Melchor Ferrer Dalmau facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

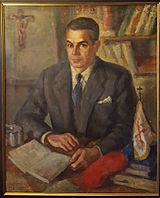

Melchor Ferrer Dalmau

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Melchor Ferrer Dalmau

1888 Mataró, Spain

|

| Died | 1965 Valencia, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | publisher, writer |

| Known for | historian, publisher |

| Political party | Carlism |

Melchor Ferrer Dalmau (1888–1965) was a Spanish historian and a strong supporter of Carlism. Carlism was a political movement in Spain that wanted a different branch of the royal family to rule and often supported traditional values.

Ferrer is best known for writing a huge, 30-volume book series called Historia del tradicionalismo español. This series is a very important reference for anyone studying Carlism. He was also a journalist, working as a chief editor for national and local newspapers that supported traditional ideas. Even though he wasn't very active in politics, he was sometimes part of the party's leadership. His support helped a more modern group within the Carlist party in the early 1960s.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Melchor Ferrer was born in Mataró, Spain, in 1888. His family, the Ferrers, were one of the oldest and most common names in Catalonia. They became important traders and bankers in the 1400s.

Melchor's father, Antonio Ferrer Arman (who lived from about 1845 to 1899), studied engineering. He later became a teacher at the Valldemia college, which was run by the Piarists, a religious order. Even though he liked some liberal ideas when he was young, he fought for the Carlists in the Third Carlist War. He became an officer in the army.

After the war, Antonio Ferrer Arman became the first headmaster of a new school in Mataró. He taught mathematics and was also a land surveyor. He wrote scientific books and was known as an intellectual who supported conservative Catholic Catalanism. Melchor's mother was Teresa Dalmau Gual, who came from Cuba.

Melchor was one of at least four children. His older brothers became engineers and started their own businesses. Melchor went to the Piarist college in Mataró and then to a school in Barcelona. He also studied engineering but never worked as an engineer. Instead, he started working for newspapers in 1910.

In 1920, Melchor married Paquita Rubio García. They did not have children together. However, Melchor and his sister-in-law had a son, Xavier Ferrer Bonet, who later became a Carlist activist. The famous painter Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau, who paints historical military scenes, is the great-grandson of Melchor's brother.

Journalism and World War I

Melchor Ferrer grew up in a Carlist family, so he joined the youth section of the Carlist movement in Barcelona. He was very interested in newspapers. He helped sell Carlist papers and was part of the propaganda group. In 1910, he joined the editorial team of El Correo Catalan, a Carlist newspaper in Barcelona. He worked there until 1914.

In 1914, Ferrer decided to join the French army to fight the Germans, even though he had no military experience. Some newspapers made fun of him. It's not entirely clear what happened, but some reports say he was arrested because the newspaper he worked for was seen as pro-German. He ended up serving in the Légion étrangère (Foreign Legion) in France and became a non-commissioned officer before leaving in 1918.

After the war, in late 1918 and early 1919, Ferrer spent time in Paris. There, he met the Carlist leader, Don Jaime. They got along well, and when Ferrer returned to Spain, he was made the political director of El Correo Español. This was the main Carlist newspaper in Madrid. His job was to make sure the newspaper stayed loyal to Don Jaime, as some people in the party were disagreeing.

Ferrer was successful in his mission. Even though many Carlists left the party, Correo remained loyal. Ferrer stayed in close contact with Don Jaime, traveling to Paris for meetings. He also attended a big Carlist meeting in Biarritz in 1919. He toured Spain to try and keep the Carlist organization together. He left Correo in mid-1920.

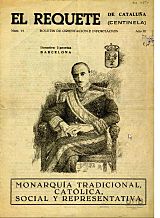

During the Dictatorship and Republic

Melchor Ferrer remained very loyal to Don Jaime. At some point in the 1920s, he became Don Jaime's personal secretary. He continued to write for many newspapers and magazines, including French ones. Some historians think he might have helped restart the Carlist military organization, the Requeté, across Spain. He might also have been involved in plans for a Carlist uprising in 1928, though Ferrer himself pointed to his older brother. He remained Don Jaime's secretary until the Carlist king died in late 1931.

In late 1930, Ferrer became the manager of Diario Montañes, a conservative newspaper in Santander that supported Traditionalism. He worked there for almost five years, and during this time, Carlism in the Cantabria region became stronger. Ferrer also gave many lectures at meetings. In 1931, he published a small book and wrote articles about Carlist history.

In early 1935, Ferrer moved to Andalusia and became the manager of Eco de Jaén. This was a new newspaper that replaced an older Traditionalist one. Ferrer made it a modern newspaper that fully supported Carlism. Like in Santander, he helped build up Carlist support by attending local meetings.

It is not clear if Ferrer knew about the Carlist plans for the 1936 coup. One writer says he was surprised by it. Eco de Jaén continued to operate until July 1936, when its offices were taken over. Ferrer lost his job and faced difficulties, but he survived the violence of the revolutionary terror in the Republican zone. He saw Jaén captured by the Nationalists in March 1939.

Life under Franco's Rule

After the Nationalists took over Jaén, Ferrer moved to Seville. He took over the local Carlist newspaper, La Unión, hoping to save it from strict censorship. However, the new government under Franco did not want any opposing newspapers. La Unión closed on December 31, 1939.

Ferrer's situation became worse when he refused to join the new state party, Falange Española Tradicionalista. As a result, his press license was taken away in 1941. It's not clear how he earned a living, but he eventually started teaching at the Escuela Náutica San Telmo and preparing students for military academy exams.

In the early 1940s, he began publishing Historia del tradicionalismo español. This book series became a source of income and quickly earned him great respect across Spain, even though he was not very well known before.

From the mid-1940s, Ferrer attended meetings of the National Carlist executive council. He was a close friend of the Carlist leader Manuel Fal Conde. Ferrer remained completely loyal to the Carlist regent, Don Javier, and used his writing to argue against other groups. His booklets, like Observaciones de un viejo carlista, defended Don Javier and criticized those who supported other royal heirs. He believed the Carlists should focus on getting popular support instead of trying to win over generals.

Ferrer was very loyal to the Borbón-Parma family, who were the Carlist claimants to the throne. He helped prepare documents that declared Don Javier as the rightful monarch in 1952. In 1955, he wrote another booklet, which was distributed by Carlist students, that criticized the idea of restoring a different royal family to the throne.

Later Years and Influence

Ferrer was concerned when the Carlist leader Fal Conde was dismissed in 1955. He warned about a plan to unite with another royal group, but he remained loyal to Don Javier and the new party leader, José María Valiente. By the late 1950s, Ferrer's historical writings were very extensive and earned him great respect within the Carlist party. He continued to attend executive meetings and helped write rules for the National Council. In 1961, he joined a new Culture Commission and wrote for its magazine, Reconquista, and other new Carlist publications like Montejurra.

Initially, Ferrer's influence on Carlist politics was small. He was seen more as a respected elder. However, this changed when differences appeared between the older Traditionalist members and the younger, more modern Carlist youth. Ferrer tended to side with the youth because of their strong loyalty to the Borbón-Parma family.

In 1961, he opposed efforts by older members to control Carlist propaganda. Ferrer also had a very good relationship with Don Javier's oldest son, Don Carlos Hugo, who led the youth movement. When some Traditionalists, led by José Luis Zamanillo, started to oppose Don Carlos Hugo's group, Ferrer confronted them. In 1962, he accused Zamanillo of not being active enough.

By 1963, the conflict between Zamanillo's Traditionalists and Don Carlos Hugo's supporters was in full swing. Ferrer used his authority to support Don Carlos Hugo. He wrote a memo accusing Zamanillo of plotting against the Carlist cause. Ferrer called himself "the bellboy of Carlism" and said he was happy to open the door for Zamanillo to leave. His strong stance might have changed the outcome, leading to Zamanillo's expulsion and Don Carlos Hugo's group gaining control of the party.

In his last years, Ferrer worked to strengthen Don Carlos Hugo's position. In 1964, he wrote a booklet to show that the Borbón-Parma family had rights to Spanish citizenship. He also drafted an analysis supporting their claim to the Spanish throne. This document was used at a large Carlist meeting in 1965, where Don Javier confirmed his royal claim. Ferrer was too ill to attend but was given a high Carlist honor, the Orden de la Legitimidad Proscrita.

Historian and Writer

Melchor Ferrer was trained as an engineer, and his main job was usually described as a journalist. He didn't show much interest in history until the mid-1930s, when he wrote a few articles about the Carlist past. Some people believe he started collecting materials for a general history of Carlism during the Spanish Civil War. Others say he started the project because Manuel Fal Conde suggested it in 1939. Fal Conde thought a history of Carlism was needed to help Carlists keep their identity under Franco's new government.

In 1941, Ferrer and two other writers, José F. Acedo Castilla and Domingo Tejera de Quesada, published the first volume of Historia del tradicionalismo español. This book was meant to be a complete, in-depth history of Carlism. The team continued to work on more volumes. Tejera died in 1944, but all 11 volumes published until 1949 were credited to all three authors. After Acedo left the Carlist movement, Ferrer was named the only author starting with volume XII.

Ferrer kept up the pace, publishing 18 volumes in 15 years until 1956. Over the next five years, he completed 11 more volumes. By 1960, he had released volume XXIX, bringing the story up to 1931. Ferrer continued working on new volumes, but he passed away before they were released. Volume XXX, which covered the period from 1931 to 1936, was published after his death in 1979 and was credited to Ferrer.

In total, Historia del tradicionalismo español is about 9,300 pages long. Each volume includes many pages of documents and a bibliography. The series focuses heavily on military history. For example, the First Carlist War is covered in 15 volumes, and the Third Carlist War in 4 volumes. A shorter version of this huge work was published by Ferrer in 1958, called Breve historia del legitimismo español.

Ideas and Theories

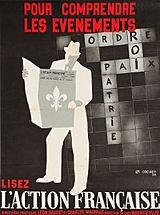

Compared to his massive history books, Ferrer's theoretical writings are fewer. They include two small books and several articles in Carlist magazines and daily newspapers. These writings show that Ferrer was interested in political theory. He is known as a Carlist thinker who was greatly influenced by integral nationalism, especially the ideas of Charles Maurras and his group, L'Action Française.

From a young age, Ferrer was impressed by Charles Maurras's writings. Some people believe his decision to join the French army in 1914 was due to his admiration for Maurras. Ferrer believed Carlism needed to be updated. He thought that Traditionalism in the 1920s was stuck in old ways. He wanted to combine Traditionalism with modern ideas.

Specifically, Ferrer tried to redefine the role of the nation and the state in Carlist thinking. Carlist thinkers usually didn't focus on these ideas, but Ferrer thought they were crucial for a modern outlook. He wanted them to be central to Carlist ideology. He also believed that the old liberal economic system was failing. His solution was a "corporate reorganization," where different social groups would work together.

In the 1930s, Ferrer agreed with Maurras that France was stuck in constant political problems and needed a strong leader. He disliked the idea of parliament, like the Nazis, but he disagreed with their nationalism based on race and their desire to control society. He preferred Italian Fascism, which he saw as opposing the ideas of 1789 (the French Revolution), liberalism, and individual rights. He liked that Fascism offered a way for all social interests to work together.

However, Ferrer believed that Spain, with its Traditionalist ideas, didn't need to copy foreign models. He admired L'Action Française but disliked its Spanish copy, Acción Española. He thought that Carlists involved in that project, like Pradera, had a limited view of Traditionalism. Ferrer also disliked the new government under Franco, seeing it as anti-Traditionalist. He had his own idea for how people should be represented in government. He thought it should be based on regional assemblies, each with four different chambers, following local traditions. These regional assemblies would then choose members for a national assembly, whose power would be limited to big issues like foreign affairs, the army, or money.

See also

In Spanish: Melchor Ferrer para niños

In Spanish: Melchor Ferrer para niños

Images for kids

-

Ferrer-Dalmau Nieto at work, 2013

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |