Bertrand Russell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bertrand Russell

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 18 May 1872 Trellech, Monmouthshire, UK

|

| Died | 2 February 1970 (aged 97) Penrhyndeudraeth, Wales, UK

|

| Era | 20th century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

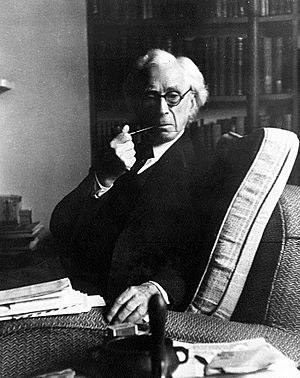

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, OM, FRS, (born May 18, 1872 – died February 2, 1970) was a very famous thinker. He was a philosopher, a logician (someone who studies how we reason), and a mathematician. He was born in Wales, but lived most of his life in England. He did most of his important work in the 20th century.

Bertrand Russell wrote many books and essays. He wanted to make philosophy easier for everyone to understand. He shared his opinion on many different topics. One of his most important essays was "On Denoting". He wrote about serious world issues and everyday life. Following his family's tradition, he was involved in politics. He was known as a liberal, a socialist, and an anti-war activist for most of his long life. Many people admired Russell for his ideas about thinking clearly and creatively. However, some of his opinions were quite debated.

Russell was a strong supporter of nuclear disarmament, which means getting rid of nuclear weapons. He did not support the American war in Vietnam, even when it was popular. In 1950, Russell won the Nobel Prize in Literature. He received it for his many important writings where he supported humanitarian ideas and freedom of thought. He passed away from influenza at 97 years old.

Contents

Who Was Bertrand Russell?

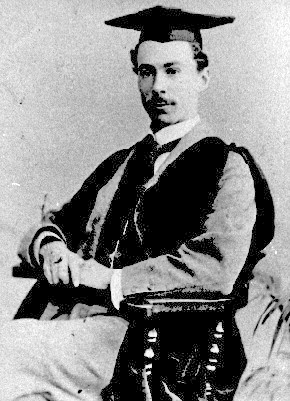

Bertrand Arthur William Russell was born on May 18, 1872, in Trellech, Monmouthshire, UK. His family was important and open-minded, belonging to the British aristocracy. His parents were John Russell, Viscount Amberley, and Katharine Russell. His grandfather, Lord John Russell, had been the prime minister twice in the 1840s and 1860s.

Bertrand had two older siblings, Frank and Rachel. Sadly, his mother and sister died when he was very young. His father also passed away a few years later. Bertrand and Frank then went to live with their grandparents at Pembroke Lodge. His grandfather died when Bertrand was six. His grandmother, Countess Russell, became the most important person in his life.

His grandmother was from a Scottish family and had strong beliefs. She made sure Bertrand was raised in a certain way. Even though she was religious, she had modern views on other things, like supporting Darwinism. Her influence helped shape Bertrand Russell's ideas about social justice and standing up for what is right. Her favorite Bible verse, "Thou shalt not follow a multitude to do evil," became his personal motto.

Russell's teenage years were lonely. He wrote that his love for "nature and books and (later) mathematics saved me from feeling completely sad." He was taught at home by tutors. When he was eleven, his brother Frank showed him the work of Euclid, which is about geometry. Russell said this was "one of the great events of my life."

Russell won a scholarship to study mathematics at Trinity College, Cambridge, and started there in 1890. He also taught about how societies are organized at the London School of Economics.

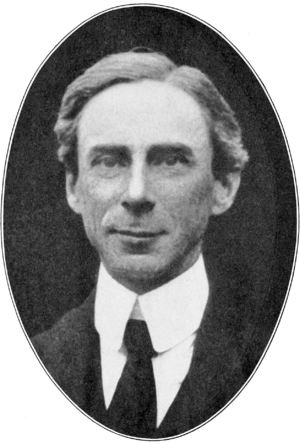

In 1905, he wrote an important essay called "On Denoting". In 1908, he became a Fellow of the Royal Society. Between 1910 and 1913, he wrote a three-volume book called Principia Mathematica with another scholar, Whitehead. These books made Russell very famous in his field. In 1910, he became a lecturer at Trinity College, Cambridge.

During World War I, Russell was one of the few people who actively spoke out against the war. Because of his strong anti-war views, he was removed from his teaching job at Trinity College in 1916. Later, he was briefly put in prison in 1918 for speaking publicly against the United States joining the war. He was able to return to Trinity College later.

In 1920, Russell traveled to Soviet Russia as part of a group looking into the Russian Revolution. He wrote articles about his trip and met Vladimir Lenin. He said he found Lenin disappointing. His experiences there made him change his mind about supporting the revolution. He then wrote a book about his trip called The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism.

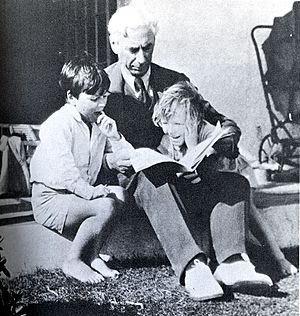

After his two children were born, Russell became very interested in early childhood education. He felt that traditional schools and even some new ones had problems. So, in 1927, he and his wife, Dora, started their own experimental school called Beacon Hill School. He also wrote a book called "On Education, Especially in Early Childhood".

Russell married four times. His fourth wife, Edith Finch, stayed with him until he died. Their marriage was a very happy one.

Before World War II, Russell taught at the University of Chicago and later at the UCLA Department of Philosophy. He also gave lectures on the history of philosophy, which became the basis for his famous book, A History of Western Philosophy.

In 1949, Russell received the Order of Merit, a special honor from the King. The next year, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Russell wrote his three-volume autobiography between 1967 and 1969. He also appeared as himself in an anti-war movie from India called Aman in 1967. This was his only movie role.

Bertrand Russell passed away from influenza on February 2, 1970, at his home in Penrhyndeudraeth, Wales, at the age of 97. His body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered over the Welsh mountains. Even though he was born and died in Wales, Russell thought of himself as English. A statue of Russell was later placed in Red Lion Square in London to remember him.

What People Said About Russell

As a Person

- "Bertrand Russell would not have wished to be called a saint of any description; but he was a great and good man."

- — A.J. Ayer, Bertrand Russell, 1972.

As a Philosopher

- "It is difficult to overstate the extent to which Russell's thought dominated twentieth century analytic philosophy: virtually every strand in its development either originated with him or was transformed by being transmitted through him. Analytic philosophy itself owes its existence more to Russell than to any other philosopher."

- — Nicholas Griffin, The Cambridge Companion to Bertrand Russell, 2003.

As a Writer

- "Russell's prose has been compared by T.S. Eliot to that of David Hume's. I would rank it higher, for it had more color, juice, and humor. But to be lucid, exciting and profound in the main body of one's work is a combination of virtues given to few philosophers. Bertrand Russell has achieved immortality by his philosophical writings."

- — Sidney Hook, Out of Step, An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century, 1988.

- "Russell's books should be bound in two colours, those dealing with mathematical logic in red — and all students of philosophy should read them; those dealing with ethics and politics in blue — and no one should be allowed to read them."

- — Ludwig Wittgenstein quoted in Rush Rhees, Recollections of Wittgenstein, 1984.

As a Mathematician and Logician

- Of the Principia: "...its enduring value was simply a deeper understanding of the central concepts of mathematics and their basic laws and interrelationships. Their total translatability into just elementary logic and a simple familiar two-place predicate, membership, is of itself a philosophical sensation."

- — W.V. Quine, From Stimulus to Science, 1995.

As an Activist

- "Oh, Bertrand Russell! Oh, Hewlett Johnson! Where, oh where, was your flaming conscience at that time?"

- — Alexandr I. Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, 1974.

About His Nobel Prize

- "In other words, it was specifically not for his incontestably great contributions to philosophy — The Principles of Mathematics, 'On Denoting' and Principia Mathematica — that he was being honoured, but for the later work that his fellow philosophers were unanimous in regarding as inferior."

- — Ray Monk, Bertrand Russell, The Ghost of Madness, p. 332.

From His Daughter

- "He was the most fascinating man I have ever known, the only man I ever loved, the greatest man I shall ever meet, the wittiest, the gayest, the most charming. It was a privilege to know him, and I thank God he was my father."

- — Katharine Tait, My Father Bertrand Russell, 1975, p. 202.

Famous Sayings

- "War does not determine who is right. Only who is left." (Often said to be by Russell, but no clear source.)

- "The secret of happiness is to face the fact that the world is horrible, horrible, horrible." (Source: Alan Wood, Bertrand Russell, the Passionate Sceptic, 1957)

- "The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, but wiser people so full of doubts." (Source unknown)

- "You could tell by his Aldous Huxley conversation which volume of the Encyclopaedia Britannica he'd been reading. One day it would be Alps, Andes and Apennines, and the next it would be the Himalayas and the Hippocratic Oath." (Source: Parris, M., Scorn: With Added Vitriol, 1996, quoting Russell's 1963 letter)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Bertrand Russell para niños

In Spanish: Bertrand Russell para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |