John Searle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Searle

|

|

|---|---|

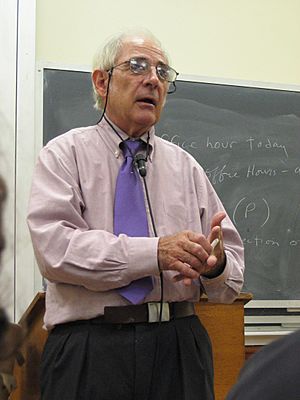

Searle at Christ Church, Oxford, 2005

|

|

| Born |

John Rogers Searle

July 31, 1932 Denver, Colorado, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | University of Wisconsin–Madison Christ Church, Oxford |

| Spouse(s) | Dagmar Searle |

| Era | Contemporary philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Analytic Direct realism |

| Institutions | Christ Church, Oxford UC Berkeley |

| Thesis | Problems arising in the theory of meaning out of the notions of sense and reference (1959) |

| Academic advisors | Peter Strawson J. L. Austin |

| Doctoral students | Bence Nanay |

| Other notable students | William Hirstein |

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

Indirect speech acts Chinese room Biological naturalism Direction of fit |

| Signature | |

John Rogers Searle (July 31, 1932 – September 17, 2025) was an American philosopher. He was known for his important ideas about language, the mind, and how society works. He started teaching at UC Berkeley in 1959. He was a professor there until June 2019, when his professor emeritus title was removed.

As a student at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Searle was involved in student groups. He earned all his university degrees from the University of Oxford in England. Later, at UC Berkeley, he was one of the first professors to support the Free Speech Movement in the 1960s. He also played a role in changing rent control rules in Berkeley in the early 1990s.

Searle received several major awards for his work. These included the Jean Nicod Prize in 2000 and the National Humanities Medal in 2004. His early work focused on how we use language, called "speech acts." He is perhaps most famous for his "Chinese room" argument. This idea challenges the belief that computers can truly "think" or "understand" in the same way humans do.

Contents

- About John Searle

- Searle's Big Ideas

- Awards and Honors

- Images for kids

- See also

About John Searle

Early Life and Education

John Searle's father, G. W. Searle, was an electrical engineer. His mother, Hester Beck Searle, was a physician.

Searle began his college studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. During his third year, he received a special scholarship called a Rhodes Scholarship. This allowed him to study at the University of Oxford in England. He completed all his university degrees there.

He later became a professor at the University of California, Berkeley. He retired in 2014 but continued teaching until 2016. In June 2019, his special title of professor emeritus was removed.

His Time at Berkeley

While in college, Searle was part of a group called "Students against Joseph McCarthy." McCarthy was a powerful senator at the time. When Searle started teaching at Berkeley in 1959, he became involved in student movements. He was the first tenured professor to join the Free Speech Movement in 1964–65. This movement fought for students' rights to express their views on campus.

In 1969, he supported the university during a disagreement with students over People's Park. He also wrote a book in 1971 called The Campus War. In this book, he explored why there were so many student protests during that time.

In the late 1980s, Searle was involved in a legal case about rent control in Berkeley. He and other property owners wanted to change the rules about how much they could charge tenants. This led to a court decision in 1990 that changed Berkeley's rent policy.

After the September 11 attacks, Searle wrote about international conflicts. He discussed the need for a strong approach to foreign policy. He believed the United States faced ongoing challenges from groups opposed to it.

Key Achievements

Searle received five honorary doctorate degrees from different countries. He was also an honorary visiting professor at universities in China.

In 2000, he was awarded the Jean Nicod Prize. This is a major award in philosophy. In 2004, he received the National Humanities Medal from the U.S. government. He also won the Mind & Brain Prize in 2006. In 2010, he became a member of the American Philosophical Society.

Searle's Big Ideas

Searle's work explored many deep questions about how we think and communicate. He wanted to understand how our minds work and how we create social rules.

How We Use Language (Speech Acts)

Searle's early work focused on "speech acts." This idea looks at how we do things with words. For example, when you say "I promise," you are not just saying words; you are performing an action – making a promise.

He built on ideas from other philosophers like J. L. Austin. Searle explained that when we speak, our words have two main parts:

- Illocutionary force: This is the purpose or intention behind our words. Is it a statement, a question, a command, or a wish?

- Propositional content: This is the actual idea or information being shared.

What We Mean and What We Do

Think about these sentences:

- "Sam eats apples." (A statement)

- "Does Sam eat apples?" (A question)

- "Sam, eat apples!" (A command)

- "If only Sam ate apples!" (A wish)

All these sentences are about "Sam eating apples" (the propositional content). But they each have a different purpose (illocutionary force).

Searle also talked about "direction of fit." This describes how words relate to the world.

- When you state a fact, like "The sky is blue," your words are meant to match the world. If the sky isn't blue, your statement is wrong. This is "word-to-world" fit.

- When you give a command, like "Clean your room," you want the world to change to match your words. If the room isn't cleaned, the command isn't satisfied. This is "world-to-word" fit.

How Our Minds Work (Intentionality and Background)

Searle also studied "intentionality." This is the ability of our minds to be "about" things. When you think about a tree, your thought is "about" that tree.

What Our Minds Are "About"

For Searle, intentionality is a special power of the mind. It allows us to think about, represent, or symbolize things in the world around us. It's not just about maps or pictures, which only have a "derived" intentionality because someone made them to represent something. Our minds have the real thing.

The Unspoken Rules of Understanding

Searle introduced the idea of the "Background." This is a set of skills, habits, and ways of understanding that we have. These are not conscious thoughts themselves. But they help us make sense of the world and generate appropriate thoughts when needed.

For example, if someone says "cut the cake," you know to use a knife. If they say "cut the grass," you know to use a lawnmower. The request didn't mention the tool, but your Background knowledge helps you understand. This Background helps us fill in the unspoken details in what people say.

Understanding Consciousness

In his book The Rediscovery of the Mind, Searle discussed consciousness. He argued that many modern ideas about the mind tried to ignore or deny consciousness. But Searle believed consciousness is real.

Our Own Experiences

Searle said that consciousness is a real, personal experience. It is caused by the physical processes happening in our brains. He called this idea "biological naturalism." It means that our conscious experiences are a natural part of our biology, just like digestion or breathing.

He also explained that some things are "ontologically subjective." This means they can only exist as a personal experience. For example, the pain you feel is only experienced by you. A doctor can objectively say you have back pain (epistemically objective fact), but the pain itself is your subjective experience.

Computers and Thinking (The Chinese Room)

Searle's idea of biological naturalism suggests that to create a conscious being, we would need to copy the brain's physical processes. This goes against the idea of "Strong AI." Strong AI suggests that a computer can truly "understand" and have a mind if it's programmed correctly.

Can a Computer Really Understand?

In 1980, Searle presented his famous "Chinese room" argument. Imagine a person who doesn't know Chinese sitting in a room. They have a book of rules. Someone outside slides Chinese characters under the door. The person inside follows the rules in the book to write down other Chinese characters and slides them back out.

To someone outside, it looks like the room understands Chinese. It takes Chinese input and gives back correct Chinese responses. But the person inside doesn't understand Chinese at all; they are just following rules. Searle argued that computers are like the person in the room. They can follow rules and process information, but they don't truly "understand" what they are doing.

How Society Works (Social Reality)

Searle also explored how things like "money" or "governments" exist in a world made of physical particles. He looked at how we create social reality.

Rules That Shape Our World

He explained "collective intentionality." This is when a group of people share an intention, like "we are going for a walk." This is different from just individual intentions.

Searle distinguished between "brute facts" and "institutional facts."

- Brute facts are things that exist independently, like the height of a mountain.

- Institutional facts are things that exist because we agree they do, like the score of a baseball game or the value of money.

He argued that society is built on institutional facts. These facts come from our shared intentions and "constitutive rules." These rules often follow the pattern: "X counts as Y in C." For example, a piece of paper (X) counts as money (Y) in our economic system (C). Or, putting a mark on a ballot (X) counts as a vote (Y) in an election (C).

Thinking Logically (Rationality)

In his book Rationality in Action, Searle challenged common ideas about rationality. He believed that thinking logically is not always like following a strict set of rules.

Why We Make Choices

Searle argued that reason doesn't force us to do things. Instead, we often feel a "gap" between our reasons and our actions. For example, you might know you should study, but you still have to choose to actually do it. This feeling of choice is what makes us think we have free will.

He also believed that we can do rational things even if they don't come from our desires. For instance, if you promise to do something, you have an obligation to do it, even if you don't really want to anymore. This obligation comes from the rules of making promises in our society.

Finally, Searle thought that being rational often means adjusting our desires. We balance different wants, like wanting to save money versus wanting to go on a trip. We then decide which desire is more important to us.

Awards and Honors

- Jean Nicod Prize (2000)

- National Humanities Medal (2004)

- Mind & Brain Prize (2006)

- Elected to the American Philosophical Society (2010)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: John Searle para niños

In Spanish: John Searle para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |