Martin Buber facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Martin Buber

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | February 8, 1878 |

| Died | June 13, 1965 (aged 87) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy Existentialism Neo-Hasidism |

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

Ich-Du (I–Thou) and Ich-Es (I–It) philosophy of dialogue |

|

Influenced

|

|

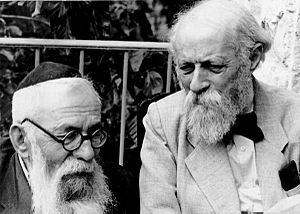

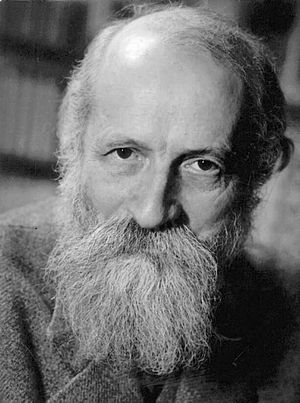

Martin Buber (Hebrew: מרטין בובר; German: Martin Buber; Yiddish: מארטין בובער; February 8, 1878 – June 13, 1965) was an Austrian Jewish and Israeli philosopher. He is famous for his "philosophy of dialogue." This idea is a type of existentialism, which focuses on the difference between "I–Thou" and "I–It" relationships.

Buber was born in Vienna into a Jewish family. However, he decided to study philosophy instead of following traditional Jewish customs. In 1902, he became an editor for Die Welt, a newspaper for the Zionist movement. Later, he stepped back from this work. In 1923, Buber wrote his well-known book, Ich und Du (meaning I and Thou). In 1925, he started translating the Hebrew Bible into German language, trying to keep the feel of the original Hebrew.

He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature ten times. He was also nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize seven times.

Contents

Martin Buber's Life Story

Martin Buber was born in Vienna into an Orthodox Jewish family. His Hebrew name was Mordechai. When he was three, his parents divorced. He was then raised by his grandfather, Solomon Buber, in Lemberg (now Lviv, Ukraine). His grandfather was a scholar of Jewish texts. At home, Martin spoke Yiddish and German. In 1892, he moved back to his father's house in Lemberg.

Even though he came from a religious family, Buber had a personal religious crisis. This led him to move away from traditional Jewish religious customs. He started reading books by famous philosophers like Immanuel Kant, Søren Kierkegaard, and Friedrich Nietzsche. These thinkers especially inspired him to study philosophy. In 1896, Buber began studying philosophy, art history, and German studies in Vienna.

In 1898, he joined the Zionist movement. This movement supported the idea of a Jewish homeland. He attended meetings and helped with the organization. In 1899, while studying in Zürich, Buber met Paula Winkler. She was a talented writer who later converted to Judaism and became his wife.

During World War I, Buber believed Germany had an important role to play. Some researchers think he was influenced by the writings of Jacob L. Moreno during this time.

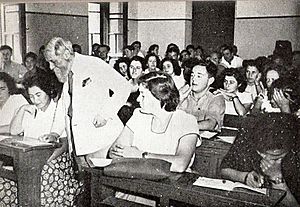

In 1930, Buber became a professor at the University of Frankfurt am Main. However, he resigned right away in 1933 when Adolf Hitler came to power. He did this to protest the new government. He then started the Central Office for Jewish Adult Education. This office became very important because the German government stopped Jews from attending public schools. In 1938, Buber left Germany and moved to Jerusalem, in what was then Mandatory Palestine. He became a professor at Hebrew University. He taught about people and societies. After Israel became a country in 1948, Buber became a very well-known Israeli philosopher.

Buber and Paula had two children, Rafael and Eva. They also helped raise their granddaughters, Barbara and Judith. Buber's wife, Paula, passed away in 1958. Martin Buber died at his home in Jerusalem on June 13, 1965. He was a vegetarian.

Main Ideas and Themes

Buber's writing style was often poetic. His main ideas included retelling Hasidic and Chinese stories. He also wrote commentaries on the Bible and discussed deep philosophical questions. Buber was a cultural Zionist. This meant he was active in Jewish and educational groups in Germany and Israel.

He strongly supported a plan for both Jewish and Arab people to live together peacefully in Palestine. After Israel was formed, he wanted Israel to be part of a group of countries in the region. His ideas have influenced many areas, including social psychology, social philosophy, and religious existentialism.

Buber's view on Zionism was linked to his idea of "Hebrew humanism." This term was used to show that his idea of Jewish nationalism was different from the official Zionist movement. He believed that Israel's challenges were part of bigger human problems. So, Israel's role as a nation was connected to the role of all humanity.

Martin Buber's Zionist Views

Buber had his own ideas about Zionism. He disagreed with Theodor Herzl, a key leader of Zionism, about its political and cultural goals. Herzl saw Zionism mainly as a political movement. Buber, however, believed Zionism should focus on making society and spirituality richer. For example, Buber thought that after Israel was formed, Judaism would need changes. He said, "We need someone who would do for Judaism what Pope John XXIII has done for the Catholic Church." Despite their differences, Herzl and Buber respected each other and worked towards their goals.

In 1902, Buber became the editor of Die Welt, the main newspaper of the Zionist movement. But a year later, he became interested in the Jewish Hasidic movement. Buber admired how Hasidic communities truly lived their religion every day. Unlike the busy Zionist groups, who focused on politics, the Hasidim focused on values that Buber wanted Zionism to adopt. In 1904, he left most of his Zionist work to focus on studying and writing.

In the early 1920s, Martin Buber began to support a binational Jewish-Arab state. He believed Jewish people should declare their wish "to live in peace and brotherhood with the Arab people." He wanted them to build a shared homeland where both groups could develop freely.

Buber did not see Zionism as just another national movement. He wanted to create an ideal society. He said this society should not be one where Jews controlled Arabs. He felt it was important for the Zionist movement to agree with the Arabs, even if it meant Jews remained a minority. In 1925, he helped create an organization called Brit Shalom (Covenant of Peace). This group supported a binational state. For the rest of his life, he hoped Jews and Arabs would live together in peace in one nation. In 1942, he helped start the Ihud party, which also supported a binational plan. He remained friends with many Zionists and philosophers, including Chaim Weizmann and Max Brod.

After Israel was created in 1948, Buber wanted Israel to join a larger group of "Near East" states, not just Palestine.

Martin Buber's Career in Writing and Teaching

From 1905, Buber worked for a publishing company called Rütten & Loening. He helped create and oversee a series of books on social psychology.

From 1906 to 1914, Buber published collections of Hasidic, mystical, and mythical stories from Jewish and other cultures. In 1916, he moved from Berlin to Heppenheim.

During World War I, he helped create the Jewish National Committee. This group worked to improve the lives of Jews in Eastern Europe. During this time, he also became the editor of Der Jude (German for "The Jew"), a Jewish monthly magazine, which he edited until 1924. In 1921, Buber began a close friendship with Franz Rosenzweig. In 1922, they worked together at Rosenzweig's House of Jewish Learning, known as Lehrhaus.

In 1923, Buber wrote his famous book on existence, Ich und Du. He later edited the work but did not make big changes. In 1925, he started translating the Hebrew Bible into German with Franz Rosenzweig. He called this translation Verdeutschung ("Germanification"). This was because it didn't always use standard German. Instead, it tried to find new ways to express the many meanings of the original Hebrew. From 1926 to 1930, Buber helped edit a quarterly magazine called Die Kreatur ("The Creature").

In 1930, Buber became an honorary professor at the University of Frankfurt am Main. He resigned in protest when Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933. On October 4, 1933, the Nazi government stopped him from lecturing. In 1935, he was removed from the National Socialist authors' association. He then founded the Central Office for Jewish Adult Education. This became very important as the German government prevented Jews from public education. The Nazi government made it harder and harder for this office to operate.

Finally, in 1938, Buber left Germany and settled in Jerusalem, then the capital of Mandatory Palestine. He became a professor at Hebrew University. He taught about people and societies. His lectures from his first semester were published in the book The problem of man. In these lectures, he talked about how the question "What is Man?" became central to understanding people. He took part in discussions about the problems of Jews in Palestine and the Arab question. He used his knowledge of the Bible, philosophy, and Hasidism to do this.

He joined the group Ihud. This group wanted a bi-national state for Arabs and Jews in Palestine. Buber saw such a state as a better way to fulfill Zionism than a Jewish state alone. In 1949, he published Paths in Utopia. In this book, he explained his ideas about a communitarian socialist society. He described his theory of the "dialogical community," which is built on "dialogical relationships" between people.

After World War II, Buber started giving lectures in Europe and the United States. In 1952, he had a discussion with Carl Jung about whether God exists.

Martin Buber's Philosophy

Buber is famous for his idea of "dialogical existence," which he explained in his book I and Thou. However, his work covered many topics. These included religious awareness, modern life, the idea of evil, ethics, education, and how to understand the Bible.

Buber did not like being called a "philosopher" or "theologian." He said he was not interested in ideas, but only in personal experiences. He also said he could not talk about God, but only about relationships with God.

Politically, Buber's ideas about society are similar to some parts of anarchism. However, Buber himself said he was not an anarchist. He believed a state could exist under certain conditions.

Dialogue and Existence

In I and Thou, Buber shared his main idea about human existence. He believed that existence is about "encountering" others. He used two pairs of words, Ich-Du and Ich-Es, to describe how people think, interact, and exist with others, objects, and everything around them. In religious terms, he linked Ich-Du to Jesus and Ich-Es to Paul. These word pairs explain deep ideas about how a person lives and makes their life real. Buber said that a person is always relating to the world in one of these two ways.

Buber used the idea of dialogue (Ich-Du) and monologue (Ich-Es) to explain these two ways of being. Communication, especially talking, helps describe these ideas. It also shows how people connect with each other.

Ich-Du (I–Thou)

Ich-Du ("I–Thou" or "I–You") describes a relationship where two beings truly meet each other. It's a real and direct meeting. In this connection, they see each other as whole beings, without judging or treating the other as an object. Even thoughts and ideas don't play a role here. In an I–Thou meeting, endlessness and wholeness become real, not just ideas. Buber said that an Ich-Du relationship has no structure and shares no information. Even though you can't prove it happens (like measuring it), Buber said it is real and you can feel it. He gave examples like two lovers, a person and a cat, a writer and a tree, or two strangers on a train. Words like "encounter," "meeting," "dialogue," and "mutuality" describe this relationship.

One very important Ich-Du relationship Buber talked about was between a human being and God. Buber believed this is the only way to truly connect with God. He also said that an Ich-Du relationship with anything or anyone somehow connects to this eternal relationship with God.

To have this I–Thou relationship with God, a person needs to be open to it. But they shouldn't actively try to force it. Trying to force it would make it an "It" relationship, which prevents the true "I–Thou" connection. Buber said that if we are open, God will come to us. Also, because Buber described God as having no specific qualities, this I–Thou relationship lasts as long as the person wants it to. When a person goes back to relating in an "I–It" way, it stops the deeper connection and community.

Ich-Es (I–It)

The Ich-Es ("I–It") relationship is almost the opposite of Ich-Du. In Ich-Du, two beings truly meet. But in an Ich-Es relationship, the beings don't really meet. Instead, the "I" thinks about the other being as an idea or a concept. It treats that being like an object. All such objects are seen as just mental pictures, created and kept by the person's mind. This is partly based on Kant's idea that these objects exist only as thoughts in our minds. So, the Ich-Es relationship is actually a relationship with oneself. It's not a dialogue, but a monologue.

In the Ich-Es relationship, a person treats other things or people as objects to be used or experienced. This way of seeing things focuses on how an object can serve the person's own interests.

Buber believed that human life moves back and forth between Ich-Du and Ich-Es. He also thought that true Ich-Du experiences are quite rare. He felt that many problems in modernity (like feeling alone or being treated like a machine) came from people focusing too much on Ich-Es relationships. This even happened between people. Buber argued that this way of thinking made everything less valuable, including the meaning of life itself.

Hasidism and Mysticism

Buber was a scholar who studied, explained, and translated Hasidic stories. He saw Hasidism as a way to bring new life to Jewish culture. He often used examples from Hasidic traditions that highlighted community, relationships between people, and finding meaning in everyday activities. For Buber, the Hasidic ideal was to live life always feeling God's presence. There was no clear line between daily habits and religious experiences. This idea greatly influenced Buber's philosophy about human existence, which he saw as based on dialogue.

In 1906, Buber published Die Geschichten des Rabbi Nachman. This was a collection of tales by Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, a famous Hasidic leader. Buber retold these stories in his own Neo-Hasidic style. Two years later, Buber published Die Legende des Baalschem, which contained stories about the Baal Shem Tov, who founded Hasidism.

However, some people, like Chaim Potok, criticized Buber's interpretation of Hasidism. Potok said that Buber made Hasidism seem too perfect. He claimed Buber ignored its "charlatanism, obscurantism, internecine quarrels, its heavy freight of folk superstition and pietistic excesses, its tzadik worship, its vulgarized and attenuated reading of Lurianic Kabbalah". A stronger criticism was that Buber did not emphasize enough the importance of Jewish Law in Hasidism.

Awards and Recognition

- In 1951, Buber received the Goethe award from the University of Hamburg.

- In 1953, he received the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade.

- In 1958, he was given the Israel Prize in the humanities.

- In 1961, he was awarded the Bialik Prize for Jewish thought.

- In 1963, he won the Erasmus Prize in Amsterdam.

Published Works

In English

- 1937, I and Thou, transl. by Ronald Gregor Smith, Edinburgh: T. and T. Clark. 2nd Edition New York: Scribners, 1958. 1st Scribner Classics ed. New York, NY: Scribner, 2000, c1986

- 1952, Eclipse of God, New York: Harper and Bros. 2nd Edition Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1977.

- 1957, Pointing the Way, transl. Maurice Friedman, New York: Harper, 1957, 2nd Edition New York: Schocken, 1974.

- 1960, The Origin and Meaning of Hasidism, transl. M. Friedman, New York: Horizon Press.

- 1964, Daniel: Dialogues on Realization, New York, Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- 1965, The Knowledge of Man, transl. Ronald Gregor Smith and Maurice Friedman, New York: Harper & Row. 2nd Edition New York, 1966.

- 1966, The Way of Response: Martin Buber; Selections from his Writings, edited by N. N. Glatzer. New York: Schocken Books.

- 1967a, A Believing Humanism: My Testament, translation of Nachlese (Heidelberg 1965) by M. Friedman, New York: Simon and Schuster.

- 1967b, On Judaism, edited by Nahum Glatzer and transl. by Eva Jospe and others, New York: Schocken Books.

- 1968, On the Bible: Eighteen Studies, edited by Nahum Glatzer, New York: Schocken Books.

- 1970a, I and Thou, a new translation with a prologue “I and you” and notes by Walter Kaufmann, New York: Scribner’s Sons.

- 1970b, Mamre: Essays in Religion, translated by Greta Hort, Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.

- 1970c, Martin Buber and the Theater, Including Martin Buber’s “Mystery Play” Elijah, edited and translated with three introductory essays by Maurice Friedman, New York, Funk &Wagnalls.

- 1972, Encounter: Autobiographical Fragments. La Salle, Ill.: Open Court.

- 1973a, On Zion: the History of an Idea, with a new foreword by Nahum N. Glatzer, Translated from the German by Stanley Godman, New York: Schocken Books.

- 1973b, Meetings, edited with an introduction and bibliography by Maurice Friedman, La Salle, Ill.: Open Court Pub. Co. 3rd ed. London, New York: Routledge, 2002.

- 1983, A Land of Two Peoples: Martin Buber on Jews and Arabs, edited with commentary by Paul R. Mendes-Flohr, New York: Oxford University Press. 2nd Edition Gloucester, Mass.: *Peter Smith, 1994

- 1985, Ecstatic Confessions, edited by Paul Mendes-Flohr, translated by Esther Cameron, San Francisco: Harper & Row.

- 1991a, Chinese Tales: Zhuangzi, Sayings and Parables and Chinese Ghost and Love stories, translated by Alex Page, with an introduction by Irene Eber, Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press International.

- 1991b, Tales of the Hasidim, foreword by Chaim Potok, New York: Schocken Books, distributed by Pantheon.

- 1992, On Intersubjectivity and Cultural Creativity, edited and with an introduction by S.N. Eisenstadt, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- 1994, Scripture and Translation, Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig, translated by Lawrence Rosenwald with Everett Fox. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- 1996, Paths in Utopia, translated by R.F. Hull. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

- 1999a, The First Buber: Youthful Zionist Writings of Martin Buber, edited and translated from the German by Gilya G. Schmidt, Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press.

- 1999b, Martin Buber on Psychology and Psychotherapy: Essays, Letters, and Dialogue, edited by Judith Buber Agassi, with a foreword by Paul Roazin, New York: Syracuse University Press.

- 1999c, Gog and Magog: A Novel, translated from the German by Ludwig Lewisohn, Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

- 2002a, The Legend of the Baal-Shem, translated by Maurice Friedman, London: Routledge.

- 2002b, Between Man and Man, translated by Ronald Gregor-Smith, with an introduction by Maurice Friedman, London, New York: Routledge.

- 2002c, The Way of Man: According to the Teaching of Hasidim, London: Routledge.

- 2002d, The Martin Buber Reader: Essential Writings, edited by Asher D. Biemann, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- 2002e, Ten Rungs: Collected Hasidic Sayings, translated by Olga Marx, London: Routledge.

- 2003, Two Types of Faith, translated by Norman P. Goldhawk with an afterword by David Flusser, Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press.

Original writings (German)

- Die Geschichten des Rabbi Nachman (1906)

- Die fünfzigste Pforte (1907)

- Die Legende des Baalschem (1908)

- Ekstatische Konfessionen (1909)

- Chinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichten (1911)

- Daniel – Gespräche von der Verwirklichung (1913)

- Die jüdische Bewegung – gesammelte Aufsätze und Ansprachen 1900–1915 (1916)

- Vom Geist des Judentums – Reden und Geleitworte (1916)

- Die Rede, die Lehre und das Lied – drei Beispiele (1917)

- Ereignisse und Begegnungen (1917)

- Der grosse Maggid und seine Nachfolge (1922)

- Reden über das Judentum (1923)

- Ich und Du (1923)

- Translation: I and Thou by Walter Kaufmann (Touchstone: 1970)

- Das Verborgene Licht (1924)

- Die chassidischen Bücher (1928)

- Aus unbekannten Schriften (1928)

- Zwiesprache (1932)

- Kampf um Israel – Reden und Schriften 1921–1932 (1933)

- Hundert chassidische Geschichten (1933)

- Die Troestung Israels : aus Jeschajahu, Kapitel 40 bis 55 (1933); with Franz Rosenzweig

- Erzählungen von Engeln, Geistern und Dämonen (1934)

- Das Buch der Preisungen (1935); with Franz Rosenzweig

- Deutung des Chassidismus – drei Versuche (1935)

- Die Josefslegende in aquarellierten Zeichnungen eines unbekannten russischen Juden der Biedermeierzeit (1935)

- Die Schrift und ihre Verdeutschung (1936); with Franz Rosenzweig

- Aus Tiefen rufe ich Dich – dreiundzwanzig Psalmen in der Urschrift (1936)

- Das Kommende : Untersuchungen zur Entstehungsgeschichte des Messianischen Glaubens – 1. Königtum Gottes (1936 ?)

- Die Stunde und die Erkenntnis – Reden und Aufsätze 1933–1935 (1936)

- Zion als Ziel und als Aufgabe – Gedanken aus drei Jahrzehnten – mit einer Rede über Nationalismus als Anhang (1936)

- Worte an die Jugend (1938)

- Moseh (1945)

- Dialogisches Leben – gesammelte philosophische und pädagogische Schriften (1947)

- Der Weg des Menschen : nach der chassidischen Lehre (1948)

- Das Problem des Menschen (1948, Hebrew text 1942)

- Die Erzählungen der Chassidim (1949)

- Gog und Magog – eine Chronik (1949, Hebrew text 1943)

- Israel und Palästina – zur Geschichte einer Idee (1950, Hebrew text 1944)

- Der Glaube der Propheten (1950)

- Pfade in Utopia (1950)

- Zwei Glaubensweisen (1950)

- Urdistanz und Beziehung (1951)

- Der utopische Sozialismus (1952)

- Bilder von Gut und Böse (1952)

- Die Chassidische Botschaft (1952)

- Recht und Unrecht – Deutung einiger Psalmen (1952)

- An der Wende – Reden über das Judentum (1952)

- Zwischen Gesellschaft und Staat (1952)

- Das echte Gespräch und die Möglichkeiten des Friedens (1953)

- Einsichten : aus den Schriften gesammelt (1953)

- Reden über Erziehung (1953)

- Gottesfinsternis – Betrachtungen zur Beziehung zwischen Religion und Philosophie (1953)

- Translation Eclipse of God: Studies in the Relation Between Religion and Philosophy (Harper and Row: 1952)

- Hinweise – gesammelte Essays (1953)

- Die fünf Bücher der Weisung – Zu einer neuen Verdeutschung der Schrift (1954); with Franz Rosenzweig

- Die Schriften über das dialogische Prinzip (Ich und Du, Zwiesprache, Die Frage an den Einzelnen, Elemente des Zwischenmenschlichen) (1954)

- Sehertum – Anfang und Ausgang (1955)

- Der Mensch und sein Gebild (1955)

- Schuld und Schuldgefühle (1958)

- Begegnung – autobiographische Fragmente (1960)

- Logos : zwei Reden (1962)

- Nachlese (1965)

Chinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichten included the first German translation ever made of Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio. Alex Page translated the Chinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichten as "Chinese Tales", published in 1991 by Humanities Press.

Collected works

Werke 3 volumes (1962–1964)

- I Schriften zur Philosophie (1962)

- II Schriften zur Bibel (1964)

- III Schriften zum Chassidismus (1963)

Martin Buber Werkausgabe (MBW). Berliner Akademie der Wissenschaften / Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, ed. Paul Mendes-Flohr & Peter Schäfer with Martina Urban; 21 volumes planned (2001–)

Correspondence

Briefwechsel aus sieben Jahrzehnten 1897–1965 (1972–1975)

- I : 1897–1918 (1972)

- II : 1918–1938 (1973)

- III : 1938–1965 (1975)

Several of his original writings, including his personal archives, are preserved in the National Library of Israel, formerly the Jewish National and University Library, located on the campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

See also

In Spanish: Martin Buber para niños

In Spanish: Martin Buber para niños

- Existential therapy

- Guilt

- Humanistic psychology

- Intersubjectivity

- Contextual therapy

- André Neher

- List of Israel Prize recipients

- List of Bialik Prize recipients

- Jewish existentialism

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |