Søren Kierkegaard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Søren Kierkegaard

|

|

|---|---|

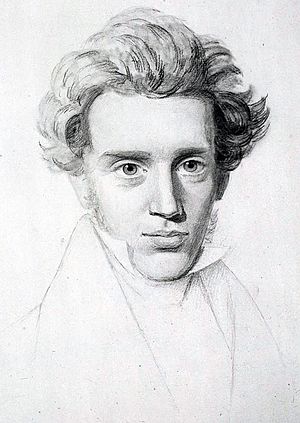

Unfinished sketch of Kierkegaard by his cousin Niels Christian Kierkegaard, Royal Library, Copenhagen, c. 1840

|

|

| Born |

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard

5 May 1813 |

| Died | 11 November 1855 (aged 42) Copenhagen, Denmark

|

| Education | University of Copenhagen (M.A., 1841) |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

| Thesis | Om Begrebet Ironi med stadigt Hensyn til Socrates (On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates) (1841) |

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

|

| Signature | |

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard (born May 5, 1813 – died November 11, 1855) was a Danish thinker. He was a philosopher, a theologian, a poet, and a writer. Many people see him as the first existentialist philosopher.

Kierkegaard wrote about many important topics. These included organized religion, Christianity, morality, and psychology. He liked to use metaphors, irony, and parables in his writing. His main idea was about how each person lives as a "single individual." He believed that real human experiences and choices are more important than abstract ideas.

He often wrote using different fake names, called pseudonyms. This helped him explore complex ideas from many different angles. He also wrote books under his own name, which he called Upbuilding Discourses. These were meant to help people understand his other works.

Some of Kierkegaard's key ideas include "subjective and objective truths" and the "leap of faith." He also wrote about angst (a feeling of deep worry or dread). His books were first popular in Scandinavia. Later, they were translated into other languages and became very influential around the world.

Contents

Søren Kierkegaard: His Early Life (1813–1836)

Søren Kierkegaard was born in Copenhagen, Denmark. His family was wealthy. His mother, Ane Sørensdatter Lund Kierkegaard, had been a maid before marrying his father, Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard. She was a quiet person and did not have much formal education.

Søren's father, Michael, was a successful wool merchant. He was a serious man but had a very active imagination. He loved philosophy and often invited thinkers to their home. Michael was very interested in the ideas of philosopher Christian Wolff. Søren was greatly influenced by his father's beliefs.

Søren also enjoyed the plays of Ludvig Holberg and the writings of Plato. The ancient Greek philosopher Socrates especially influenced Kierkegaard's later interest in irony.

Kierkegaard loved walking through the old streets of Copenhagen. He enjoyed talking to everyone he met, no matter if they were rich or poor. He wrote that he was happy to be someone "whom every poor person could freely accost and converse with on the street."

His father believed that his own past actions might bring bad luck to his children. Five of his seven children died before him. However, Søren and his older brother, Peter, lived longer than their father. Peter later became a bishop.

Søren Kierkegaard hoped that people would not hold onto their sins once they were forgiven. He believed that true faith in forgiveness would free people from fear. He wrote a prayer about this: "Father in Heaven! Hold not our sins up against us but hold us up against our sins."

From 1821 to 1830, Kierkegaard went to the School of Civic Virtue. He studied Latin and history there. He was described as "very conservative" and respectful of authority. He sometimes argued with other students.

He later studied theology at the University of Copenhagen. He was not very interested in traditional philosophy or just gaining knowledge. He wanted to understand "what am I to do," not just "what I must know." He wanted to live a truly human life.

In 1836, a friend described Kierkegaard as "almost comical." He was 23 years old and had unusual hair that stood up high on his forehead. His niece remembered him as slender and delicate. His father called him "fork" because of his sharp, satirical comments.

Søren's mother died in 1834. His father died in 1838. Søren wrote that he wished his father had lived longer. He felt his father was a "faithful friend."

His Engagement and Studies (1837–1841)

A very important part of Kierkegaard's life was his engagement to Regine Olsen. They met in 1837 and liked each other right away.

Kierkegaard proposed to Regine in 1840. But he soon felt unsure about getting married. He broke off the engagement in 1841. Many believe they were still deeply in love. Kierkegaard wrote in his journals that his "melancholy" (sadness) made him unfit for marriage.

He then focused on his studies. In 1841, he wrote his master's thesis, On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates. The university liked it but found it a bit too informal. He graduated with a Master of Arts degree. His family's inheritance allowed him to live and write without needing a job.

Søren Kierkegaard: His Writings (1843–1846)

Kierkegaard published many of his books using fake names, called pseudonyms. This was a way to show different ideas and viewpoints. He also published some books under his own name. His most famous works include Fear and Trembling and Either/Or.

His book Either/Or came out in 1843. It explored ideas about faith and marriage. It was like a debate between two characters, "A" and "B," who had different views. Kierkegaard wanted readers to think about how they understood things, not just what they read.

He also published Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1843 under his own name. These were not like sermons preached in church. Instead, they were meant to be conversations that would "build up" or encourage the reader. He believed that people should help each other grow, not tear each other down.

In 1843, he published Fear and Trembling and Repetition under pseudonyms. Repetition is about a young man dealing with worry and sadness. He wonders if psychology can help him. Kierkegaard used these books to explore complex feelings and ideas about faith and love.

He believed that understanding God's love depends on how one sees, not just what one sees. He wrote that "all observation is not just a receiving... but also a bringing forth." This means our own way of looking at things changes what we understand.

In 1844, he published more "upbuilding discourses." He also wrote philosophical books like Philosophical Fragments and The Concept of Anxiety. He believed that the question of God's existence is not just about arguments or proof. It's about each person making a choice to believe and live out that belief.

Kierkegaard thought that each generation has its own challenges. He believed that no generation can truly learn how to love or have faith from the one before it. Each person must start from the beginning and find their own way.

He was against the idea that a "third party" or system should come between a person and their desires or God. He stressed that people should choose to be content with God's grace. This choice involves "the temporal and the eternal," "mistrust and belief," and "subjective and objective" truths.

The Inwardness of Christianity

Kierkegaard believed that God connects with each person in a unique and personal way. He published Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions and Stages on Life's Way in 1845. He knew his books were not widely read, but he felt it was his duty to write them.

He used the idea of the "knight of hidden inwardness" to describe a religious person. This person looks like everyone else but has a deep, hidden inner life. Kierkegaard believed that people often hide their true feelings and thoughts. He wrote that only those who truly understand themselves can understand others.

He wanted people to stop just thinking about God and Christ. Instead, he wanted them to actually live as Christians. He was against waiting for proof of God's love before trying to be a Christian. He called this waiting a "special type of religious conflict."

Kierkegaard believed the Church should not try to prove Christianity. Instead, it should help people make a "leap of faith." This means believing that God is love and has a purpose for each person. He wrote that love, not fear, is the main driver in Christian life.

In 1846, he published Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments. In this book, he explained the purpose of his earlier writings. He said that Christianity is not just a human idea. It asks for a deep commitment, a "martyrdom of faith," which means trusting even when things are hard to understand.

Later thinkers have debated how to understand Kierkegaard's works. Some thought his pseudonyms represented his own changing views. Others believed each pseudonym had its own distinct viewpoint.

His Pseudonyms

Kierkegaard used many different pseudonyms (fake names) for his books. Each one represented a different way of thinking about faith and life. Here are some of his most important pseudonyms:

- Victor Eremita, editor of Either/Or

- Johannes de Silentio, author of Fear and Trembling

- Johannes Climacus, author of Philosophical Fragments and Concluding Unscientific Postscript

- Anti-Climacus, author of The Sickness unto Death and Practice in Christianity

These different authors explored the idea of faith. Kierkegaard believed that if people were confused about faith, they couldn't truly develop it. He thought that understanding faith meant understanding oneself, the world, and God.

The Corsair Affair

In 1845, a writer named Peder Ludvig Møller criticized Kierkegaard's book Stages on Life's Way. Møller wrote for The Corsair, a newspaper that made fun of famous people. Kierkegaard wrote a sarcastic reply, asking The Corsair to make fun of him directly.

The Corsair took his challenge seriously. For months, they published cartoons and articles making fun of Kierkegaard's looks and habits. Kierkegaard felt harassed on the streets. This experience made him rethink how he communicated his ideas.

In 1846, he openly admitted he was the author of his pseudonymous books. He also wrote Two Ages: A Literary Review. In this book, he criticized modern society for being too focused on fitting in. He believed that people were becoming too much alike, like a "mathematical equality."

Kierkegaard argued that newspapers and "the crowd" were making people lose sight of the truth. He believed that truth comes to each person individually, not to a large group all at once. He said, "never have I read in the Holy Scriptures this command: You shall love the crowd."

Søren Kierkegaard: Later Writings (1847–1855)

In 1847, Kierkegaard wrote Edifying Discourses in Diverse Spirits. He asked what it means to be a good person and to follow Christ. He continued to write "Christian discourses" that were meant to help people reflect on their lives.

He believed that deep emotions and feelings, like faith, hope, and love, are very important. He thought that endless thinking without passion was not enough. He wanted people to focus on their inner feelings, not just outward displays.

Kierkegaard believed that God meets each person in a mysterious way. He argued against trying to prove God's existence through logic. He thought that faith and love are like muscles – they get stronger when you use them.

Attack on the Church

In his final years, Kierkegaard openly criticized the Church of Denmark. He wrote newspaper articles and pamphlets called The Moment. These writings are now known as Attack Upon Christendom.

He started his attack after a bishop called a recently deceased leader a "truth-witness." Kierkegaard believed this was wrong because the Church had become too focused on rules and power, not true Christian living. He felt the Church was controlled by the state and cared more about having many members than about individuals' faith.

He argued that the Church made people act like children, not taking responsibility for their own relationship with God. He believed that "Christianity is the individual, here, the single individual." He thought that when the Church was tied to the state, it made Christianity a mere tradition, not a deep personal belief.

Søren Kierkegaard: His Death

Before he could publish the tenth issue of The Moment, Kierkegaard collapsed on the street. He stayed in the hospital for over a month. He refused to take communion from the church's pastors. He saw them as political officials, not true representatives of God. He told a friend that his life had been full of suffering.

Kierkegaard died on November 11, 1855. He may have died from problems related to a fall from a tree when he was young. Some suggest he died from a type of tuberculosis. He was buried in the Assistens Kirkegård in Copenhagen. At his funeral, his nephew protested the burial by the official church. He said Kierkegaard would not have approved, as he had criticized the Church.

Søren Kierkegaard: His Ideas

Kierkegaard is known as a philosopher, a theologian, and the "Father of Existentialism." Two of his most important ideas are "subjectivity" and the "leap of faith."

The Leap of Faith

The "leap of faith" is Kierkegaard's idea of how someone believes in God or acts in love. He believed that faith is not based on proof. No amount of evidence can fully explain the deep commitment needed for true religious faith or love. Faith means making that commitment anyway.

Kierkegaard thought that having faith also means having doubt. Doubt is the part of our mind that weighs evidence. Without doubt, faith would not be real. For example, it takes no faith to believe a pencil exists when you see it. But to have faith in God means believing even when you cannot see or touch God. He wrote, "doubt is conquered by faith."

Subjectivity is Truth

Kierkegaard also stressed the importance of the "self" and how it relates to the world. He believed this comes from thinking about oneself. He argued that "subjectivity is truth" and "truth is subjectivity." This means that how a person relates to a truth is as important as the truth itself.

For example, two people might both know that many people are poor and need help. But only one might choose to actually help them. Kierkegaard said that knowledge alone is not enough; it's about how you personally commit to that knowledge. He mainly talked about this idea in relation to religion.

Søren Kierkegaard: His Political Views

Kierkegaard is often seen as a philosopher who didn't focus on politics. However, he did write some political pieces. For example, he criticized the movement for "women's liberation" in an early essay. But in his later works, he showed great respect for women and believed men and women are equal before God.

He was against the ideas of Hegel, a famous German philosopher. Kierkegaard thought Hegel's ideas were too abstract and didn't focus enough on the individual.

Kierkegaard leaned towards conservative ideas. He was friends with the Danish king, Christian VIII. He argued against democracy, calling it "the most tyrannical form of government." He thought monarchy was better because "all want to rule" in a democracy, which he saw as a problem.

He also strongly disliked newspapers. He called the media "the most wretched, the most contemptible of all tyrannies." He believed that newspapers and "the crowd" made people lose sight of individual truth.

Søren Kierkegaard: His Legacy

Many thinkers in the 20th century were influenced by Kierkegaard. This includes philosophers and theologians, both religious and non-religious. His ideas about angst (dread), despair, and the importance of the individual became very popular. His fame grew a lot in the 1930s because he was seen as a key figure in the existentialist movement.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, a very important philosopher, said Kierkegaard was "by far the most profound thinker of the [nineteenth] century." Karl Popper, another famous philosopher, called Kierkegaard "the great reformer of Christian ethics."

Kierkegaard also had a big impact on literature. Writers like Franz Kafka, Hermann Hesse, and J.D. Salinger were influenced by his work.

He had a deep influence on psychology. He is seen as a founder of Christian psychology and existential psychology. Psychologists like Viktor Frankl and Rollo May were inspired by him. Rollo May even based his book The Meaning of Anxiety on Kierkegaard's The Concept of Anxiety.

Kierkegaard is considered by some to be the "Father of Existentialism." He predicted that his work would become very important after his death.

Images for kids

-

The Parable of the Good Samaritan described in works of love

-

Theodor Adorno in 1964

-

Jean-Paul Sartre in 1967

-

Portrait of Ludwig Wittgenstein who once stated that Kierkgaard was "by far the most profound thinker of the [nineteenth] century. Kierkegaard was a saint."

See also

In Spanish: Søren Kierkegaard para niños

In Spanish: Søren Kierkegaard para niños

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |