Contemporary philosophy facts for kids

Contemporary philosophy is the most recent period in the history of Western philosophy. It began in the early 1900s. During this time, philosophy became more of a professional job, and two main types of philosophy grew popular: analytic philosophy and continental philosophy.

The term "contemporary philosophy" is a special phrase in philosophy. It means the philosophy of the 20th and 21st centuries. People sometimes confuse it with modern philosophy (which is an older period) or postmodern philosophy (which criticizes modern ideas). Sometimes, people just use "contemporary" to mean any recent philosophical work, but in philosophy, it refers to this specific time.

Contents

Becoming a Professional Philosopher

Becoming a professional means that a job or hobby turns into a formal career. It gets rules for how people should act, what skills they need, and groups to oversee them. For philosophy, this meant big changes.

How Philosophy Became a Profession

In the past, philosophers often wrote books for anyone interested. But as philosophy became a profession, things changed. Now, philosophers usually write short, technical articles for other philosophers. These articles appear in special journals. This shift happened around the late 1800s. It is a key difference for contemporary philosophy.

Germany was the first country where philosophy became a profession. In 1817, Hegel was the first philosopher to be appointed a professor by the government. In the United States, philosophy became professional through changes in universities, much like in Germany. England also saw similar changes in its higher education.

Today, most philosophical work is done by university professors. They usually have a doctorate degree in philosophy. They publish their work in special journals that are reviewed by other experts. Many people still have their own "philosophy" about life or politics. But these personal ideas are often not connected to the work done by professional philosophers. Unlike science, where many books and shows explain complex ideas to everyone, it's rare for professional philosophers to write for a general audience.

Philosophy Today: Professional Groups and Journals

The main group for philosophers in the United States is the American Philosophical Association. It has three parts: Pacific, Central, and Eastern. Each part holds a big meeting every year. The Eastern Division Meeting is the largest. It brings together about 2,000 philosophers each December. This meeting is also where many universities look for new philosophy teachers. The association also gives out important awards in philosophy.

There are many academic journals where philosophers publish their work. Here are some of the top "general" philosophy journals in English, based on a 2018 survey:

- Philosophical Review

- Mind

- Nous

- Journal of Philosophy

- Philosophy & Phenomenological Research

- Australasian Journal of Philosophy

- Philosophers' Imprint

- Philosophical Studies

- Philosophical Quarterly

- Analysis

For continental philosophy, a 2012 survey listed these as top journals in English:

- European Journal of Philosophy

- Philosophy & Phenomenological Research

- Journal of the History of Philosophy

The Philosophy Documentation Center publishes a "Directory of American Philosophers". This book lists information about philosophy in the United States and Canada. It comes out every two years. Another book, the "International Directory of Philosophy and Philosophers", covers philosophy around the world.

Since the early 2000s, philosophers have also started using blogs more often. These blogs help them share ideas and discuss topics. For example, philosopher David Chalmers started a list of philosophy blogs. Some blogs, like PEA Soup, even work with journals to discuss articles online. Blogs like What is it Like to be a Woman in Philosophy? have also helped highlight the experiences of women in the field.

The Analytic–Continental Divide

Contemporary philosophy is often split into two main traditions: analytic philosophy and continental philosophy.

How the Divide Started

Continental philosophy began with thinkers like Franz Brentano, Edmund Husserl, and Martin Heidegger. They developed a method called phenomenology. Around the same time, Gottlob Frege and Bertrand Russell started a new way of thinking. They focused on analyzing language using modern logic. This led to the term "analytic philosophy."

Analytic philosophy is most common in English-speaking countries like the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia. Continental philosophy is more popular in Europe, including Germany, France, and Italy.

Some philosophers, like Richard Rorty, believe this split is bad for philosophy. Others, like John Searle, think continental philosophy is too unclear.

Both analytic and continental philosophy share a common history up to Immanuel Kant. After Kant, their paths diverged. For example, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel is very important to many continental philosophers. But analytic philosophers see him as less central to their work.

Analytic Philosophy

Analytic philosophy usually started with Bertrand Russell and G.E. Moore in the early 1900s. They built on the ideas of Gottlob Frege. They moved away from older ideas like Hegelianism. Instead, they focused on analyzing concepts using new logic. Russell's 1905 paper "On Denoting" is a famous example of this new method.

Today, analytic philosophers have many different interests and methods. But their style is often very precise and detailed. They focus on narrow topics and avoid vague discussions of big ideas.

Some analytic philosophers, like Richard Rorty, have suggested that analytic philosophy should change. Rorty believes analytic philosophers can learn important lessons from continental philosophers.

Some people have simple ideas about these two types of philosophy. They might think analytic philosophers focus on small, easy problems with great detail. And they might think continental philosophers get big results but use unclear arguments. While these are "crude stereotypes," some philosophers admit that sometimes analytic philosophers might rush to big conclusions without enough strong arguments.

Continental Philosophy

The history of continental philosophy usually begins in the early 1900s. This is because its roots come from phenomenology. So, Edmund Husserl is often seen as its founder. However, because analytic and continental philosophy have such different views after Kant, continental philosophy can also include any post-Kant philosophers or movements important to it, but not to analytic philosophy.

The term "continental philosophy" covers many different ideas and approaches. Some even say it's more of a label for philosophies that analytic philosophers don't like. But there are some common features that often describe continental philosophy:

- First, continental philosophers usually disagree with scientism. This is the idea that natural sciences are the only or best way to understand everything.

- Second, continental philosophy often believes that our experiences are shaped by things like context, time, language, culture, or history. This means they often look at philosophy through its history. Analytic philosophy, however, tends to look at problems separately from their historical roots.

- Third, continental philosophers are very interested in how ideas connect to real life. They often see their philosophical questions as linked to personal, moral, or political changes.

- Fourth, continental philosophy often focuses on metaphilosophy. This is the study of what philosophy is, what it aims to do, and how it should be done. Analytic philosophy also does this, but with different results.

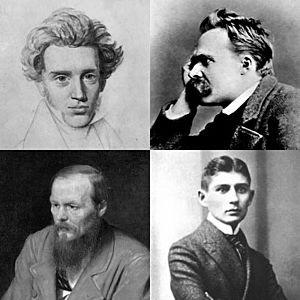

Another way to understand continental philosophy is by looking at some of its main movements. These include German idealism, phenomenology, existentialism (with thinkers like Kierkegaard and Nietzsche), hermeneutics, structuralism, post-structuralism, deconstruction, French feminism, and the critical theory of the Frankfurt School.

Bringing the Two Sides Together

More and more philosophers today are questioning if it's helpful to keep analytic and continental philosophy separate. Some, like Richard J. Bernstein and A. W. Moore, have tried to bring these traditions closer. They look for shared ideas among important thinkers from both sides.

See also

In Spanish: Filosofía contemporánea para niños

In Spanish: Filosofía contemporánea para niños

- Analytic philosophy

- Experimental philosophy – A new field that uses surveys and data to study old philosophical questions.

- Logical positivism – The first main school in analytic philosophy in the early 1900s.

- Naturalism – The idea that the scientific method is the only good way to understand reality.

- Ordinary language philosophy – The main school in analytic philosophy in the mid-1900s.

- Continental philosophy

- Deconstruction – A way of reading texts to show they have many different, sometimes clashing, meanings.

- Existentialism – A philosophy that starts with feeling lost or confused in a world that seems to have no meaning.

- Phenomenology – Focuses on understanding the structures of our consciousness and how things appear to us.

- Poststructuralism – Ideas that came after structuralism, questioning the idea of fixed underlying structures in culture.

- Postmodern philosophy – Questions many traditional ideas and values from modern philosophy.

- Social constructionism – The idea that some concepts or practices are created by a specific group of people.

- Critical theory – Looks at and criticizes society and culture using ideas from social sciences and humanities.

- Frankfurt School – A group of thinkers connected to the Institute for Social Research.

- Western philosophy