Kingdom of Hungary (1526–1867) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Hungary

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1526–1867 | |||||||||||||

|

Motto: Regnum Mariae Patrona Hungariae

"Kingdom of Mary, the Patron of Hungary" |

|||||||||||||

|

Anthem: Himnusz

Hymn |

|||||||||||||

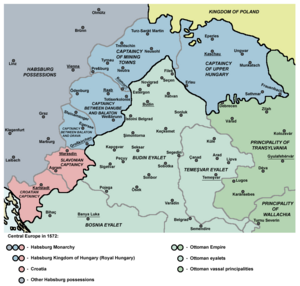

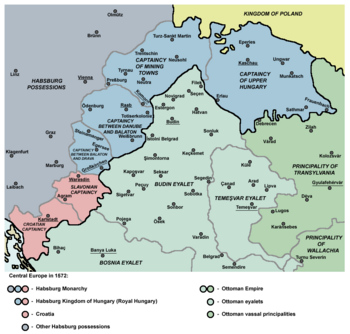

Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary (light blue) in personal union with the Kingdom of Croatia (red), both within the Habsburg monarchy (in shades of blue) in 1572.

|

|||||||||||||

| Status | Crownland of Habsburg monarchy and from 1804 the Austrian Empire In personal union with the Kingdom of Croatia (see historical context section) |

||||||||||||

| Capital | Buda (1526–1536, 1784–1873) Pressburg (1536–1783) |

||||||||||||

| Common languages | Official languages: Latin (before 1784; 1790–1844) German (1784–1790; 1849–1867) Hungarian (1836–1849) Other spoken languages: Romanian, Slovak, Croatian, Slovene, Serbian, Italian, Ruthenian |

||||||||||||

| Religion | Catholic, Reformed, Lutheranism, Orthodox, Unitarianism, Judaism | ||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Hungarian | ||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Apostolic King | |||||||||||||

|

• 1526–1564 (first)

|

Ferdinand I | ||||||||||||

|

• 1848–1867 (last)

|

Franz Joseph I | ||||||||||||

| Palatine | |||||||||||||

|

• 1526–1530 (first)

|

Stephen Báthory | ||||||||||||

|

• 1847–1848 (last)

|

Stephen Francis | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Royal Diet | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early Modern | ||||||||||||

| 29 August 1526 | |||||||||||||

|

• Treaty of Nagyvárad

|

24 February 1538 | ||||||||||||

|

• Siege of Eger

|

9 September – 17 October 1552 | ||||||||||||

| 1 August 1664 | |||||||||||||

|

• Wesselényi conspiracy

|

1664–1671 | ||||||||||||

| 26 January 1699 | |||||||||||||

| 1703–1711 | |||||||||||||

|

• Hungarian Reform Era

|

1825-1848 | ||||||||||||

|

• Hungarian Revolution

|

15 March 1848 | ||||||||||||

| 30 March 1867 | |||||||||||||

| Currency | Forint | ||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | HU | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Hungary was a country that existed between 1526 and 1867. It was not part of the Holy Roman Empire. Instead, it was a key part of the lands ruled by the Habsburg monarchy. This monarchy later became the Austrian Empire in 1804.

After the important Battle of Mohács in 1526, Hungary had two kings at the same time. These were John I and Ferdinand I. Both kings wanted to rule the entire kingdom. This led to a period of disagreement until 1570. In that year, John Sigismund Zápolya (John II) gave up his claim as King of Hungary. He did this in favor of Emperor Maximilian II.

At first, the areas ruled by the Habsburg kings were called "Kingdom of Hungary" or "Royal Hungary." Royal Hungary kept its old laws and traditions. It was a symbol that the country's legal system continued, even though the Ottoman Empire occupied parts of Hungary. However, it was mostly controlled by the Habsburgs. The Hungarian nobles worked hard to make Vienna, the Habsburg capital, agree that Hungary was special. They wanted it to be ruled by its own laws.

In 1699, the Great Turkish War ended with the Treaty of Karlowitz. This treaty meant the Ottomans gave back almost all of the lands they had taken in Hungary. These new areas joined the Kingdom of Hungary. The Diet of Hungary, a kind of parliament in Pressburg, then governed these lands.

Two major Hungarian uprisings happened during this time. These were Rákóczi's War of Independence in the early 1700s and the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. These events brought big changes to the country. In 1867, the kingdom became a "dual monarchy" with Austria. This new country was known as Austria-Hungary.

Contents

Royal Hungary: A Part of the Habsburg Lands (1526–1699)

"Royal Hungary" was the name for the part of Hungary where the Habsburgs were accepted as kings. This happened after the Ottoman victory at the Battle of Mohács in 1526. The country was then divided.

In 1538, the Treaty of Nagyvárad officially split the country between the two rival rulers. The Habsburgs got the northern and western parts, which became Royal Hungary. Their new capital was Pressburg (now Bratislava). John I kept the eastern part, known as the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom.

The Habsburg rulers needed Hungary's money to fight the Ottomans. During these wars, the size of the Kingdom of Hungary shrank by about 60 percent. Even though it was smaller and damaged by war, Royal Hungary was still very important. It was as vital to the Habsburgs as their lands in Austria or Bohemia.

Today's Slovakia and northwestern Transdanubia were part of Royal Hungary. Control of northeastern Hungary often changed between Royal Hungary and the Principality of Transylvania. The central areas of medieval Hungary were ruled by the Ottoman Empire for 150 years.

In 1570, John Sigismund Zápolya gave up his title as King of Hungary. He did this for Emperor Maximilian II, as agreed in the Treaty of Speyer. After 1699, people stopped using the term "Royal Hungary." The Habsburg kings then called the larger country simply the "Kingdom of Hungary."

Habsburg Kings and Hungarian Control

The Habsburgs were a powerful family from the Holy Roman Empire. They were chosen as Kings of Hungary. Royal Hungary became part of the Habsburg monarchy. However, it had little power in Vienna, the Habsburg capital.

The Habsburg king directly managed Hungary's money, army, and foreign relations. Imperial soldiers guarded its borders. The Habsburgs often left the position of palatine empty. This was to stop anyone from gaining too much power.

Hungarians and Habsburgs also disagreed about the Ottoman Empire. Vienna wanted peace with the Ottomans. Hungarians wanted them removed. Hungarians felt their position was weak. Many became unhappy with Habsburg rule. They complained about foreign soldiers and Vienna's deals with the Ottomans regarding Transylvania. Protestants in Royal Hungary felt the Counter-Reformation was a bigger threat than the Turks.

Hungary's economy was very important to the Habsburgs. Even with huge losses of land and people, Royal Hungary was a major source of income. It was as important as the Habsburgs' lands in Austria or Bohemia. In fact, it was the largest source of money for Ferdinand I.

The Reformation's Impact on Hungary

The Reformation spread quickly in Hungary. By the early 1600s, most noble families were no longer Catholic. In Royal Hungary, most people became Lutheran by the late 1500s.

Archbishop Péter Pázmány worked to rebuild the Roman Catholic Church in Royal Hungary. He led a Counter-Reformation. He used persuasion, not force, to win back Protestants. The Reformation caused divisions. Catholics often supported the Habsburgs. Protestants developed a strong national identity. This made them seem like rebels to the Austrians. There were also differences between the mostly Catholic powerful nobles and the mainly Protestant lesser nobles.

Kingdom of Hungary: Early Modern Period to 1848

Changes in the 18th Century

As the Habsburgs gained more control over former Turkish lands, some officials thought they should rule Hungary as a conquered area. But at a meeting in Pressburg in 1687, Emperor Leopold I promised to respect Hungary's laws and rights. However, the Habsburgs were recognized as the hereditary rulers. The nobles' right to resist the king was also removed.

In 1690, Leopold started giving away lands freed from the Turks. Protestant nobles and other Hungarians seen as disloyal lost their properties. These were given to foreigners. Vienna controlled Hungary's foreign affairs, defense, and taxes.

Hungarians were unhappy about the treatment of Protestants and the land seizures. In 1703, a peasant uprising began. This led to an eight-year rebellion against Habsburg rule. In Transylvania, which became part of Hungary again, people united under Francis II Rákóczi. Most of Hungary soon supported Rákóczi. The Hungarian Diet even voted to remove the Habsburgs from the throne.

However, the Habsburgs made peace in the west and focused their full power on Hungary. The war ended in 1711 with the Treaty of Szatmár. This treaty promised that the Diet would meet again in Pressburg. It also offered forgiveness for the rebels.

Leopold's successor, King Charles III (1711–40), worked to improve relations with Hungary. Charles asked the Diet to approve the Pragmatic Sanction. This document stated that the Habsburg ruler would govern Hungary as a king, following its constitution and laws. He hoped this would keep the Habsburg Empire together if his daughter, Maria Theresa, became ruler. The Diet approved it in 1723. Hungary agreed to be a hereditary monarchy under the Habsburgs.

In reality, Charles and later rulers governed almost like dictators. They controlled Hungary's foreign affairs, defense, and money. But they could not tax the nobles without their approval. Charles also created a standing army in 1715. This army was paid for by non-nobles. This meant nobles didn't have to serve in the military, but they also didn't pay taxes. Charles also made it harder to become Protestant.

Maria Theresa (1741–80) faced challenges when she became ruler. In 1741, she asked Hungary's nobles for support. They stood by her and helped her keep her rule. Maria Theresa later worked to strengthen ties with Hungarian nobles. She created schools to attract them to Vienna.

Under Charles and Maria Theresa, Hungary's economy struggled. Many years of Ottoman rule and war had greatly reduced Hungary's population. Large parts of the south were almost empty. There was a shortage of workers as landowners tried to rebuild their estates. The Habsburgs brought in many peasants from other parts of Europe. These included Slovaks, Serbs, Croatians, and Germans. Many Jews also moved from Vienna and Poland. Hungary's population more than tripled between 1720 and 1787, reaching 8 million. However, only 39 percent were Magyars (Hungarians).

In the early 1700s, Hungary's economy was mostly farming. About 90 percent of people worked in agriculture. Farmers did not use fertilizers, roads were bad, and rivers were blocked. Poor storage methods caused a lot of grain to be lost. People often traded goods instead of using money. There was little trade between towns and serfs (farm workers tied to the land).

After 1760, there were too many workers. The number of serfs grew, and their living standards dropped. Landowners started demanding more from new tenants. They also broke old agreements. In response, Maria Theresa issued her Urbarium in 1767. This protected serfs by giving them more freedom to move. It also limited the amount of forced labor they had to do. Despite her efforts, the situation worsened. Many serfs left their land between 1767 and 1848. Most became farmworkers without land. There were few jobs in towns because there wasn't much industry.

Joseph II (1780–90) was a strong leader. He was influenced by the Age of Enlightenment. He tried to centralize control of the empire. He wanted to rule as an "enlightened despot," making decisions by decree. He refused to take the Hungarian coronation oath. This was so he wouldn't be limited by Hungary's constitution.

In 1781–82, Joseph issued a Patent of Toleration. This gave Protestants and Orthodox Christians full civil rights. Jews also gained freedom of worship. He ordered that German replace Latin as the official language. He also gave peasants the freedom to leave their land, marry, and choose their jobs. Hungary, Slavonia, Croatia, the Military Frontier, and Transylvania became one area. It was called the Kingdom of Hungary or "Lands of the Crown of St. Stephen." When Hungarian nobles refused to give up their tax exemption, Joseph banned Hungarian goods from Austria. He also started a survey to prepare for a general land tax.

Joseph's changes angered Hungarian nobles and clergy. Peasants were unhappy with taxes and military service. Hungarians saw Joseph's language reform as German control. They reacted by demanding the right to use their own language. This led to a revival of Hungarian language and culture. The lesser nobles questioned the loyalty of the powerful magnates. Many magnates were not ethnic Hungarians. Even those who were spoke French and German.

This Hungarian national awakening also sparked similar movements among other groups in Hungary. These included Slovaks, Romanians, Serbs, and Croatians. They felt threatened by both German and Hungarian cultural dominance. These movements later grew into nationalist movements. They helped lead to the empire's eventual collapse.

Late in his rule, Joseph fought a costly and unsuccessful war against the Turks. This weakened his empire. On January 28, 1790, shortly before his death, he canceled most of his reforms. Only the Patent of Toleration, peasant reforms, and the end of religious orders remained.

Joseph's successor, Leopold II (1790–92), again treated Hungary as a separate country. In 1791, the Diet passed Law X. This law stated that Hungary was an independent kingdom. It could only be ruled by a king crowned according to Hungarian laws. Law X later became the basis for Hungarian demands for self-rule. New laws now needed approval from both the Habsburg king and the Diet. Latin became the official language again. However, peasant reforms stayed in place, and Protestants remained equal before the law. Leopold died in March 1792. This was just as the French Revolution was becoming more extreme.

Hungary in the Early 1800s

The idea of "enlightened absolutism" ended in Hungary under Leopold's successor, Francis II (ruled 1792–1835). He strongly disliked change, which led to decades of no political progress in Hungary. In 1795, Hungarian police arrested Ignác Martinovics and other thinkers. They were accused of planning a revolution to create a democratic system in Hungary. After this, Francis decided to stop any ideas for reform. The execution of these people silenced reformers among the nobles. For about 30 years, reform ideas were only found in poetry and philosophy. The powerful nobles also feared a popular uprising. They became tools of the crown and put more burdens on the peasants.

In 1804, Francis II, who was also the Holy Roman Emperor, created the Austrian Empire. Hungary and all his other lands became part of it. This created a formal structure for the Habsburg Monarchy. It had been a collection of different lands for about 300 years. Francis became Francis I, the first Emperor of Austria. He ruled from 1804 to 1835. He was the only "double emperor" in history. The way the empire worked and the status of its parts stayed much the same. Hungary's affairs continued to be managed by its own institutions, like the King and the Diet. Hungary was still seen as a separate kingdom.

By the early 1800s, Hungarian farmers changed how they worked. They moved from growing food for themselves to producing large amounts for sale. Better roads and waterways lowered transport costs. Cities in Austria and Bohemia grew. The need for supplies during the Napoleonic Wars also increased demand for food and clothes. Hungary became a major exporter of grain and wool. New lands were cleared, and farming methods improved.

However, Hungary did not get the full benefits of this boom. Most of the profits went to the powerful nobles. They spent the money on luxuries instead of investing it. As expectations rose, items like linen and silverware became necessities. Wealthy nobles managed their money well. But many lesser nobles went into debt to keep up their social status.

Napoleon's final defeat led to an economic slowdown. Grain prices fell as demand dropped. Many lesser nobles were caught in debt. Poverty forced many of them to work for a living. Their sons went to school to become civil servants or professionals. The decline of the lesser nobility continued. By 1820, Hungary's exports were higher than during the war. But as more lesser nobles got diplomas, there were not enough jobs. This left many unhappy graduates. These new educated people became interested in new political ideas from Western Europe. They organized to change Hungary's political system.

Francis rarely called the Diet to meet. He usually only did so to ask for soldiers and supplies for war. But he always heard complaints. Economic problems made the lesser nobles very unhappy by 1825. Francis finally called the Diet after 14 years. People voiced their complaints and called for reforms. They demanded less royal interference and more use of the Hungarian language.

The first great leader of the reform era appeared in 1825. Count István Széchenyi was a powerful noble. He surprised the Diet by giving the first speech in Hungarian ever heard in the upper house. He also promised a year's income to support a Hungarian academy of arts and sciences. In 1831, angry nobles burned Szechenyi's book, Hitel (Credit). In it, he argued that the nobles' special rights were wrong and hurt their own finances. Szechenyi called for an economic revolution. He believed only the powerful nobles could make these changes. Szechenyi wanted a strong connection with the Habsburg Empire. He called for ending old land laws and serfdom. He also wanted landowners to pay taxes, foreign money for development, a national bank, and paid labor. He inspired projects like the Széchenyi Chain Bridge connecting Buda and Pest. Szechenyi's reforms ultimately failed. They were aimed at the powerful nobles, who didn't want change. Also, his program was too slow to attract the unhappy lesser nobles.

Lajos Kossuth was the most popular reform leader in Hungary. He made passionate calls for change to the lesser nobles. Kossuth was the son of a lesser nobleman who had no land. He became a lawyer. He then moved to Pest. There, he wrote about the Diet's activities. This made him popular with young people who wanted reform. Kossuth was jailed in 1836 for treason. After his release in 1840, he became famous as the editor of a liberal newspaper.

Kossuth argued that Hungary's problems would only improve if it separated from Austria. He called for more democracy in parliament, fast industrial growth, general taxation, economic growth through exports, and an end to special rights (equality before the law) and serfdom. But Kossuth was also a strong Hungarian patriot. His speeches angered Hungary's minority ethnic groups. Kossuth gained support among liberal lesser nobles. They formed an opposition group in the Diet. They pushed for reforms with growing success after Francis's death in 1835. Ferdinand V (1835–48) then became ruler. In 1844, a law was passed making Hungarian the country's only official language.

-

István Széchenyi, a key figure of the reform era.

-

Lajos Kossuth, a popular leader of Hungarian reform.

Hungary After the 1848 Revolution (1848–1867)

After the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, the emperor took away Hungary's constitution. He took complete control. Emperor Franz Joseph divided the country into four areas: Hungary, Transylvania, Croatia-Slavonia, and Vojvodina. German and Bohemian officials ran the government. German became the language for government and higher education. The non-Magyar groups in Hungary received little for helping Austria during the unrest. A Croat reportedly told a Hungarian, "We received as a reward what the Magyars got as a punishment."

Hungarian public opinion was divided on relations with Austria. Some Hungarians hoped for complete separation from Austria. Others wanted to find a way to work with the Habsburgs. But they wanted the Habsburgs to respect Hungary's constitution and laws. Ferenc Deák became the main supporter of working together. Deak argued that the April laws were legal. He said that any changes to them needed the Hungarian Diet's approval. He also believed that removing the Habsburgs from the throne was not valid. Deak argued that as long as Austria ruled completely, Hungarians should only resist unfair demands without violence.

The first sign of weakness in Franz Joseph's absolute rule came in 1859. The armies of Sardinia-Piedmont and France defeated Austria at the Battle of Solferino. This defeat convinced Franz Joseph that opposition to his government was too strong to manage alone. He slowly realized he needed to make agreements with Hungary. Austria and Hungary then began to work towards a compromise.

In 1866, the Prussians defeated the Austrians in the Austro-Prussian War. This showed even more how weak the Habsburg Empire was. Talks between the emperor and Hungarian leaders became more intense. They finally led to the Compromise of 1867. This agreement created the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary, also known as the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Population of the Kingdom of Hungary

| Ethnic groups of the Kingdom of Hungary according to Hungarian statistician Elek Fényes | Number c. 1840 |

Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Magyars (including Gypsies (75,107) because they speak Hungarian) | 4,812,759 | 37.36 % |

| Slavs (Slovaks, Rusyns, Bulgarians, Serbs, Croats, etc.) | 4,330,165 | 33.62 % |

| Vlachs | 2,202,542 | 17.1 % |

| Germans (Transylvanian Saxons, Danube Swabians, etc.) | 1,273,677 | 9.89 % |

| Jews | 244,035 | 1.89 % |

| French (mostly from Lorraine and Alsace) | 6,150 | 0.05 % |

| Greeks | 5,680 | 0.04 % |

| Armenians | 3,798 | 0.03 % |

| Albanians | 1,600 | 0.01 % |

| Total | 12,880,406 | 100 % |

See also

- List of Hungarian rulers