Theodor Herzl facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Theodor Herzl

|

|

|---|---|

| תֵּאוֹדוֹר הֶרְצְל | |

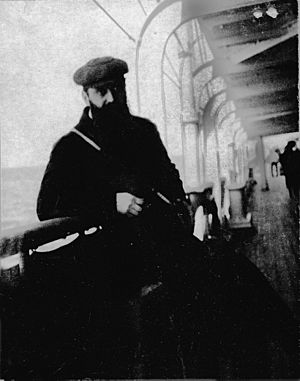

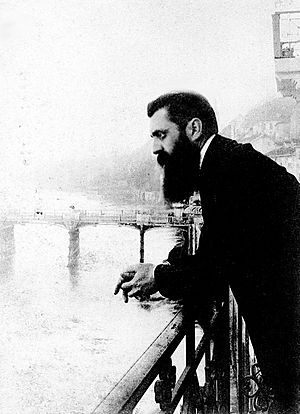

Herzl in 1897

|

|

| Born | 2 May 1860 |

| Died | 3 July 1904 (aged 44) Reichenau an der Rax, Austria-Hungary

|

| Resting place | 1904–1949: Döbling Cemetery, Vienna 1949–present: Mt. Herzl, Jerusalem |

| Other names | Binyamin Ze'ev |

| Citizenship | Hungarian |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Father of modern political Zionism |

| Spouse(s) |

Julie Naschauer

(m. 1889–1904) |

| Signature | |

Theodor Herzl (May 2, 1860 – July 3, 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, and writer. He is known as the founder of modern political Zionism. Herzl created the Zionist Organization. He worked to encourage Jewish people to move to Palestine to create a Jewish state.

Even though he died before Israel was formed, he is called "Chozeh HaMedinah" in Hebrew. This means "Visionary of the State." He is mentioned in Israel's Declaration of Independence. He is seen as the "spiritual father of the Jewish State." This means he gave a clear plan for political Zionism. However, he was not the first to have Zionist ideas. Many religious scholars had similar thoughts before him.

Contents

Early Life and Education

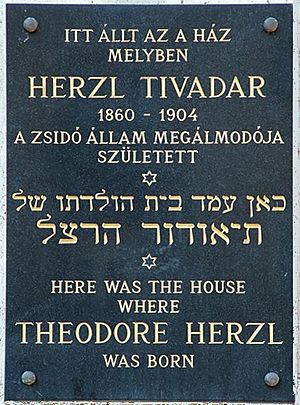

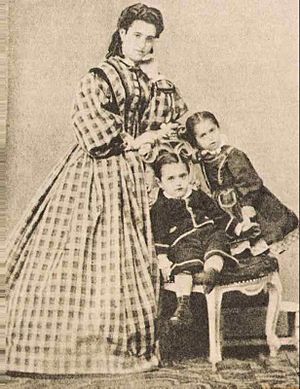

Theodor Herzl was born in Pest, Hungary (now part of Budapest). His family was Neolog Jewish, meaning they followed a modern form of Judaism. They spoke German and had blended into society. His father, Jakob Herzl, was a successful businessman. Theodor had an older sister named Pauline, who died in 1878.

As a young boy, Herzl wanted to be like Ferdinand de Lesseps, who built the Suez Canal. He was interested in science but later found a love for poetry and writing. This led him to a career in journalism. He also wrote plays. Herzl admired German culture. He believed that reading great books could help people become better. He thought this could help Hungarian Jews become more "civilized."

In 1878, after his sister's death, his family moved to Vienna, Austria. Herzl studied law at the University of Vienna. He joined a German student group called Albia. But he left the group because of their antisemitism, which is prejudice against Jewish people.

After a short time working in law, he became a journalist and writer. He worked for a Viennese newspaper and reported from Paris. He also traveled to London and Istanbul for his work. Later, he became a literary editor. His early writings were mostly descriptions, not about politics or Jewish life.

Becoming a Zionist Leader

As a reporter in Paris, Herzl followed the Dreyfus affair. This was a big political scandal in France. A Jewish French army captain was wrongly accused of spying. Herzl saw large protests in Paris during the trial. He said this event made him a Zionist. He was especially upset by crowds shouting "Death to the Jews!"

Some historians now think the Dreyfus affair might not have been the only reason for his change. They believe the rise of an antisemitic politician, Karl Lueger, in Vienna in 1895 had a bigger impact. Around this time, Herzl wrote a play called "The New Ghetto." It showed how Jewish people in Vienna, even those who were successful, still faced prejudice.

Herzl began to believe that antisemitism could not be stopped. He thought the only way for Jewish people to be safe was to have their own state. In 1895, he wrote in his diary that fighting antisemitism was "empty and useless." His newspaper editors did not want to publish his Zionist ideas.

Around this time, Herzl started writing about "A Jewish State." He believed these writings led to the start of the Zionist Movement. They certainly helped the movement grow.

The Jewish State Book

In late 1895, Herzl wrote Der Judenstaat (The State of the Jews). It was published in February 1896 and became very popular. The book argued that Jewish people should leave Europe and move to Palestine, their ancient homeland. Herzl believed Jewish people had a shared identity but lacked their own country. He thought a Jewish state would protect them from antisemitism. It would also allow them to freely express their culture and practice their religion.

Herzl's ideas quickly spread among Jewish communities. They also gained international attention. People who already supported Zionism joined him. However, some Orthodox Jews and those who wanted to blend into non-Jewish society opposed his ideas.

Working for a Jewish Homeland

Herzl worked hard to promote his ideas. He gained many supporters, both Jewish and non-Jewish. He saw himself as a leader for the Jewish people. Herzl tried to get support from the Ottoman Empire, which controlled Palestine. He suggested that if Jewish people settled in Palestine, the Zionist movement could help improve the Sultan's image and finances.

In 1896, Herzl met Reverend William Hechler, a British minister. Hechler had read Herzl's book and helped him meet important leaders. Through Hechler, Herzl met Frederick I, Grand Duke of Baden, who was the uncle of German Emperor Wilhelm II. These meetings helped Herzl and Zionism gain more respect around the world. Herzl publicly met Wilhelm II in 1898.

In May 1896, the English version of Der Judenstaat was published as The Jewish State. Herzl admitted he wrote his ideas without knowing about earlier Zionist writings.

In Istanbul, Herzl tried to meet Sultan Abdulhamid II. He wanted to propose that Jewish people would help pay Turkey's foreign debt. In return, they would get Palestine as a Jewish homeland. He didn't meet the Sultan but spoke with other high-ranking officials. He received a medal, which showed the talks were serious. Five years later, in 1901, Herzl did meet the Sultan, but his offer was turned down.

After returning from Istanbul, Herzl went to London. He spoke to a large crowd of Jewish immigrants. They gave him their support to lead the Zionist movement. This helped the movement grow quickly.

Leading the Zionist Movement

In 1897, Herzl started the Zionist newspaper Die Welt in Vienna. He also organized the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland. He was chosen as the president of the Congress and held this role until his death. From 1898, he began to work with leaders from different countries to gain support for a Jewish country. He met with Wilhelm II several times, including in Jerusalem. He also attended the Hague Peace Conference and was well-received by many leaders there.

Herzl believed that Jewish people had no future in Europe because of antisemitism. He thought every European country had tried to force Jewish people to blend in, but it didn't work. He therefore called for a large movement of Jewish people out of Europe to a "Jewish State."

Visiting the Holy Land

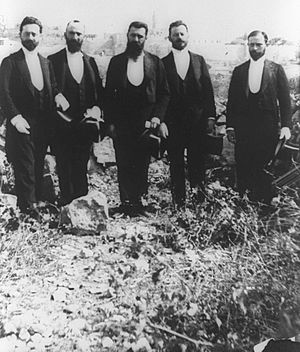

Herzl visited Jerusalem for the first time in October 1898. He planned his visit to happen at the same time as Wilhelm II's trip. He hoped this would bring public recognition to himself and Zionism. Herzl and Wilhelm II met publicly on October 29, 1898, near Holon, Israel. It was a short but important meeting. They had another meeting in Jerusalem on November 2, 1898.

In 1902–03, Herzl spoke before a British Royal Commission. This led him to work closely with the British government. He discussed a plan to settle Jews in Al 'Arish in the Sinai Peninsula, next to Palestine. However, this plan was stopped because it was not practical.

In 1903, Herzl tried to get support for a Jewish homeland from Pope Pius X. He suggested Palestine could be a safe place for Jews fleeing persecution in Russia. But the Pope said the Church could not support this idea as long as Jews did not accept the divinity of Christ.

Also in 1903, after a violent attack on Jews in Kishinev, Herzl visited St. Petersburg, Russia. He met with Russian ministers to discuss ways to improve the situation for Jews in Russia.

Around this time, Joseph Chamberlain, a British official, suggested a Jewish colony in what is now Kenya. This plan was called the "Uganda Project." Herzl presented it at the Sixth Zionist Congress in August 1903. Most delegates agreed to look into the offer. However, many, especially from Russia, strongly opposed it. In 1905, the 7th Zionist Congress decided to turn down the British offer. They firmly committed to establishing a Jewish homeland only in Palestine.

Death and Legacy

Herzl died on July 3, 1904, in Edlach, Austria. He had been diagnosed with a heart problem earlier that year and died of heart sclerosis. The day before he died, he told Reverend William H. Hechler, "Greet Palestine for me. I gave my heart's blood for my people."

His will asked for a simple funeral without speeches or flowers. He also asked to be buried next to his father until the Jewish people could take his remains to Israel. Despite his wishes, about six thousand people followed his coffin. The funeral was long and disorganized. A short speech was given by David Wolffsohn, and Herzl's son, Hans, read a prayer.

Herzl was first buried in Vienna. In 1949, his remains were brought to Israel and buried on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem, which was named after him. His coffin was covered with a blue and white cloth. It had a Star of David and a Lion of Judah, along with seven gold stars. These stars were a reminder of Herzl's original idea for the flag of the Jewish state.

Herzl Day is an Israeli national holiday. It is celebrated every year on the tenth day of the Hebrew month of Iyar. This day honors the life and vision of Theodor Herzl.

Herzl's Family Life

Herzl knew both of his grandfathers. They were more connected to traditional Judaism than his parents were. His grandfather, Simon Loeb Herzl, had read an early book about Jewish people returning to the Holy Land. Experts believe this connection influenced Herzl's ideas about modern Zionism.

On June 25, 1889, Herzl married Julie Naschauer. She was 21 and from a wealthy Jewish family in Vienna. Their marriage was not happy, but they had three children: Paulina, Hans, and Margaritha (Trude). Julie died in 1907, three years after Herzl.

Important Writings

In late 1895, Herzl wrote Der Judenstaat (The State of the Jews). This small book was published on February 14, 1896. Its subtitle was "Proposal of a modern solution for the Jewish question." Der Judenstaat explained the ideas and structure of political Zionism. Herzl's solution was to create a Jewish state. In the book, he explained why a historic Jewish state needed to be reestablished.

His last major work was Altneuland (meaning The Old New Land), a novel published in 1902. Herzl spent three years writing this book. It was not just a story but a serious look at what could be achieved in one generation. The main ideas were a love for Zion and the belief that changes could happen by combining the best efforts of all people.

Herzl imagined a Jewish state that mixed modern Jewish culture with the best parts of European culture. He thought a "Palace of Peace" would be built in Jerusalem to solve international problems. He also imagined the Temple being rebuilt using modern ideas. Herzl did not think the Jewish citizens would be very religious, but he believed religion would be respected publicly. He also thought many languages would be spoken, and Hebrew might not be the main one.

In Altneuland, Herzl did not see any conflict between Jews and Arabs. One character, Reshid Bey, an engineer from Haifa, is a leader in the "New Society." He is thankful to his Jewish neighbors for improving the economy. All non-Jews would have equal rights. A fanatical rabbi tries to take away the rights of non-Jewish citizens, but he fails in an election.

Herzl also imagined the future Jewish state as a "third way" between capitalism and socialism. It would have good welfare programs and public ownership of natural resources. Industry, farming, and trade would be organized cooperatively. Herzl called his economic model "Mutualism." Women would also have equal voting rights.

In Altneuland, Herzl showed his vision for a new Jewish state in the Land of Israel. The phrase "If you will it, it is no dream" from his book became a famous slogan for the Zionist movement. It meant that if people truly wanted something, it could happen.

In his novel, Herzl wrote about an election in the new state. He was against a nationalist party that wanted to make Jews a special class. Herzl believed Zionism meant being fair and tolerant to everyone. Altneuland was written for both Jews and non-Jews. Herzl wanted to gain support for Zionism from non-Jewish people.

The name "Tel Aviv" came from the Hebrew translation of Altneuland by Nahum Sokolow. This name means "hill of spring." This name was later given to the new city built outside Jaffa, which became Tel Aviv-Yafo, the second-largest city in Israel. The nearby city of Herzliya was named in honor of Herzl.

Published Works

Books

- The Jewish State (Der Judenstaat) (1896)

- The Old New Land (Altneuland) (1902)

- Hagenau (1881)

Plays

- Kompagniearbeit, comedy in one act, Vienna 1880

- Die Causa Hirschkorn, comedy in one act, Vienna 1882

- Tabarin, comedy in one act, Vienna 1884

- Muttersöhnchen, in four acts, Vienna 1885

- Seine Hoheit, comedy in three acts, Vienna 1885

- Der Flüchtling, comedy in one act, Vienna 1887

- Wilddiebe, comedy in four acts, in co-authorship with H. Wittmann, Vienna 1888

- Was wird man sagen?, comedy in four acts, Vienna 1890

- Die Dame in Schwarz, comedy in four acts, in co-authorship with H. Wittmann, Vienna 1890

- Prinzen aus Genieland, comedy in four acts, Vienna 1891

- Die Glosse, comedy in one act, Vienna 1895

- Das Neue Ghetto, drama in four acts, Vienna 1898. This was Herzl's only play with Jewish characters.

- Unser Kätchen, comedy in four acts, Vienna 1899

- Gretel, comedy in four acts, Vienna 1899

- I love you, comedy in one act, Vienna 1900

- Solon in Lydien, drama in three acts, Vienna 1905

Other Writings

- Herzl, Theodor. Theodor Herzl: Excerpts from His Diaries (2006)

- Herzl, Theodor. Philosophische Erzählungen Philosophical Stories (1900)

Images for kids

-

Grave of Herzl's grandfather Simon (1797–1879) in Zemun Cemetery, Belgrade.

-

Grave of Herzl's grandmother Rivka (1798–1888) in Zemun Cemetery, Belgrade.

-

Theodor Herzl's funeral in Vienna.

-

Honor guards stand beside Herzl's coffin on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem, 1949.

See also

In Spanish: Theodor Herzl para niños

In Spanish: Theodor Herzl para niños

- Gathering of Israel

- Herzl Day

- Jewish diaspora

- Return to Zion