in Spain. The wildest rumor was that his son would lead a new Carlist group. A monument was built in Endarlaza to honor the carabineros he executed.

In 1897, Santa Cruz appeared in Paz en la guerra by Miguel de Unamuno. For about 20 years, he continued to be featured in major Spanish literary works. In 1906, he was written about more in Sonata de invierno by Ramón Valle-Inclán. In 1908, he was in Zalacaín el aventurero by Pio Baroja. In 1909, he appeared in two more novels by Valle-Inclán, El resplandor de la hoguera and Gerifaltes de antaño. In the latter, he was one of the two main characters. Finally, in 1918, Baroja wrote a collection of essays about him called El cura Santa Cruz y su partida.

The three great Spanish writers gave Santa Cruz different roles. Baroja saw Santa Cruz as a small man who hid his weaknesses with cruelty. He represented "double barbarity of being a Catholic and a Carlist." Unamuno believed Santa Cruz stood for a very strict way of thinking, whether religious or political. Unamuno rejected this idea, seeing Spanish identity as a mix of different ideas. Valle-Inclán's view was even more complex. Some say Valle-Inclán showed strong, sometimes monstrous, figures from the past to compare them with the weaker people of his time. Others think Valle-Inclán wanted to create a dark, dramatic mood with evil characters.

No matter their intentions, these writers, especially Baroja, turned the simple newspaper stories of Santa Cruz into a powerful literary image. This image included evil and demonic traits. This idea of Santa Cruz lasted into the 1930s, sometimes with new ideas added, like "fascist priest." In Francoist Spain, Santa Cruz's anti-Liberal stance made it hard to keep the "black legend" alive. After Spain's return to democracy, he was mostly forgotten. If people did remember him, their feelings were much more mixed.

The "White Legend"

At first, Carlism ignored Santa Cruz. As they tried to present themselves as a "party of order," Carlist politicians saw him as an awkward reminder of their past. But things changed after his death. In the late 1920s, three books were written defending him. Two of them had a Carlist viewpoint. Bernoville focused on Catholic regionalism, while Olazábal focused on Integrism. The third book, by Orixe, highlighted his Basque roots.

The challenging political situation of the Republic helped the Carlists reclaim Santa Cruz. For example, he appeared in poetry. When the civil war started, Carlist newspapers linked the bravery of their soldiers (Requetés) to Santa Cruz. The monument in Endarlaza was blown up by Carlist troops in July 1936, but it was quietly put back in 1940. Two major Carlist history books, written by Oyarzun in the 1940s and by Ferrer in the 1950s, wrote about El Cura carefully. In popular propaganda, he was sometimes praised, but he did not become a widely accepted hero.

Young people from the progressive part of the Comunión Tradicionalista tried to reclaim El Cura. In the early 1970s, their terrorist group GAC declared that "the flag of Santa Cruz has been raised again." Today, Santa Cruz is still mentioned on some private Carlist websites.

In the Basque-Navarre region, the Carlist supporters slowly shifted towards Basque nationalism. The radical part of this movement tried to change Santa Cruz's image. They turned his violence and strong beliefs into good qualities. El Cura began to appear in nationalist propaganda as a symbol of violent action. In the 1980s, the Herri Batasuna newspaper Egin published many long articles about El Cura. No nationalist figure dared to criticize him. As a result, newspapers noted "admiration of left-wing youth for legendary Santa Cruz." Baroja even said, "you can meet Cura Santa Cruz on any Basque street today."

The idea of El Cura as the spirit of "these mountains," unforgiving but idealistic, was shown in a 1990 Basque film by José Tuduri. A Basque historical study by Xabier Azurmendi also placed him deeply within the Basque background. Today, Santa Cruz is still present in nationalist discussions and on some websites, often linked with radical Left-wing politics. In 2008, a Basque band called Bizardunak released a song that celebrates the Santa Cruz myth. It is still publicly available and has references to ETA.

A new story about Santa Cruz began to appear in Colombia in the 21st century. The Fundación Manuel Santa Cruz Loydi was created to honor his work for the poor. It aims to preserve his memory as an excellent missionary who might have been close to being a saint. The organization is working to fix the old San Ignacio church. Its leader, historian Isidoro Medina Patiño, published two versions of a new biography in 2005. These books focused on Santa Cruz's time in America. Medina Patiño states that the usual ideas of "good or bad" about Santa Cruz "can be confused or changed." Both versions are very positive and show a man who spent his life helping others. He is also recognized in a Catholic encyclopedia for his similar work in Jamaica.

See also

In Spanish: Cura Santa Cruz para niños

In Spanish: Cura Santa Cruz para niños

- Traditionalism (Spain)

- Integrism (Spain)

- Carlism

- Carlism in literature

- Basque nationalism

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |