Charles Maurras facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Maurras

|

|

|---|---|

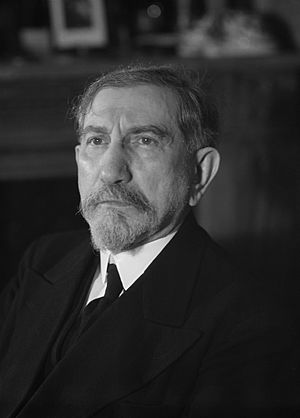

Maurras in 1937

|

|

| Born |

Charles-Marie-Photius Maurras

20 April 1868 Martigues, Bouches-du-Rhône, France

|

| Died | 16 November 1952 (aged 84) Tours, France

|

| Era | 20th century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

| Institutions | Action Française |

|

Notable ideas

|

Maurrassisme |

|

Influenced

|

|

Charles Maurras (20 April 1868 – 16 November 1952) was an important French writer, politician, poet, and critic. He was a main thinker and organizer of Action Française. This was a political group that wanted France to have a king again. They were also against too much power in parliament and believed in strong national pride.

Maurras held strong views against communism, secret societies (like Freemasons), Protestants, and Jewish people. However, he was very critical of Nazism, calling it "stupidity." His ideas greatly shaped "integral nationalism," which means putting your country above everything else.

Maurras was raised Catholic but became agnostic (someone who isn't sure if God exists) when he was young. Still, he supported the Catholic Church politically. His ideas were not liked by Pope Pius XI, but some other popes and religious figures had mixed or positive views. He became active in politics during the Dreyfus Affair, a big scandal in France. In 1926, Pope Pius XI officially spoke out against Action Française, but this ban was removed in 1939.

In 1936, Maurras was sent to prison for eight months for threatening a politician named Léon Blum. During World War II, Maurras supported Vichy France, the French government that worked with Nazi Germany. He wrote articles against Jewish people but was against Vichy's plan to deport them. After the war, he was arrested and accused of working with the enemy. He was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. In 1951, he became ill and was moved to a hospital, then later pardoned. Before he died, he returned to the Catholic faith.

Maurras was a major right-wing thinker in 20th-century Europe. He influenced many political ideas, including some that led to fascism. He is seen as a very important French conservative thinker. Many politicians, writers, and thinkers were influenced by him. Today, Maurras remains a very controversial figure. Some criticize him for his anti-Semitic views and support of Vichy France, calling him a "fascist icon." Others praise him. French President Emmanuel Macron said he fights Maurras's anti-Semitic ideas but finds it "absurd to say that Maurras must no longer exist."

Contents

Charles Maurras: Early Life and Political Beginnings

Growing Up and Early Writings

Charles Maurras was born into a family in Provence, France. His mother and grandmother raised him in a Catholic home that supported the idea of a king. When he was a teenager, he became deaf. Like many French people, he was deeply affected by France's loss in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.

At 17, Maurras published his first article. He then wrote for various magazines, where he praised Classicism (old Greek and Roman styles) and criticized Romanticism (a style focused on feelings and nature). Around this time, he lost his Catholic faith and became agnostic.

Influences and New Ideas

In 1887, Maurras moved to Paris and started writing about books. He was influenced by the idea of a king (Orleanism) and German philosophy. He also met the poet Frédéric Mistral and agreed with his idea of federalism, which means giving more power to local regions. In 1888, he met the nationalist writer Maurice Barrès.

In 1890, Maurras supported the idea of Catholics accepting the French Republic. This showed his opposition was not to the Republic itself, but to what he saw as "sectarian Republicanism." He also shared some ideas with Bonapartism, a movement that wanted a strong leader like Napoleon.

Getting Involved in Politics

Maurras became deeply involved in politics during the Dreyfus Affair. This was a major political scandal in France where a Jewish army officer, Alfred Dreyfus, was wrongly accused of treason. Maurras was against Dreyfus. He believed that defending Dreyfus would weaken the French Army and justice system.

Maurras thought Dreyfus should be sacrificed for the good of the nation. While others criticized Dreyfus because he was Jewish, Maurras went further. He attacked the "Jewish Republic" itself. He believed in "state anti-Semitism," which meant the government should be prejudiced against Jewish people.

In 1898, Maurras helped start the Ligue de la patrie française, a group against Dreyfus. In 1899, he founded the magazine Action Française (AF). He quickly became a leader in this movement. He convinced others to support the idea of bringing back a king, which became the main goal of AF.

The Action Française combined strong nationalism with traditional, old-fashioned ideas. It moved the idea of nationalism, which used to be supported by left-wing groups, to the political right. In 1908, the magazine became a daily newspaper. Maurras also wrote articles supporting monarchy.

Between 1905 and 1908, Maurras helped create the Camelots du Roi, a group that used direct action. He suggested that political change could happen through groups outside of parliament, even hinting at a possible coup d'état (a sudden takeover of the government). Many early members of Action Française were Catholics. They helped Maurras develop the group's pro-Catholic policies.

Charles Maurras: World Wars and Later Life

World War I and Beyond

Maurras supported France joining World War I against Germany. During the war, he accused a Jewish businessman of being a German agent, forcing him to resign from a bank. After the war, he criticized the Treaty of Versailles for not being tough enough on Germany.

In 1925, Maurras called for violence against the Interior Minister, Abraham Schrameck. For this, he was fined and given a suspended jail sentence. He also threatened Léon Blum, the first Jewish French prime minister, in 1936. This threat earned him eight months in prison.

During the 1930s, many members of Action Française became interested in fascism. Maurras himself supported Francisco Franco in Spain and, for a time, Benito Mussolini's Fascist government in Italy. He was against Adolf Hitler because he was anti-German. Maurras also criticized the racist policies of Nazism in 1936.

In 1938, Maurras was elected to the prestigious Académie française, a group of important French writers and thinkers.

World War II and Arrest

In June 1940, Maurras praised General Charles de Gaulle. However, he later strongly supported Philippe Pétain and the Vichy France government. This government cooperated with Nazi Germany during World War II. Maurras believed that France needed to fix itself politically and morally under Pétain before dealing with the German occupation.

He also wrote articles against Jewish people during this time. However, he was against Vichy's plans to deport Jews. Maurras claimed he thought Pétain was secretly working for the Allied victory.

After France was liberated from German occupation in 1944, Maurras was arrested. He was accused of "complicity with the enemy" (working with the enemy) because of his wartime writings. He was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. Maurras famously exclaimed, "It's Dreyfus's revenge!" after his conviction.

Historians suggest that Maurras's trial was political and unfair. The people chosen for the jury were often his political enemies. His seat in the Académie française was declared empty, but he was not officially expelled until after his death.

Final Years

Maurras was held in different prisons. He was released in March 1952 due to illness and transferred to a hospital. He continued to write for a new version of the Action Française magazine. He died in a clinic in Tours soon after. In his last days, he returned to the Catholic faith he had left in his youth.

Charles Maurras: Ideas and Influence

Maurras and Regional Culture

Maurras was born in Provence and joined Félibrige. This was a group started by Frédéric Mistral and other writers to protect and promote the Occitan languages and literature of the region.

Maurras's Political Thinking

Maurras's political ideas were based on strong nationalism, which he called "integral nationalism." He believed in an orderly society with a powerful government. This led him to support a French monarchy and the Roman Catholic Church.

He had a very active political approach. He wanted to change history, not just preserve it. His "integral nationalism" rejected democratic ideas. He thought they went against "natural inequality." He criticized everything that happened since the French Revolution of 1789. He wanted to bring back a king who would inherit the throne.

Maurras was worried about France "declining." He felt France had lost its greatness after the 1789 Revolution. He believed this greatness came from France's history as part of the Roman Empire and from "forty kings who in a thousand years made France." He saw the French Revolution as negative and destructive.

He traced this decline even further back, to the Age of Enlightenment and the Protestant Reformation. He blamed "Swiss ideas," referring to John Calvin and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Maurras also blamed "Anti-France" for the country's problems. He defined this as "Protestants, Jews, Freemasons, and foreigners." He saw the first three groups as "internal foreigners."

Prejudice against Jewish people and Protestants were common themes in his writings. He believed that the Reformation, the Enlightenment, and the French Revolution made individuals value themselves more than the nation. He thought democracy and liberalism were making things worse.

Even though Maurras wanted to bring back a king, his reasons were unusual. He supported the monarchy and Catholicism for practical reasons. He thought a state religion was the only way to keep public order. He believed the Church held France together and connected all French people.

Maurras claimed his ideas were based on reason, not feelings. He admired the philosopher Auguste Comte, who focused on scientific observation. Maurras was ready to take political action, even using street violence. His main slogan was "La politique d'abord!" ("Politics first!").

His religious views were also unusual. He supported the Catholic Church because it was part of French history. He also liked its strict, organized structure. However, he didn't trust the Gospels, calling them written "by four obscure Jews." He admired the Catholic Church for supposedly hiding some of the Bible's "dangerous teachings."

Many Catholic leaders criticized Maurras's ideas. But he gained many followers among French people who wanted a king and Catholics. However, his agnosticism worried some Catholic leaders. In 1926, Pope Pius XI put some of Maurras's writings on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (a list of forbidden books). The Pope also condemned the Action Française movement. This ban surprised many of his followers and hurt the movement. The ban was lifted by Pope Pius XII in 1939.

Lasting Influence

Maurras had a big impact on ideas like "national Catholicism," far-right movements, and "integral nationalism." He and Action Française influenced many people and groups. This included leaders like Francisco Franco in Spain and Léon Degrelle in Belgium.

His influence also reached Latin America. For example, in Mexico, Jesús Guiza y Acevedo was called "the little Maurras." In Argentina, he influenced nationalist writers in the 1920s and 1930s. More recently, in 2017, it was reported that Steve Bannon, a former advisor to President Donald Trump, admired Maurras.

Works

|

|

- 2016: The Future of the Intelligentsia & For a French Awakening, Arktos Media. ISBN: 978-1910524985

|

See also

In Spanish: Charles Maurras para niños

In Spanish: Charles Maurras para niños